Mary Anning, a pioneering paleontologist from Lyme Regis, England, transformed our understanding of ancient life through her remarkable fossil discoveries during the early 19th century. Working against the social and scientific constraints of her era, this self-taught fossil hunter unearthed specimens that challenged existing beliefs about Earth’s history and the creatures that once inhabited it. Her meticulous excavations along the Jurassic Coast revealed previously unknown marine reptiles and other prehistoric creatures, providing crucial evidence that would eventually support theories of extinction and evolution. Despite receiving limited recognition during her lifetime, Anning’s contributions proved foundational to paleontology as we know it today, permanently altering our conception of prehistoric life and the dynamic nature of Earth’s biological history.

The Making of a Fossil Hunter

Mary Anning’s journey into paleontology began in the most unlikely circumstances along the dangerous cliffs of Lyme Regis, England, where she was born in 1799 to a poor family. Her father, Richard Anning, supplemented the family’s meager income by collecting and selling “curiosities” – fossils found in the coastal cliffs – to tourists, teaching young Mary how to identify and extract specimens from the crumbling Blue Lias formation. After her father’s death in 1810, Mary, just eleven years old, took up fossil hunting out of necessity, turning her natural curiosity and developing expertise into her family’s primary source of income. The harsh coastal environment became her classroom, with winter storms exposing new fossils in freshly collapsed cliffs, while the dangerous tides and frequent landslides posed constant threats to her safety. Despite minimal formal education and no scientific training, Mary developed an extraordinary eye for spotting fossils others missed and a remarkable skill in extracting delicate specimens intact, qualities that would eventually earn her reluctant respect from the male-dominated scientific community of Georgian England.

The Ichthyosaurus Discovery

In 1811, when Mary was just twelve years old, her brother Joseph spotted what appeared to be a large skull embedded in the cliff face. Mary subsequently excavated the remainder of the specimen over the following months, revealing the first complete Ichthyosaurus (or “fish lizard”) skeleton known to science. This remarkable marine reptile, approximately 5.2 meters long, presented features previously unknown to naturalists—a crocodile-like head, paddled limbs, and fish-like vertebrae that defied easy classification within existing taxonomic frameworks. The discovery was initially attributed to her brother, and later purchased by Henry Hoste Henley of Colway Manor for £23, a significant sum for the struggling Anning family. When the specimen was eventually studied and described by Sir Everard Home in 1814, it challenged prevailing notions about reptilian evolution and marine adaptations. The Ichthyosaurus discovery established a pattern that would define Anning’s career: unearthing extraordinary specimens that raised fundamental questions about the diversity of ancient life forms, while receiving minimal credit or financial compensation proportionate to their scientific significance.

