The prehistoric world was a realm of constant change, where massive landmasses shifted, climates fluctuated dramatically, and life adapted in remarkable ways. Among the most fascinating questions paleontologists explore is whether dinosaurs migrated between the Americas during their 165-million-year reign on Earth. Recent fossil discoveries and advanced geological research have begun to paint a clearer picture of dinosaur distribution across the Western Hemisphere, suggesting complex patterns of movement that challenge our understanding of these magnificent creatures. As we piece together the puzzle of dinosaur evolution and distribution, the question of migration between North and South America emerges as a critical element in understanding the broader story of life on our planet.

The Continental Puzzle: Pangaea and Its Breakup

When dinosaurs first evolved around 230 million years ago, Earth’s landmasses were united in the supercontinent Pangaea. This geological arrangement meant dinosaurs could theoretically range across what would eventually become separate continents. By the Late Jurassic period (about 150 million years ago), Pangaea had begun fracturing, with North and South America gradually separating as the Atlantic Ocean formed between them. This continental drift created increasingly isolated ecosystems where dinosaur populations evolved along separate trajectories. Understanding this changing geography is essential for interpreting any evidence of migration, as the physical connections between landmasses determined whether dinosaurs could travel between them or were forced to evolve in isolation.

Land Bridges: Prehistoric Highways

Despite the gradual separation of the Americas, geological evidence suggests periodic land connections existed at various points in the Mesozoic Era. These land bridges would have served as crucial migration corridors for dinosaurs and other terrestrial animals. The Central American region, which today forms a narrow isthmus connecting North and South America, experienced complex geological processes involving volcanic activity, tectonic movements, and changing sea levels. During periods when sea levels dropped significantly, exposed land bridges could have facilitated dinosaur migrations. Paleontologists now believe these connections weren’t constant but appeared and disappeared multiple times throughout the Age of Dinosaurs, creating windows of opportunity for species to expand their ranges across the hemisphere.

Fossil Evidence: Tracking Ancient Travelers

The most compelling evidence for dinosaur migration comes from fossil discoveries showing similar species on both continents. For example, fossils of titanosaurs—massive, long-necked sauropods—have been found throughout both North and South America in rocks of similar age, suggesting these giants may have traveled between the continents. Similarly, certain hadrosaurs (duck-billed dinosaurs) show remarkable similarities across hemispheres. However, interpreting this evidence requires caution, as similarities could also result from parallel evolution rather than migration. Paleontologists must carefully analyze anatomical details, genetic relationships (inferred from fossil evidence), and precise dating of specimens to distinguish between dinosaurs that migrated and those that evolved similar traits independently in response to similar environmental pressures.

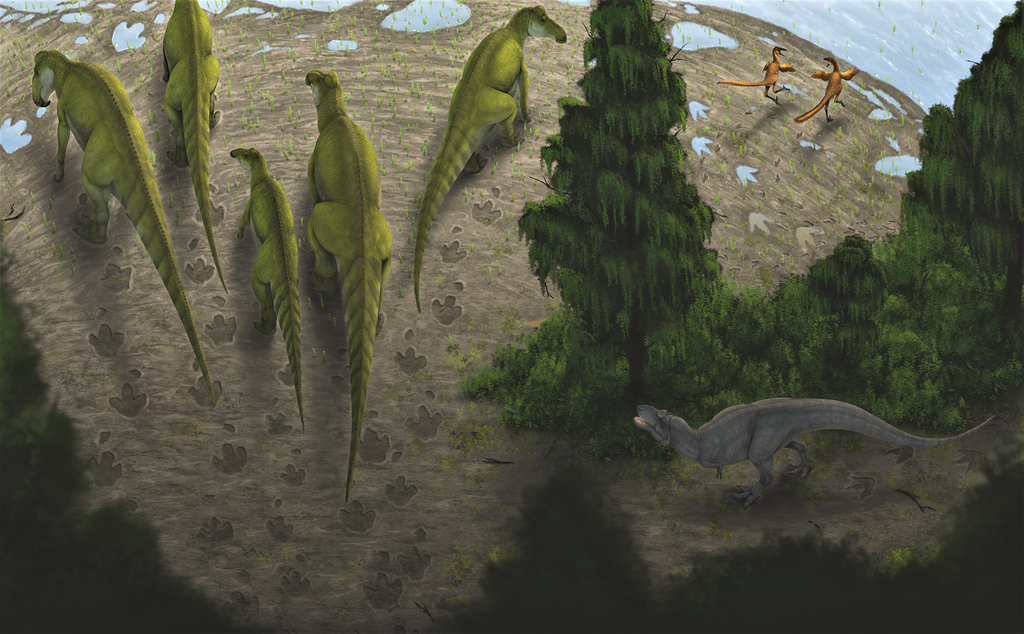

The Abelisaurid Question: Southern Specialists

Abelisaurids, a family of predatory dinosaurs that included the fearsome Carnotaurus, present a fascinating case study in dinosaur distribution. These distinctive carnivores were widespread throughout the southern continents of Gondwana, including South America, but were notably absent from North America during most of the Cretaceous period. Their absence suggests effective isolation between the Americas during crucial periods of dinosaur evolution. The distribution of these specialized predators provides evidence that migration wasn’t always possible, reinforcing the idea that land connections between North and South America were intermittent rather than constant. This pattern helps paleontologists establish timeframes when the continents were likely separated, creating distinct evolutionary paths for their dinosaur inhabitants.

