Picture yourself diving into the inky depths of an ancient ocean over half a billion years ago. There’s no moon above, no sun breaking through the water’s surface. Yet somehow, around you, the darkness flickers to life with ghostly glows and ethereal lights. These aren’t alien ships or underwater volcanoes. They’re living creatures producing their own illumination through pure chemistry.

This isn’t science fiction. Recent discoveries have completely transformed how scientists understand the history of life’s most mesmerizing trick: bioluminescence. The oceans of our planet’s deep past were far stranger and more luminous than anyone imagined.

The Oldest Light Show on Earth Started Earlier Than Anyone Thought

Bioluminescence first evolved in animals at least 540 million years ago in a group of marine invertebrates called octocorals. That’s a staggering revelation because it pushes the timeline back by nearly 300 million years from what scientists previously believed. Before this discovery, researchers thought tiny crustaceans called ostracods held the record, glowing their way through ancient seas around 267 million years ago.

Scientists concluded that they shared a primeval light-bearing ancestor that lived 540 million years ago, a creature that would have emerged during the Cambrian Explosion, a period in Earth’s history of seemingly supercharged evolutionary activity. This was the era when major animal groups appeared for the first time, and apparently, they were already experimenting with producing their own light. The implications are honestly mind-blowing when you think about it.

Octocorals Were the Pioneer Glow Artists of Ancient Seas

Octocorals are an evolutionarily ancient and frequently bioluminescent group of animals that includes soft corals, sea fans and sea pens, and like hard corals, octocorals are tiny colonial polyps that secrete a framework that becomes their refuge. Think of them as the soft, branching cousins of the hard corals you might see on a reef vacation today. Except these delicate creatures hold secrets to one of nature’s oldest light displays.

Octocorals that glow typically only do so when bumped or otherwise disturbed, leaving the precise function of their ability to produce light a bit mysterious. That’s what makes them so fascinating yet puzzling. They don’t constantly shine like underwater lightbulbs. Instead, they flash when touched, creating momentary bursts of cold light in the darkness. Scientists are still scratching their heads about why exactly they developed this ability.

How Researchers Traced Light Back Through Time

Scientists created a map of evolutionary relationships using genetic data from 185 species of octocorals, then situated two octocoral fossils of known ages within the tree according to their physical features and were able to use the fossils’ ages and their respective positions to figure out roughly when octocoral lineages split apart. It’s like detective work using both ancient bones and modern DNA to reconstruct a family tree stretching back hundreds of millions of years.

The team employed sophisticated statistical techniques, and every method they tried reached the same stunning conclusion. Some 540 million years ago, the common ancestor of all octocorals were very likely bioluminescent. Multiple independent analyses all pointing to the same ancient moment makes the finding incredibly robust. It’s hard to say for sure, but this looks like one of those discoveries that rewrites textbooks.

The Chemical Magic Behind Ancient Underwater Glow

Just as in all bioluminescent organisms, the enzyme luciferase interacts with the compound luciferin to create light among the octocorals. This is nature’s original light bulb, running on biochemistry instead of electricity. The reaction produces what scientists call cold light because it generates almost no heat, unlike the incandescent bulbs humans eventually invented.

Ancient octocorals likely gained bioluminescence ability because of a biological quirk, as bioluminescent light was likely a byproduct of a more ancient antioxidant-like pathway. Let’s be real, that’s a remarkable twist. The glow might have started as a side effect of dealing with damaging molecules in cells, and only later got repurposed into communication or defense. Evolution is nothing if not resourceful, taking accidents and turning them into advantages.

A Cambrian Ocean Lit by Living Lanterns

Interactions involving light occurred between species during a time when animals were rapidly diversifying and occupying new niches, pointing to bioluminescence as one of the earliest types of communication in the oceans. Imagine the Cambrian seas: predators were evolving new hunting strategies, prey were developing defenses, and eyes were just beginning to appear. In this evolutionary arms race, being able to produce light offered incredible possibilities.

