Picture yourself standing on the shores of Lake Michigan, gazing out at those vast freshwater expanses. It’s hard to imagine that hundreds of millions of years ago, where you’re standing now wasn’t freshwater at all. This was saltwater ocean territory, a warm tropical sea where primitive sharks prowled beneath waves that stretched for thousands of miles.

We’re talking about a time so distant that trees hadn’t even evolved yet, when the continents looked nothing like they do today. Michigan sat in equatorial latitudes, covered by a shallow tropical sea during the early Paleozoic. The creatures swimming overhead weren’t the lake trout or walleye you’d expect today, but rather ancient shark relatives with bizarre features that would make modern great whites look downright ordinary. So let’s dive in.

When Michigan Was an Ocean Floor

Some 350 million years ago, this area was a warm, shallow, salt water tropical sea. The region we now call the Great Lakes was positioned near the equator, creating perfect conditions for marine life to absolutely explode in diversity. Lower Michigan was shaped like a large basin, located south of the equator, where a series of warm, shallow seas gradually filled the area then evaporated, leaving sediments behind in a process that repeated itself many times over millions of years.

This wasn’t just any ocean, mind you. Around 330 million years ago, a clear inland sea covered the Great Lakes and Ohio River regions. Think of it as a massive, bathtub-like depression that repeatedly flooded and drained as sea levels rose and fell. The limestone bedrock beneath modern Michigan cities tells this story, layer upon layer of compressed ancient sea creature remains.

The Age of Fishes Comes to the Midwest

The Devonian period, starting around 419 million years ago, not only saw the world’s first tetrapods appear, it also saw a great radiation of all fish including sharks, which is why the Devonian period is called the “Age of Fishes”. Honestly, calling it the Age of Fishes is almost an understatement. The diversity exploding through these ancient seas was mind-boggling.

Fishes, especially jawed fish, reached substantial diversity during this time, with armored placoderms beginning to dominate almost every known aquatic environment, while in the oceans, cartilaginous fishes such as primitive sharks became more numerous than in the Silurian and Late Ordovician. These weren’t just boring fish hanging around either. They were predators, prey, filter feeders, and bottom dwellers, each carved by evolution to fit their particular niche in the ecosystem.

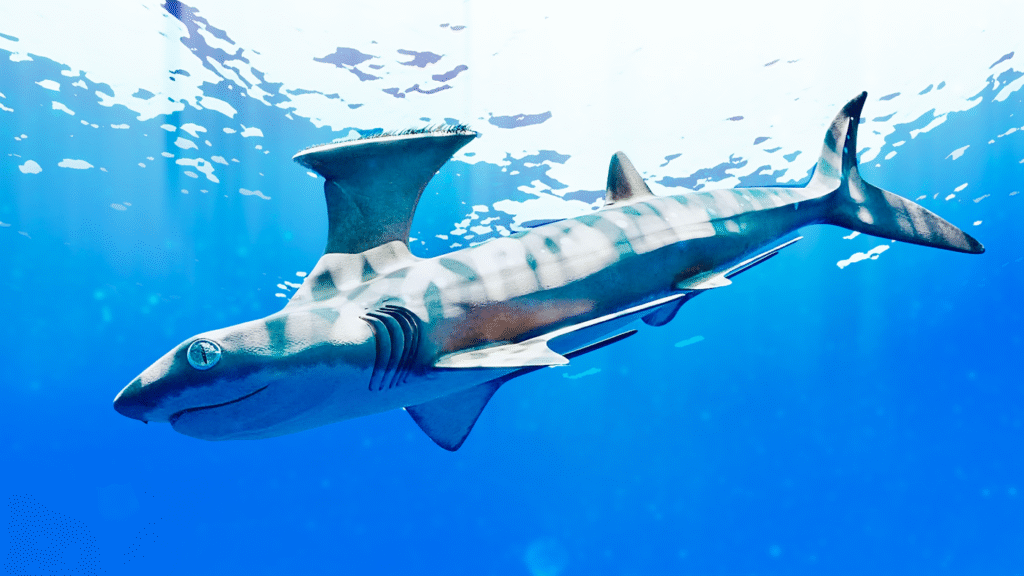

Cladoselache: The Great Lakes’ Ancient Hunter

One of the most fascinating prehistoric sharks swimming over what would become Michigan was Cladoselache. This early chondrichthyan is one of the best known, in part due to an abundance of well-preserved fossils discovered in the Cleveland Shale on the south shore of Lake Erie, with fossils so well preserved that they included traces of skin, muscle fibers, and internal organs, such as the kidneys. Let that sink in for a moment. We have fossils from creatures that lived hundreds of millions of years ago that preserve not just bones, but soft tissue.

