The Jurassic period wasn’t just a time of giant herbivores munching on ferns. Picture this: massive carnivorous dinosaurs stalking through ancient forests, their razor-sharp teeth gleaming in the prehistoric sunlight. These weren’t your typical backyard predators – they were killing machines that ruled their ecosystems with an iron fist. From the depths of primordial oceans to the canopies of towering conifers, apex predators dominated every corner of the Jurassic world. Their reign of terror lasted over 56 million years, shaping evolution in ways we’re still discovering today.

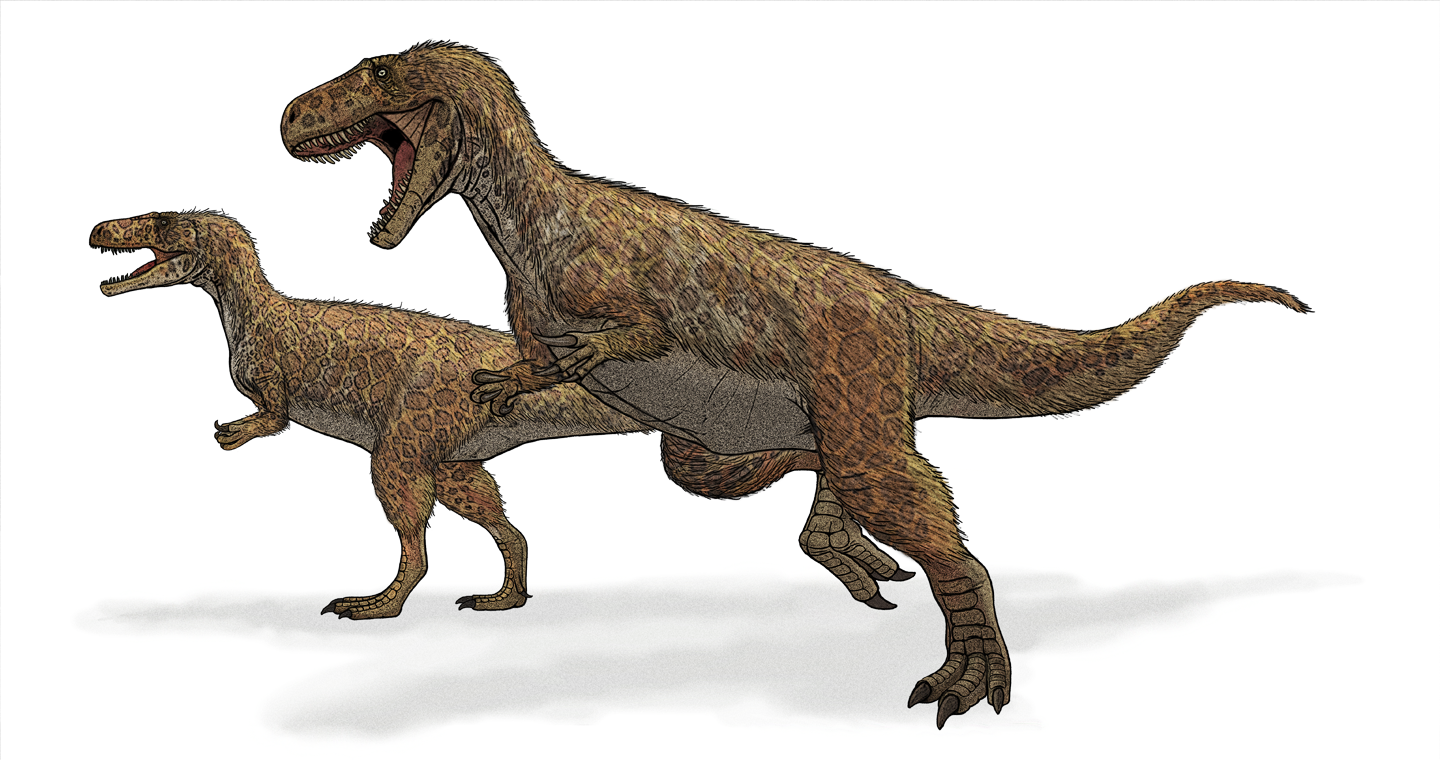

Allosaurus: The Butcher of the Late Jurassic

When you think of Jurassic predators, Allosaurus probably springs to mind first. This 28-foot-long nightmare was built like a biological weapon, with arms that could bench press a small car and claws designed to slice through flesh like butter. Scientists have found evidence of Allosaurus attacks on massive sauropods, proving these predators weren’t afraid to take on prey many times their size.

What made Allosaurus truly terrifying wasn’t just its size, but its hunting strategy. These predators likely hunted in coordinated groups, using their superior intelligence to outmaneuver even the largest herbivores. Their bite force could crush bones, while their powerful legs allowed them to chase down prey at speeds approaching 25 mph.

Ceratosaurus: The Horned Devil

Imagine a crocodile crossed with a freight train, and you’re getting close to understanding Ceratosaurus. This distinctive predator sported a prominent horn on its snout, giving it an appearance that would make modern-day rhinos jealous. Unlike its cousin Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus preferred hunting near water sources, making it the apex predator of Jurassic wetlands.

