The field of paleontology has been punctuated by moments of brilliance and occasional blunders that have shaped our understanding of prehistoric life. Among these fascinating stories of scientific discovery and misinterpretation, few are as intriguing as the case of Iguanodon—a dinosaur whose initial reconstruction became one of paleontology’s most famous mistakes. This remarkable tale of a backward-assembled dinosaur not only illustrates the evolving nature of scientific knowledge but also highlights how interpretations change as new evidence emerges. Let’s delve into this captivating tale of scientific misinterpretation and its eventual correction.

The Discovery of Iguanodon

In 1822, Mary Ann Mantell, wife of British physician and geologist Gideon Mantell, discovered unusual fossilized teeth while walking along a country road in Sussex, England. These teeth caught her husband’s attention, who recognized them as belonging to an unknown prehistoric reptile. After extensive research and comparison with modern iguana teeth, Mantell formally named the creature Iguanodon, meaning “iguana tooth,” in 1825. This discovery was revolutionary, as Iguanodon became one of the first dinosaurs to be scientifically described and named, occurring decades before the term “dinosaur” was even coined by Richard Owen in 1842. The discovery of the teeth would eventually lead to one of the most famous misinterpretations in paleontological history, as scientists attempted to reconstruct an animal from fragmentary remains without a modern understanding of dinosaur anatomy.

Limited Evidence and Victorian Interpretations

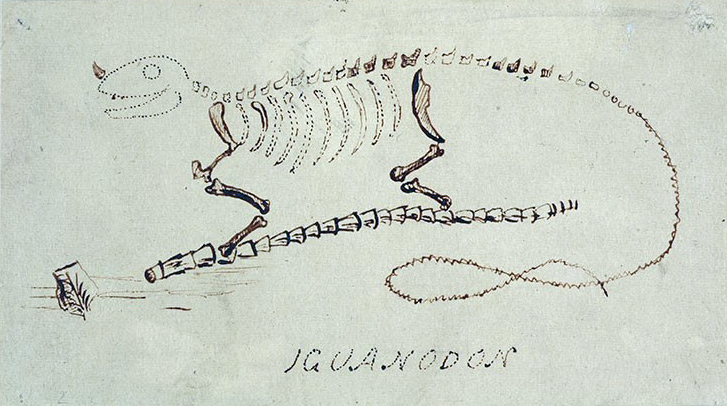

The initial reconstruction of Iguanodon suffered from a severe lack of complete fossil evidence. Paleontologists of the 1820s and 1830s had to work with fragmentary remains – primarily teeth and a few isolated bones. Without a complete skeleton, scientists relied heavily on comparisons with living reptiles, particularly iguanas, as the name suggested. The Victorian era’s understanding of reptiles and evolution was also fundamentally different from our modern perspective. Many scientists of the time couldn’t conceive of dinosaurs as a distinct group of animals with unique characteristics. Instead, they imagined prehistoric creatures as essentially larger versions of modern reptiles, leading them to reconstruct Iguanodon as a massive, iguana-like quadruped. This limited frame of reference led to significant errors when attempting to place bones in their correct anatomical positions.

The Conical Spike Misinterpretation

Perhaps the most dramatic error in Iguanodon’s reconstruction involved a conical spike that was discovered among the fossil remains. Without a complete skeleton for reference, scientists interpreted this bone as a horn that would have been positioned on the creature’s snout, similar to a rhinoceros. Based on this assumption, early illustrations and models depicted Iguanodon with a prominent nasal horn, creating an image that was widely circulated and accepted throughout the scientific community and public imagination. This misplacement was particularly significant because it fundamentally altered the appearance and presumed behavior of the animal. The spike-as-horn reconstruction suggested an animal that might use its nasal weapon for defense or competition, shaping how Victorian society envisioned this prehistoric creature’s behavior and lifestyle.

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The misinterpreted Iguanodon reconstruction achieved its most famous physical manifestation as part of the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, a series of life-sized dinosaur sculptures created by Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins under the scientific direction of Richard Owen. Unveiled in 1854 in London’s Crystal Palace Park, these statues represented the first full-scale dinosaur reconstructions ever created for public display. The Iguanodon statues depicted massive, heavy-set quadrupedal reptiles with the distinctive “horn” on their snouts. These impressive sculptures, though wildly inaccurate by modern standards, were revolutionary for their time and captivated the Victorian public’s imagination. They gave tangible form to prehistoric creatures previously known only through technical scientific papers, effectively bringing dinosaurs into popular culture for the first time.