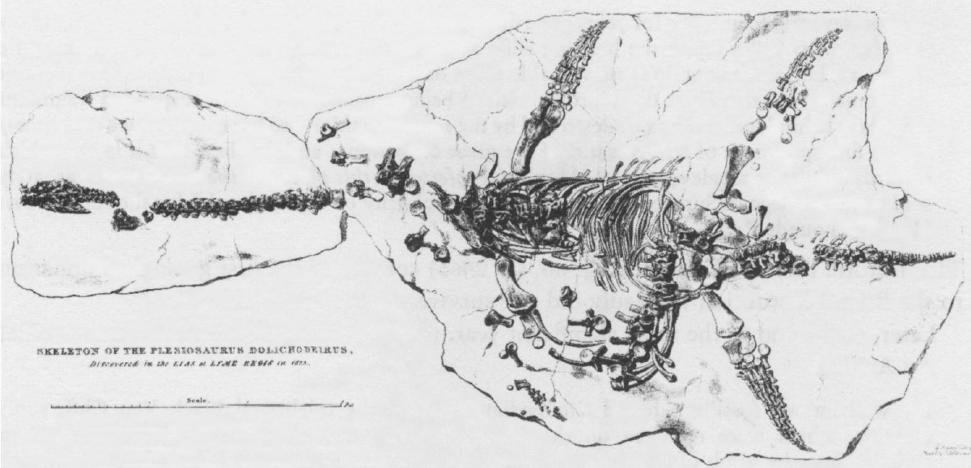

Plesiosaur: A Revolutionary Find

Mary Anning’s discovery of the first complete plesiosaur skeleton in 1823 represents one of her most significant contributions to paleontology. This extraordinary marine reptile, with its remarkably long neck, tiny head, and four paddle-like limbs, was so unusual that many scientists initially suspected a hoax. Georges Cuvier, the leading anatomist of the time, questioned its authenticity until further evidence convinced him of the creature’s remarkable form. The plesiosaur exemplified a body plan entirely unknown in living animals, with proportions that seemed to defy functional logic—a neck containing more than 35 vertebrae that stretched longer than the animal’s body. When the specimen was presented at the Geological Society of London, it generated intense scientific debate, though as a woman, Anning was not permitted to attend the meeting or participate in the discussions about her own discovery. The plesiosaur provided compelling evidence that Earth’s ancient ecosystems had been populated by creatures fundamentally different from modern animals, strengthening emerging concepts about extinction and the deep history of life on our planet.

Unveiling the Pterodactyl

In 1828, Mary Anning made history once again by discovering the first complete pterodactyl skeleton found in Britain. The flying reptile, later classified as Dimorphodon macronyx, represented the first pterosaur specimen recovered outside Germany, expanding scientists’ understanding of these creatures’ geographic distribution. The remarkably preserved specimen displayed the distinctive hollow bones, wing membranes, and elongated fourth finger that characterized these airborne reptiles, yet it differed significantly from previously discovered pterosaurs in having a proportionally larger head and shorter wingspan. William Buckland, an Oxford geologist and one of Anning’s scientific correspondents, presented the discovery to the Geological Society of London, publishing a description that firmly established it as a new species. The pterodactyl discovery provided crucial evidence that diverse flying reptiles had existed alongside marine reptiles in Mesozoic ecosystems, helping scientists construct a more comprehensive picture of prehistoric food webs and ecological relationships. Notably, Anning’s fossil demonstrated adaptations for aerial locomotion that evolved independently from those of birds and bats, revealing the remarkable evolutionary innovations that had occurred across the reptilian lineage.

The Significance of Coprolites

Mary Anning made a pivotal contribution to paleontology through her work with fossilized feces, which became known as coprolites. Initially referred to as “bezoar stones,” these spiral-shaped fossils had long puzzled collectors until Anning observed similar structures inside the body cavities of ichthyosaur skeletons, leading her to propose they were fossilized intestinal contents. Her insightful hypothesis was later confirmed by William Buckland, who published a paper on the subject in 1829, crediting Anning for drawing his attention to the structures. These coprolites provided unprecedented insights into the diets and digestive systems of extinct creatures, revealing fish scales and bones within ichthyosaur droppings that confirmed their predatory nature. The study of coprolites opened an entirely new field of paleontological investigation, allowing scientists to reconstruct prehistoric food webs and ecological relationships with greater accuracy than was possible from skeletal remains alone. Through this discovery, Anning demonstrated that understanding extinct animals required looking beyond their anatomy to consider their biological functions and interactions—a conceptual advancement that significantly enriched paleontological interpretation.

Scientific Recognition and Systematic Exclusion

Despite her extraordinary contributions to paleontology, Mary Anning faced systematic barriers to full scientific recognition due to her gender, class, and lack of formal education. The scientific societies of early 19th-century Britain—particularly the Geological Society of London—excluded women from membership and even from attending meetings as guests, effectively preventing Anning from participating in discussions of her own discoveries. When her fossils were studied and published upon by geologists like William Buckland, Henry De la Beche, and William Conybeare, Anning was rarely credited properly, with many papers mentioning her only in passing or not at all. This pattern of erasure was somewhat mitigated by a few more supportive scientists, including the geologist Henry De la Beche, who created the watercolor “Duria Antiquior” based on Anning’s discoveries and sold prints to benefit her financially during particularly difficult times. The renowned anatomist Richard Owen, while benefiting tremendously from studying her specimens, was notorious for failing to acknowledge her contributions in his publications. Despite these challenges, Anning gradually earned respect within scientific circles, corresponding with leading geologists and receiving occasional visitors like the Swiss naturalist Louis Agassiz, who traveled to Lyme Regis specifically to consult her expertise on fossil fish.

