Picture yourself wandering across an ancient North American landscape where the ground trembles beneath the weight of creatures that would dwarf anything alive today. Imagine glancing up to see a bear standing over ten feet tall on its hind legs, or catching sight of a cat with seven inch fangs slinking through the shadows. This wasn’t some fantasy world. This was your continent not so very long ago.

The Pleistocene megafauna lived on Earth for millions of years and were very important to almost all land-based ecosystems. You would hardly recognize the place if you could step back roughly fifteen thousand years. The air would smell different, the sounds would be alien, and you’d be sharing space with animals so massive and strange that they’d make modern wildlife look downright timid. Extinct giants, such as the American cheetah and ground sloth, lived in North America until they mysteriously died out about 10,000 years ago. What happened to this incredible menagerie remains one of paleontology’s most compelling mysteries, sparking debates that continue to this day. Let’s explore the astonishing creatures that once defined this continent.

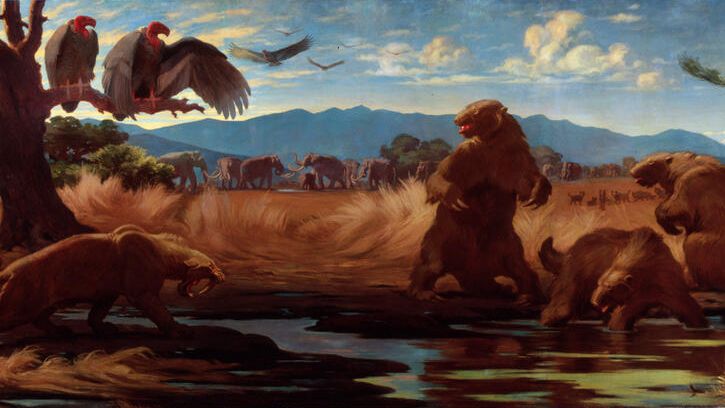

The Giant Short Faced Bear Ruled the Land

The giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) was the largest carnivorous mammal to ever roam North America. Think about that for a moment. Not just big. The biggest carnivorous land mammal on the entire continent, ever. Standing on its hind legs, an adult giant short-faced bear boasted a vertical reach of more than 14 feet. If you encountered one while it reared up, you’d be staring at something nearly three times your height, weighing close to a ton.

What made this bear truly terrifying was its build. The most striking difference between modern North American bears and the giant short-faced bear were its long, lean and muscular legs, which has given rise to the idea that it was a ‘cursorial’ predator, meaning that it ran after prey. Some researchers believe these bears could reach speeds around forty miles per hour. Others think they were more likely scavengers, using their immense size to intimidate other predators off their kills. Either way, you wouldn’t want to run into one on a bad day.

Saber Toothed Cats Were Forest Ambush Specialists

Everyone’s heard of saber toothed tigers, right? Here’s the thing though. They weren’t tigers at all, and recent research reveals they weren’t even hunting where we thought they were. According to analysis of their teeth, the saber-tooth cats of the American West were most likely forest-dwellers that hunted animals such as tapir and deer. For decades, scientists pictured Smilodon fatalis as a plains hunter chasing bison alongside dire wolves.

Turns out that image was wrong. Analyses of hundreds of teeth from La Brea are painting a vastly different picture of this prehistoric terror, which could weigh up to 600 pounds and sported seven-inch-long canine teeth. Those massive fangs weren’t just for show. They were precision instruments designed to deliver killing bites to the throat or neck of prey. The big cats were predators who hunted larger mammals such as mammoths, sloths and bison, killing them most probably by ambushing them and using their famous canines to puncture their prey’s jugular vein or trachea. The saber tooth was a patient stalker, waiting in woodland shadows for the perfect moment to strike.

