Picture stepping outside your door in Kansas and diving straight into warm, tropical waters teeming with massive marine reptiles and ancient sea creatures. This isn’t fantasy. For tens of millions of years during the Cretaceous Period, most of what we now call the Great Plains lay beneath a vast inland sea that stretched from the Arctic Ocean to the Gulf of Mexico. This ancient waterway, known as the Western Interior Seaway, existed from approximately 100 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous to about 66 million years ago, connecting the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean.

You’re about to discover how this forgotten ocean shaped everything from the fossil record to the very landscape beneath your feet. The geological evidence tells an incredible story of climate, life, and planetary forces that split an entire continent in two. Let’s dive into the depths of North America’s hidden past.

The Continental Split That Changed Everything

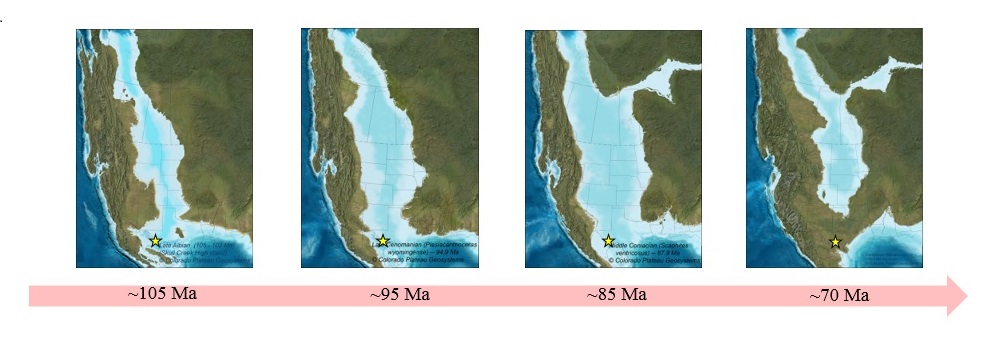

The Western Interior Seaway was a large inland sea that existed roughly over the present-day Great Plains of North America, splitting the continent into two landmasses, Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east. At its largest extent, the seaway was approximately 2,500 ft (760 m) deep, 600 mi (970 km) wide and over 2,000 mi (3,200 km) long.

This massive waterway didn’t just appear overnight. During the Cretaceous period, the ancient Farallon and Kula tectonic plates were in the process of subducting beneath the North American Plate. This caused the overlying land to warp and form a large back-arc basin. The continental crust literally bent under the immense tectonic forces, creating a depression that oceanic waters couldn’t resist filling.

Formation Through Tectonic Forces

The seaway’s birth story reads like a geological thriller. The earliest phase of the seaway began in the mid-Cretaceous when an arm of the Arctic Ocean transgressed south over western North America; this formed the Mowry Sea, so named for the Mowry Shale. Meanwhile, from the south, waters from what would become the Gulf of Mexico crept northward.

In time, the southern embayment merged with the Mowry Sea in the late Cretaceous, forming a completed seaway, creating isolated environments for land animals and plants. The result was North America transformed into two separate landmasses for roughly half the Cretaceous Period. For about half of the Cretaceous Period, North America was essentially two islands, Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east.

A Shallow Tropical Paradise

You might imagine this ancient ocean as a deep, dark abyss, but reality was quite different. At its deepest, it may have been only 800 or 900 metres (2,600 or 3,000 ft) deep, shallow in terms of seas. This shallow depth meant that the Sun’s life-giving rays touched a significant portion of the water column, and so, the ocean teemed with all sorts of marine creatures.

Widespread carbonate deposition suggests that the seaway was warm and tropical, with abundant calcareous planktonic algae. The climate was nothing like today’s continental interior. The Western Interior Seaway was present during one of the warmest periods on Earth, when the poles were devoid of ice and sea levels were 500 feet higher.

The Incredible Diversity of Marine Giants

The Western Interior Seaway was home to some of the most spectacular marine life Earth has ever seen. Mosasaurs growing up to 18 meters (59 feet) long, ichthyosaurs, and plesiosaurs dominated the waters. These weren’t your typical ocean dwellers. When they were alive, mosasaurs could reach lengths of up to 59 feet, which is roughly the length of a bus!

