Picture this: a world where the ground trembles beneath the feet of massive sauropods, where pterosaurs soar through steamy skies, and where death comes on swift legs adorned with razor-sharp claws. Welcome to the Late Cretaceous period, roughly 100 to 66 million years ago, when some of Earth’s most terrifying yet elegant predators ruled the ancient landscapes. These weren’t just any dinosaurs – they were dromaeosaurs, the “raptor” family that has captured our imagination like no other prehistoric creature. But here’s what might shock you: these lethal hunters were covered in feathers, transforming our understanding of what dinosaurs actually looked like and how they lived.

The Feathered Assassins That Changed Everything

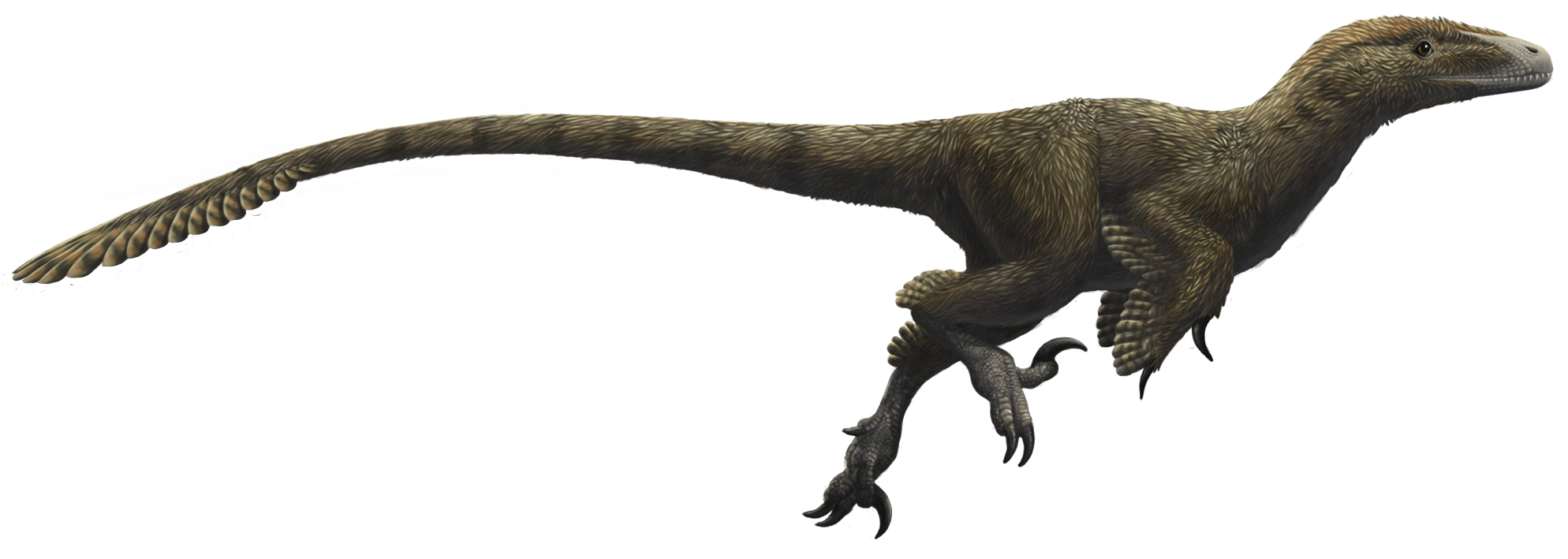

When paleontologists first discovered fossilized evidence of feathers on dromaeosaurs, it sent shockwaves through the scientific community. These discoveries, particularly from specimens like Microraptor and Sinornithosaurus, revealed that raptors weren’t the scaly, lizard-like creatures we’d imagined for decades. Instead, they were adorned with complex feather structures that likely served multiple purposes beyond just insulation.

The feathers on these predators weren’t just simple fuzz either. Many species displayed intricate plumage that could have been used for display, camouflage, or even primitive flight capabilities. Some researchers believe that certain raptor species may have used their feathered arms to create shadows while hunting, similar to how modern herons use their wings to reduce glare when fishing.

