Picture this: you’re snorkeling in crystal-clear waters when suddenly, a shadow passes overhead. Not a boat or a whale, but something far more extraordinary—a creature the size of a school bus with flippers like airplane wings and eyes as large as dinner plates. This isn’t science fiction; this was reality 200 million years ago when Earth’s oceans teemed with some of the most magnificent predators ever to grace our planet.

The Ocean’s Ancient Rulers

Long before sharks claimed dominance over the seas, massive marine reptiles ruled the ancient oceans with an authority that would make today’s apex predators seem like minnows. These weren’t dinosaurs—they were something entirely different, yet equally spectacular. The Mesozoic Era transformed our planet’s waters into a battleground where titans clashed beneath the waves.

These marine giants evolved from land-dwelling reptiles that ventured back into the ocean, undergoing one of evolution’s most dramatic transformations. Unlike their terrestrial cousins, these creatures developed streamlined bodies, powerful flippers, and hunting strategies that would make them the undisputed masters of their aquatic domain. Their reign lasted over 150 million years, far longer than humans have existed on Earth.

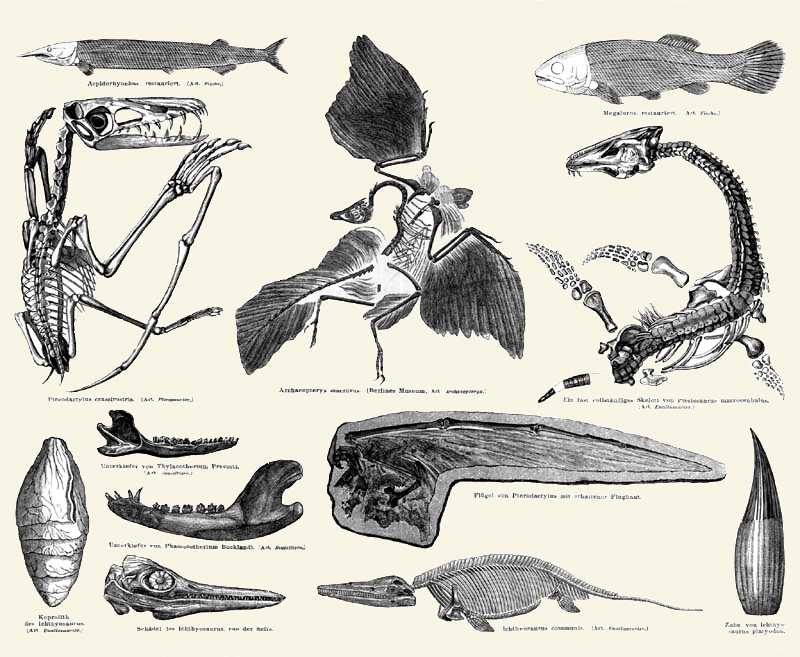

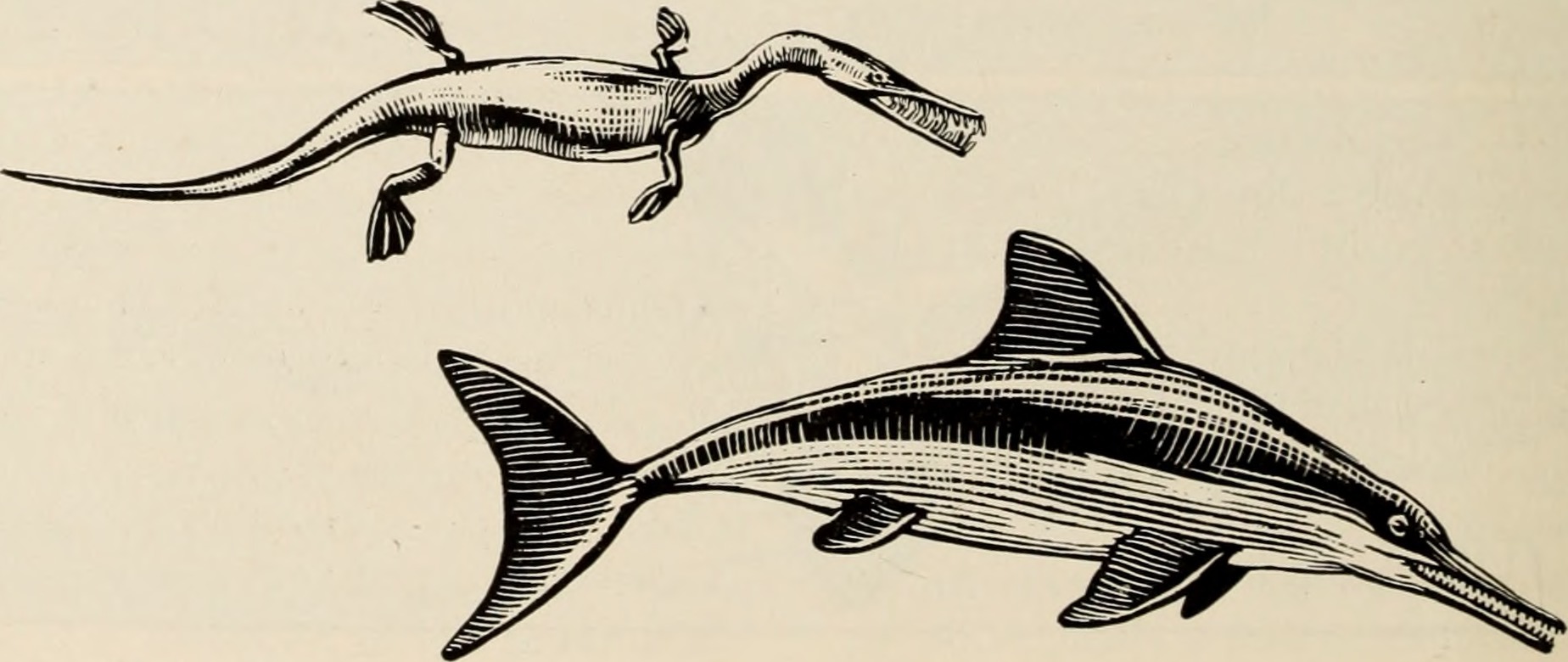

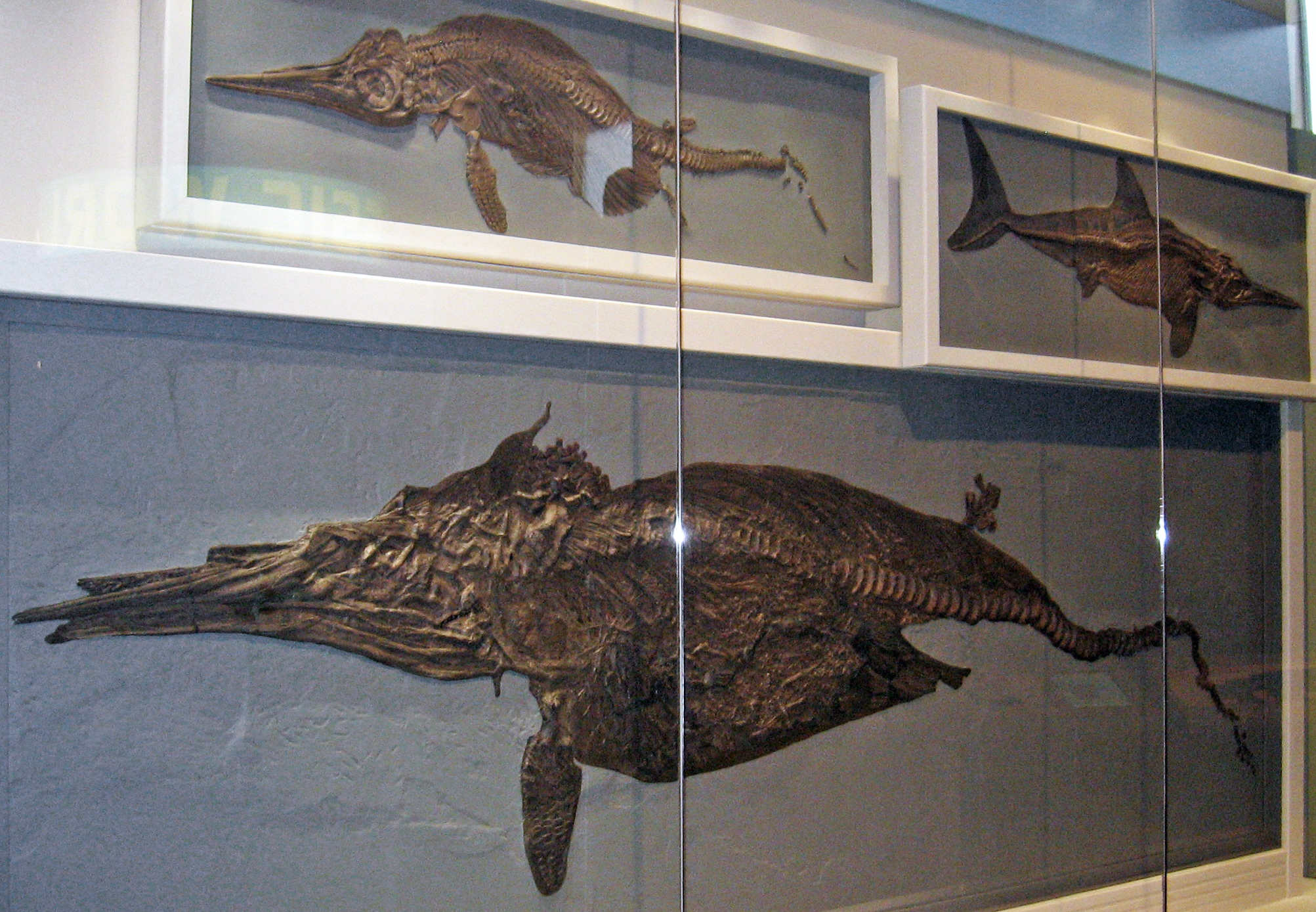

Ichthyosaurs: The Dolphin Mimics

Imagine a dolphin, but stretch it to the length of a sperm whale and give it teeth like railroad spikes. That’s essentially what an ichthyosaur looked like, though they evolved this body plan completely independently from modern marine mammals. These reptilian speedsters represent one of nature’s most stunning examples of convergent evolution—when unrelated animals develop similar features to solve the same environmental challenges.

The largest ichthyosaur ever discovered, Shastasaurus, measured up to 69 feet long, making it longer than most modern whales. These gentle giants likely fed on squid and smaller fish, using their massive size to access deep ocean hunting grounds. Their fossils reveal they gave birth to live young, tail-first like modern whales, showing just how perfectly adapted they were to life in the water.

What made ichthyosaurs truly remarkable was their speed and agility. Fossil evidence suggests they could reach speeds of up to 25 mph, faster than most modern sharks. Their large eyes, some over 10 inches across, allowed them to hunt in the dark depths where sunlight never penetrates.

Pliosaurs: The Ultimate Predators

If ichthyosaurs were the dolphins of the ancient seas, pliosaurs were the killer whales—but with a bite force that would make a T. rex envious. These short-necked marine reptiles possessed skulls that could reach 10 feet in length, packed with teeth designed for crushing rather than slicing. The most famous pliosaur, Leedsichthys, was nicknamed “Predator X” before scientists gave it a proper name.

Pliosaurs like Pliosaurus and Liopleurodon were the apex predators of their time, with bite forces estimated at over 33,000 pounds per square inch. To put that in perspective, that’s more than four times stronger than a T. rex and twelve times stronger than a modern great white shark. These monsters didn’t just hunt fish—they hunted other marine reptiles, including smaller pliosaurs and long-necked plesiosaurs.

Their hunting strategy was brutal efficiency. Unlike the pursuit predation of ichthyosaurs, pliosaurs were ambush hunters, using their massive flippers to generate sudden bursts of speed. They would lie in wait, then explode upward to catch prey in their devastating jaws.