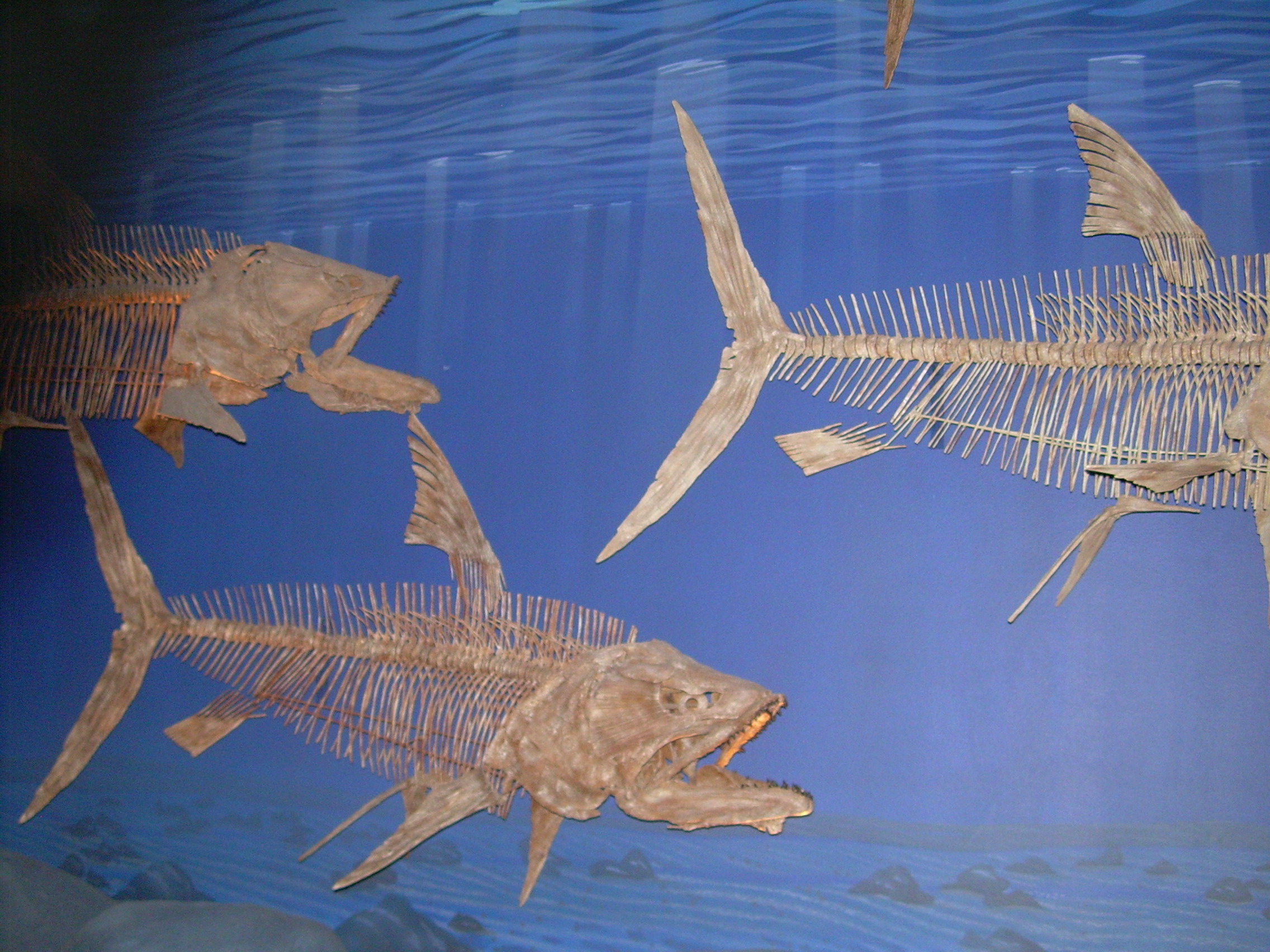

Advanced bony fish including Pachyrhizodus, Enchodus, and the massive 5-meter long Xiphactinus, a fish larger than any modern bony fish, swam in these waters. The seaway was home to early birds, including the flightless Hesperornis that had stout legs for swimming through water and tiny wings used for marine steering rather than flight. Above the surface, pterosaurs soared on massive wingspans, completing this alien ecosystem.

The Fossil Record’s Greatest Treasure Trove

What makes the Western Interior Seaway truly remarkable for science is its extraordinary fossil preservation. Conditions on the ocean floor were periodically anoxic (with little or no oxygen). Because of this, dead animals that sank to the bottom often decomposed slowly, favoring their preservation as fossils.

Sometimes regional anoxia led to the exceptional preservation of soft tissues. For instance, fossilized remains of cartilaginous sharks can be found, as can skin impressions of mosasaurs, and completely articulated vertebrate skeletons. In Kansas, the Niobrara Formation has produced thousands of spectacular specimens, including the famous “fish within a fish” – a 13-foot Xiphactinus that died after swallowing a 6-foot Gillicus whole.

