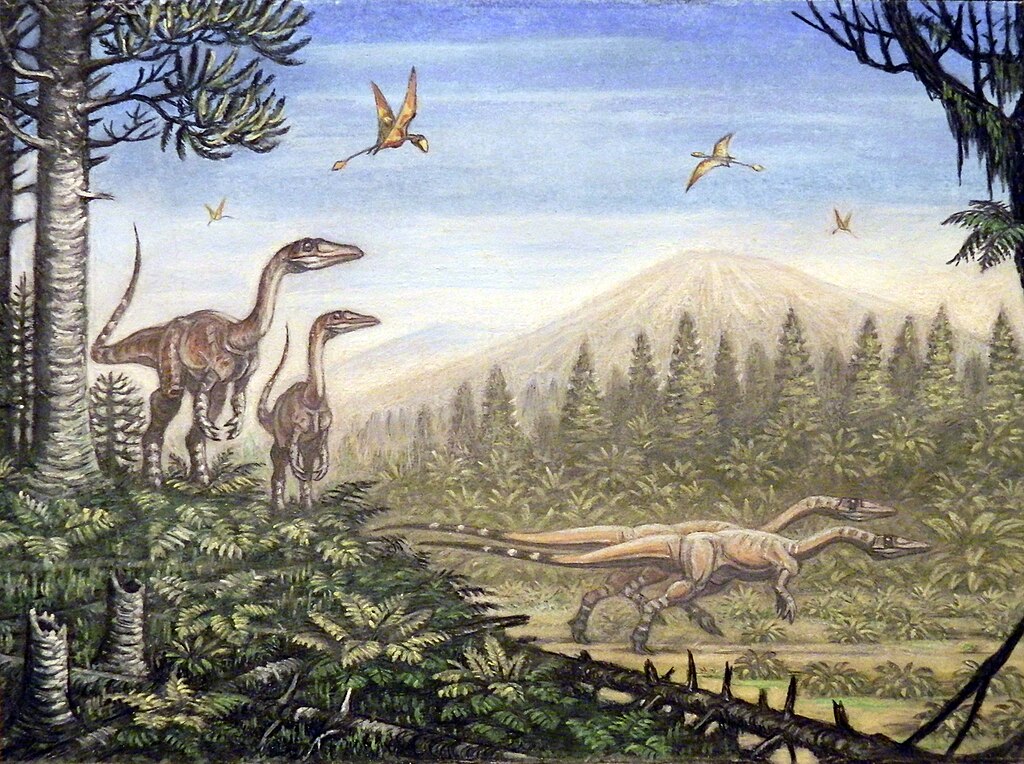

When we imagine dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures, the images that come to mind are largely influenced by scientific discoveries translated through artistic interpretation. Among the most fascinating and informative pieces of evidence that shape these visualizations are fossil footprints, also known as ichnofossils. These preserved tracks offer unique insights that body fossils alone cannot provide, creating a more dynamic understanding of extinct animals. From revealing how creatures moved to indicating social behaviors, footprints have dramatically shaped how artists bring prehistoric life back to visual existence. This article explores the profound relationship between fossil footprints and the artistic reconstructions that help us envision long-vanished worlds.

The Science of Ichnology: Reading Ancient Footprints

Ichnology, the study of trace fossils including footprints, provides paleontologists with critical information about extinct animals’ locomotion, behavior, and environments. Unlike body fossils, which capture anatomical details at the moment of death, footprints represent moments in life—showing animals in motion and interaction. Scientists can determine speed, gait, posture, and weight distribution by analyzing track depth, stride length, and pattern arrangement. This information becomes particularly valuable when body fossils are incomplete or missing entirely. In some cases, fossil footprints have been discovered decades before the corresponding body fossils, allowing scientists to develop hypotheses about unknown creatures based solely on their tracks. The preservation of footprints in specific sediments also offers environmental context that informs artistic depictions of prehistoric landscapes.

