Picture a scene roughly one hundred million years ago: the late afternoon sun casting long shadows across what would one day become Colorado. But instead of silence, the landscape thrums with activity that would make any modern dating scene look positively boring. This is where our story of prehistoric romance begins, in a world where love required far more than just a good pickup line.

The Dinosaur Dance Floor That Time Forgot

About 100 million years ago, 23 kilometers west of what is today Denver, large groups of male theropod dinosaurs gathered to dance, twisting and kicking in what may have been one of the most elaborate mating rituals in the ancient world, and using high-resolution drone photography and 3D modeling at Dinosaur Ridge near Denver, the team identified dozens of clustered scrape marks in the sandstone – a prehistoric “dance floor” etched into the earth more than 100 million years ago. What paleontologists discovered there reads like something out of a prehistoric romantic comedy. These ancient casanovas didn’t just show up and hope for the best.

These traces were generated by backward kicking movements repeated by both the left and right foot, and some of the impressions suggest the dinosaurs turned clockwise as they scraped their claws through the sand, indicating a unique, repetitious dance. Think of it like nature’s original breakdancing competition, except the stakes were survival of the species rather than street cred.

The Prehistoric Moonwalk That Would Make Michael Jackson Jealous

We can tell they had two moves so far, one walking backwards and one moving side to side, and if they were really excited, they would step a few feet backward and repeat the motion, which usually erases the back half of each earlier set of scrapes. When this happened 3 or more times, a few of these show a counter-clockwise turn, kind of like the moonwalk with a little spin. These weren’t just random movements either.

Some appeared to have been made by the creatures kicking their feet backward one at a time, while others seem to have come from individuals rotating and scraping their claws on the ground, indicating a counterclockwise or a clockwise turn, and it’s kind of like the moonwalk with a little spin. The precision and repetition suggest these moves were as choreographed as any modern mating display. Imagine a two-ton predator carefully executing dance steps that would put most wedding reception performances to shame.

When Size Mattered: The Ultimate Prehistoric Pickup Arena

The new discovery suggests the site is a large mating display arena, also called a lek, rather than a small nesting area as previously believed, and in these leks, groups of male birds gather together and kick up sediments in an attempt to entice female spectators. But this wasn’t just any old gathering spot. Scientists have identified what might be the largest prehistoric dating ground ever discovered.

To go from two to potentially three lek traces to having more than 30 in this study could make our site the largest lekking arena in the world. Picture a massive prehistoric convention center where dozens of hopeful suitors competed for attention, each trying to outdo the others with increasingly elaborate performances. The competition must have been fierce, with prime real estate going to the most impressive dancers.

The Sound of Prehistoric Seduction

But dancing wasn’t the only weapon in the dinosaur dating arsenal. As expected, based on the structure of the crest, the dinosaur apparently emitted a resonating low-frequency rumbling sound that can change in pitch. Each Parasaurolophus probably had a voice that was distinctive enough to distinguish it not only from other dinosaurs, but also from other Parasaurolophuses. These weren’t just random noises either.

This prehistoric basso profundo was equipped with a rich vibrato and could vary the pitch. The digital paleontologists believe Parasaurolophus probably had a voice that was distinctive enough to distinguish it from other individuals, and the sound may have been somewhat birdlike, and it’s probably not unreasonable to think they did songs of some sort to call one another. Imagine prehistoric love ballads echoing across ancient landscapes, each singer trying to hit just the right note to win over their desired mate.

Musical Instruments Built Into Their Heads

Parasaurolophus, with its dramatic backward-curving hollow crest measuring up to 6 feet long, has been particularly well-studied; computer models suggest these structures could have produced deep, trombone-like sounds when air passed through them, and computer simulations based on CT scans of fossil skulls suggest these dinosaurs could have produced resonant, low-frequency sounds similar to those of brass instruments. These weren’t simple tools but sophisticated biological instruments.

Not only are there more tubes than the simple, trombone-like loops described in previous studies, but there are new chambers within the crest, and once the size and shape of the air passages were determined with the aid of powerful computers and unique software, it was possible to determine the natural frequency of the sound waves the dinosaur pumped out, much the same as the size and shape of a musical instrument governs its pitch and tone. Nature had crafted walking symphonies, each with their own unique acoustic signature.

