Imagine a Brachiosaurus munching on towering trees, or a Triceratops grazing on prehistoric shrubs. Without teeth designed for grinding, how did these magnificent creatures process such tough plant material? The answer lies in an ingenious digestive adaptation: the deliberate consumption of stones. This practice, known as lithophagy or, more specifically, gastrolith usage, played a crucial role in dinosaur digestion. These swallowed stones functioned essentially as nature’s food processor, compensating for dental limitations and enabling dinosaurs to extract maximum nutrition from their diets. Let’s explore this fascinating digestive strategy that helped dinosaurs thrive for over 165 million years.

The Gastrolith Phenomenon

Gastroliths, derived from the Greek words for “stomach stones,” were rocks intentionally swallowed by certain dinosaur species to aid in digestion. These stones resided in the gizzard, a specialized muscular stomach that used mechanical grinding action rather than chemical processing. When a dinosaur consumed plant material, the gizzard would contract and churn, causing the stones to pulverize the food into smaller, more digestible particles. This mechanical breakdown was essential for herbivorous dinosaurs, whose plant-based diets consisted of tough, fibrous vegetation that required significant processing before nutrients could be extracted. The gastrolith system represents one of nature’s most elegant solutions to the challenge of processing difficult-to-digest food without specialized dentition.

Which Dinosaurs Used Gastroliths?

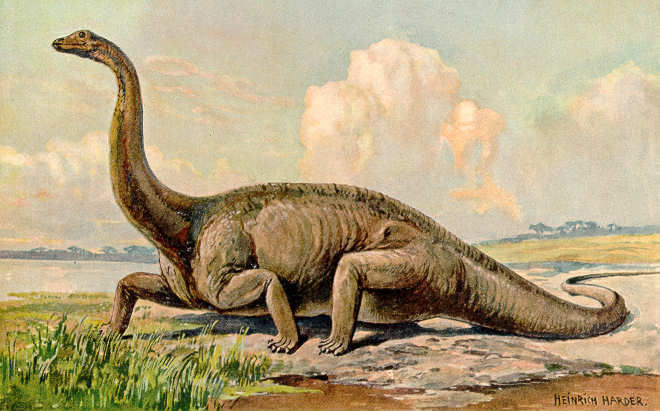

Not all dinosaurs employed gastroliths in their digestive strategy, as this adaptation was primarily found among certain herbivorous groups. Sauropods, the long-necked giants like Diplodocus and Apatosaurus, are perhaps the most famous gastrolith users, with some specimens found with collections of polished stones in their abdominal regions. Ornithopods such as Iguanodon and hadrosaurs (“duck-billed” dinosaurs) also likely utilized this digestive method. Interestingly, many theropods (predominantly carnivorous dinosaurs) generally did not need gastroliths, as their diet of meat was more easily broken down through chemical digestion and with their sharp, serrated teeth. The distribution of gastrolith usage across dinosaur groups provides valuable insights into their varied dietary specializations and evolutionary adaptations.

The Science Behind Dinosaur Gizzards

The dinosaur gizzard functioned as a remarkable evolutionary adaptation that compensated for the lack of grinding molars in many herbivorous species. Located between the esophagus and the true stomach, this muscular pouch contained the gastroliths and performed the mechanical breakdown of food. The walls of the gizzard contained powerful muscles that could contract with surprising force, moving the stones against each other and food particles. Modern birds, the direct descendants of theropod dinosaurs, maintain this adaptation today, offering scientists a living model for understanding dinosaur digestion. Research suggests that dinosaur gizzards may have been even more powerful than those of modern birds, capable of generating tremendous grinding force to process the coarse vegetation of the Mesozoic era.

