Have you ever wondered what it was like when massive beasts roamed freely across continents that looked nothing like the maps we know today? Prehistoric mammals weren’t just bigger versions of today’s animals. They were pioneers, adventurers, and survivors who crossed land bridges that no longer exist and navigated landscapes that have vanished beneath the waves. Their journeys tell us something profound about survival, adaptation, and the fragile dance between life and a changing planet.

These ancient creatures didn’t have GPS or migration guides. Yet somehow they found their way across thousands of miles, following invisible pathways written in their instincts. What drove a woolly mammoth to walk the equivalent distance of circling Earth twice in a single lifetime? Why did horses disappear from their birthplace only to return thousands of years later? The answers lie buried in tusks, teeth, and bones that scientists are only now learning to read like ancient diaries.

When Mammoths Walked Further Than We Ever Imagined

The woolly mammoth named Kik lived approximately 17,100 years ago in what is now Alaska and walked roughly twice the circumference of the earth during his lifetime. Think about that for a moment. This single animal covered distances that would put most modern road trips to shame. Scientists discovered this astonishing fact by analyzing the isotopes preserved in Kik’s tusk, which acted like a chemical diary recording every place he’d been.

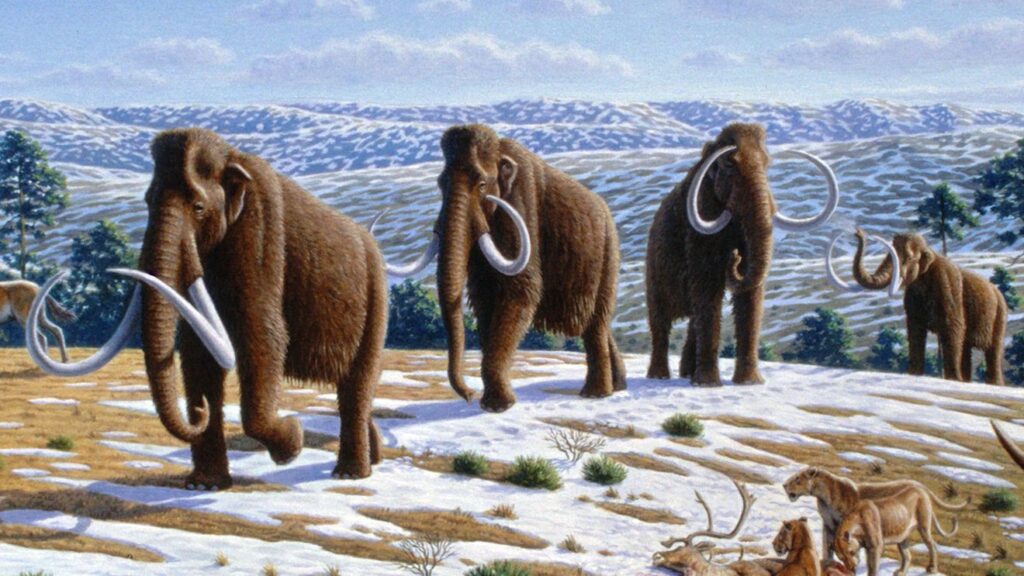

Young Kik made regular back-and-forth journeys across a 250-mile stretch of steppe grassland between the Brooks Range and the Alaska Range. This wasn’t random wandering. These creatures followed patterns, possibly tracking seasonal vegetation or avoiding predators. The habitat where woolly mammoths lived stretched across northern Asia, many parts of Europe, and the northern part of North America during the last ice age.

Honestly, the more we learn about mammoth movements, the more impressive they become. These weren’t sedentary grazers content to stay in one valley. Whole mitochondrial genome sequences spanning over 50,000 years have shown that mammoths not only migrated from Asia to North America, but back again. The Bering land bridge became their highway between continents.

The Epic Horse Odyssey Nobody Talks About

The very first horses evolved on the North American grasslands over 55 million years ago, then deserted North America and migrated across the Bering land bridge into what is now Siberia. Let that sink in. Horses are as American as you can get, evolutionarily speaking. Yet they abandoned their homeland entirely.

