The Mesozoic Era, spanning from 252 to 66 million years ago, was a time when Earth’s landscapes and oceans teemed with formidable predators that have captivated our imagination since their fossilized remains were first discovered. Often called the “Age of Reptiles,” this vast period witnessed the rise and fall of some of the most fearsome hunters ever to walk the planet or swim its seas. Across three distinct periods—the Triassic, Jurassic, and Cretaceous—different apex predators dominated various ecosystems around the globe. From the earliest dinosaur predators to massive marine reptiles and flying terrors of the skies, the Mesozoic food webs featured diverse top predators adapted to specific environments and prey. Let’s explore these magnificent beasts that ruled their respective domains, examining how they evolved, what made them successful hunters, and how they established ecological dominance across different regions of the prehistoric world.

The Dawn Predators: Triassic Rulers

The Triassic period (252-201 million years ago) represents the beginning of the Mesozoic Era and emerged in the aftermath of the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event. During this recovery phase, several groups competed for the top predator niches. Archosaurs—the group that would eventually give rise to dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and crocodilians—began their ascent to dominance. One of the earliest apex predators was Postosuchus, a quadrupedal archosaur reaching up to 4-5 meters in length that patrolled what is now North America. In South America, Herrerasaurus emerged as one of the earliest dinosaurian predators, standing on two legs with sharp, serrated teeth and grasping hands. Meanwhile, in the seas, early ichthyosaurs and marine reptiles like Nothosaurus were establishing themselves as formidable hunters, showcasing the diverse evolutionary pathways that predators were taking across different environments.

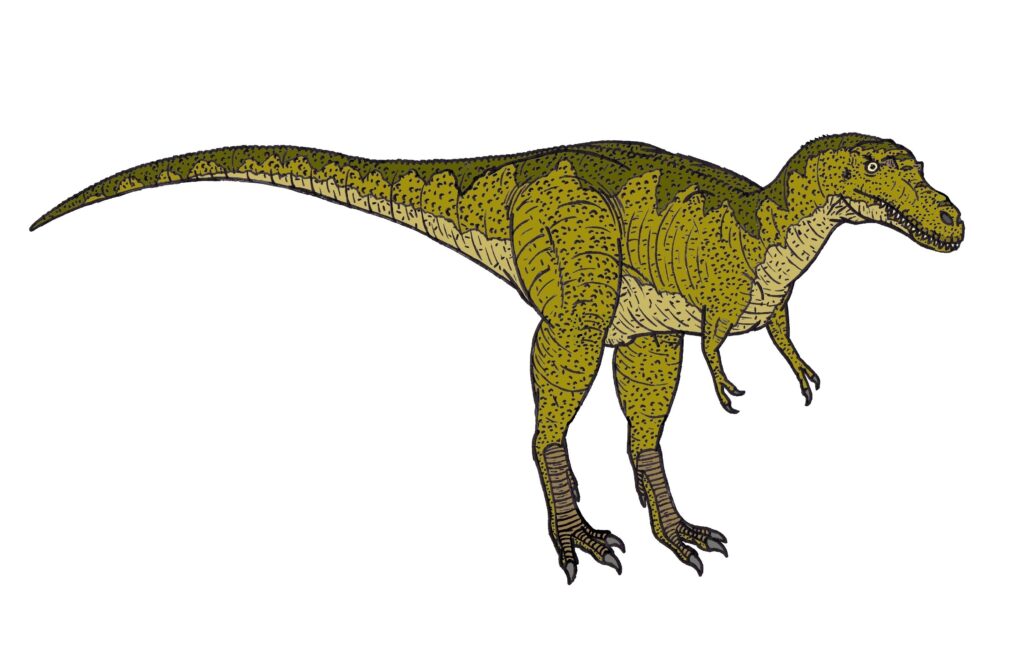

Allosaurs: The Jurassic’s Premier Killers

The Jurassic period (201-145 million years ago) saw the rise of allosaurs as dominant terrestrial predators across much of the globe. Allosaurus itself, reaching lengths of 8-12 meters and weighing up to 2 tons, ruled the late Jurassic landscapes of North America with its powerful build and blade-like teeth designed for slicing through flesh. These hunters possessed relatively long arms with three-fingered hands bearing sharp claws, giving them greater grasping ability than their later Cretaceous counterparts. The skull of Allosaurus featured kinetic joints that allowed it to open its jaws extremely wide, enabling it to take massive bites from prey, likely including the large sauropods and stegosaurs that shared its habitat. In Europe, similar roles were filled by predators like Megalosaurus, while southern continents hosted other allosauroid relatives adapted to their local prey species and environmental conditions.

