When you think about the challenges faced by your Stone Age ancestors, you probably imagine battles with woolly mammoths or harsh winters in cave shelters. Yet there was an enemy far more persistent and insidious lurking in their daily lives. These tiny terrors didn’t roar or charge, they simply bit, burrowed, and bred, turning survival into a constant struggle. The pests of prehistoric times were relentless companions that shaped how humans lived, ate, and even migrated.

Life thousands of years ago wasn’t just about hunting and gathering. It was also about coexisting with creatures that saw humans as perfect hosts or food sources. These weren’t your modern household annoyances that can be dealt with using a quick spray or trap. Stone Age pests were embedded in the very fabric of daily existence, affecting health, food security, and settlement patterns in ways that still echo through archaeological discoveries today.

Head Lice: The Unwanted Inheritance From Our Ancestors

Certain organisms adapted to your prehominin ancestors and have been problems ever since, including head lice, pinworms, and yaws. These parasites weren’t just a minor irritation. They were constant companions that likely transferred from one generation to the next with remarkable efficiency. Head lice and body lice are among the oldest permanent ectoparasites of humans, making them one of the most enduring relationships in our species’ history.

Honestly, imagine living in close quarters within a cave or shelter with no way to properly cleanse yourself or your clothing. Lice and nits have been found in textiles, hair and combs excavated from archaeological sites, proving that these pests were so prevalent that traces remain millennia later. Your Stone Age relatives had no shampoos or fine-tooth plastic combs to combat these bloodsuckers. They probably dealt with the constant itching and irritation as just another fact of life, one that followed them wherever they wandered.

Intestinal Worms: Hidden Invaders of the Gut

Whipworm (Trichuris trichiura) and roundworm (Ascaris lumbricoides) date respectively to the Neolithic and Bronze Age, showing that intestinal parasites plagued humans from the earliest periods of settlement. These weren’t simple discomforts. They were silent thieves, stealing nutrients from the food your ancestors worked so hard to gather or hunt. Living inside human intestines, they absorbed what little sustenance was available and weakened their hosts over time.

The real kicker is how these parasites spread. Infections spread through contact with the host’s poop, since the poop contains the eggs. Without modern sanitation or even basic knowledge of hygiene, Stone Age communities unknowingly passed these parasites from person to person. The eggs could survive in soil for extended periods, contaminating food sources and water. It’s hard to say for sure, but this cycle probably made certain settlements more dangerous than the wilderness itself.

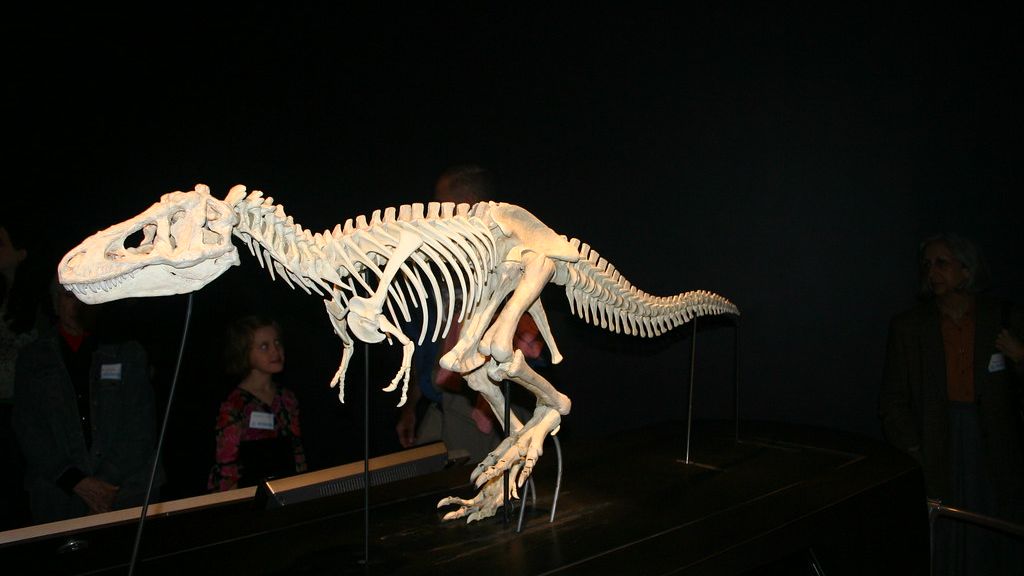

The Rodent Problem: Thieves at the Grain Storage

Stone Age farmers in southern France were fighting mice and insects feasting on their supplies 4,000 years ago, and researchers found bones of more than 40 wood mice in one prehistoric well. This discovery reveals a frustrating reality for early agricultural societies. You could spend seasons growing and harvesting crops only to have rodents decimate your winter stores. Rodents serve as agricultural pests and as vectors and reservoirs of disease, making them doubly dangerous to ancient populations.