Tyrannosaur Territories: Northern Dominance

Complementing the abelisaurid story is the distribution of tyrannosaurs, the famous family including Tyrannosaurus rex. These apex predators dominated North American ecosystems in the Late Cretaceous but are conspicuously absent from South American fossil records. This absence strongly suggests that during the later stages of dinosaur evolution, significant barriers prevented migration between the Americas. The geographical separation allowed different predatory dynasties to evolve in isolation—tyrannosaurs in the north and abelisaurids in the south. This pattern of distinct predator communities provides some of the strongest evidence for limited migration between the Americas during the Late Cretaceous, the final chapter in dinosaur evolution before their extinction.

Climate as a Migration Driver

Beyond physical connections, climate played a crucial role in determining dinosaur migration patterns. The Mesozoic Era witnessed dramatic climate shifts, from greenhouse conditions to cooler periods. These fluctuations would have triggered resource changes that might have pushed dinosaur populations to seek new territories. Evidence from plant fossils and geological indicators suggests that during certain periods, climate corridors existed that would have facilitated movement between the Americas. For cold-blooded dinosaurs or those particularly sensitive to temperature, these climate corridors would have been essential pathways for migration. Paleoclimatologists work alongside paleontologists to reconstruct these ancient climate patterns, helping explain not just if dinosaurs migrated, but why they might have undertaken such journeys.

The Timing Question: When Migration Was Possible

Current research suggests several “windows of opportunity” when dinosaur migration between the Americas was most likely. The Early to Middle Jurassic (about 200-165 million years ago) offered the best opportunities, as Pangaea was still largely intact. Another potential migration period occurred in the Early Cretaceous (145-100 million years ago), when geological evidence indicates possible land connections. By the Late Cretaceous (100-66 million years ago), migration appears to have become more limited, as evidenced by increasingly distinct dinosaur communities on each continent. These temporal windows help explain why some dinosaur groups show evidence of intercontinental distribution while others remained regionally isolated, creating the complex patchwork of dinosaur populations that paleontologists observe in the fossil record.

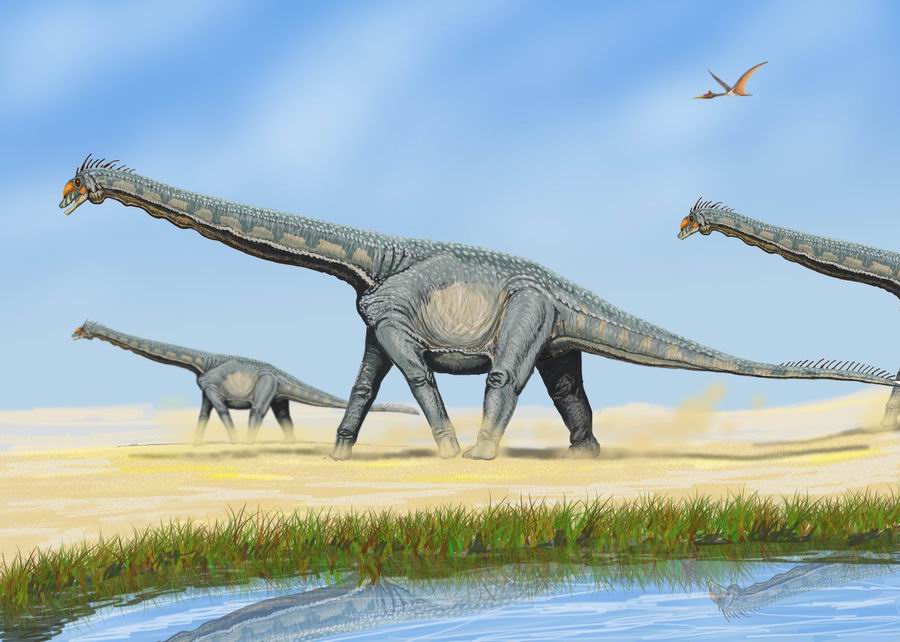

Dinosaur Swimming Abilities: Crossing Water Barriers

While land bridges provided the most obvious migration routes, some paleontologists have proposed that certain dinosaurs might have crossed narrow water channels through swimming or inadvertent rafting. Modern studies of dinosaur physiology and biomechanics suggest some species possessed swimming capabilities that might have allowed them to cross short stretches of water. Large sauropods, with their pneumatic bones and high lung capacity, might have been capable of floating and navigating across channels. Similarly, some theropods show adaptations suggesting semi-aquatic lifestyles. However, major ocean crossings would have remained insurmountable barriers for most dinosaurs, reinforcing the importance of land connections for any significant migration between the Americas.