How Paleontologists Identify Gastroliths

Identifying true gastroliths in the fossil record requires careful scientific analysis, as not every stone found near dinosaur remains was necessarily ingested. Authentic gastroliths typically exhibit distinctive characteristics that separate them from surrounding rocks. The most telling sign is a high degree of polish or smoothness, created by the continuous grinding action within the gizzard. Genuine gastroliths often have rounded edges and may show distinctive wear patterns or striations from repeatedly contacting other stones. Additionally, the composition of the stones frequently differs from the local geology where the dinosaur was fossilized, indicating deliberate selection rather than accidental inclusion. Paleontologists must conduct thorough taphonomic studies to confirm that stones were actually within the dinosaur’s digestive tract rather than coincidentally positioned near the skeleton during fossilization.

The Selective Process of Stone Consumption

Dinosaurs didn’t arbitrarily consume any rocks they encountered; evidence suggests they were surprisingly selective in their gastrolith choices. Studies of preserved gastrolith collections indicate preferences for certain stone types, particularly those with greater hardness and durability. Quartz, quartzite, and various crystalline rocks appear frequently among identified gastroliths, likely chosen for their resistance to breakdown and their effective grinding properties. The selection process might have involved visual identification, testing rocks with their mouths, or possibly learning from observation of other herd members. Some paleontologists theorize that dinosaurs may have traveled considerable distances to access suitable gastrolith material, potentially returning to specific “gastrolith quarries” as part of their migratory patterns. This selective behavior represents a remarkable level of specialized feeding adaptation that helped dinosaurs optimize their digestive efficiency.

Size and Quantity of Dinosaur Gastroliths

The size and number of gastroliths varied considerably across different dinosaur species, generally scaling with the animal’s body size. Massive sauropods could carry impressive quantities of stones, with some specimens containing several hundred individual gastroliths weighing collectively up to 30 pounds. The individual stones typically ranged from pebble-sized to occasionally as large as a human fist. Smaller dinosaur species naturally maintained proportionally smaller gastrolith collections. The quantity needed was directly related to the coarseness of the dinosaur’s diet and the efficiency of its digestive system. Fascinating research suggests that dinosaurs may have regularly replenished their gastrolith supply, replacing stones that had become too smooth or too small through the grinding process. The management of this internal “tool kit” represents a sophisticated level of physiological self-regulation.

Comparing Dinosaur Gastroliths to Modern Animals

The practice of swallowing stones for digestive purposes is not unique to dinosaurs but continues in many modern animals, providing valuable comparative models for paleontologists. Contemporary birds, as dinosaur descendants, most clearly demonstrate this connection – chickens, turkeys, and ostriches all utilize gizzard stones. Crocodilians, the closest living relatives to dinosaurs and birds, also occasionally ingest gastroliths, though for somewhat different purposes, including buoyancy regulation. Certain herbivorous reptiles and even some marine mammals like pinnipeds (seals and sea lions) have been observed using gastroliths. These modern examples allow scientists to directly observe gastrolith function, selection behaviors, and wear patterns, creating valuable reference points for interpreting dinosaur fossils. The widespread nature of this adaptation across distantly related animal groups demonstrates its effectiveness as a digestive strategy.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Gastrolith Use

The gastrolith system provided dinosaurs with several significant evolutionary advantages that contributed to their long-term success. Most importantly, it allowed herbivorous dinosaurs to process plant material efficiently without evolving complex dental batteries or specialized chewing mechanisms. This digestive outsourcing freed up evolutionary pathways, potentially enabling the development of other adaptations. For sauropods, gastroliths may have been particularly crucial, as their enormous size required massive food intake, yet their small heads and simple teeth were ill-equipped for extensive chewing. The gastrolith system also provided flexibility in diet, allowing dinosaurs to shift between different plant food sources as seasons or environments changed. By maximizing nutrient extraction from plant material, gastroliths likely supported the gigantism seen in many dinosaur lineages, contributing to their dominance of terrestrial ecosystems for millions of years.