Challenging Biblical Narratives

Mary Anning’s fossil discoveries emerged during a period of profound theological and scientific tension, when the prevailing interpretation of Earth’s history was still largely based on biblical accounts. Her specimens of extinct marine reptiles presented a direct challenge to literalist readings of Genesis, as they represented creatures that no longer existed, contradicting the belief that God’s creation had remained unchanged since the beginning. The sheer antiquity suggested by the rock layers in which these fossils were found dramatically expanded the perceived timeline of Earth’s history beyond the approximately 6,000 years calculated by Archbishop James Ussher’s biblical chronology. While Anning herself maintained religious beliefs throughout her life, her discoveries became inadvertent ammunition in the growing debate between catastrophism—which attempted to reconcile fossils with biblical floods—and the emerging gradualist views that would eventually lead to modern geological understanding. Notably, prominent geologists who studied Anning’s fossils, including William Buckland and Adam Sedgwick, were also ordained Anglican clergymen who struggled to reconcile the growing fossil evidence with their theological commitments, ultimately helping to forge compromises between religious and scientific worldviews.

Contributions to Early Evolutionary Thought

Though Mary Anning died fifteen years before Darwin published “On the Origin of Species,” her fossil discoveries provided crucial evidence that later supported evolutionary theory. The succession of different marine reptiles she uncovered from different rock layers demonstrated that Earth’s inhabitants had changed dramatically over time, with certain life forms disappearing completely while new ones emerged. Her meticulous observation of anatomical details revealed strange combinations of features—like the fishlike vertebrae and reptilian skull of ichthyosaurs—that suggested evolutionary transitions between major animal groups. When Charles Lyell incorporated descriptions of Anning’s fossils into his influential “Principles of Geology,” which Darwin carried aboard the HMS Beagle, her discoveries indirectly shaped Darwin’s thinking about the mutability of species. Her plesiosaurs and pterosaurs, with their seemingly improbable anatomical configurations, challenged the notion that all creatures were perfectly designed, instead suggesting adaptation to specific environmental conditions—a concept central to Darwin’s later theory. Though Anning never explicitly endorsed transmutation (the pre-Darwinian term for evolution), her discoveries provided indispensable pieces of the puzzle that natural scientists would eventually assemble into evolutionary theory.

The Belemnite Breakthrough

Among Mary Anning’s more overlooked but scientifically significant contributions was her discovery of belemnite fossils with preserved ink sacs in 1826. These cigar-shaped fossils had long been known, but their biological nature remained poorly understood until Anning found specimens showing soft tissue preservation, conclusively demonstrating their relationship to modern squids and cuttlefish. The preserved ink sacs contained dried ink that could still be reconstituted with water—remarkably, some artists of the period, including her friend Henry De la Beche, actually used this Jurassic ink to create drawings of the ancient creatures. Anning’s belemnite discoveries provided a crucial link between modern cephalopods and their ancient relatives, demonstrating evolutionary continuity across more than 200 million years. The specimens showed that certain biological features, like defensive ink production, had remained remarkably consistent despite significant changes in other aspects of cephalopod anatomy. This work on belemnites also advanced understanding of exceptional preservation conditions, raising questions about how soft tissues could survive fossilization processes—questions that continue to drive paleontological research today.