Ancient Climate Revealed Through Geological Evidence

The rocks tell us remarkable stories about ancient climates. During the Cretaceous Thermal Maximum, atmospheric carbon dioxide levels rose to over 1,000 parts per million compared to the pre-industrial average of 280 ppm. Rising carbon dioxide resulted in a significant increase in the greenhouse effect, leading to elevated global temperatures.

Subsequent warming reached a peak in the Turonian, when sea surface temperatures in equatorial and high-latitude regions exceeded 36° C and 20° C, respectively. These temperatures seem almost unimaginable today. Temperatures were so high that champsosaurs (crocodile-like reptiles) lived as far north as the Canadian Arctic, and warm-temperature forests thrived near the South Pole.

Ammonites: The Spiral Shell Chronicles

Among the most scientifically valuable fossils from the Western Interior Seaway are ammonites, those distinctive spiral-shelled creatures that dominated Cretaceous seas. These sea creatures included invertebrates such as mollusks, ammonites, squid-like belemnites, and plankton including coccolithophores that secreted the chalky platelets that give the Cretaceous its name.

Ammonoids are excellent index fossils, and they have been frequently used to link rock layers in which a particular species or genus is found to specific geologic time periods. Through the use of invertebrate index fossils, Collignoniceras (ammonite) and Rotalipora (foraminiferan), paleontologists determined that Big Bend mosasaur fossils represented the oldest occurrence of mosasaurs in North America! The predator-prey relationships are even preserved in stone. Evidence of medium-sized mosasaur bites on ammonite shells shows triangular bite marks corresponding to upper and lower jaws.

The Gradual Disappearance

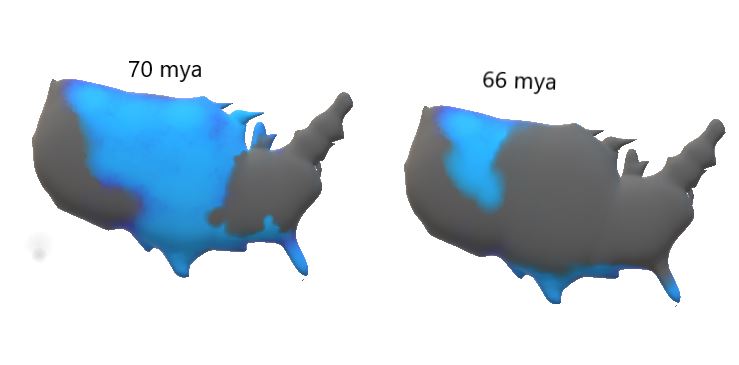

The end of this magnificent seaway came not through catastrophe, but through slow geological forces. Eventually, the seaway closed off at the end of the Cretaceous and gradually disappeared due to regional uplift and mountain-building on the western side of North America. In the early stages of the orogeny, the rising ancestral Rocky Mountains provided sediment to the remains of the Western Interior Seaway. By the end of the Cretaceous period about 66 million years ago, the seaway was nearly gone. The now-exposed terrain provided the foundation for the topography of the Interior Plains.

Abrupt global cooling, likely triggered by a massive asteroid, not only doomed the dinosaurs but the ocean as well. Over millions of years, the waters dwindled and evaporated to be locked up in far-off frozen glaciers.

Modern Remnants of an Ancient World

You don’t need a time machine to witness evidence of this ancient ocean. Traces of the Western Interior Seaway can still be found in marine deposits throughout the United States ranging from New Mexico to North Dakota, including famous ones such as the Pierre Shale and the Austin Chalk. Some of the most notable outcrops are the Monument Rocks of Western Kansas.

In Gove County, Kansas, the Monument Rocks jut magnificently seventy feet up from what is otherwise a mostly flat and featureless terrain. The remarkable earthen structures are made of carbonate rocks which formed on the seafloor during the ocean’s existence spanning tens of millions of years. Standing near the formations, one can almost imagine standing on the prehistoric seabed back in the Cretaceous Period.

Conclusion

The Western Interior Seaway represents one of Earth’s most dramatic transformations, when tectonic forces literally split a continent and created conditions unlike anything in our modern world. The fossil treasures it left behind continue to reshape our understanding of ancient climates, marine ecosystems, and the dynamic nature of our planet.

This hidden ocean reminds us that the landscapes we consider permanent are merely snapshots in geological time. The next time you drive across the Great Plains, remember that you’re traveling through the bed of an ancient sea that once hosted some of the most magnificent creatures our planet has ever known. What other secrets might the rocks beneath our feet still be hiding?