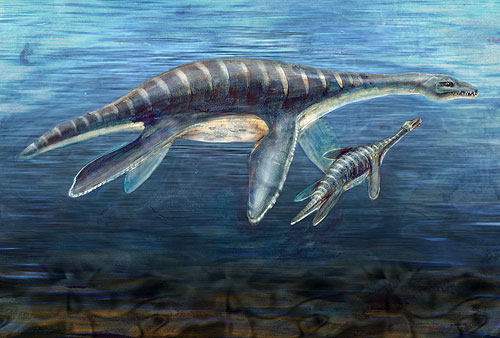

Plesiosaurs: The Loch Ness Legends

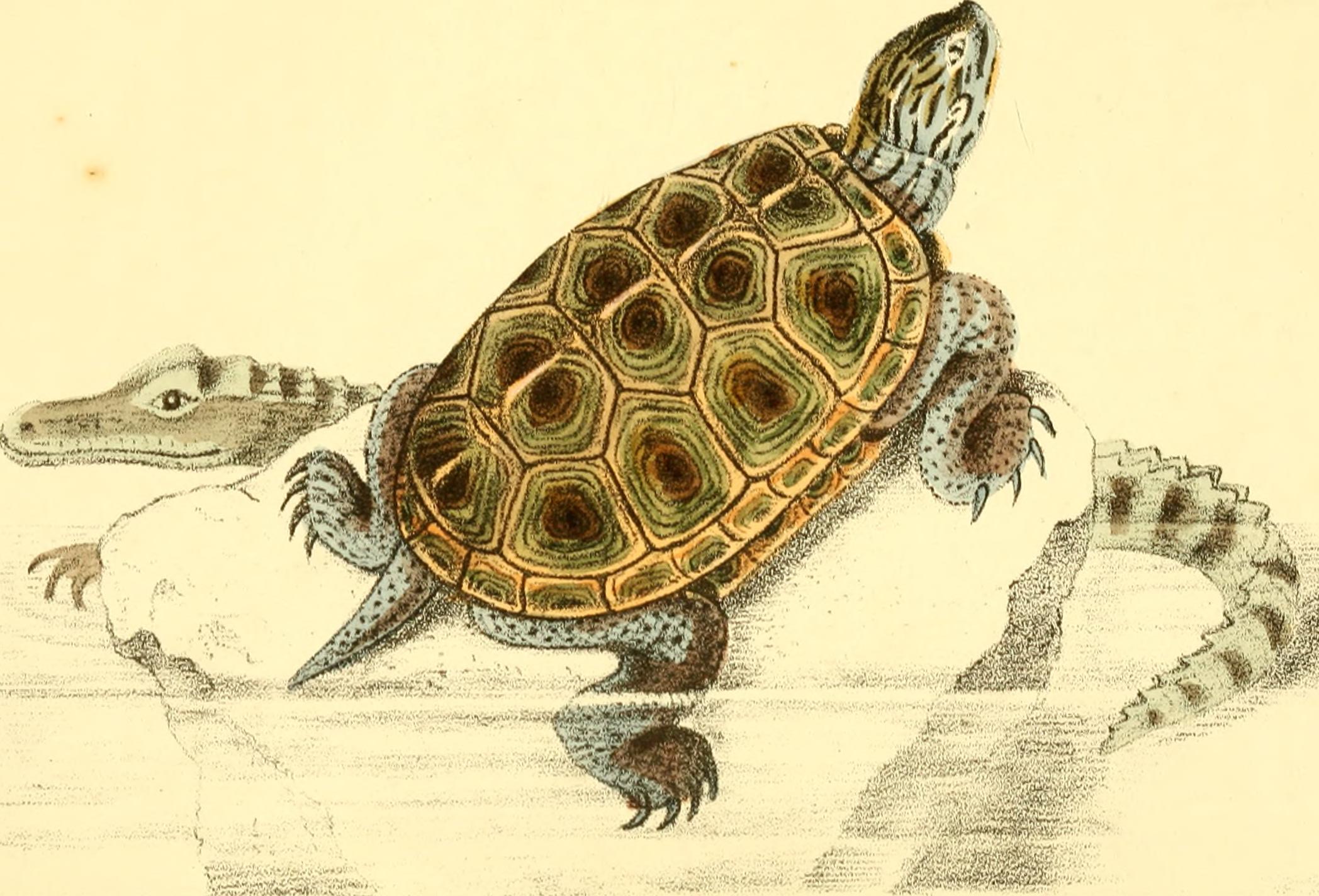

With necks longer than a giraffe’s and bodies like massive sea turtles, plesiosaurs are perhaps the most recognizable of all marine reptiles. These are the creatures that inspired countless sea monster legends, including the famous Loch Ness Monster. Their unique body plan—small head, extremely long neck, barrel-shaped body, and four large flippers—made them unlike anything alive today.