Velociraptor: The Mongolian Speed Demon

Perhaps no dinosaur has captured popular imagination quite like Velociraptor, though the real animal was far different from its Hollywood portrayal. These Mongolian predators stood about knee-high to an adult human, roughly the size of a large dog, but what they lacked in stature they made up for in pure lethality. Their name literally means “swift thief,” and fossil evidence suggests they were indeed incredibly fast runners.

Velociraptor’s most distinctive feature was its sickle-shaped killing claw on each foot, which could extend up to 2.6 inches in length. Recent studies suggest these claws weren’t used for slashing as often depicted in movies, but rather for puncturing and holding onto prey while the raptor used its powerful jaws to deliver the killing bite. The famous “Fighting Dinosaurs” fossil from Mongolia shows a Velociraptor locked in mortal combat with a Protoceratops, providing a frozen snapshot of ancient predator-prey dynamics.

Deinonychus: The Terrible Claw That Sparked a Revolution

Before Deinonychus burst onto the paleontological scene in 1964, dinosaurs were viewed as sluggish, cold-blooded reptiles destined for extinction. This North American raptor, whose name means “terrible claw,” completely revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur behavior and physiology. Standing about 3 feet tall and measuring 11 feet in length, Deinonychus was significantly larger than its Mongolian cousin Velociraptor.

What made Deinonychus truly revolutionary wasn’t just its size, but the evidence it provided for warm-blooded, highly active dinosaurs. Its bone structure, muscle attachments, and overall anatomy suggested an animal capable of sustained high-energy activity. The discovery of multiple Deinonychus specimens near a single Tenontosaurus skeleton led paleontologists to hypothesize that these raptors may have hunted in coordinated packs.

The famous paleontologist John Ostrom, who first described Deinonychus, noted that the dinosaur’s anatomy was more bird-like than reptilian, helping to establish the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and modern birds.

Utahraptor: The Giant That Defied Expectations

Just when paleontologists thought they had raptors figured out, along came Utahraptor to shatter all expectations. This massive predator from Early Cretaceous Utah was a true giant among dromaeosaurs, measuring up to 23 feet in length and weighing as much as 1,500 pounds. Its killing claws were absolutely monstrous, reaching up to 15 inches in length – longer than a chef’s knife.

Utahraptor’s discovery proved that the raptor body plan could be scaled up to massive proportions while maintaining its deadly efficiency. Unlike its smaller relatives, this giant likely hunted alone or in very small groups, targeting large prey like iguanodonts and even smaller sauropods. The sheer size of Utahraptor’s claws suggests it may have been capable of bringing down prey much larger than itself.

Recent discoveries in Utah have revealed what appears to be a Utahraptor family group preserved in quicksand, providing tantalizing glimpses into the social behavior of these apex predators.

Microraptor: The Four-Winged Wonder

Perhaps no dinosaur has provided more insight into the evolution of flight than Microraptor, a crow-sized raptor from Early Cretaceous China. This remarkable creature possessed feathers not just on its arms, but also on its legs, creating a four-winged configuration that has fascinated researchers for decades. The iridescent black feathers preserved in some specimens suggest these dinosaurs may have been as colorful as modern birds.

Microraptor couldn’t achieve powered flight like modern birds, but it was likely an accomplished glider, using its four wings to move between trees in dense forest environments. Computer models suggest it could glide distances of up to 130 feet, making it a highly mobile predator in its arboreal habitat. Its diet consisted mainly of small mammals, birds, and fish, making it one of the most ecologically diverse raptors known.

The discovery of Microraptor has provided crucial evidence for the “trees-down” theory of flight evolution, suggesting that powered flight evolved from gliding ancestors rather than from ground-running dinosaurs.

Dakotaraptor: The Late Cretaceous Giant

Discovered in South Dakota’s Hell Creek Formation, Dakotaraptor represents one of the largest known raptors from the very end of the Cretaceous period. This 17-foot-long predator lived alongside Tyrannosaurus rex and Triceratops, proving that large dromaeosaurs survived right up until the mass extinction event. Its discovery was particularly significant because it filled a notable gap in the North American raptor fossil record.

Dakotaraptor possessed the characteristic sickle claw of its family, measuring over 9 inches in length. What made this discovery even more remarkable was the presence of quill knobs on its arm bones, providing direct evidence that even giant raptors retained feathered wings. These features suggest that Dakotaraptor may have used its feathered arms for display, thermoregulation, or possibly even limited gliding capabilities despite its large size.