Fashion Statements Written in Feathers and Bone

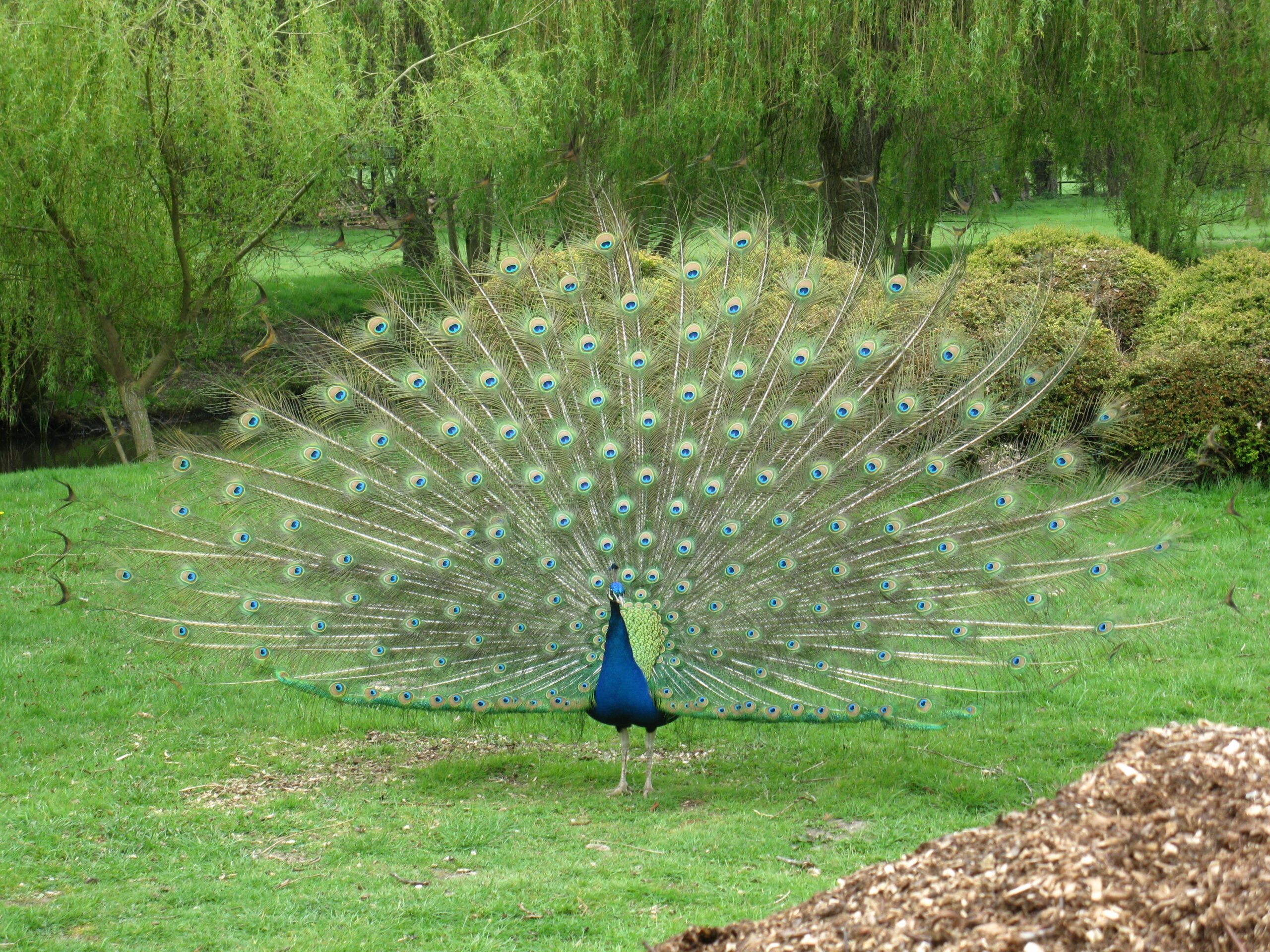

While these larger dinosaurs couldn’t fly, they likely used their primitive plumage for insulation or visual displays, the same way modern peacocks attract mates. And fossil evidence shows that feathered dinosaurs probably came in a rainbow of colors. If we can have pink flamingos, we could have pink feathered dinosaurs as well. The prehistoric world was apparently much more colorful than Hollywood ever imagined.

Work in the past decade on the cells that contain color pigments in the exquisitely preserved fossils of feathered dinosaurs have revealed that some dinosaurs were brightly colored – perhaps surprisingly so, given how popular culture historically portrayed them as grayish green. Picture strutting dinosaurs decked out in iridescent blues, shocking reds, and brilliant golds, all competing to catch the eye of their intended mate.