The longest-necked plesiosaur, Elasmosaurus, had a neck containing 72 vertebrae, making it longer than the rest of its body. This incredible adaptation allowed them to strike like a snake, shooting their small heads forward to snatch unsuspecting fish. Their necks were so flexible they could literally tie themselves in knots, though they probably never needed to.

Recent research suggests these gentle giants used their long necks for more than just hunting. They may have used them for breathing at the surface while their bodies remained submerged, similar to how modern snorkelers use breathing tubes. This would have made them incredibly energy-efficient swimmers.

Mosasaurs: The Late Arrivals

Just when you thought the oceans couldn’t get any more dangerous, along came the mosasaurs—massive marine lizards that appeared relatively late in the Mesozoic Era but quickly became the new kings of the sea. These weren’t evolved from earlier marine reptiles; they were monitor lizards that took to the water and grew to monstrous proportions.

Tylosaurus, one of the largest mosasaurs, stretched up to 50 feet long and possessed a skull alone that measured 6 feet. Unlike other marine reptiles, mosasaurs retained their lizard-like appearance but adapted it for marine life. Their tails became powerful propulsion systems, and their limbs transformed into efficient flippers.

What made mosasaurs particularly fearsome was their opportunistic hunting style. They ate everything—fish, other marine reptiles, ammonites, and even small plesiosaurs. Fossil evidence shows they were capable of taking down prey almost as large as themselves, making them the ultimate ocean bullies of the Late Cretaceous period.

Prehistoric Ocean Food Chains

The ancient oceans weren’t just home to these giants—they supported complex ecosystems that would make modern marine biologists weep with envy. Ammonites, those spiral-shelled cephalopods, filled the niche occupied by modern squid and octopuses but grew to incredible sizes. Some ammonites reached 6 feet across, providing substantial meals for hungry marine reptiles.

Belemnites, relatives of modern squid, swarmed the seas in vast numbers, their bullet-shaped internal shells now common fossils. These creatures formed the base of many food chains, supporting not just the marine reptiles but also marine crocodiles, early sharks, and primitive bony fish that were experimenting with new forms and sizes.