The presence of such a large raptor in the Hell Creek ecosystem demonstrates the incredible diversity of predators that existed in the final chapter of the Mesozoic Era.

Austroraptor: The Long-Snouted Enigma

From the windswept plains of Argentina comes Austroraptor, a raptor that challenged traditional ideas about dromaeosaur anatomy and behavior. This 16-foot-long predator possessed an unusually long, narrow snout filled with small, conical teeth – features more reminiscent of a crocodile than a typical raptor. Its proportionally small arms and reduced flight feathers suggested a lifestyle quite different from its more famous relatives.

Austroraptor’s unique anatomy indicates it may have been specialized for hunting fish and other aquatic prey, using its elongated snout to snatch prey from water bodies. This ecological niche would have been similar to that occupied by modern herons or crocodilians. The discovery of Austroraptor demonstrated that raptors had diversified into a wide range of ecological roles by the Late Cretaceous.

Its relatively small arms and reduced feathering also provide insights into how flight-related features were lost in some lineages as they adapted to different lifestyles and environments.

Zhenyuanlong: The Winged Dragon of China

China’s Liaoning Province has yielded numerous feathered dinosaur discoveries, but few have been as visually striking as Zhenyuanlong, whose name means “Zhenyuan’s dragon.” This raptor, measuring about 6 feet in length, possessed some of the most elaborate wing feathers ever discovered on a non-flying dinosaur. Its arms were adorned with large, modern-style flight feathers arranged in a pattern remarkably similar to those of contemporary birds.

Despite its impressive plumage, Zhenyuanlong was likely flightless due to its body size and proportions. However, the presence of such well-developed feathers suggests these structures served important functions beyond flight preparation. They may have been used for display during mating rituals, for brooding eggs, or for intimidating rivals and prey.

The exquisite preservation of Zhenyuanlong’s feathers has provided paleontologists with unprecedented detail about the structure and arrangement of dinosaur plumage, offering new insights into the evolution of complex feather types.

Balaur: The Double-Clawed Assassin

From the ancient island of Hateg in Romania comes one of the most unusual raptors ever discovered: Balaur bondoc. This stocky predator possessed a unique double-clawed arrangement on each foot, with both the first and second toes equipped with large, sickle-shaped talons. This bizarre configuration made Balaur a particularly formidable predator in its island ecosystem.

Living on an island during the Late Cretaceous, Balaur evolved in isolation and developed several unusual characteristics. Its robust build and powerful legs suggest it was more of an ambush predator than a pursuit hunter, using its double claws to deliver devastating attacks to prey. The island environment may have favored these more heavily armed predators as they competed for limited resources.

Balaur’s discovery highlighted how island environments can drive evolution in unexpected directions, producing creatures that seem almost alien compared to their mainland relatives.

Achillobator: The Mongolian Giant

Mongolia’s Gobi Desert has yielded another impressive raptor in the form of Achillobator, a large dromaeosaur that lived during the Late Cretaceous period. Named after the Greek hero Achilles, this predator measured approximately 20 feet in length and possessed proportionally longer legs than most other large raptors. Its build suggests it was an accomplished runner, capable of pursuing prey across the open landscapes of ancient Mongolia.

Achillobator’s skull was particularly robust, with powerful jaw muscles that would have generated tremendous bite force. Combined with its large size and impressive speed, this made it one of the most formidable predators of its time and place. Fossil evidence suggests it may have hunted the large hadrosaurid dinosaurs that were common in its ecosystem.

The discovery of Achillobator helped paleontologists understand how raptors adapted to different environments and prey types, with this species representing a more cursorial (running) adaptation compared to its more generalized relatives.