The horn wasn’t just for show – it likely served as both a display feature and a weapon during territorial disputes. Ceratosaurus also had unusually robust teeth compared to other theropods, suggesting it could crack through turtle shells and thick-skinned prey that other predators couldn’t handle.

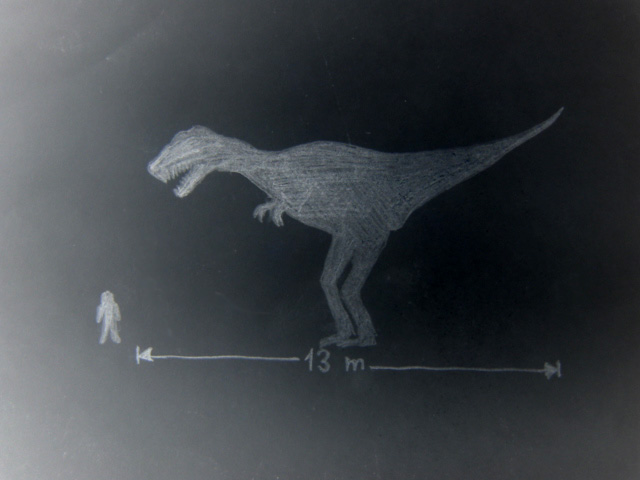

Megalosaurus: The First Discovered Giant

Long before Allosaurus made headlines, Megalosaurus was terrorizing the Middle Jurassic landscape. This 30-foot predator holds the distinction of being the first dinosaur ever scientifically named, discovered in English quarries back in 1824. Its massive jaw could deliver a bite force comparable to a modern great white shark, but with the added bonus of serrated teeth designed for tearing flesh.

What’s fascinating about Megalosaurus is how it adapted to hunt in dense forest environments. Its relatively shorter legs compared to other large theropods suggest it was more of an ambush predator, lying in wait among the thick vegetation before launching surprise attacks on unsuspecting herbivores.

Torvosaurus: The European Titan

If Allosaurus was the king of North America, then Torvosaurus ruled Europe with an iron fist. This massive predator could reach lengths of up to 36 feet, making it one of the largest land predators of its time. Its arms were proportionally longer than those of T. rex, ending in massive claws that could disembowel prey with a single swipe.

Torvosaurus had an unusual hunting advantage – its teeth were blade-like and compressed, perfect for slicing through flesh rather than crushing bones. This adaptation allowed it to quickly disable large prey and avoid prolonged struggles that might attract other predators or result in injury.