Spinosaurus: Africa’s Semiaquatic Giant

North Africa during the mid-Cretaceous period (approximately 112-93 million years ago) was home to perhaps the most unusual of all large theropods: Spinosaurus aegyptiacus. This massive predator, potentially reaching lengths of 14-18 meters, has undergone significant reinterpretation in recent years based on new fossil discoveries. Unlike most large theropods, Spinosaurus possessed a suite of adaptations for a semiaquatic lifestyle, including dense bones, paddle-like feet, and a tall sail-like structure on its back that may have functioned in thermoregulation, display, or even as a rudder-like stabilizing feature while swimming. Its elongated crocodile-like snout and conical teeth were perfectly adapted for catching slippery fish, suggesting it hunted primarily in rivers and coastal environments of prehistoric Africa. This unique ecological niche allowed Spinosaurus to avoid direct competition with more conventional terrestrial predators that shared its ecosystem, including the fearsome Carcharodontosaurus.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: North America’s Ultimate Predator

Few prehistoric creatures have captured public imagination like Tyrannosaurus rex, the apex predator of late Cretaceous North America (68-66 million years ago). Standing up to 12 feet tall at the hip and measuring around 40 feet from nose to tail, T. rex combined enormous size with specialized adaptations for powerful predation. Its massive skull, up to 5 feet long, housed banana-sized serrated teeth capable of crushing bone, and bite force estimates suggest it could exert over 6 tons of pressure—the strongest bite of any known land animal. Though its arms were famously short, they were surprisingly muscular and likely used for close-quarters grappling with prey. Recent research suggests T. rex was not merely an opportunistic scavenger but an active predator with excellent vision, a keen sense of smell, and potentially higher intelligence than earlier assumed. Its prey included large horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and duck-billed hadrosaurs, which it likely ambushed using a combination of stealth and explosive bursts of speed.

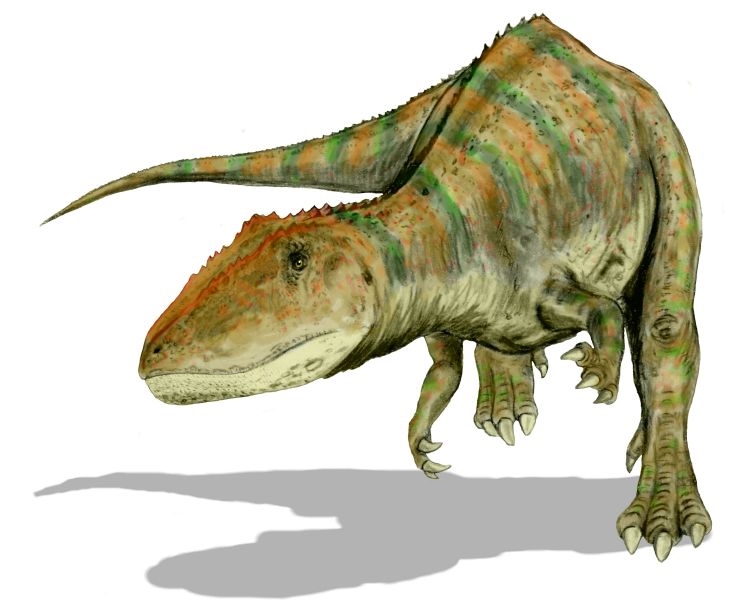

Giganotosaurus and Carcharodontosaurus: Southern Giants

While T. rex dominated North America, equally impressive predators ruled the southern continents during the mid-Cretaceous period. Giganotosaurus carolinii stalked Argentina approximately 98 million years ago, potentially reaching lengths exceeding 13 meters and weighing around 8 tons—dimensions that may have slightly surpassed those of T. rex. Meanwhile, across the gradually widening Atlantic, Carcharodontosaurus saharicus (“shark-toothed lizard”) occupied a similar niche in North Africa. Both belonged to the carcharodontosaurid family, characterized by large, blade-like teeth with fine serrations ideal for slicing through flesh. Unlike the bone-crushing specialization of T. rex, these southern giants evolved to take down the massive sauropod dinosaurs that were abundant in their ecosystems. Their skulls were lighter than those of T. rex, with adaptations for delivering quick, slashing bites rather than crushing bones. These predators represent remarkable examples of convergent evolution, as they developed similar hunting strategies on separate continents.