Cladoselache was a 6-foot-long predator known for its streamlined body and aquadynamic agility, hunting bony fish and smaller sharks in the oceans that once covered North America. It looked remarkably like a modern shark, with a torpedo-shaped body built for speed. Yet despite this similarity, it lacked scales and certain reproductive structures found in later sharks, making it a fascinating evolutionary bridge species.

Shark Teeth Tell Ancient Tales

Here’s where things get really interesting for fossil hunters. Sharks swam over Michigan during the Devonian, and since shark skeletons were cartilaginous and lacked hard parts conducive to fossilization, typically only their spines and teeth remain. Cartilage just doesn’t preserve well, which means most of what we know about these ancient predators comes from their hardest parts.

Fossil shark spines found in Michigan are usually the remains of ctenacanths and cladodonts, and despite occurring so early in the fossil record, Michigan’s cladoselachian sharks closely resembled modern forms. You can actually go fossil hunting yourself in places like Alpena and Rogers City in northern Michigan. The Rockport State Recreation Area is particularly famous for yielding Devonian-era fossils, including evidence of these prehistoric sharks swimming in warm tropical waters where pine forests and Great Lakes beaches exist today.

Beyond Sharks: A Thriving Prehistoric Ecosystem

The prehistoric sharks didn’t swim alone in these ancient seas. Creatures such as crinoids, gastropods, brachiopods, cephalopods, trilobites and very primitive fish and sharks swam and lived here. Imagine a coral reef ecosystem, but weirder. Trilobites scuttled across the seafloor like armored pillbugs. Crinoids, which look like underwater flowers but are actually animals, swayed in the currents by the thousands.

Shelled marine life flourished in these salty, tropical seas, and after these animals died, their calcium-rich remains sank to the sea floor, sometimes becoming fossilized, with dozens of fossil types now found at the Straits of Mackinac, including corals, brachiopods, bryozoans, crinoids, bivalves, and trilobites. The sharks of this era were apex predators in an ecosystem so alien it would require serious mental gymnastics to fully picture it.

From Ocean to Swamp to Ice

The story doesn’t end with the Devonian seas, though. During the Early Carboniferous the sea covering Michigan began a gradual withdrawal, and sharks persisted as members of Michigan’s fish communities during the Mississippian. As sea levels dropped, the region transformed from open ocean to coastal swamps teeming with primitive plants.

Some shark species even adapted to freshwater environments during this transition period. Research on fossil sites in Illinois, not far from the Great Lakes region, revealed that certain ancient sharks actually migrated between freshwater and saltwater, using coastal areas as nurseries. Eventually, the Paleozoic era ended with a catastrophic extinction event, glaciers came and went multiple times, carving out the Great Lakes basins we know today, and those ancient tropical seas became a distant memory preserved only in stone.

Finding Your Own Piece of Prehistoric Ocean

The remarkable thing is you don’t need a time machine or a submarine to connect with this ancient world. A visit to northeast Michigan’s coastline offers opportunities to explore life of the ancient oceans that existed more than 350 million years ago in the Great Lakes region, with opportunities to find and explore, firsthand, fossils of these ancient Devonian Seas. Places like the Besser Museum and the Lafarge Fossil Park in Alpena welcome visitors who want to hunt for traces of these prehistoric sharks.

At Rockport State Recreation Area, you can spend hours in the abandoned limestone quarry finding nearly every type of Devonian Era fossil you might imagine, with large Petoskey stones always a prized find and the coastline also known for amazing gastropod finds. Every piece of limestone you pick up potentially contains the compressed remains of creatures from that ancient tropical sea. Next time you’re holding a Petoskey stone, Michigan’s state stone made from fossilized coral, remember you’re literally holding a piece of that prehistoric ocean in your hand. It’s a tangible connection to a world where sharks ruled seas that no longer exist, swimming over land that would eventually become your home.

Did Michigan’s prehistoric ocean reveal secrets you never expected? What surprises you most about the Great Lakes’ ancient past?