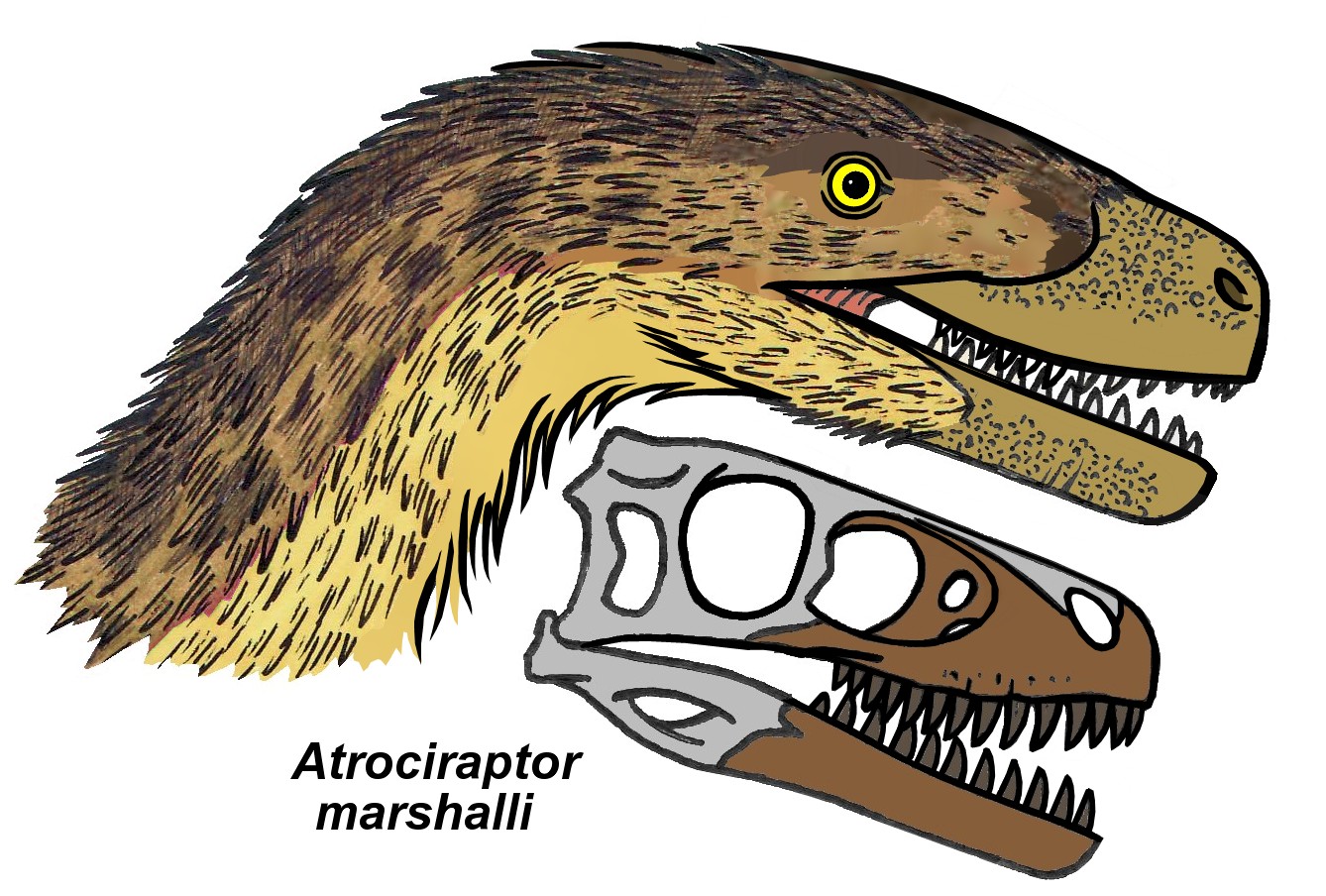

Atrociraptor: The Savage Thief

Canada’s Horseshoe Canyon Formation has produced numerous dinosaur fossils, but few as intriguing as Atrociraptor marshalli. This medium-sized raptor, whose name literally means “savage thief,” possessed a particularly robust skull with a deep, powerful snout. Its teeth were more robust than those of many other raptors, suggesting it may have been capable of crushing bone or dealing with particularly tough prey.

Atrociraptor lived during the very end of the Cretaceous period, making it one of the last raptors to walk the Earth before the mass extinction event. Its presence in the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, alongside other iconic dinosaurs like Albertosaurus and Edmontosaurus, demonstrates that raptors remained important predators right up until the end of the Mesozoic Era.

The robust nature of Atrociraptor’s skull and teeth suggests it may have occupied a slightly different ecological niche than its more gracile relatives, possibly specializing in different types of prey or employing different hunting strategies.