Establishing Lyme Regis as a Paleontological Hub

Mary Anning’s reputation for extraordinary fossil discoveries transformed the small coastal town of Lyme Regis into an internationally significant site for paleontological research and tourism. Her small fossil shop on what became known as “Fossil Beach” drew visitors from across Britain and Europe, including professional scientists, aristocratic collectors, and curious travelers seeking specimens or simply hoping to meet the famous “fossil woman” herself. Through her extensive knowledge of the local stratigraphy, Anning effectively created a detailed map of the fossil-bearing layers along the Dorset coast, developing a level of site-specific expertise that allowed her to predict where particular types of fossils might be found. This localized knowledge proved invaluable to visiting geologists attempting to establish broader correlations between rock formations across Britain and the European continent. The scientific importance of Lyme Regis continued after Anning’s death, with the area’s Jurassic marine fossils proving crucial for comparative studies with continental specimens, ultimately contributing to the development of biostratigraphy—using fossil assemblages to determine the relative ages of rock formations. Today, the Jurassic Coast, including Anning’s hunting grounds, is recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, with the Lyme Regis Museum and annual fossil festivals celebrating her legacy.

Financial Struggles and Scientific Commerce

Despite her scientific contributions, Mary Anning spent most of her life in precarious financial circumstances, dependent on the commercial sale of fossils to support herself and her mother. The fossil trade operated within a complex socioeconomic framework, with Anning occupying the vulnerable position of a working-class supplier to wealthy collectors and institutions. Her income varied dramatically with the seasons and economic conditions, with harsh winters preventing fossil collection while also exposing new specimens through coastal erosion. Particularly impressive specimens could command significant prices—her first complete plesiosaur sold for £100, approximately equivalent to a full year’s income for a skilled tradesperson—but such major discoveries were unpredictable and infrequent. The financial pressure often forced Anning to sell specimens immediately rather than waiting for higher offers, with many of her most significant finds quickly disappearing into private collections where they remained inaccessible to broader scientific study. Her financial situation improved somewhat when the British Association for the Advancement of Science awarded her an annual stipend of £25 in 1838, and again when the Geological Society took up a collection to assist her during a period of illness in 1846, though these gestures came late in her life and reflected recognition that her scientific contributions had never been properly compensated.

Legacy and Delayed Recognition

Mary Anning died of breast cancer in 1847 at the age of 47, her contributions to science largely unacknowledged during her lifetime beyond a small circle of geologists and paleontologists familiar with her work. Her obituary in the Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society—an organization that had never permitted her to attend its meetings—represented the first time her name appeared in their publications, despite her specimens having been discussed in their proceedings for decades. The true significance of Anning’s contributions would only be fully appreciated more than a century after her death, as historians of science began to recover the overlooked role of women in scientific advancement. In 2010, the Royal Society included Anning in a list of the ten British women who have most influenced the history of science, finally placing her alongside figures like Caroline Herschel and Rosalind Franklin. Her life has inspired numerous books, films, and the famous tongue-twister “She sells seashells by the seashore,” which is widely believed to reference Anning’s fossil work. Perhaps most significantly, the Geological Society of London—which had excluded her during her lifetime—commissioned a stained glass window in her honor at the parish church in Lyme Regis in 1850, and in 2018, finally acknowledged her contributions by placing her portrait in their headquarters alongside the male scientists whose careers she had helped build.

Conclusion

Mary Anning’s remarkable fossil discoveries fundamentally transformed our understanding of Earth’s prehistoric past. Working with limited resources and against significant social barriers, she unearthed creatures that challenged existing knowledge and expanded the scientific community’s conception of what life forms were possible. The marine reptiles, flying pterosaurs, and other specimens she meticulously excavated from the Jurassic cliffs of Lyme Regis provided essential evidence for extinction, the deep history of life on Earth, and eventually for evolutionary theory. Though recognition of her contributions was scandalously delayed, Anning’s legacy endures in museums worldwide that display her discoveries, in the scientific understanding her work helped build, and in the inspiration she provides to generations of women in science. Her story reminds us that scientific progress often comes from unexpected sources, and that the history of any discipline must be continually reexamined to ensure that vital contributions are not overlooked due to the gender, class, or educational background of those who made them.