Picture yourself diving into an ancient ocean 100 million years ago, where creatures beyond your wildest nightmares lurked beneath the waves. The Cretaceous period wasn’t just about towering dinosaurs on land – the real action was happening underwater, where some of the most terrifying and magnificent predators in Earth’s history battled for supremacy. This watery realm was far more dangerous and complex than any modern ocean ecosystem we know today.

The Rise of Marine Superpredators

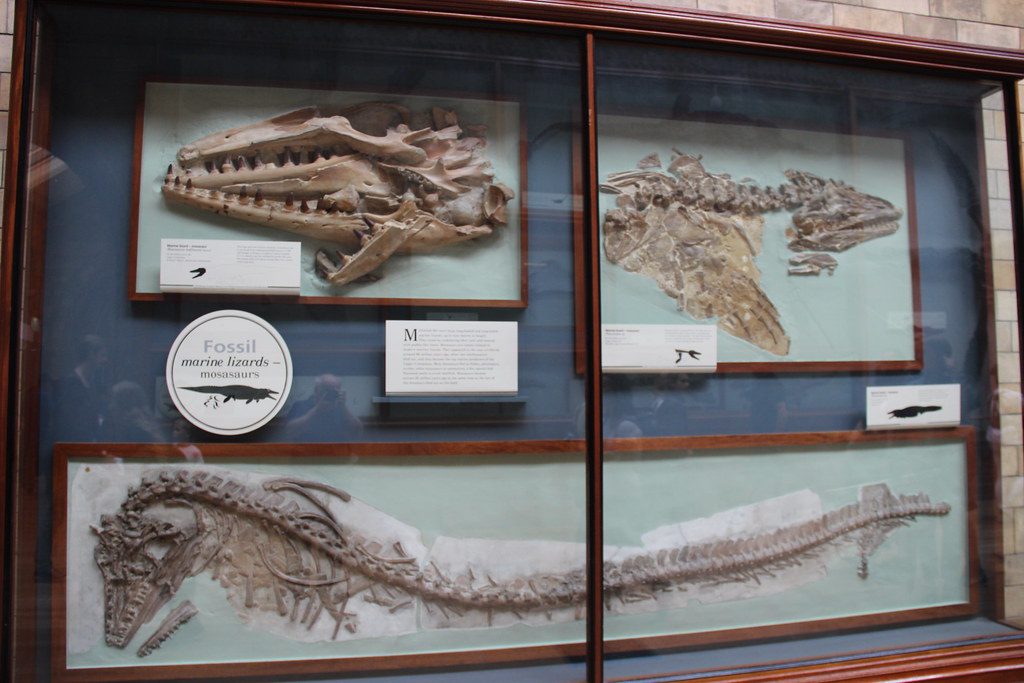

The Cretaceous seas witnessed something extraordinary – the emergence of marine reptiles that would make today’s great whites look like goldfish. This period, spanning from around 145 to 66 million years ago, saw mosasaurs and plesiosaurs reigning supreme in Earth’s seas. These weren’t your average sea creatures; they were evolutionary marvels that had completely mastered aquatic life.

What made these predators so successful was their incredible diversity. There were more than a dozen groups of marine reptiles in the Mesozoic, of which four had more than 30 genera, namely sauropterygians (including plesiosaurs), ichthyopterygians, mosasaurs, and sea turtles. Each group filled a different niche in this underwater ecosystem, creating a complex food web that supported massive biodiversity.

Mosasaurs: The Ocean’s Ultimate Killers

Mosasaurs were a group of large, aquatic squamates (relatives of modern-day lizards and snakes) which became the dominant marine predators towards the end of the Cretaceous period. Think of them as the T. rex of the seas, but potentially even more fearsome. These monsters could reach lengths of up to 50 feet, with powerful paddle-like limbs and jaws filled with razor-sharp teeth.

The hunting strategies of mosasaurs were absolutely brutal. They were fierce predators with hunting strategies similar to those of modern-day sharks and killer whales, using their powerful jaws to tear apart prey with their strong bite force and sharp teeth. What’s particularly chilling is that they weren’t picky eaters – fossil evidence shows they devoured fish, sharks, squid, and even other marine reptiles, including smaller mosasaurs.

Plesiosaurs: Masters of Underwater Flight

While mosasaurs were the late-comers to the party, plesiosaurs had been perfecting their aquatic dominance for much longer. Sauropterygia and Ichthyopterygia were the two longest surviving lineages, with 185 and 160 million years of stratigraphic spans, respectively. These remarkable creatures came in two distinct body plans that would define underwater predation for millions of years.

The long-necked plesiosaurs were like underwater giraffes with attitude. Some Plesiosaurs, like Elasmosaurus, had incredibly long necks, while others, like Liopleurodon, had much shorter necks. Their hunting strategy was pure stealth – that impossibly long neck could snake through the water to snatch unsuspecting prey while their body remained hidden. The short-necked varieties, however, were built for pursuit hunting, using their massive heads and powerful flippers to chase down faster prey.

Ichthyosaurs: The Dolphin Mimics

Perhaps the most remarkable marine reptiles were the ichthyosaurs – creatures that looked so much like dolphins that it’s hard to believe they weren’t related. Ichthyosaurians thrived during much of the Mesozoic era, appearing around 250 million years ago and surviving until about 90 million years ago, evolving from land reptiles that returned to the sea in a development similar to how mammalian ancestors of modern dolphins and whales returned to the sea.