From Tracks to Movement: Determining How Extinct Animals Walked

Fossil footprints reveal crucial information about how prehistoric creatures moved through their environment, information that skeletal remains alone cannot provide. By measuring stride length, step angle, and the pressure distribution within footprints, scientists can determine whether an animal was walking, running, or even swimming when its tracks were made. For example, the discovery of sauropod dinosaur tracks with deep heel impressions revolutionized how artists depict these massive creatures, showing they walked with a more elephant-like gait rather than the sprawling posture initially imagined. Similarly, theropod tracks showing toe drag marks have influenced artistic reconstructions by suggesting certain postures during movement. Computer modeling now allows scientists to create biomechanical simulations based on track data, providing artists with accurate references for depicting prehistoric locomotion patterns that would have been impossible to visualize from skeletal remains alone.

Social Behavior Insights from Track Sites

Multiple tracks preserved at single locations offer windows into social behaviors that dramatically influence artistic reconstructions of prehistoric animals. When parallel trackways of similar-sized individuals moving in the same direction are discovered, this provides evidence of potential herding or group movement. Such findings have transformed artistic depictions of certain dinosaur species from solitary hunters to social animals traveling in groups. For instance, the discovery of multiple hadrosaur trackways at various growth stages has led artists to create family group scenes that would have been purely speculative without this ichnological evidence. Track sites revealing predator-prey interactions, such as therapod tracks intersecting with herbivore trails, have inspired dramatic hunting scenes in paleoart. These social behavior insights derived from footprints add narrative elements to artistic reconstructions that make them more compelling and scientifically informed.

Challenging and Confirming Body Fossil Interpretations

Footprints have frequently challenged or confirmed hypotheses based solely on skeletal evidence, leading to significant revisions in artistic reconstructions. One classic example involves the posture of sauropod dinosaurs, which were initially depicted dragging their tails based on skeletal arrangements. However, the consistent absence of tail drag marks in sauropod trackways eventually led scientists to reconsider this interpretation, resulting in modern artistic depictions showing elevated tails. Similarly, footprints have helped resolve debates about limb positioning in certain dinosaur species when skeletal articulation allowed for multiple interpretations. In some remarkable cases, footprints have even provided evidence of animals previously unknown from body fossils, forcing artists to create speculative reconstructions based primarily on track morphology. This dynamic relationship between body fossils and trace fossils continues to refine our visual understanding of prehistoric creatures as new evidence emerges.

Speed and Agility: Redefining Prehistoric Motion

Fossil footprints provide direct evidence of how quickly extinct animals moved, significantly influencing artistic depictions of their locomotion capabilities. By analyzing stride length relative to foot size and applying biomechanical equations, paleontologists can calculate the approximate speed at which tracks were made. This information has transformed artistic reconstructions of certain dinosaurs from sluggish, tail-dragging creatures to agile, dynamic animals. The discovery of running theropod tracks with speeds estimated at over 25 mph has inspired more athletic depictions in modern paleoart. Conversely, the wide stance and relatively short stride length observed in certain sauropod trackways suggests more cautious, deliberate movement for these giants. Artistic reconstructions now frequently incorporate this nuanced understanding of speed variation among different species, creating more accurate and dynamic portrayals of prehistoric movement that align with the ichnological evidence.

Soft Tissue Impressions and Skin Textures

Exceptionally preserved footprints sometimes contain impressions of soft tissues that would not typically fossilize, providing rare glimpses into external anatomy that directly influence artistic reconstructions. Fine-grained sediments can capture skin texture details from the undersides of feet, revealing scale patterns, pad arrangements, and even wrinkles that would otherwise remain unknown. These preserved skin impressions have transformed how artists texture the feet of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals in their reconstructions. In some remarkable cases, footprints have preserved evidence of fleshy pads, claws, and webbing between toes, features that significantly affect how prehistoric feet are depicted in art. Before such discoveries, artists relied primarily on modern animal analogues when depicting foot anatomy, but now many reconstructions incorporate direct evidence from these rare soft tissue impressions. This level of detail adds authenticity to artistic depictions and connects viewers more intimately with creatures that walked the Earth millions of years ago.

Environmental Context and Habitat Reconstruction

Fossil footprints provide valuable environmental context that influences not just the depiction of animals but the entire habitats in which they’re artistically placed. The sediment type preserving tracks—whether mud, sand, volcanic ash, or other materials—indicates specific environmental conditions at the time the prints were made. Ripple marks associated with footprints might suggest shorelines or shallow water environments, while mudcracks indicate seasonal drying. Artists use these environmental clues to create more accurate background settings for their prehistoric reconstructions. The distribution of different animal tracks within a single surface can also reveal ecological relationships and habitat preferences, informing artistic decisions about which species to place together in reconstructed scenes. Some remarkable track sites even preserve plant impressions alongside animal footprints, providing direct evidence of the vegetation that should appear in artistic recreations of these ancient environments.