Mosasaurs: Tyrants of the Late Cretaceous Seas

While dinosaurs dominated land environments, the late Cretaceous oceans belonged to mosasaurs—massive marine reptiles distantly related to modern monitor lizards and snakes. Evolving from semi-aquatic lizards, mosasaurs rapidly diversified to become the undisputed apex predators of Cretaceous seas worldwide between 100-66 million years ago. The largest genus, Mosasaurus, reached lengths of up to 17 meters, powered through the water with a muscular tail featuring a downward kink that supported a shark-like fin, and possessed double-hinged jaws that allowed it to swallow large prey whole. Their paddle-like limbs, streamlined bodies, and conical teeth made them formidable hunters capable of taking down virtually any marine creature they encountered. Mosasaurs fed on fish, ammonites, sea turtles, birds, and even other marine reptiles, occupying various ecological niches with different species specialized for different hunting styles. Their global distribution meant that virtually no ancient coastline was free from these dominant marine predators.

Dakotaraptor: Feathered Terror of the Northern Plains

The discovery of Dakotaraptor in the Hell Creek Formation of South Dakota revolutionized our understanding of dromaeosaurids (“raptors”) by revealing that large, feathered predators existed alongside Tyrannosaurus rex during the latest Cretaceous period. At approximately 5.5 meters long, Dakotaraptor was among the largest dromaeosaurids ever discovered, combining the agility and intelligence associated with smaller raptors with a size that made it capable of tackling substantial prey. Evidence of quill knobs on its forearms indicates it possessed large feathers, despite being far too heavy to fly. Its most formidable weapon was the enlarged, sickle-shaped claw on each second toe, which could be held retracted while running and deployed for devastating slashing attacks during predation. Dakotaraptor likely hunted in a fundamentally different way than T. rex, potentially relying more on speed and precision rather than raw power, allowing these two very different predators to coexist by occupying separate ecological niches within the same ecosystem.

Prehistoric Crocodylomorphs: Ancient Killers

Though often overshadowed by dinosaurs in popular culture, crocodylomorphs—the group including modern crocodilians and their extinct relatives—provided some of the Mesozoic’s most successful predators across diverse habitats. During the Triassic and Early Jurassic, terrestrial forms like Postosuchus and Prestosuchus competed directly with early dinosaurian predators. The Jurassic and Cretaceous periods saw the evolution of marine crocodylomorphs such as Dakosaurus and Metriorhynchus, which developed flipper-like limbs and tail fins for aquatic pursuit predation. Perhaps most impressive were the giant crocodylians of the Late Cretaceous, like Deinosuchus and Sarcosuchus, which could reach lengths exceeding 10 meters and were capable of attacking and killing dinosaurs that came to the water’s edge. These massive ambush predators possessed crushing bite forces that rivaled or exceeded those of the largest theropod dinosaurs. Unlike many dinosaur lineages, crocodylomorphs survived the end-Cretaceous extinction event, with their modern descendants still employing hunting strategies refined over 200 million years of evolution.

Pterosaurs as Aerial Predators

The skies of the Mesozoic were dominated by pterosaurs, flying reptiles that evolved diverse hunting strategies across their 150-million-year reign. Early Jurassic pterosaurs like Dimorphodon were relatively small, with dentition suggesting they captured insects and small vertebrates. By the Late Jurassic, larger pterosaurs such as Rhamphorhynchus hunted fish by skimming low over water bodies, using their elongated jaws lined with needle-like teeth to snatch prey from the surface. The Cretaceous period saw the evolution of truly massive pterosaurs, including the azhdarchids like Quetzalcoatlus and Hatzegopteryx, with wingspans approaching 10-12 meters. These giants are believed to have been terrestrial stalkers that used their long necks and powerful beaks to capture relatively large prey, potentially including small dinosaurs. With their hollow bones, sophisticated wing membranes, and highly developed brains, pterosaurs utilized the aerial domain for hunting in ways not seen again until the evolution of birds, making them true apex predators of prehistoric skies.

Regional Variations: Continental Differences

The gradual breakup of the supercontinent Pangaea throughout the Mesozoic created increasingly isolated landmasses, driving the evolution of distinct predator communities adapted to local conditions and prey species. By the Late Cretaceous, North America hosted tyrannosaurids like T. rex and Albertosaurus, while South America was dominated by abelisaurids such as Carnotaurus, characterized by extremely reduced forelimbs and elaborate skull ornamentation. Africa’s predator guild included both carcharodontosaurids and the fish-eating Spinosaurus, while Europe, then a series of islands, featured unique dwarf forms due to the constraints of island biogeography. Asia developed its specialized predators, including the powerful tyrannosauroids and the unusual therizinosaurs with their massive claws. Australia, connected to Antarctica during this period, has yielded fossils of small but formidable hunters like Australovenator. These regional differences reflect how geography shaped evolutionary trajectories, with each continent developing its unique assemblage of apex predators specially adapted to local environmental conditions and available prey species.