These marine reptiles pushed the boundaries of what was possible in aquatic environments. Temnodontosaurus, with eyes that had a diameter of twenty-five centimeters, could probably still see at a depth of 1,600 meters, while later species such as Ophthalmosaurus had relatively larger eyes, indicating that diving capacity was better in late Jurassic and Cretaceous forms. Their enormous eyes weren’t just for show – they were deep-sea hunting machines that could track prey in the eternal darkness of the ocean depths.

The Late Arrivals That Changed Everything

One of the most fascinating aspects of Cretaceous ocean dynamics was the timing of different groups’ dominance. Mosasaurs were relative latecomers during the span of the Mesozoic, with the first mosasaur not emerging until the late Cretaceous about 99 million years ago, but in a short period of time, they quickly diversified. This rapid evolution and diversification shows just how dynamic these ancient oceans were.

The speed at which mosasaurs took over is mind-boggling. In geological terms, it happened almost overnight. Some developed bulbous teeth that they used to hammer away at oyster-like bivalves, while others developed razor-like teeth that could pierce and shred larger prey, including other mosasaurs, with most living in shallow waters but some, like Tylosaurus, traveling far offshore and diving to deeper depths.

Global Dominance and Distribution

The reach of these marine predators was truly global. Fossils of mosasaurs have been found on every continent, including Antarctica, indicating they lived throughout the entire globe. This worldwide distribution tells us something crucial about the Cretaceous oceans – they were warm enough and productive enough to support massive predators everywhere on the planet.

The diversity of marine ecosystems during this time was staggering. The Mesozoic seas were thriving ecosystems structured much like the ecosystems that exist today, with phytoplankton forming the base of the food web and large predators at the top, while the higher sea level during the Jurassic and Cenozoic created large areas of shallow seas where toothed fish, reptiles, birds, and flying pterosaurs stalked their prey.

The Supporting Cast of Ocean Predators

The story of Cretaceous seas wasn’t just about giant marine reptiles. The first teleost fishes, fish with mobile jaws, evolved and their gaping, flexible mouths were effective for gulping prey, with carnivorous fishes like Xiphactinus becoming the most numerous predators in the Late Cretaceous seas. These bony fish were no joke – some reached lengths of 20 feet and had jaws that could unhinge like a snake’s.

Even the skies above the oceans were dangerous. The Hesperornithiformes were flightless, marine diving birds that swam like grebes, essentially prehistoric penguins with teeth. These toothed birds filled yet another ecological niche, showing how thoroughly every possible way of life in and around the Cretaceous oceans was exploited by different groups of animals.

A Food Web Under Pressure

Despite their dominance, cracks were already beginning to show in this marine paradise. The last ichthyosaurs died out around 90 million years ago during the Cretaceous after they were unable to adapt to changes in the ocean and the extinction of some of their food sources, while plesiosaurs lasted until the end of the Cretaceous. The oceans were changing, becoming more challenging even for these supremely adapted predators.

The end was approaching faster than anyone could have predicted. The demise of the ichthyosaurs was described as a two-step process, with a first extinction event eliminating two of the three ichthyosaur feeding guilds still present, leaving only an unspecialized apex predator group, followed by a second extinction event during the Cenomanian-Turonian boundary event after which just a single lineage survived.

The Great Collapse

Then came the catastrophe that ended it all. The impact of a 6.2-mile asteroid triggered mass extinctions on land and sea, with dust and soot lingering in the atmosphere, blocking sunlight and causing Earth’s temperature to drop, killing many plants on land and phytoplankton in the sea, which caused ecosystems across the globe to collapse. The interconnected nature of these marine food webs became their downfall – when the base collapsed, everything above it came crashing down.

The scale of marine devastation was unprecedented. Ammonites, large marine reptiles, rudist clams, and many species of phytoplankton were particularly hard hit in the ocean, with molluscs including ammonites, rudists, freshwater snails, and mussels becoming extinct or suffering heavy losses, and ammonites thought to have been the principal food of mosasaurs. When your primary food source disappears, even being a 50-foot marine killing machine can’t save you.

Legacy of the Ocean’s Former Rulers

The extinction of these marine giants left a void that has never been filled in quite the same way. The K/Pg extinction cleared the way for new lineages of life to thrive, with mammals taking advantage of the dinosaurs’ extinction and evolving in new directions, with some lineages eventually giving rise to the whales, seals, and manatees that live in the ocean today. But these modern marine mammals, impressive as they are, never quite matched the sheer diversity and alien magnificence of their Cretaceous predecessors.

What makes the Cretaceous marine extinction particularly tragic is how complete it was. The mosasaurs became extinct, while the impact’s blockage of sunlight devastated marine food webs which relied on photosynthetic plankton, potentially returning the oceans to a single-celled state that the world had not seen in over half a billion years. The sophisticated marine ecosystems that had taken millions of years to evolve were wiped out in what was essentially an instant in geological terms.

The Cretaceous oceans were ruled not by a single king, but by an entire dynasty of marine reptiles that pushed the boundaries of size, intelligence, and predatory sophistication. From the late-arriving but devastatingly effective mosasaurs to the long-lived and diverse plesiosaurs, these creatures created marine ecosystems more complex and dangerous than anything our modern oceans have ever seen. Their sudden disappearance 66 million years ago didn’t just end the age of marine reptiles – it closed a chapter in Earth’s history that will never be repeated. Makes you wonder what other incredible worlds we’ve lost to the passage of time, doesn’t it?