Debated Cases and Scientific Controversies

While gastrolith use is well-established in certain dinosaur groups, the scientific community continues to debate their presence in others. Some alleged gastrolith collections may represent stones coincidentally associated with fossils during preservation. For instance, supposed gastroliths found with certain theropod dinosaurs have faced scrutiny, with some researchers suggesting they might represent stomach contents from prey animals rather than deliberately swallowed grinding stones. Another controversy surrounds whether certain aquatic or semi-aquatic dinosaurs used stones primarily for digestion or for buoyancy control, similar to modern crocodilians. Additionally, the extent to which certain ornithischian dinosaurs with more advanced chewing capabilities relied on gastroliths remains contested. These ongoing debates highlight the challenges in interpreting behavior from fossil evidence and the importance of rigorous analysis before concluding ancient digestive strategies.

How Gastroliths Preserve Dinosaur Dietary Information

Beyond their digestive function, gastroliths serve as valuable scientific time capsules that preserve information about dinosaur diets and behaviors. Microscopic analysis of gastrolith surfaces can reveal trace plant materials embedded in the stone, potentially identifying specific plants the dinosaur consumed. Chemical analysis may detect plant compounds that are transferred to the stone surface during digestion. The wear patterns themselves indicate the type of food being processed – different patterns emerge when grinding woody material versus softer vegetation. In some exceptional fossil cases, gastroliths have been found in association with preserved stomach contents, providing direct evidence of the dinosaur’s last meals. Additionally, the geographical origin of the stones, when different from the local geology, can help paleontologists reconstruct dinosaur movement patterns and habitat use, offering insights into their broader ecological roles.

Gastrolith Replacement and Maintenance

Maintaining an effective set of gastroliths likely required active management throughout a dinosaur’s lifetime. As stones wore down through constant grinding action, they would gradually become smaller and smoother, eventually becoming too polished to effectively grind food. Evidence suggests dinosaurs regularly expelled worn gastroliths and replaced them with fresh, more angular stones. This process may have occurred either through regurgitation or by passing the stones through the digestive tract entirely. Young, growing dinosaurs would have needed to gradually increase their gastrolith quantity as their body size increased. Some paleontologists hypothesize that certain dinosaur species might have engaged in communal gastrolith collection behaviors, potentially teaching juveniles which stones to select. The regular replacement cycle would have created distinctive “gastrolith beds” – concentrated deposits of polished stones that may still be identifiable in certain geological formations today.

Gastroliths and Dinosaur Extinction Theories

The gastrolith system, while highly effective during the Mesozoic era, may have contributed to certain dinosaurs’ vulnerability during the end-Cretaceous extinction event. Herbivorous dinosaurs reliant on gastroliths required regular access to suitable stone sources and abundant vegetation to maintain their complex digestive systems. The catastrophic environmental changes following the Chicxulub asteroid impact, including massive forest fires and extended periods of darkness, would have disrupted both plant growth and potentially dinosaurs’ ability to locate appropriate stones. Additionally, dinosaurs dependent on gastroliths typically had limited oral processing abilities, making it difficult to quickly adapt to alternative food sources during environmental stress. In contrast, mammals with their specialized dentition and different digestive adaptations may have possessed greater dietary flexibility during the extinction crisis. While gastroliths themselves weren’t a direct cause of extinction, the specialized digestive strategy they represented may have limited certain dinosaurs’ adaptive capacity during rapid environmental change.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the gastrolith system represents one of the most fascinating adaptations in dinosaur physiology—a simple yet ingenious solution to the complex challenge of plant digestion. By deliberately swallowing and maintaining collections of carefully selected stones, many dinosaur species effectively created external stomachs, compensating for dental limitations and enabling efficient processing of tough Mesozoic vegetation. This strategy supported the evolution of various specialized body forms and feeding adaptations, contributing significantly to dinosaurs’ 165-million-year dominance of Earth’s terrestrial ecosystems. Today, as paleontologists continue to study these remarkable stones, they provide valuable windows into ancient digestive strategies, dietary preferences, and ecological relationships. The humble gastrolith, once merely a tool for grinding food, now serves as a crucial piece in our ongoing quest to understand the lives of Earth’s most magnificent prehistoric inhabitants.