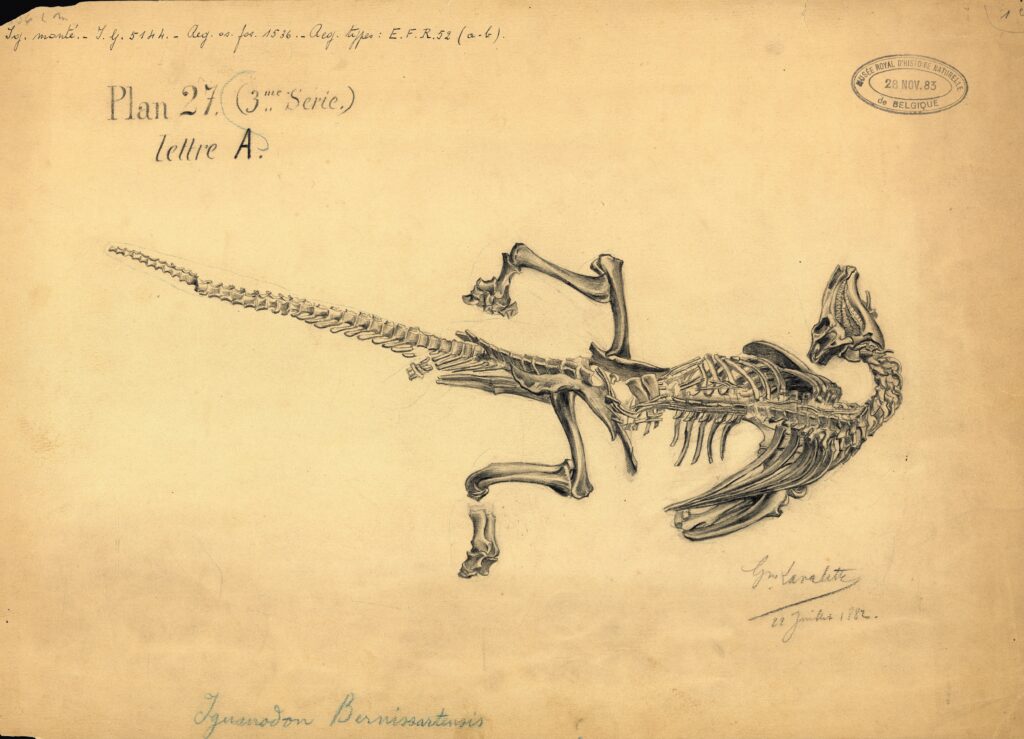

The Bernissart Discovery

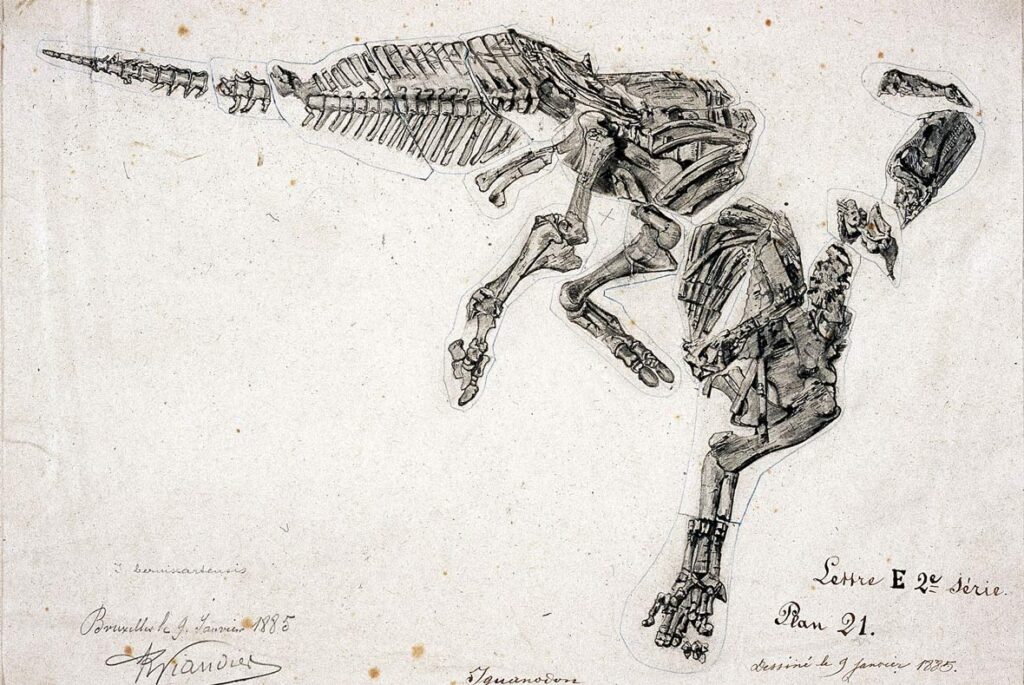

The misinterpretation of Iguanodon persisted until a remarkable discovery occurred in 1878 in a coal mine at Bernissart, Belgium. Miners working deep underground stumbled upon an extraordinary paleontological treasure—not one, but at least 38 complete or nearly complete Iguanodon skeletons preserved in remarkable detail. This unprecedented find provided scientists with complete specimens for the first time, revolutionizing their understanding of Iguanodon’s true anatomy. The Bernissart discovery was carefully excavated under the direction of Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo, who supervised the removal of the massive fossils from nearly 1,000 feet underground. These specimens would finally provide the evidence needed to correct the longstanding misconceptions about Iguanodon’s structure and posture.