About 8000 BCE, succumbing to climate change and human hunters, horses completely vanished from North America. For thousands of years, the continent that gave birth to horses had none. Ancient horses migrated back and forth between North America and Asia many times in response to changes in climate during the Late Pleistocene. This wasn’t a one-way trip but rather a complex dance of populations moving, interbreeding, and adapting.

What’s really fascinating is how horses adapted to survive these journeys. When melting ice sheets submerged the land bridge and transformed the landscape from dry grasslands to boreal forests and swamps, the new conditions were less hospitable to grazing animals like horses, and they couldn’t migrate to more favorable locations, which led to a sharp decline in their population. Migration corridors weren’t just nice to have. They were survival itself.

Lost Continents and Ancient Highways Nobody Remembers

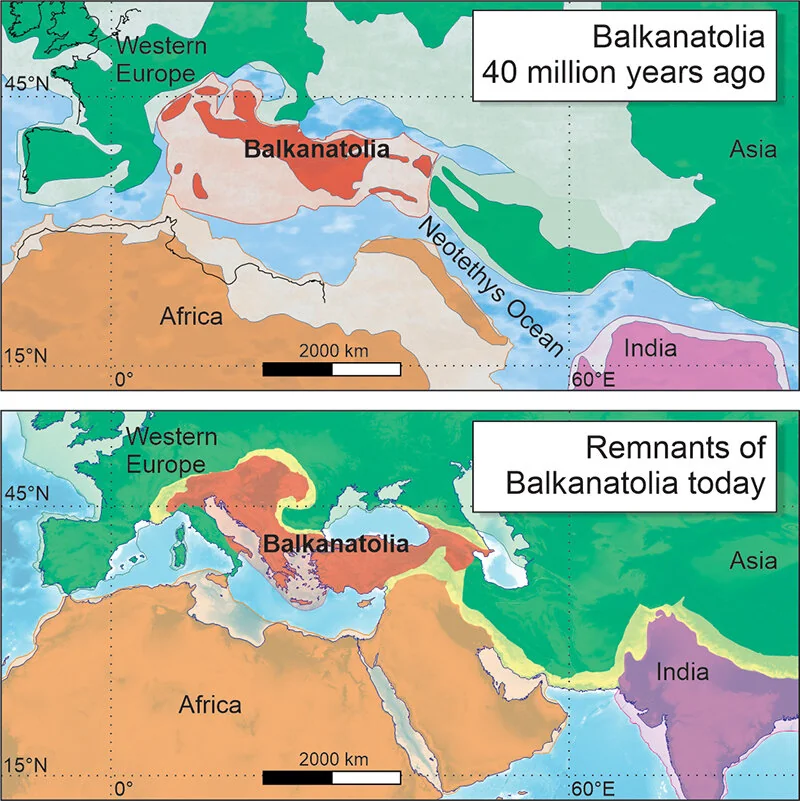

Here’s something that sounds like science fiction but isn’t. A low-lying landmass called “Balkanatolia” allowed mammals all over Asia to cross into Europe, leading to an abrupt and extensive extinction event roughly 34 million years ago. Entire landmasses that once connected continents have disappeared, taking their stories with them.

Paleolithic hunter-gatherers entered North America from the North Asian Mammoth steppe via the Beringia land bridge, which had formed between northeastern Siberia and western Alaska due to the lowering of sea level during the Last Glacial Maximum. This land bridge wasn’t some narrow strip. It was a massive grassland ecosystem in its own right, supporting entire populations of megafauna.

The geological lottery of ice ages opened and closed these migration routes repeatedly. By 21,000 years BP, the Cordilleran and Laurentide ice sheets coalesced east of the Rocky Mountains, closing off a potential migration route into the center of North America, while alpine glaciers in the coastal ranges and the Alaskan Peninsula isolated the interior of Beringia from the Pacific coast. Mammals had to time their journeys perfectly or risk being trapped.

Saber-Toothed Cats: The Silent Stalkers of Two Continents

Smilodon lived in the Americas during the Pleistocene to early Holocene epoch, from 2.5 million years ago to at latest 8,200 years ago. These iconic predators weren’t just sitting around waiting for dinner to wander by. They moved with their prey across vast distances.