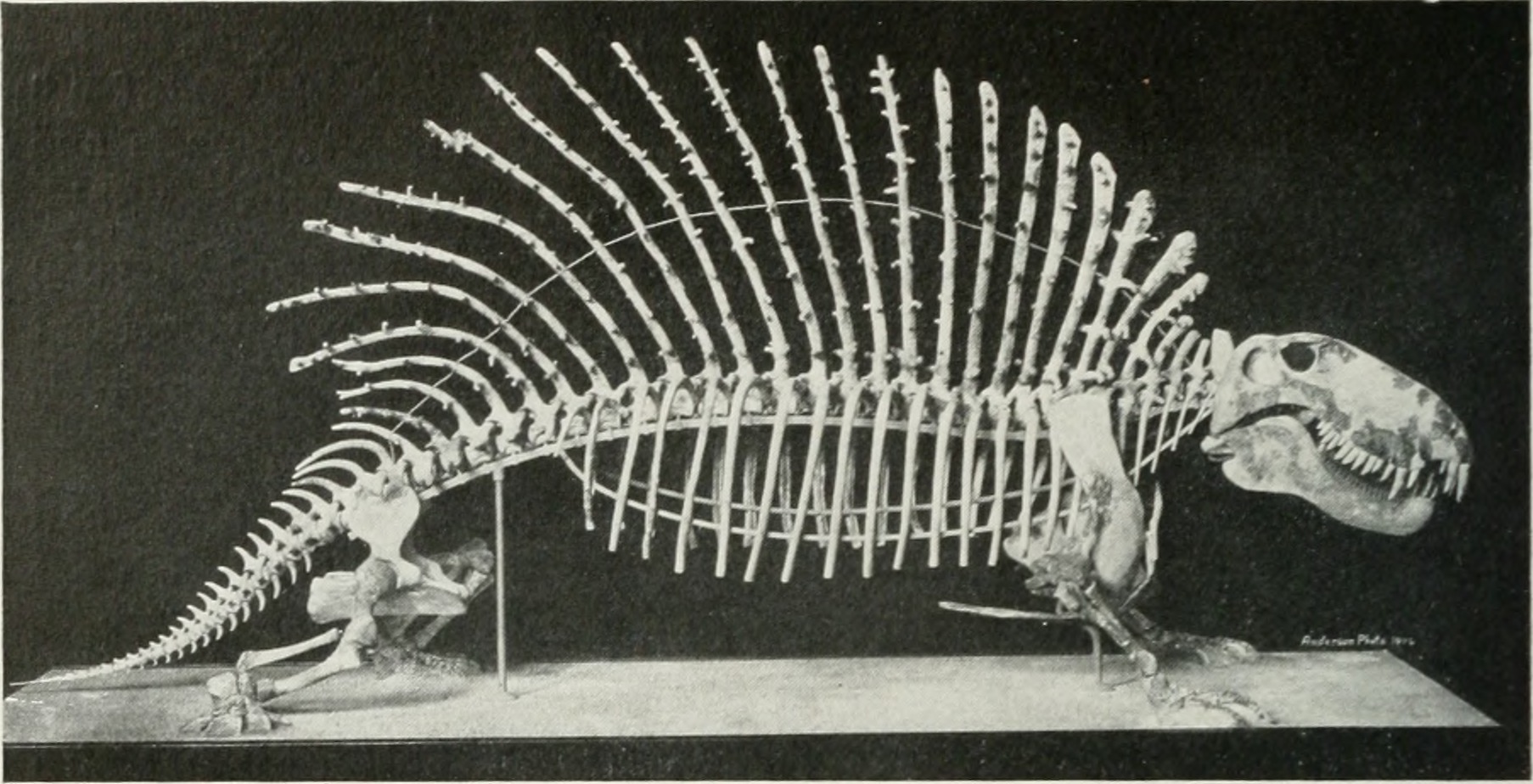

The diversity was staggering. Alongside the famous giants swam smaller but equally fascinating creatures like Henodus, a turtle-like reptile that looked more like a coffee table than a swimmer, and Tanystropheus, a bizarre long-necked reptile that spent its time both in water and on land.

Evolutionary Innovations

These marine reptiles didn’t just grow large—they evolved some of the most sophisticated adaptations ever seen in aquatic animals. Ichthyosaurs developed echolocation abilities similar to modern dolphins, using sound waves to navigate murky waters and locate prey. Their inner ear structures show remarkable similarities to those of modern toothed whales.

Plesiosaurs evolved a unique swimming style using all four flippers in a coordinated underwater “flight” pattern, similar to modern sea turtles but far more efficient. This four-flipper propulsion system has never been successfully replicated by any other group of animals, making plesiosaurs truly one-of-a-kind.

Perhaps most remarkably, several groups independently evolved live birth, abandoning the reptilian tradition of laying eggs. This adaptation allowed them to remain fully aquatic throughout their entire life cycle, never needing to return to land like modern sea turtles.

The Great Dying

The end of the Mesozoic Era brought catastrophe to these ocean giants. The same asteroid impact that killed the dinosaurs also spelled doom for most marine reptiles. The sudden climate change, acid rain, and collapse of marine food chains created a perfect storm of extinction that these magnificent creatures couldn’t survive.

Mosasaurs, having evolved later, were particularly vulnerable to these changes. Their specialized diet and large size made them dependent on stable ecosystems that simply vanished overnight in geological terms. The last mosasaurs disappeared within a few thousand years of the impact, ending their brief but spectacular reign.

Only a few groups managed to survive this apocalypse. Sea turtles, crocodiles, and some smaller marine reptiles scraped through, but the age of marine reptile giants was forever over. The oceans would never again see such diversity and size among their reptilian inhabitants.

Modern Ocean Comparisons

Today’s oceans, impressive as they are, pale in comparison to the marine reptile diversity of the Mesozoic. Modern marine mammals like whales and dolphins fill similar ecological niches, but they’re relative newcomers compared to the 150-million-year reign of marine reptiles. The largest animal ever to live, the blue whale, is certainly impressive, but it’s a filter-feeder, not a predator.

The closest modern equivalent to a pliosaur might be the orca, but even these apex predators are dwarfed by their ancient counterparts. A full-grown Liopleurodon would have considered a modern orca a snack rather than a rival. The bite force comparison isn’t even close—modern marine predators simply don’t possess the crushing power of ancient pliosaurs.