Thumbs, Not Horns

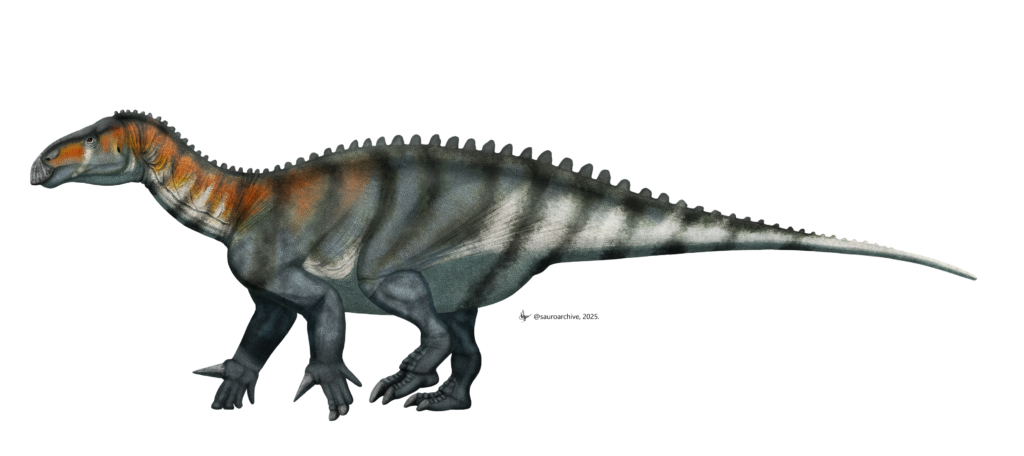

The complete skeletons from Bernissart revealed the true nature of the conical spike that had been misinterpreted as a nasal horn. In reality, this pointed bone was a modified thumb spike that would have protruded from the animal’s hand, not its nose. This dramatic realization fundamentally changed the understanding of Iguanodon’s appearance and functional anatomy. The thumb spike likely served as a defensive weapon against predators or possibly as a tool for breaking down vegetation. This revelation demonstrated how dramatically incorrect the previous reconstructions had been, with a feature that had defined the creature’s appearance for decades being on the wrong end of the animal. The discovery highlighted how scientific interpretations can be completely revised when more complete evidence becomes available.