The Alamosaurus Case Study: A Late Migrant?

Alamosaurus, a massive titanosaur from the Late Cretaceous of North America, presents one of the most intriguing cases for potential late migration. This enormous sauropod appears suddenly in the North American fossil record about 70 million years ago, with no clear ancestors on the continent. However, Alamosaurus shows remarkable similarities to South American titanosaurs. This pattern has led some paleontologists to propose that Alamosaurus or its immediate ancestors migrated northward from South America during a brief late Cretaceous land connection. The Alamosaurus case remains contentious but illustrates how specific fossil discoveries can provide evidence for migration events that broader patterns might miss. This example demonstrates the complex nature of dinosaur biogeography and the importance of examining both continental trends and individual species histories.

Modern Analogues: Learning from Today’s Migrations

To better understand dinosaur migrations, paleontologists often look to modern animal movements for insight. The Great American Biotic Interchange—when North and South American mammals exchanged territories after the formation of the Panama land bridge about 3 million years ago—provides a particularly relevant comparison. This well-documented event shows how predators, prey, and competitors responded when previously isolated ecosystems suddenly connected. Similar patterns may have occurred during dinosaur times when land bridges formed. Studies of modern animal migration drivers, including climate change, resource availability, and predator-prey dynamics, also help scientists develop models for understanding what might have prompted dinosaurs to undertake long-distance movements between continents, creating testable hypotheses that can be evaluated against the fossil evidence.

New Technologies Revealing Ancient Movements

Cutting-edge scientific techniques are revolutionizing how paleontologists investigate potential dinosaur migrations. Isotope analysis of fossil teeth and bones can reveal information about the environments where dinosaurs lived at different points in their lives, potentially tracking movements across different geological regions. Advanced CT scanning allows researchers to examine inner ear structures that might indicate migratory behaviors similar to those seen in modern birds. DNA recovery techniques, though still limited for dinosaur fossils, offer promising future avenues for establishing genetic relationships between populations. Sophisticated computer modeling also helps scientists reconstruct ancient ecosystems and simulate how dinosaur populations might have responded to changing conditions, including opportunities for migration when land bridges formed.

The Migration Legacy: Impact on Dinosaur Evolution

The question of migration between the Americas isn’t merely about dinosaur movement—it profoundly affected dinosaur evolution itself. Periods of isolation fostered endemic species with unique adaptations, while migration events introduced competition, predation, and genetic exchange that accelerated evolutionary change. The distinctive dinosaur communities that evolved in North and South America contributed to the remarkable diversity of dinosaurs worldwide. Understanding migration patterns helps explain why certain dinosaur groups thrived in some regions but not others, and how competition between previously isolated populations might have driven rapid evolutionary adaptations. The story of dinosaur migration is thus inseparable from the broader narrative of dinosaur evolution, providing crucial context for understanding the remarkable adaptive radiation of these animals across 165 million years of Earth history.

Remaining Mysteries and Future Research

Despite significant advances in understanding dinosaur distribution, major questions about migration between the Americas remain unanswered. Vast areas of both continents remain paleontologically unexplored, potentially concealing fossils that could dramatically change current theories. The timing and duration of land connections between the continents during the Mesozoic Era need further geological clarification. Questions about which dinosaur groups were more prone to migration and which environmental factors most strongly influenced migration patterns continue to challenge researchers. Future expeditions targeting crucial periods and geographical regions where the Americas might have connected could yield fossils that definitively resolve whether specific dinosaur groups migrated between the continents. The ongoing integration of paleontology with geology, climatology, and evolutionary biology promises to continue refining our understanding of these ancient movements.

Conclusion

The question of dinosaur migration between North and South America represents one of paleontology’s most fascinating frontiers. The evidence suggests a complex history of occasional connections that allowed some dinosaur groups to traverse between continents while others remained isolated. This pattern of intermittent migration helped shape the distinctive dinosaur communities that evolved on each continent, contributing to the remarkable diversity of these animals during their long reign. As research continues, each new fossil discovery and geological insight brings us closer to understanding the dynamic movement of these magnificent creatures across a changing prehistoric landscape, revealing not just where dinosaurs lived, but how they responded to a world in constant flux—a lesson with profound implications for understanding modern biodiversity and its response to environmental change.