Yangchuanosaurus: Asia’s Apex Hunter

While Western dinosaurs get most of the attention, Asia had its own terrifying apex predator in Yangchuanosaurus. This Chinese giant reached lengths of 35 feet and possessed some of the most powerful jaw muscles ever recorded in a theropod dinosaur. Its skull alone measured over three feet long, housing teeth the size of railroad spikes.

What set Yangchuanosaurus apart was its incredibly robust build. Unlike the more gracile Allosaurus, this predator was built like a tank, capable of taking down the largest sauropods through sheer brute force. Its bite could generate pressures exceeding 3,000 pounds per square inch.

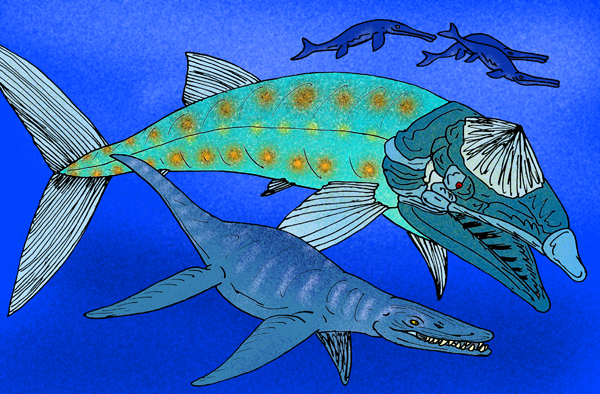

Leedsichthys: The Ocean’s Gentle Giant Predator

Not all apex predators were land-dwelling monsters. Leedsichthys problematicus was a massive bony fish that could reach lengths of up to 55 feet, making it larger than most modern whales. Despite its enormous size, this oceanic giant was actually a filter feeder, using its massive mouth to strain plankton and small fish from the water.

While Leedsichthys wasn’t technically a predator in the traditional sense, its sheer size made it the apex species of Jurassic seas. Its presence influenced the entire marine ecosystem, and its feeding habits helped shape the evolution of smaller marine life throughout the period.