Dire Wolves Hunted in Massive Packs

If you’re a fan of fantasy epics, you’ve probably heard of dire wolves. The real animals were every bit as formidable as fiction suggests, maybe more so. Like gray wolves, dire wolves hunted in packs of 30 or more and fed on large prey like mammoths, giant sloths and Ice Age horses. Imagine encountering thirty wolves, each one heavier and more powerful than today’s gray wolf, with crushing jaws built for bringing down enormous prey.

Dire wolves, which died out with mammoths and saber-toothed cats at the end of the last ice age, were long thought to be close cousins of gray wolves. Now, the first analysis of dire wolf DNA finds they instead traveled a lonely evolutionary path. They were so genetically distinct that scientists now believe they deserve their own separate classification entirely. These weren’t just big wolves. They were something else altogether, a unique lineage that dominated North America for hundreds of thousands of years before vanishing completely.

Mammoths and Mastodons Shaped the Landscape

The woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) is one of the most famous extinct Ice Age megafauna. Standing 12 feet tall at the shoulders and weighing six to eight tons, the woolly mammoth grazed the northern steppes of Ice Age North America using its colossal, 15-foot curved tusks. You couldn’t miss these giants if you tried. Their presence transformed entire ecosystems, shaping vegetation patterns and creating pathways through dense forests.

The American mastodon (Mammut americanum) is the most ancient of the North American “elephants.” Its ancestors crossed the Bering Strait from Asia roughly 15 million years ago and evolved into the American mastodon 3.5 million years ago. Though similar in appearance to mammoths, mastodons were actually quite different animals with distinct diets and habitats. Nearly all mammoths and mastodons were wiped out in the great megafauna extinction 10,000 years ago, but archeologists have dug up remains showing that lone bands of mammoths still roamed arctic islands as recently as 4,500 years ago. Some mammoths were still alive when the Egyptian pyramids were being built. Let that sink in.

Giant Ground Sloths Were Nothing Like Their Modern Cousins

Today’s sloths are cute, slow moving tree dwellers about the size of a medium dog. Their prehistoric ancestors were anything but small. The giant ground sloths of the late Pleistocene were bear-sized herbivores that stood 12 feet on their hind legs and weighed up to 3,000 pounds. Picture a creature as tall as a basketball hoop, covered in thick fur, with claws nearly a foot long on each massive paw.

One giant sloth species, the Jefferson ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii), was named for Thomas Jefferson, who initially believed that sloth fossils were a type of colossal cat that he dubbed the Megalonyx (“giant claw”). Even founding fathers got it wrong sometimes. These animals were herbivores, feeding on leaves and vegetation, but It’s clear from ground sloths’ skeletal anatomy that they were incapable of running, so when it came to a fight-or-flight encounter with one of the Americas’ many predators (e.g. the infamous sabre-tooth tiger Smilodon), they probably always chose the former. To defend themselves, ground sloths had long, sharp claws on the ends of several of their fingers. You definitely didn’t want to threaten one.

American Lions Were Colossal Predators

The American lion (Panthera atrox) is an extinct pantherine cat native to North America during the Late Pleistocene from around 129,000 to 12,800 years ago. It was about 25% larger than the modern lion, making it one of the largest known felids to ever exist. Think about African lions, already among the most impressive predators alive today. Now add another quarter of their mass and imagine them prowling Ice Age grasslands.

Recent evidence suggests something fascinating about these enormous cats. Her team’s comprehensive study also helps to explain why smaller predators such as coyotes and grey wolves were able to survive to the modern day, while larger carnivores such as saber-tooth cats, dire wolves, and American lions all went extinct 10,000 to 12,000 years ago. The key might have been dietary flexibility. When the large herbivores began disappearing, the massive carnivores couldn’t adapt quickly enough. The most common prey species would have varied considerably across the range of the American lion but may have included camelids, horses, bovids and deer. When those vanished, so did the lions that depended on them.