Marine Realm: Evolution of Sea Monsters

The Mesozoic oceans witnessed a remarkable succession of apex predators, with different groups dominating marine ecosystems across the era’s span. The Early Triassic seas saw the radiation of ichthyosaurs, fully aquatic reptiles with dolphin-like bodies and large eyes adapted for deep diving. By the Jurassic, gigantic pliosaurs like Pliosaurus and Liopleurodon had evolved as the ocean’s ultimate predators, with massive 2-meter skulls housing conical teeth ideal for seizing large prey. Their four powerful flipper-like limbs provided explosive acceleration for ambush attacks. The Late Jurassic and Early Cretaceous featured long-necked elasmosaurid plesiosaurs alongside the continuing ichthyosaurs, creating complex marine food webs. The Late Cretaceous saw mosasaurs rise to dominance after the extinction of ichthyosaurs and most pliosaurs, diversifying into numerous species occupying different ecological niches. Throughout these transitions, large predatory fish, including sharks and giant teleosts like Xiphactinus, also maintained important roles as mesopredators. This succession showcases how marine predator guilds evolved in response to changing oceanic conditions and competition throughout the Mesozoic.

The End of an Era: Extinction Patterns

The reign of the Mesozoic apex predators came to an abrupt end 66 million years ago with the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) mass extinction event, triggered primarily by a massive asteroid impact at Chicxulub, Mexico. This catastrophic event eliminated approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs, pterosaurs, mosasaurs, and plesiosaurs. The extinction was particularly devastating for large-bodied apex predators, which required substantial food resources and typically had lower population densities and slower reproductive rates than smaller animals. The immediate aftermath of the impact created conditions hostile to large predators, including a dramatic reduction in sunlight (the “impact winter”), acid rain, and the collapse of food webs based on photosynthesis. Some predatory lineages survived in reduced form, including crocodylians and sharks, which possessed traits advantageous for surviving the extinction: semi-aquatic lifestyles, ability to scavenge, and physiological adaptations allowing extended periods without food. This selective pattern of extinction ultimately opened ecological niches that would later be filled by mammalian predators during the Cenozoic Era, fundamentally reshaping Earth’s predator-prey dynamics.

Legacy and Modern Understanding

Our understanding of Mesozoic apex predators has evolved dramatically in recent decades, transforming them from lumbering, cold-blooded reptiles into complex, dynamic animals with sophisticated behaviors and adaptations. Modern paleontological techniques—including CT scanning, biomechanical modeling, histological analysis of bone microstructure, and comparative studies with living relatives—have revealed that many theropod dinosaurs possessed active metabolisms, potential pack-hunting behaviors, and in many cases, elaborate feather coverings. The discovery that birds are living theropod dinosaurs has fundamentally changed our perspective, allowing us to better interpret fossil evidence through the lens of avian biology. Similarly, studies of extant crocodilians and monitor lizards have informed our understanding of extinct marine reptiles. Beyond scientific significance, these prehistoric apex predators continue to capture public imagination, featuring prominently in entertainment media and serving as “gateway organisms” that inspire interest in natural history, evolution, and conservation. They provide valuable case studies in adaptation, specialization, and the consequences of environmental change—lessons increasingly relevant in our modern era of biodiversity crisis.

Adapting to Rule: Mesozoic Predator Evolution

The Mesozoic apex predators represent one of evolution’s most spectacular experiments in the development of dominant carnivores across terrestrial, marine, and aerial environments. From the earliest archosaurs of the Triassic to the specialized hunters of the Late Cretaceous, these animals evolved remarkable adaptations that made them the undisputed rulers of their respective domains. Their regional diversity, specialized hunting strategies, and successive dominance patterns reflect the complex interplay of geography, climate, and competition throughout 186 million years of evolutionary history. Though their reign ended catastrophically, their evolutionary innovations continue through their descendants—birds and crocodilians—and their scientific and cultural impact remains profound. By studying these magnificent predators, we gain valuable insights into ecological relationships, evolutionary processes, and the dynamic nature of life on Earth across deep time.