Saber-toothed cats roamed North America and Europe throughout the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, and by Pliocene times they had spread to Asia and Africa, with sabre-toothed cats also present in South America during the Pleistocene. Their distribution tells a story of successful adaptation and opportunistic range expansion.

What I find particularly striking is how these predators tracked their prey. The habitat of North America varied from subtropical forests and savannah in the south to treeless mammoth steppes in the north, supporting large herbivores such as horses, bison, antelope, deer, camels, mammoths, mastodons, and ground sloths. Saber-toothed cats followed this moving buffet across continents.

Ground Sloths: The Unexpected Travelers

Giant ground sloths don’t exactly scream “long-distance traveler” when you picture them. Yet they were remarkably successful migrants. Sloths represented one of the more successful South American groups during the Great American Interchange after the connection of North and South America during the late Pliocene, with a number of ground sloth genera migrating northward.

Megalonychid and mylodontid sloths had migrated into North America by the Late Miocene around 10 million years ago, and during the Pliocene and Pleistocene, as part of the Great American Interchange, additional lineages of sloths migrated into Central and North America. These weren’t quick sprints. These were multigenerational journeys taking thousands of years.

Sloths started in South America but migrated north when the continents connected about 2.5 million years ago, with fossils found from Brazil all the way to South Carolina. Some species even made it to the Caribbean islands, swimming or rafting to isolated landmasses. It’s hard to say for sure, but imagine the determination required for a creature that slow to colonize an entirely new continent.

Climate Change as the Ultimate Migration Driver

Let’s be real about what really controlled these ancient migrations: climate. Around 3 million years ago, mammoths spread into the northern hemisphere and began a process of transformation leading to the highly-specialised woolly mammoth of the late ice age, adapted to cold, treeless environments and a diet of grass. Environment shaped evolution, and evolution enabled migration.

The series of fossils tracks the change in anatomy resulting from a gradual drying trend that changed the landscape from a forested habitat to a prairie habitat, with early horse ancestors originally specialized for tropical forests while modern horses are now adapted to life on drier land. Animals didn’t just move to new places. They transformed themselves to survive in those new environments.

As temperatures warmed and ice sheets retreated, the environments that ground sloths and other megafauna once thrived in changed, and as a result many populations started to collapse. Migration only works when there’s somewhere viable to migrate to. When the entire climate system shifts too quickly, even the greatest travelers run out of options.

The Extinction Mystery: Why Did the Journeys End?

When humans reached North America 13,000 years ago, 78 species that weighed over a ton vanished in the terminal Pleistocene megafauna extinction. The end of these magnificent migration patterns coincided suspiciously with human arrival. Coincidence? Probably not.

Over 30 living species of ground sloths during the Late Pleistocene abruptly became extinct on the American mainland around 12,000 years ago simultaneously with the majority of other large animals, with their extinction posited to be the result of hunting by recently arrived humans and climate change. The debate continues about which factor mattered more, but both certainly played roles.

Maintenance of mobility by megafaunal species such as mammoth would have been increasingly difficult as the ice age ended and the environment changed at high latitudes. These animals needed vast territories and reliable migration routes. As landscapes fragmented and human populations expanded, the ancient highways closed forever. The great journeys that had sustained these species for millions of years simply became impossible.

Conclusion

The migration patterns of prehistoric mammals reveal a world far more dynamic and interconnected than most of us imagine. These weren’t just animals wandering aimlessly. They were following ancient pathways encoded in their biology, responding to environmental cues we’re only beginning to understand through modern science. Mammoths that circled the planet, horses that played continental hopscotch, saber-toothed cats that tracked prey across hemispheres, and even sluggish ground sloths that somehow colonized entire continents – each tells us something vital about resilience, adaptation, and the fragility of existence.

Today, as our climate shifts once again and migration corridors vanish beneath roads and cities, maybe these ancient stories hold lessons we can’t afford to ignore. The prehistoric mammals couldn’t survive when their pathways closed. Modern species face the same predicament. The difference is that this time, we have the knowledge and the power to maintain those crucial connections. Whether we choose to do so remains to be seen.

What do you think drove these incredible journeys most – necessity or opportunity? And what would our own world look like if these magnificent migrants still roamed wild?