Revealing Unknown Species Through Their Tracks

In numerous fascinating cases, distinctive footprints have been discovered long before any corresponding body fossils, challenging artists to reconstruct animals known only by their tracks. These “phantom taxa” force paleoartists to make educated inferences based on footprint morphology, size, and movement patterns. The process typically involves comparing the mystery tracks to those of known animals and looking for similarities that might indicate taxonomic relationships. Artists must work closely with ichnologists to create speculative but scientifically grounded reconstructions of these track-makers. One famous example is Cheirotherium, distinctive hand-shaped tracks discovered in the 1830s that were eventually attributed to crocodile-like archosaurs decades later when body fossils were found. These reconstructions based solely on tracks often appear in museum exhibits alongside the footprint evidence, helping visitors understand how scientists interpret such indirect evidence and the degree of certainty or speculation involved.

Digital Modeling and Animation Based on Trackway Data

Advanced technology has revolutionized how scientists and artists translate footprint evidence into dynamic visual reconstructions. Using photogrammetry and 3D scanning, researchers can create precise digital models of fossil trackways that preserve every nuance of the original impressions. These digital models serve as the foundation for sophisticated biomechanical simulations that recreate the walking or running motion that produced the tracks. Artists and animators then use this movement data to inform digital reconstructions and animations that show prehistoric animals in motion with unprecedented accuracy. The integration of pressure data from footprint depth analysis allows for realistic weight distribution and muscle movement in these animations. Museum exhibits increasingly feature these technology-driven reconstructions, allowing visitors to see digital dinosaurs walking precisely as the footprint evidence indicates they did millions of years ago. This marriage of ancient evidence with cutting-edge technology represents one of the most exciting frontiers in visualizing prehistoric life.

Historical Evolution of Track-Influenced Artworks

The influence of fossil footprints on artistic reconstructions has evolved dramatically over the past century, reflecting changing scientific interpretations and artistic approaches. Early 20th-century paleoart largely ignored trackway evidence, resulting in dinosaurs typically depicted with sprawling limbs and dragging tails. The mid-century “Dinosaur Renaissance” marked a turning point as artists like Charles R. Knight began incorporating insights from ichnology into more dynamic, active portrayals. By comparing historical reconstructions from different eras, we can observe how artistic depictions have been progressively refined as footprint evidence has been more thoroughly integrated into scientific understanding. The 1990s saw another revolution with digital technology enabling more sophisticated analysis of tracks and corresponding advances in visual reconstructions. Today’s paleoart reflects a much more nuanced understanding of prehistoric movement and behavior derived from fossil footprints, with artists working more closely with ichnologists than ever before.

Controversies and Alternative Interpretations

The interpretation of fossil footprints isn’t always straightforward, and competing scientific viewpoints often lead to different artistic reconstructions based on the same evidence. Trackways that show unusual patterns may generate multiple hypotheses about the behavior or motion they represent, resulting in various artistic interpretations. For example, certain dinosaur tracks showing only toe impressions have been interpreted as evidence of swimming, with artists depicting dinosaurs paddling through water, while other scientists argue these represent animals walking on their toes across firm ground, inspiring completely different reconstructions. Similarly, disputes about whether certain tracks indicate bipedal or quadrupedal locomotion have led to contrasting artistic depictions of the same species. These scientific debates enrich paleoart by generating diverse visual hypotheses that acknowledge the limits of our knowledge. Museums sometimes display alternative artistic reconstructions side-by-side to educate visitors about the interpretive nature of paleontological evidence and the scientific process.