What’s perhaps most striking is the complete absence of large marine reptiles in modern oceans. Today’s marine reptiles—sea turtles, marine iguanas, and sea snakes—are relatively small and specialized, nothing like the giants that once ruled the waves.

Fossil Discovery Hotspots

The best marine reptile fossils come from specific locations around the world where ancient seas once covered the land. The Jurassic Coast of England has produced some of the most complete ichthyosaur and plesiosaur specimens, including the famous fossils discovered by Mary Anning in the early 1800s. These coastal cliffs continue to erode, revealing new specimens regularly.

Germany’s Holzmaden formation is another treasure trove, preserving not just bones but soft tissues, stomach contents, and even unborn young. These exceptional fossils have revolutionized our understanding of how these creatures lived, reproduced, and died. The preservation is so good that scientists can see the outline of skin and identify their last meals.

More recently, discoveries in Kansas, Australia, and Argentina have expanded our knowledge of marine reptile diversity. Each new find adds pieces to the puzzle of ancient ocean ecosystems, revealing new species and filling gaps in our understanding of marine reptile evolution.

Breathing Adaptations

One of the most challenging aspects of marine reptile evolution was solving the breathing problem. Unlike fish, these creatures needed to breathe air, but they lived their entire lives in water. Different groups evolved different solutions to this challenge, and their success determined how long they could stay submerged and how deep they could dive.

Ichthyosaurs developed enlarged lungs and modified blood chemistry that allowed them to hold their breath for extended periods. Fossil evidence suggests they could dive to depths of over 1,600 feet, deeper than most modern marine mammals. Their large eyes weren’t just for hunting—they were essential for navigating in the near-total darkness of the deep ocean.

Plesiosaurs took a different approach, maintaining contact with the surface through their incredibly long necks. This allowed them to breathe while keeping their bodies submerged, reducing energy expenditure and maintaining their position in the water column. It was an elegant solution that no modern animal has replicated.

Baby Giants

Perhaps the most touching aspect of marine reptile research involves the discovery of juvenile specimens and evidence of parental care. Unlike most modern reptiles, many marine reptiles gave birth to live young and may have provided some level of parental protection. Ichthyosaur fossils have been found with unborn young still inside the mother, showing that these creatures gave birth tail-first like modern whales.

Young marine reptiles faced incredible challenges in the ancient oceans. They had to avoid not only the various predators but also cannibalistic adults of their own species. Fossil evidence suggests that juvenile mortality was extremely high, with only a small percentage surviving to adulthood. This high mortality rate may have driven the evolution of increasingly large size as a defense mechanism.

Some species appear to have had nursery areas where young could grow in relative safety. These shallow, protected waters would have provided abundant food and shelter from larger predators, similar to how modern sharks use nursery areas for their young.