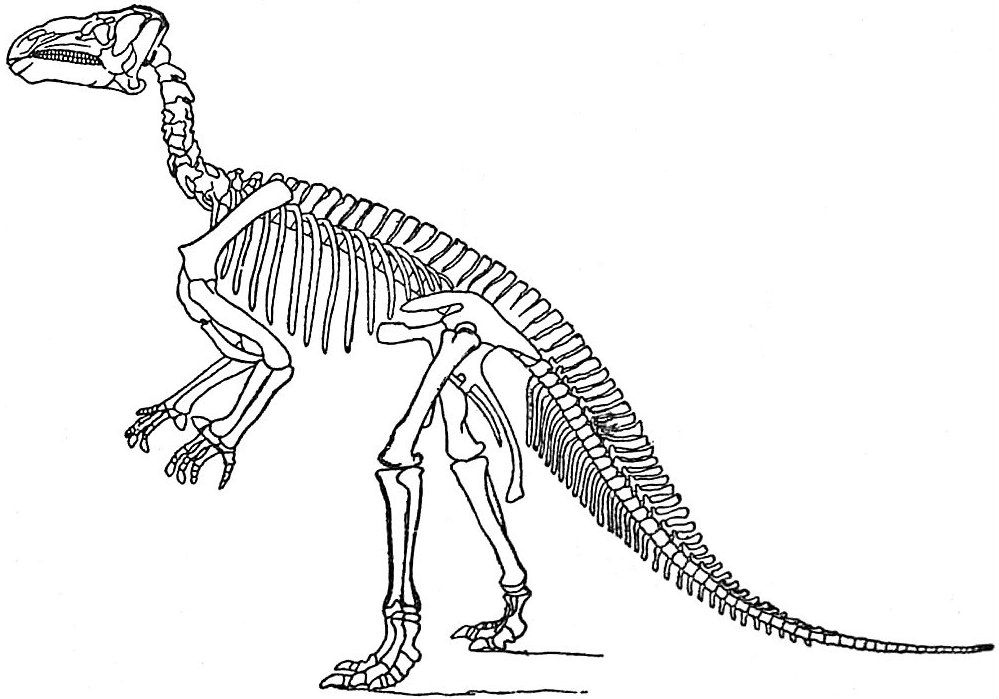

From Quadruped to Biped

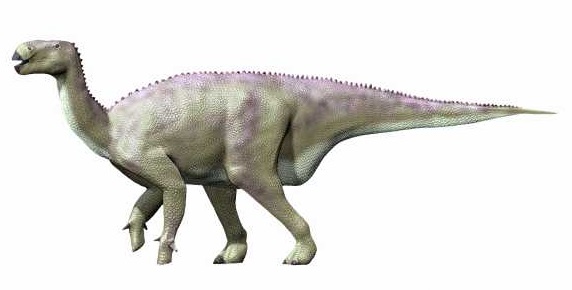

Beyond the thumb spike revelation, the Bernissart specimens demonstrated that Iguanodon was capable of bipedal locomotion, rather than being exclusively quadrupedal as previously depicted. The dinosaur had powerful hind limbs that could support its weight for bipedal walking or running, along with forelimbs that could be used for gathering food or supporting weight when moving slowly. This fundamentally changed the scientific understanding of how Iguanodon moved and behaved. The shift from imagining Iguanodon as a heavy, lumbering quadruped to recognizing it as a creature capable of both bipedal and quadrupedal stances represented a complete reconceptualization of the animal. Modern reconstructions typically show Iguanodon as primarily bipedal but capable of dropping to all fours, with a more horizontal posture than the upright kangaroo-like stance initially proposed after the Bernissart discovery.

Louis Dollo’s Corrected Reconstruction

Belgian paleontologist Louis Dollo led the effort to properly describe and reconstruct Iguanodon based on the Bernissart specimens. Beginning in 1882, Dollo published a series of papers that systematically corrected the previous misinterpretations and established a much more accurate understanding of Iguanodon’s anatomy. Dollo’s work was methodical and groundbreaking, utilizing complete skeletons to determine proper bone placement and articulation. He carefully mounted several of the Bernissart specimens for display at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels, where they remain impressive exhibits today. Dollo’s reconstructions presented Iguanodon in a kangaroo-like posture with an upright body, tail touching the ground for support, and forelimbs raised—a significant improvement over previous models, though later research would further refine this understanding.

