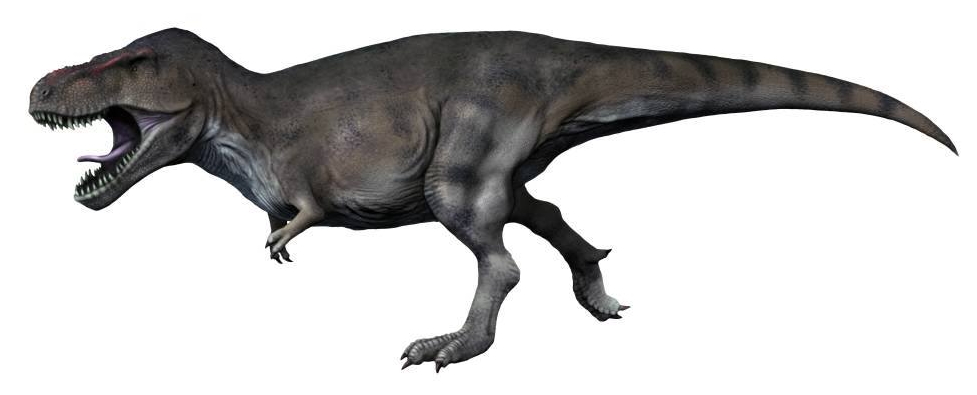

Your fascination with that massive T. rex skull at the museum might need a reality check. Remember when scientists claimed these prehistoric giants had the brainpower of modern primates? Well, the newest research suggests you should think more crocodile, less chimpanzee when imagining how smart Tyrannosaurus rex really was.

For over six decades, we’ve been picturing dinosaurs as dim-witted giants stomping through prehistoric landscapes with barely enough brains to find their next meal. Recent studies have completely overturned this view, though the pendulum has swung back toward a more moderate understanding of dinosaur intelligence.

The controversial claim that started it all

In 2023, prominent neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel of Vanderbilt University made waves when she claimed that dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex were far more intelligent than previously believed. She argued that T. rex had an exceptionally high number of neurons, suggesting it may have been as smart as a baboon and capable of cultural transmission of knowledge and tool use.

The discovery put T. rex’s forebrain on par with modern baboons’ when Herculano-Houzel calculated that the predator had 3.3 billion neurons in one part of the forebrain alone. Think about that for a moment. If true, this would mean you were dealing with creatures that could potentially use tools, learn from experience, and pass knowledge to their offspring.

The provocative study was immediately greeted with skepticism in the scientific community. An international team of paleontologists, neuroanatomists and cognitive psychologists has conducted a new study that refutes Herculano-Houzel’s claims.

Why the baboon comparison doesn’t hold water

Reptile brains don’t fill up the skull cavity like mammal and bird brains do. There is a lot of cerebrospinal fluid taking up space as well. Picture dissecting an alligator’s skull and being surprised by how much empty space surrounds the actual brain tissue.

In modern alligators and crocodiles, the brain only occupies about 30% of the cranial cavity. In birds and mammals, it’s close to 100%. This fundamental difference means early estimates dramatically overestimated T. rex brain size.

The new findings suggest that the earlier study overestimated the number of neurons in T. rex brains. While adult baboons weigh between 30 and 88 pounds, a fully grown T. rex could weigh as much as 15,000 pounds, meaning it would have needed a proportionately larger number of neurons to maintain basic biological functions.

Body size matters more than you think

An adult male baboon can range from 14 to 40 kilograms, while a T. rex could be in the neighborhood of 7 tons. The number of neurons scales with the body size. This scaling relationship becomes crucial when comparing intelligence across vastly different animal sizes.

A larger animal needs more neurons just for basic functions. That means T. rex needed a lot of neurons for just doing the basics with such a large body, with none left over for using tools and transmitting cultural knowledge.

Even if a T. rex brain held as many neurons as a baboon’s or a magpie’s, that brain had a lot more body to operate. A T. rex weighed seven tonnes while a baboon weighs 40 kilos. Imagine trying to run a massive factory with the same control system designed for a small workshop.

The revised neuron count tells a different story

The T. rex telencephalon had closer to 360 million neurons according to new estimates. When recalculating with a smaller brain volume, the amount of neurons in the telencephalon dropped from 3.3 billion to 1.2 billion, and using reptile neuron density reduced it even further to between 245 million and 360 million.

The new estimate suggests that T. rex’s forebrain is more similar to that of modern crocodiles than of primates. This dramatic reduction in estimated intelligence changes everything about how we should picture these ancient predators.