Climate and Ocean Chemistry

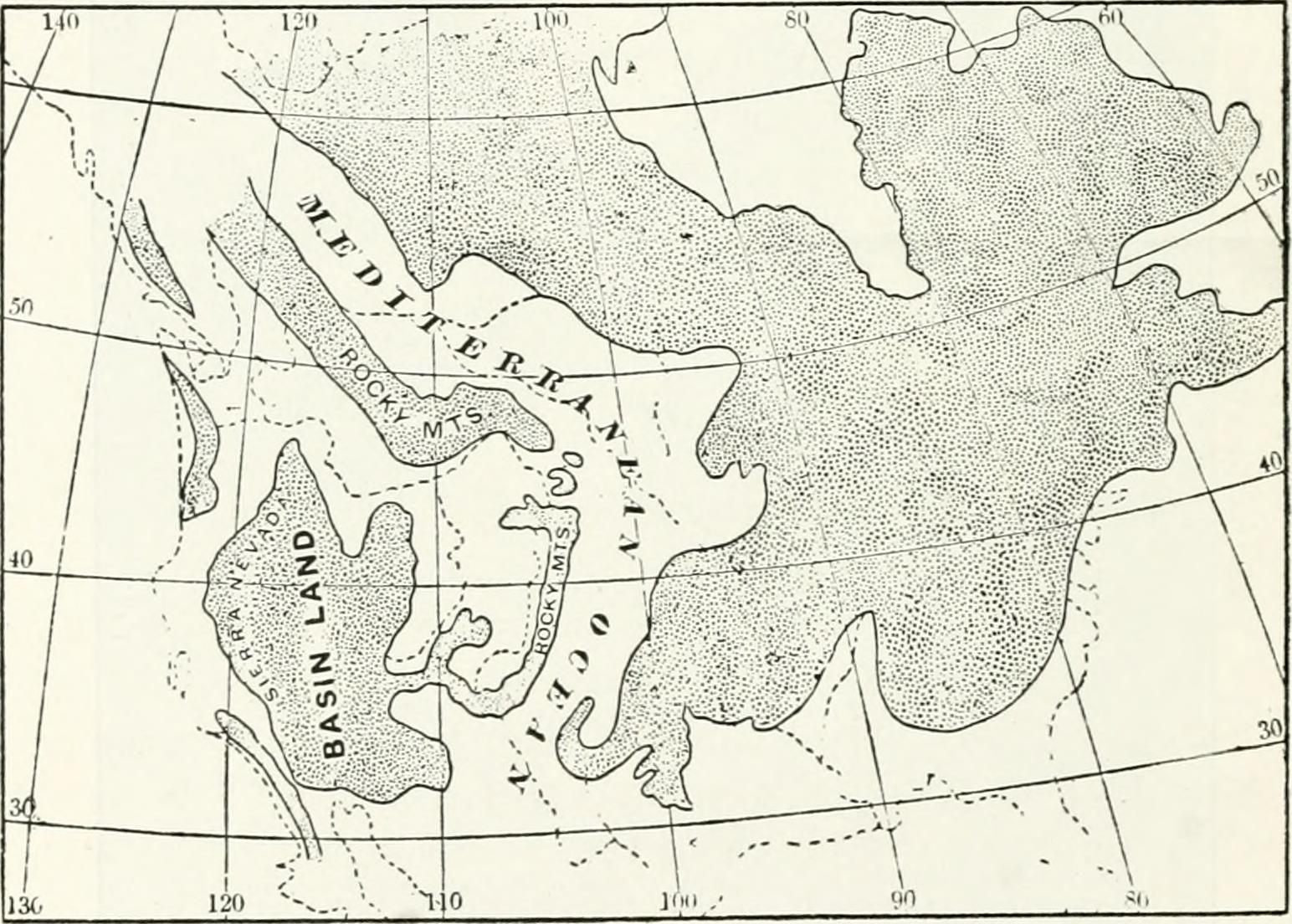

The success of marine reptiles was closely tied to the climate and ocean chemistry of their time. The Mesozoic Era was characterized by greenhouse conditions, with no polar ice caps and much warmer global temperatures. This created vast warm seas that supported the massive food chains necessary to sustain giant marine predators.

Ocean oxygen levels were also different during the Mesozoic, with periods of both higher and lower oxygen content than today. These fluctuations affected the entire marine ecosystem, sometimes favoring larger animals and sometimes smaller ones. The relationship between ocean chemistry and marine reptile diversity is still being studied, but it’s clear that environmental changes played a crucial role in their evolution.

The position of continents was also dramatically different, with much of what is now dry land covered by shallow seas. These inland seas, like the Western Interior Seaway that split North America, created new habitats and evolutionary opportunities for marine reptiles.

The Legacy Lives On

While the age of marine reptile giants is long over, their influence on our planet’s history cannot be overstated. These creatures dominated Earth’s oceans for longer than mammals have existed on land, shaping marine ecosystems and evolutionary pathways in ways we’re still discovering. Their fossilized remains continue to reveal new secrets about life in ancient seas.

Modern marine conservation efforts can learn from studying these ancient ecosystems. The diversity and success of marine reptiles show what’s possible when oceans are healthy and food webs are intact. Their extinction reminds us how quickly things can change when environmental conditions shift rapidly.

Every new fossil discovery adds to our understanding of these magnificent creatures, and new species are still being discovered regularly. Advanced imaging techniques and chemical analysis of fossils continue to reveal new details about their lives, from their body temperatures to their swimming speeds to their social behaviors.

The next time you’re swimming in the ocean, take a moment to imagine what those waters might have looked like 150 million years ago. The gentle waves lapping at your feet once witnessed battles between titans that would make today’s most dramatic nature documentaries look tame by comparison. What other secrets might still be waiting in the depths, preserved in stone for future generations to discover?