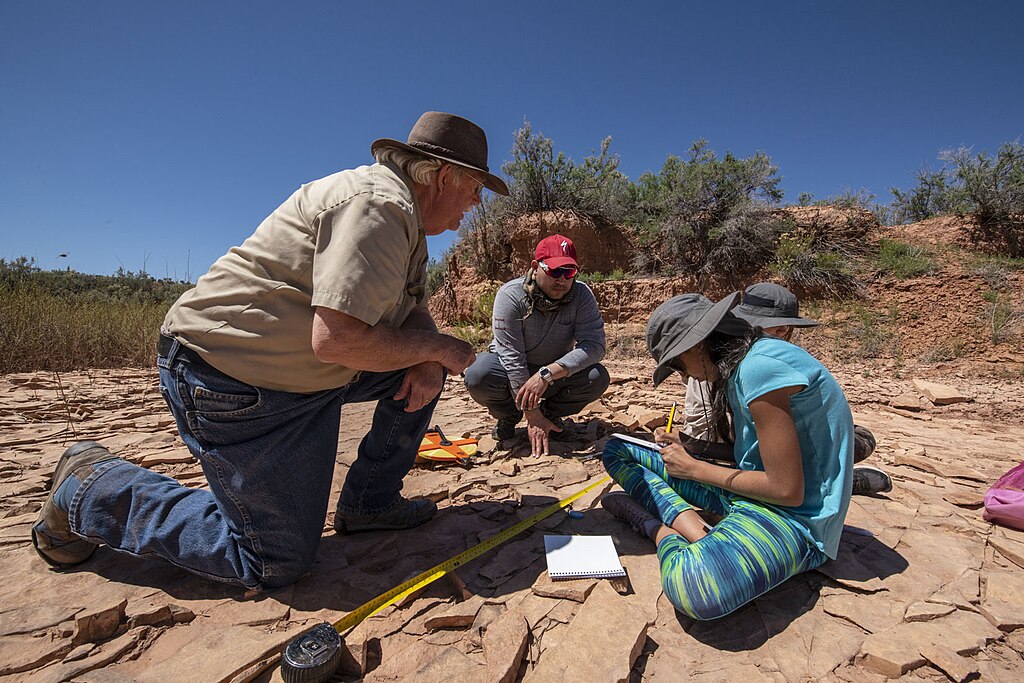

The Artist-Scientist Collaboration Process

Creating scientifically accurate artistic reconstructions based on footprint evidence requires close collaboration between paleoartists and ichnologists. This collaborative process typically begins with scientists providing detailed measurements, photographs, and 3D scans of fossil trackways, along with their interpretations of what these reveal about the track-maker. Artists then develop preliminary sketches incorporating this information, which are reviewed and refined through ongoing dialogue with scientific experts. Many modern paleoartists visit track sites personally to develop a deeper understanding of the evidence and its environmental context. This collaborative approach ensures that artistic liberties don’t compromise scientific accuracy while still allowing artists the creative freedom to breathe life into ancient creatures. The most successful collaborations produce reconstructions that are both scientifically credible and aesthetically compelling, advancing public understanding while acknowledging the boundaries between established fact and informed speculation.

Future Directions in Track-Based Reconstructions

Emerging technologies and methodological advances promise to further enhance how fossil footprints influence artistic reconstructions in coming years. Machine learning algorithms are being developed to analyze thousands of modern animal tracks and create predictive models that can be applied to fossil footprints, potentially revealing subtleties of movement currently overlooked. Virtual reality environments based on fossil trackway data may soon allow people to walk alongside digital recreations of prehistoric animals moving exactly as their tracks indicate they once did. Advances in understanding the relationship between foot morphology and trackway characteristics will likely enable more precise reconstructions of foot anatomy from tracks alone. As climate change accelerates erosion in some regions, previously hidden trackways are being exposed, providing new evidence that will undoubtedly challenge existing artistic interpretations. The continuing discovery of exceptional tracks preserving skin impressions and other details will allow for increasingly nuanced visual reconstructions that bridge the gap between scientific evidence and imaginative visualization.

Conclusion

Fossil footprints offer a unique window into prehistoric life that fundamentally shapes our visual understanding of extinct animals. From revealing how creatures moved to providing insights into their social behaviors and habitats, tracks provide dynamic information that complements skeletal remains. As technologies for analyzing and visualizing this evidence continue to advance, the artistic reconstructions they inspire become increasingly sophisticated and scientifically informed. The ongoing collaboration between ichnologists and artists ensures that each new footprint discovery can potentially transform how we envision creatures that walked the Earth millions of years ago. These reconstructions do more than satisfy scientific curiosity—they connect us emotionally to our planet’s ancient past, allowing us to envision long-vanished worlds with increasing clarity and confidence.