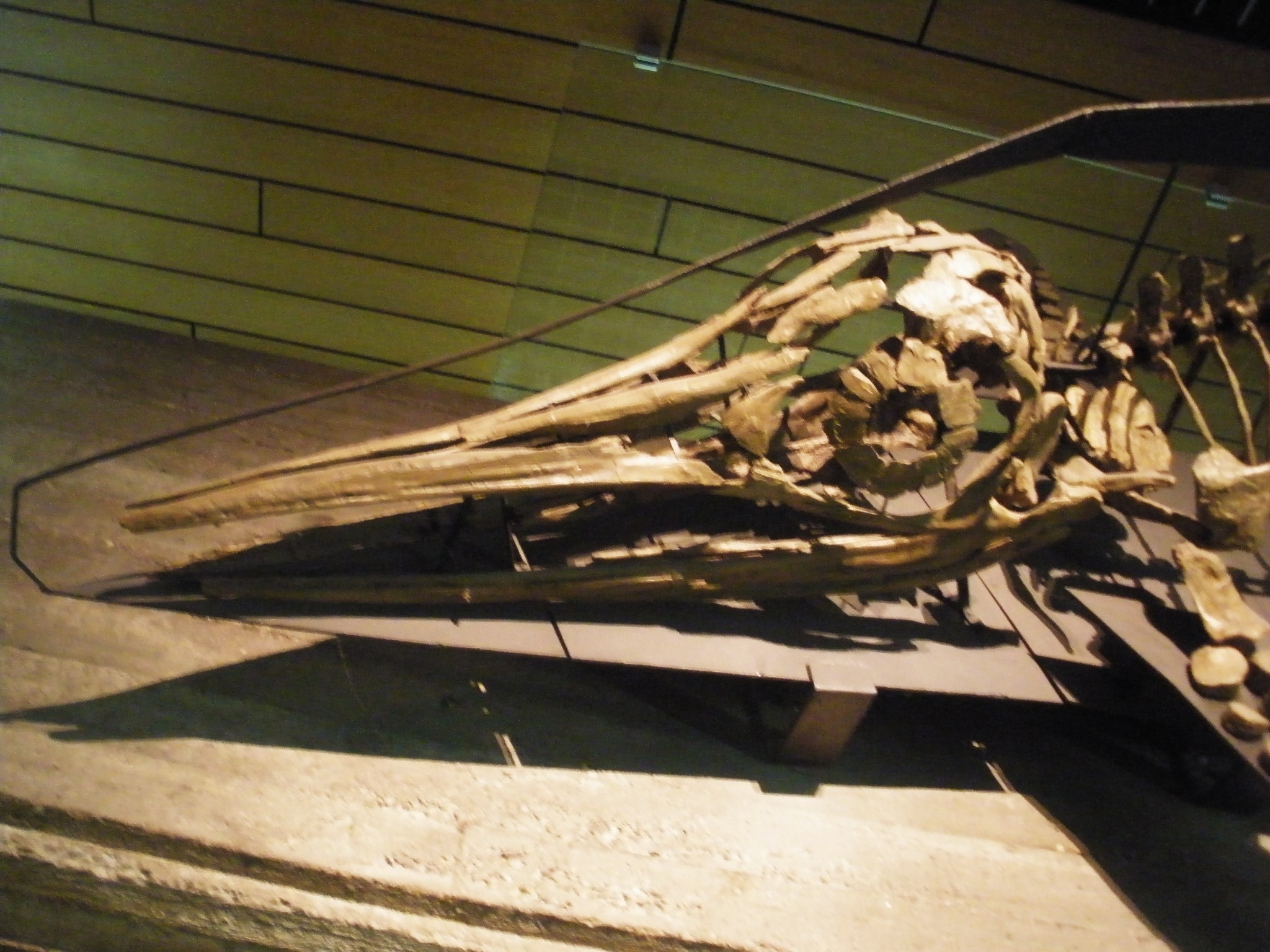

Pliosaurus: The T. rex of the Seas

If you thought land predators were scary, wait until you meet Pliosaurus. This marine reptile was essentially a 50-foot-long crocodile with flippers, capable of generating bite forces that would make a T. rex weep. Its skull alone measured 8 feet in length, packed with teeth the size of bananas.

Pliosaurus dominated the Jurassic seas like no other predator. It could take down other marine reptiles, large fish, and even attack dinosaurs that ventured too close to the water’s edge. Its four massive flippers allowed it to reach speeds of up to 25 mph underwater, making it faster than most modern sharks.

Cryptoclidus: The Long-Necked Sea Serpent

While not as massive as Pliosaurus, Cryptoclidus was the perfect example of evolutionary specialization. This 26-foot-long plesiosaur used its incredibly long neck – longer than its body – to sneak up on schools of fish and squid. Its small head and needle-like teeth were perfectly adapted for catching slippery prey.

Cryptoclidus represents a different kind of apex predator – one that relied on stealth and precision rather than brute force. Its hunting strategy was like that of a modern-day snake, using its flexible neck to strike at prey from unexpected angles while keeping its body hidden in the depths.

Ophthalmosaurus: The Dolphin-Like Hunter

Picture a dolphin, but make it 20 feet long with teeth like a crocodile, and you’ve got Ophthalmosaurus. This ichthyosaur was the speed demon of Jurassic oceans, capable of diving to incredible depths and chasing down the fastest fish. Its enormous eyes – some of the largest relative to body size of any vertebrate – allowed it to hunt in the darkest depths.

What made Ophthalmosaurus truly remarkable was its warm-blooded metabolism, allowing it to maintain high activity levels even in cold, deep waters. This gave it a significant advantage over cold-blooded marine reptiles and established it as the apex predator of the open ocean.