Pyroraptor: The Fire Thief of France

From the sun-baked rocks of southern France comes Pyroraptor olympius, a raptor whose name reflects both its fiery discovery circumstances and its Olympic-sized hunting prowess. This European predator was discovered in rocks that had been burned by forest fires, leading to its dramatic name meaning “fire thief.” Pyroraptor lived during the Late Cretaceous and represents one of the best-known European members of the dromaeosaur family.

What makes Pyroraptor particularly interesting is its geographic location and the insights it provides into European dinosaur ecosystems. During the Late Cretaceous, Europe was largely an archipelago of islands, and Pyroraptor was one of the top predators in this island-dominated environment. Its relatively small size compared to some mainland raptors may reflect the evolutionary pressures of island living.

Recent studies have suggested that Pyroraptor, like many other raptors, was likely covered in feathers and may have possessed colorful plumage for display purposes, adding yet another layer to our understanding of these remarkable predators.

Saurornitholestes: The Lizard Bird Thief

Canada’s Dinosaur Park Formation has yielded numerous raptor specimens, but one of the most intriguing is Saurornitholestes langstoni, whose name means “lizard bird thief.” This medium-sized predator possessed a particularly bird-like skull and may represent an important link in understanding the evolution from dinosaurs to birds. Its lightweight build and relatively large brain suggest it was an intelligent and agile hunter.

Saurornitholestes lived in the lush, subtropical environments of Late Cretaceous Alberta, where it likely hunted small to medium-sized dinosaurs, mammals, and other prey. Its teeth were relatively small and sharp, suggesting it may have specialized in smaller prey items compared to some of its more robust relatives. The discovery of multiple specimens has provided valuable insights into raptor anatomy and behavior.

What makes Saurornitholestes particularly significant is its potential role in understanding the transition from non-avian dinosaurs to birds, with its anatomy showing numerous bird-like characteristics that help illuminate this crucial evolutionary transition.