The Original Battle of the Sexes

If we look at the lek in comparison with modern birds, it implies a strong level of sexual dimorphism between males and females. Males of lekking species such as the Sage-Grouse and Birds-of-paradise often have colourful and intricate feather patterns designed to enhance their display. The prehistoric dating game was clearly dominated by the males putting on spectacular shows.

Plumage dimorphism, in the form of ornamentation or coloration, also varies, though males are typically the more ornamented or brightly colored sex. Such differences have been attributed to the unequal reproductive contributions of the sexes. The evidence suggests that male dinosaurs were the peacocks of their era, sporting the flashiest colors and most elaborate ornaments to win female approval.

Horns, Frills, and Other Prehistoric Bling

The large bony frill that skirts the skull of Protoceratops dinosaurs, part of the same family as Triceratops, is also thought to be used as a signal to prospective mates, a recent study of 30 complete skulls suggested. It’s not a feature found in living animals today, and paleontologists have long debated what the function was of the diverse array of frills and horns in ceratopsians. These weren’t just defensive weapons but prehistoric jewelry designed to impress.

Several dinosaur species had horns and spikes in arrangements that would not have been very helpful for defense. Instead, paleontologists suggest they might have served to impress mates – and some species might have had showy feathers for that purpose, too. Imagine Triceratops as the equivalent of a punk rocker, using their impressive headgear not to intimidate enemies but to show off their genetic fitness to potential partners.

The Science Behind Prehistoric Passion

In addition to scrape displays, dinosaurs potentially used vocalizations and visual displays as part of their courtship rituals. Similar to modern birds, these elaborate mating dances, vocalizations, and displays would have contributed to the energetic and visually striking courtship behaviors of dinosaurs. The sheer complexity of these behaviors suggests that dinosaur social lives were far more sophisticated than previously imagined.

Sexual dimorphism – sex-specific differences in morphology and appearance – can be observed in many animals and is most obvious when it involves external and soft-tissue features, such as reproductive organs or brightly coloured feathers. In many cases, these features are accompanied by corresponding variations in the skeleton which can be subtle, but still sufficient to confidently tell the sexes apart. The fossil evidence is painting a picture of creatures whose entire anatomy was shaped by the need to find and attract mates.

When Dinosaurs Gathered to Party

During mating season, one could imagine dozens of Parasaurolophus calling to each other, much like living alligators and crocodiles do today. The Late Cretaceous certainly would have been a very noisy place. These weren’t quiet, private affairs but massive social gatherings that would have dominated the prehistoric landscape.

This shows a concentration of probably male dinosaurs in a very small area doing their displays, both for territory and also to attract a mate. The females would be able to congregate in a central location around them, so that they would be able to prove dominance and have mate selection somewhat simultaneously. Think of it as the ultimate prehistoric speed dating event, where dozens of suitors competed simultaneously while potential mates had their pick of the crowd.

The Love That Lasted Millions of Years

What makes these discoveries truly remarkable isn’t just what they tell us about individual species, but what they reveal about the continuity of life itself. It also suggests that some mating rituals date back tens of millions of years and could be part of a deep evolutionary connection between dinosaurs and modern birds. The elaborate courtship displays we see in today’s birds aren’t recent evolutionary innovations but ancient traditions that stretch back to the age of dinosaurs.

In fact, evidence of courtship in the fossil record could appear much more frequently than direct evidence of mating. Considering that not all courtships successfully result in mating, and the potentially large number of moves a suitor might perform, courtship traces should be far more common than remains of the suitor. Every scrape mark and dance floor preserved in stone represents countless individual moments of prehistoric romance, most of which ended in rejection rather than reproduction.

The story of dinosaur courtship reminds us that some things never change. The desire to impress, to stand out from the crowd, and to find that special someone has been driving evolution for hundreds of millions of years. Whether it’s a two-ton theropod executing perfect dance moves or a crested hadrosaur singing prehistoric love songs, the fundamental drive to connect remains one of life’s most powerful forces.

When you hear a bird singing at dawn or watch peacocks strutting their stuff at the zoo, remember that you’re witnessing the continuation of a love story that began long before humans walked the earth. In the end, perhaps the most romantic thing about dinosaur courtship isn’t the elaborate displays or prehistoric serenades – it’s the fact that love found a way to survive extinction itself, carried forward in the songs and dances of their feathered descendants. What other prehistoric secrets might still be waiting to be discovered in the rocks beneath our feet?