A Diverse Cast of Supporting Characters

The headline grabbers weren’t the only remarkable animals wandering prehistoric America. You would have encountered bizarre creatures at every turn. Giant beavers the size of modern black bears gnawed through trees along waterways. Enormous armored glyptodonts, relatives of armadillos but built like tanks, trundled across the plains. American cheetahs, faster than anything alive today, streaked across open grasslands in pursuit of pronghorn antelope.

The mosaic vegetation of woods, shrubs, and grasses in southwestern North America supported large herbivores such as horses, bison, antelope, deer, camels, mammoths, mastodons, and ground sloths. Yes, camels. North America had native camels during the Ice Age, along with multiple species of horses that would later go completely extinct on this continent. The sheer diversity of life was staggering, creating ecosystems more varied and complex than anything you’ll see in Africa today. It’s hard to believe we lost so much.

The Great Mystery of Their Disappearance

Overall, during the Late Pleistocene about 65% of all megafaunal species worldwide became extinct, rising to 72% in North America, 83% in South America and 88% in Australia. What caused such a catastrophic loss remains hotly debated among scientists. There are two main hypotheses to explain this extinction: Climate change associated with the advance and retreat of major ice caps or ice sheets causing reduction in favorable habitat. Human hunting causing attrition of megafauna populations, commonly known as “overkill”.

The timing is suspicious. Extinctions in North America were concentrated at the end of the Late Pleistocene, around 13,800–11,400 years Before Present, which were coincident with the onset of the Younger Dryas cooling period, as well as the emergence of the hunter-gatherer Clovis culture. However, recent evidence suggests the story might be more complicated. There was this idea that humans arrived and killed everything off very quickly – what’s called ‘Pleistocene overkill,’ said Daniel Odess, an archaeologist at White Sands National Park in New Mexico. But new discoveries suggest that “humans were existing alongside these animals for at least 10,000 years, without making them go extinct”. Maybe it wasn’t a simple case of humans showing up and wiping everything out. Perhaps climate shifts, human pressure, and ecosystem disruption combined to create a perfect storm of extinction.

What We’ve Lost Cannot Be Recovered

Around 12,700 years ago, North America lost 70 percent of its large mammals – a megafaunal extinction event paleontologists and archaeologists have been arguing over for more than half a century. Think about what that means. Imagine if you woke up tomorrow and seven out of ten large animal species had simply vanished. The ecological devastation would be unimaginable, yet that’s exactly what happened to this continent.

Before this extinction the diversity of large mammals in North America was similar to that of modern Africa. We went from Serengeti level diversity to what we have now in the blink of an evolutionary eye. These giant mammals had important roles for the healthy functioning of ecosystems, like redistributing nutrients through their poop and dispersing seeds. When they disappeared, entire ecological networks collapsed. The landscapes changed. Forests grew differently without mammoths and mastodons clearing pathways. Fire patterns shifted without massive herbivores maintaining grasslands. We’re still living in the shadow of that ancient catastrophe, in ecosystems fundamentally altered by losses we can barely comprehend.

Conclusion

Prehistoric America was a realm of genuine wonders that makes today’s wildlife look tame by comparison. You would have witnessed bears taller than modern giraffes, cats with dagger like fangs longer than your hand, ground dwelling sloths weighing more than compact cars, and wolves hunting in packs large enough to take down elephants. These weren’t mythical beasts from legend. They were real animals that breathed the same air, drank from the same rivers, and walked the same ground you do today, just a geological heartbeat ago in the grand scheme of things.

The extinction of these magnificent creatures remains one of science’s most compelling unsolved mysteries. Whether humans, climate change, or some combination of factors caused their demise, the result is the same. We lost something irreplaceable. The megafauna shaped ecosystems in ways we’re only beginning to understand, and their absence continues to echo through modern landscapes. Next time you walk through a forest or cross a prairie, try imagining what it might have looked like when giants still roamed. What would you have done if you’d encountered a short faced bear or watched a pack of thirty dire wolves hunt across the plains? Did you expect the scale of what we lost?