The Hunting Strategies That Made Them Apex Predators

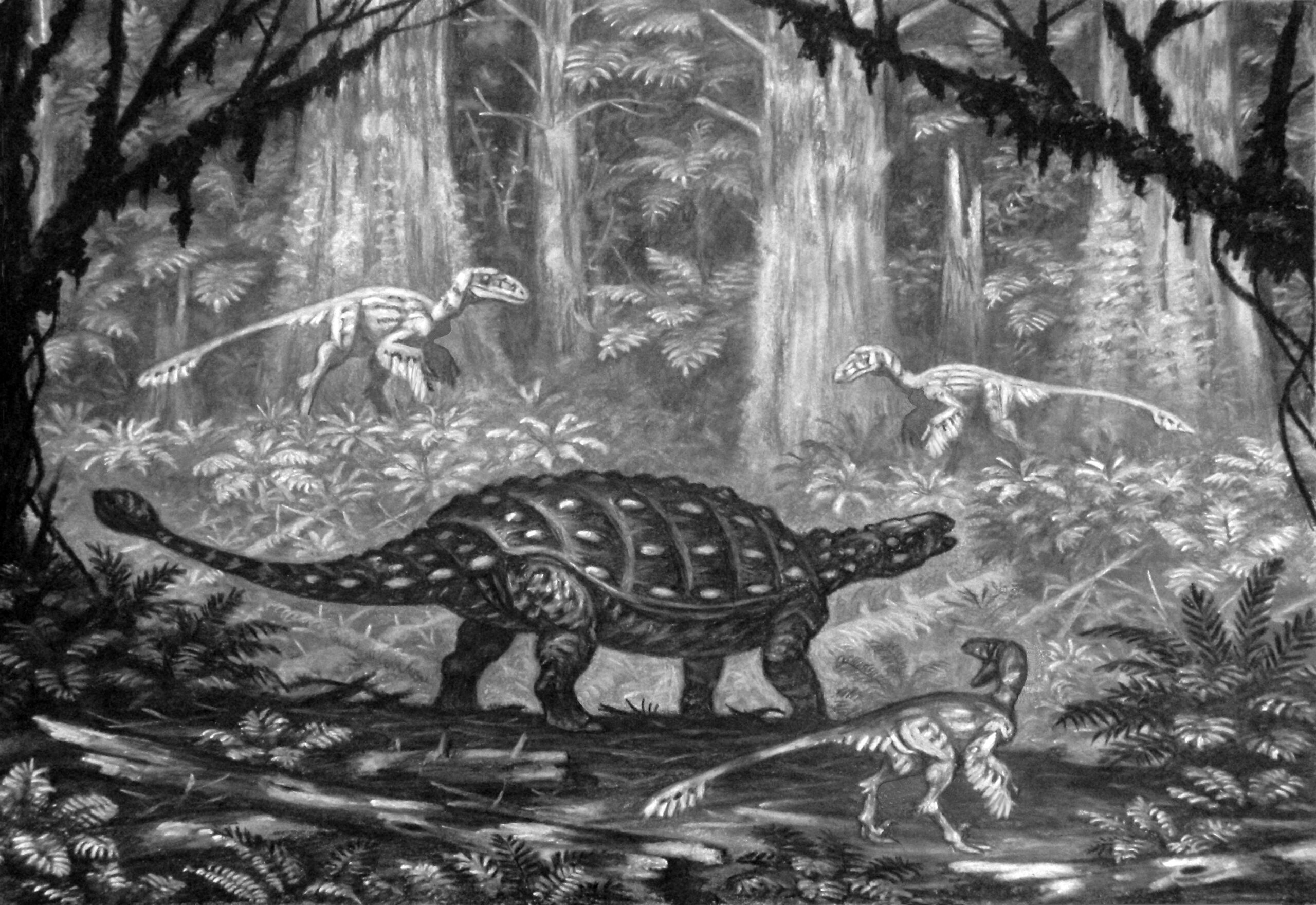

The success of dromaeosaurs as predators wasn’t just due to their famous sickle claws and feathers – it was their sophisticated hunting strategies that made them truly formidable. Recent research has revealed that these dinosaurs employed a variety of techniques depending on their size, prey, and environment. Smaller raptors like Microraptor likely relied on stealth and surprise, dropping from trees onto unsuspecting prey, while larger species like Utahraptor may have used their massive claws to inflict devastating wounds on large herbivores.

Pack hunting behavior, long debated among paleontologists, now has support from several fossil discoveries. The presence of multiple Deinonychus specimens around single prey animals suggests coordinated attacks, while trackway evidence from other sites indicates that some raptors may have hunted in family groups. However, not all raptors were pack hunters – the largest species likely hunted alone due to their enormous energy requirements.

Modern studies of raptor biomechanics have revealed that their famous sickle claws were primarily used for gripping and puncturing rather than slashing, contrary to popular depictions. This “raptor prey restraint” model suggests these predators would leap onto their prey, secure themselves with their claws, and then use their powerful jaws to deliver the killing bite.

The Extinction That Ended an Era

The story of the Late Cretaceous raptors came to an abrupt end 66 million years ago when the Chicxulub asteroid impact triggered a mass extinction event that wiped out all non-avian dinosaurs. However, the legacy of these feathered predators lives on in their direct descendants – modern birds. The evolutionary line that produced raptors also gave rise to the birds that fill our skies today, making every sparrow and eagle a living testament to the success of the dromaeosaur body plan.

The extinction of large raptors created ecological opportunities that were eventually filled by mammalian predators, but none have quite matched the unique combination of intelligence, speed, and lethality that characterized the dromaeosaurs. Their disappearance marked the end of one of evolution’s most successful predatory experiments, leaving behind only fossils and their feathered descendants to remind us of their former glory.

Yet their influence on our understanding of evolution, behavior, and the history of life on Earth continues to grow with each new discovery, ensuring that these magnificent predators will never truly be extinct as long as we continue to study and appreciate their remarkable legacy.

The Late Cretaceous raptors represent one of evolution’s greatest success stories – a family of predators that dominated ecosystems across the globe for millions of years through their perfect combination of intelligence, agility, and specialized hunting adaptations. From the tiny, four-winged Microraptor gliding through ancient forests to the massive Utahraptor stalking across prehistoric plains, these feathered assassins showcase the incredible diversity that can emerge from a single evolutionary innovation. Their discoveries have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaurs, revealing them not as sluggish reptiles but as dynamic, warm-blooded animals more closely related to birds than to any living reptile. As we continue to uncover new species and learn more about their behavior, social structures, and ecological roles, these remarkable predators remind us that the prehistoric world was far more complex and fascinating than we ever imagined. What other secrets might these feathered dragons still be hiding in the rocks beneath our feet?