Since creatures with eyes and other light-sensitive photoreceptors had already appeared in the Cambrian era, it is plausible to think that communication using light between anthozoans and other photoreceptor-bearing organisms was in place at that time. The timing is almost too perfect to be coincidence. Eyes evolved to detect light, and bioluminescent creatures evolved to produce it, all during the same explosive period of innovation. The ancient oceans must have been a spectacular light show.

Bioluminescence Became Evolution’s Favorite Trick

Bioluminescence has evolved independently at least 94 times, first emerging in octocorals some 540 million years ago. That’s not a typo. Nearly a hundred separate times, completely unrelated organisms stumbled upon the same solution to survival challenges. From fireflies on land to anglerfish in the deepest trenches, countless lineages independently discovered how to make their own light.

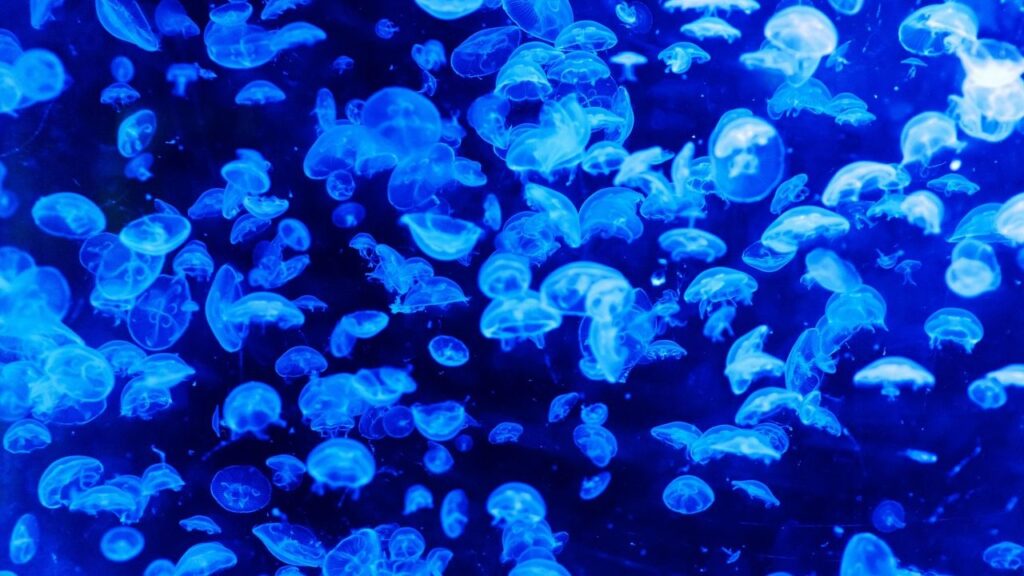

Three-quarters of marine animals are able to light themselves up in some way, and there’s almost no limit to their creativity, as it’s so diverse and variable. In today’s oceans, bioluminescence is everywhere you look once you descend below where sunlight reaches. Some creatures use it to find mates, others to blind predators, still others as lures to attract prey. The sheer variety of applications shows just how valuable this ability became over evolutionary time.

The Deep Past Still Glows With Mysteries

There is still much more to learn before scientists can understand why the ability to produce light first evolved, and though their results place its origins deep in evolutionary time, the possibility remains that future studies will discover that bioluminescence is even more ancient. Here’s the thing: we might be looking at just the tip of the iceberg. Fossilization rarely preserves soft tissues or chemical signatures of bioluminescence, so the actual origin could stretch even further back into the murky past.

The octocorals’ thousands of living representatives and relatively high incidence of bioluminescence suggests the trait has played a role in the group’s evolutionary success, and the fact that it has been retained for so long highlights how important this form of communication has become for their fitness and survival. When a feature sticks around for over half a billion years across thousands of species, you know it’s doing something right. The ancient oceans weren’t just dark and lifeless depths. They sparkled with living lights, creating an alien beauty that predates dinosaurs, forests, or even fish as we know them today.

What do you think about the idea that communication through light might be one of the oldest languages on Earth? Share your thoughts in the comments below.