The Legacy of the Mistake

The backward assembly of Iguanodon has become one of the most celebrated cases of scientific error and correction in paleontological history. Rather than being viewed as an embarrassment, this mistake is now valued as an important lesson in the scientific process. The case demonstrates how science advances through proposing hypotheses based on available evidence, then revising those hypotheses when new evidence emerges. Museums and educational programs often highlight this story to illustrate how scientific knowledge evolves. The Crystal Palace Iguanodon statues, incorrect as they are, have been preserved as Grade I listed structures in the United Kingdom, recognized for their historical significance in the development of paleontological science and public understanding of prehistoric life.

Modern Understanding of Iguanodon

Today’s understanding of Iguanodon continues to evolve with discoveries and analytical techniques. Modern reconstructions depict Iguanodon as a large herbivorous dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 125-122 million years ago. It stood about 10 feet tall, measured roughly 30 feet long, and weighed around 4-5 tons. Paleontologists now recognize that Iguanodon likely used its distinctive thumb spikes for defense against predators like Neovenator and Baryonyx. The genus Iguanodon has undergone significant taxonomic revision in recent decades, with many specimens formerly attributed to Iguanodon now classified as separate genera, including Mantellisaurus and Ouranosaurus. These refinements reflect the ongoing process of scientific revision as new specimens are discovered and analytical methods improve.

Other Famous Fossil Reconstruction Errors

Iguanodon’s backward assembly is just one example in a long history of paleontological reconstruction errors. Another famous case involved Apatosaurus (formerly known as Brontosaurus), which was initially displayed with the wrong skull—a Camarasaurus skull—for many years at the American Museum of Natural History. Diplodocus was once depicted with its nostrils on top of its head like a blowhole, a misconception later corrected through more careful anatomical studies. Early reconstructions of Tyrannosaurus rex showed it in an upright “kangaroo stance” with its tail dragging on the ground, while modern evidence indicates a more horizontal posture with the tail held straight out for balance. These examples demonstrate that reconstruction errors are a natural part of the scientific process when working with incomplete fossil evidence, and corrections occur as more specimens are discovered and studied.

The Value of Scientific Mistakes

Scientific mistakes like the backward assembly of Iguanodon serve an important role in the advancement of knowledge. These errors, when recognized and corrected, demonstrate the self-correcting nature of the scientific method and provide valuable learning opportunities for both scientists and the public. The progression from error to correction illustrates how science builds upon previous work, with each generation of researchers refining the understanding developed by their predecessors. Such mistakes also highlight the challenges inherent in paleontological work, where scientists must often make substantial inferences based on fragmentary evidence. Additionally, these historical errors provide important context for public understanding of science as an evolving process rather than a static collection of facts, showing that science is a human endeavor subject to improvement and refinement over time.

Paleontology in the Modern Era

Modern paleontologists benefit from technological advantages that help prevent reconstruction errors like those that affected early Iguanodon models. Advanced imaging techniques such as CT scanning allow scientists to examine fossils without damaging them and to visualize internal structures invisible to the naked eye. Computer modeling and 3D printing enable researchers to test hypotheses about how fossil bones fit together and how extinct animals moved. Comparative anatomy has become more sophisticated, with larger fossil databases and a better understanding of evolutionary relationships helping scientists make more accurate comparisons between ancient and modern animals. Despite these advances, paleontologists still face fundamental challenges when reconstructing extinct creatures, particularly regarding soft tissues, coloration, and behaviors that rarely preserve in the fossil record. The field continues to evolve, with discoveries frequently challenging established interpretations.

Conclusion

The story of Iguanodon’s backward assembly stands as a fascinating chapter in the history of paleontology. This famous mistake—transforming a thumb spike into a nose horn—reminds us that scientific knowledge is not static but evolves as new evidence emerges. The progression from the Crystal Palace sculptures to modern reconstructions illustrates the self-correcting nature of science and the importance of complete evidence in drawing accurate conclusions. Rather than being hidden away as an embarrassment, this error is celebrated as a valuable lesson in scientific methodology. As we continue to unearth new fossils and develop advanced analytical techniques, our understanding of prehistoric life will undoubtedly continue to transform, perhaps correcting misconceptions we don’t yet recognize. The backward dinosaur stands as a humble reminder that in science, being wrong in interesting ways often leads to being more right in the future.