Compsognathus: The Tiny Terror

Not all apex predators were giants. Compsognathus, standing only 2 feet tall, was the apex predator of its particular niche – small prey. This chicken-sized dinosaur was incredibly fast and agile, capable of catching lizards, early mammals, and insects that larger predators couldn’t be bothered with.

What’s remarkable about Compsognathus is how it dominated its ecological niche so completely. Its lightweight build and powerful legs allowed it to reach speeds of up to 40 mph, making it faster than most modern birds. In the world of small prey, nothing could escape this tiny terror.

Saurophaganax: The Allosaurus Killer

Standing at nearly 43 feet long, Saurophaganax was quite literally the predator that ate other predators. This massive theropod was so large that it likely preyed on other carnivorous dinosaurs, including Allosaurus. Its name literally means “lizard eater,” but perhaps it should have been called “predator eater.”

The sheer size of Saurophaganax meant it had no natural enemies once fully grown. Its massive skull could deliver bone-crushing bites, while its powerful legs allowed it to chase down even the fastest prey. This was apex predation taken to its logical extreme.

Pteranodon: Master of the Skies

While technically from the Cretaceous period, Pteranodon’s Jurassic relatives like Rhamphorhynchus ruled the skies with similar efficiency. These flying reptiles weren’t just scavengers – they were active hunters with wingspans reaching up to 23 feet. Their sharp beaks and excellent eyesight made them perfectly adapted for catching fish from the ocean’s surface.

The aerial advantage gave these pterosaurs access to prey that ground-based predators couldn’t reach. They could spot schools of fish from hundreds of feet above, then dive down at incredible speeds to snatch their meals. In the three-dimensional world of air and sea, they were truly without equal.

Dilophosaurus: The Crested Killer

Don’t let Hollywood fool you – Dilophosaurus wasn’t a tiny poison-spitting lizard. This Early Jurassic predator was actually 23 feet long and built like a precision killing machine. Its distinctive double crest likely served as a display feature, helping individuals recognize their own species and intimidate rivals.

Dilophosaurus had unusually long arms for a large theropod, ending in powerful claws that could grasp and manipulate prey. Its lightweight build suggests it was an active hunter, capable of pursuing prey over long distances rather than relying on ambush tactics like some of its bulkier relatives.

Dakosaurus: The Crocodile That Thought It Was a Shark

Perhaps the most bizarre apex predator of the Jurassic was Dakosaurus, a fully marine crocodile that abandoned its traditional lifestyle for life in the open ocean. This 16-foot-long predator had flippers instead of legs and a shark-like tail fin, making it perfectly adapted for high-speed pursuit of prey.

Dakosaurus represents one of evolution’s most successful experiments in predator design. Its powerful jaws could crush the shells of ammonites and other marine prey, while its streamlined body allowed it to compete directly with sharks and marine reptiles. It was proof that apex predators could adapt to any environment.

The Ecological Impact of Jurassic Apex Predators

The reign of these apex predators shaped the entire Jurassic ecosystem in profound ways. Their presence created evolutionary pressure that drove the development of defensive adaptations in herbivores – from the massive size of sauropods to the armor plating of stegosaurs. Without these predators, the dinosaur world would have looked completely different.

These predators also played a crucial role in maintaining ecological balance. By controlling herbivore populations, they prevented overgrazing and allowed plant communities to flourish. Their hunting behavior even influenced the evolution of social behaviors in prey species, leading to the development of herding instincts and cooperative defense strategies.

The apex predators of the Jurassic period weren’t just random killing machines – they were the architects of an entire ecosystem. From the bone-crushing jaws of Allosaurus to the lightning-fast strikes of Compsognathus, each predator filled a specific ecological niche that helped maintain the delicate balance of prehistoric life. These ancient hunters pushed the boundaries of what was possible in predator design, creating innovations that still inspire modern evolutionary biologists. Their legacy lives on not just in fossil records, but in the very structure of modern ecosystems that still follow patterns established 150 million years ago. What other secrets might these ancient apex predators still be hiding in the rocks beneath our feet?