Reptiles have fewer neurons per square centimeter of brain than birds. When calculating the number of neurons in extinct theropods, researchers must decide whether to use the neuron densities of birds, reptiles or some combination of the two.

What crocodile intelligence actually looks like

Recent studies have found that crocodiles and their relatives are highly intelligent animals capable of sophisticated behavior such as advanced parental care, complex communication and use of tools for hunting. Modern crocodilians aren’t the mindless killing machines popular culture portrays them as.

Crocodiles use tools for hunting, displaying sticks across their snouts to lure nest-building birds. The crocodiles remained still for hours and if a bird neared the stick, they would lunge. This represents genuine problem-solving behavior tied to seasonal prey patterns.

Crocodiles conduct highly organized game drives, swimming in circles around shoals of fish, gradually making the circle tighter until the fish were forced into a tight ball, then taking turns cutting across the center to snatch fish.

Tool use isn’t as advanced as you might think

This represents the first report of tool use by any reptiles, and also the first known case of predators timing the use of lures to a seasonal behavior of the prey. However, the sophistication of this tool use differs significantly from what we see in primates or birds.

Alligators were observed floating motionless in the water with small piles of sticks stacked on their heads and snouts during migratory bird nesting season. Though very primitive, the use of any object to obtain food in such a manner does count as using tools.

Some crocodilians use small sticks to lure in birds seeking nesting materials. Alligators position branches and twigs on top of their snout that birds might use for nesting material, then when a bird tries to grab one, the alligator can grab a snack. They only do this during nesting season.

The social complexity question

Reptiles don’t have the same kinds of connections and circuits in their brains that mammals and birds have, which would limit the complexity of their social behaviours. This neurological constraint significantly impacts how we should understand T. rex social dynamics.

Alligators are capable of communication through growling, yelping, hissing, bellowing, and head slapping. They produce infrasonic vibrations below water and settle disputes by head-slapping, using their own language to sort out hierarchy when sharing territory.

Sometimes animals of different size take up different roles, with larger alligators driving fish from deeper parts into shallows where smaller, more agile alligators block escape routes. In one case, a huge saltwater crocodile scared a pig into running where two smaller crocodiles were waiting in ambush.

Memory and learning capabilities

Crocodilians can recognize patterns, making it possible to train them through positive reinforcement. When rewarded for calm behavior and ignored for aggression, they begin to adjust their behavior accordingly to receive rewards each time.

Some alligators become so attentive during training that they anticipate commands by picking up on involuntary muscle twitches from trainers. Some facilities have even managed to teach alligators to recognize their own names.

Learning particular hunting behaviors, parenting, mating, and communication all require memory. The drive to experiment and try out different ideas to get their next meal is instinctive.

Problem-solving in prehistoric proportions

Alligators are capable of solving problems and figuring things out. In their quest to find territory, alligators have been witnessed climbing trees and chain-link fences rather than taking longer routes to get around. This demonstrates flexible thinking within their reptilian cognitive framework.

Problem solving is a basic survival skill that we often equate with smarter brains. However, without the ability to find solutions to problems like finding food, mates, and nesting sites, alligators would not be one of the most ancient species on the planet today.

Alligators construct dens in areas where they need to pass the winter and position their snouts in freezing areas where they must brumate. These behaviors show planning and environmental adaptation that would have been equally valuable for T. rex.

Why this matters for understanding T. rex behavior

T. rex was probably only about as smart as a crocodile, not a baboon. That was likely a very good thing for the animals being hunted by T. rex, though it doesn’t mean the theropod didn’t have a decent reptile brain.

T. rex had a decent reptile brain and was able to dominate the world for millions of years, which is no mean feat. Crocodilian-level intelligence proved more than sufficient for apex predator success over geological timescales.

The possibility that T. rex might have been as intelligent as a baboon is fascinating and terrifying, but all the data we have is against this idea. They were more like smart giant crocodiles, and that’s just as fascinating.

Conclusion

The debate over T. rex intelligence reveals how much we still don’t know about these magnificent creatures that dominated Earth millions of years ago. While they may not have been tool-using, culture-building geniuses, T. rex and similar animals were not on par with avian or mammalian tool-users, but this doesn’t make them any less interesting, sophisticated or complex than we’ve conventionally imagined them.

Understanding T. rex as having crocodilian-level intelligence actually makes their success even more impressive. These weren’t bumbling giants stumbling through prehistoric forests. They were efficient, adaptable predators with enough cognitive flexibility to thrive for millions of years. Sometimes the most elegant solutions come from minds that focus on what really matters: survival, reproduction, and dominating your ecosystem.

What do you think about this more modest view of dinosaur intelligence? Tell us in the comments.