Here’s the thing about rodents in prehistoric times: they were incredibly adaptive. Scientists believe farmers threw the mice they managed to catch into an abandoned well nearby, suggesting a deliberate effort to control these pests. Yet catching mice one by one was probably an exhausting and largely futile exercise. The rodents bred faster than humans could eliminate them, and their constant gnawing on stored food meant the difference between survival and starvation during lean months.

Grain Weevils and Storage Pests: The Invisible Food Destroyers

The transition to agriculture brought unexpected consequences. The grain weevil feeds on cereal grains including wheat, oats, rye and barley, and can cause substantial damage to harvested store grains with the potential to drastically decrease crop yields. These tiny insects were probably invisible threats to the untrained eye, yet their impact was devastating. By the time your Neolithic ancestors noticed something was wrong, entire stores could be compromised.

What makes this particularly cruel is the sheer reproductive capacity of these pests. One pair of weevils can produce up to 6,000 offspring per year. Let’s be real: without sealed containers or pesticides, there was virtually no way to stop an infestation once it began. The very innovation that allowed humans to settle in one place and build communities also created perfect breeding grounds for pests that specialized in exploiting stored food.

Mosquitoes and Disease Vectors: Deadly Bites in the Paleolithic

Zoonoses that could have infected ancient hunter-gatherers include vector-borne diseases transmitted by flies, mosquitoes, fleas, midges, and ticks. These bloodsucking insects weren’t just annoying; they were potential death sentences. Certain lice were ectoparasites as early as the Oligocene, and prehumans of the early Pliocene probably suffered from malaria, since the Anopheles mosquito necessary for transmission of the disease evolved by the Miocene era.

I know it sounds crazy, but mosquitoes have been killing humans for longer than we’ve been anatomically modern. On average, mosquitoes are estimated to kill 725,000 people per year by transmitting deadly diseases, and as a group, mosquitoes have been around for nearly 125 million years. Your Stone Age ancestors had no understanding of how diseases spread, no nets to protect themselves while sleeping, and no drainage systems to eliminate breeding grounds. Every bite was a potential encounter with a parasite that could weaken or kill.

Fish Tapeworms and Waterborne Parasites: The Price of Aquatic Resources

The earliest evidence for fish tapeworm, Echinostoma worm, and giant kidney worm in Britain was found in Bronze Age remains, and these parasites are spread by eating raw aquatic animals such as fish, amphibians and molluscs. For communities living near water sources, fish and shellfish were vital protein sources. Yet consuming these foods without cooking them properly came with hidden dangers. One dog coprolite contained eggs of fish tapeworm, indicating it had previously eaten raw freshwater fish to become infected.

The problem wasn’t limited to one species of parasite. Finding eggs of capillariid worms in both human and dog coprolites indicates that people had been eating the internal organs of infected animals. Stone Age populations were resourceful, using every part of an animal to avoid waste. This practical approach, however, exposed them to parasites that thrived in the intestinal tissues of their prey. The very survival strategies that kept communities fed also made them vulnerable to debilitating infections.

Fleas and the Plague Connection: Ancient Threats We’re Still Uncovering

Seven people living 2800 to 5000 years ago in Europe and Asia were infected with Yersinia pestis, the bacteria that causes the plague, and these samples ranged from Bronze Age skeletons that dated back as early as 4800 years ago. This bacterium, though not as deadly in its ancient form as it later became, still posed significant risks. Bronze Age bacteria evolved from a less virulent species that may have spread more like the flu, tuberculosis, or AIDS than the bubonic plague transmitted through flea bites.

What’s fascinating here is how pests and disease evolved together. Recent research demonstrates that human body lice are more efficient transmitters of plague than previously thought, and researchers wondered whether lice might have provided an additional transmission route. Your Stone Age ancestors faced an invisible enemy that could spread through multiple pest vectors. They had no concept of bacteria or transmission routes, only the terrifying reality of people mysteriously falling ill and dying.

Living With Stone Age Pests: An Endless Battle

Grass bedding was arranged on layers of ash, which serves as a deterrent to pests because insects can’t crawl through its fine texture, it dehydrates them and it can also block their breathing and biting. This shows remarkable ingenuity. Your ancestors weren’t helpless victims; they developed strategies to combat pests using the materials available to them. Remains from the camphor bush were found on top of grass bedding, and this plant is still used as a way to deter insects in rural areas of East Africa.

Yet despite these clever adaptations, the battle was never truly won. Pests shaped where people could live, what they could eat, and how long they survived. The transition from nomadic hunting to settled agriculture only intensified pest problems, creating concentrated food stores and dense human populations that pests exploited ruthlessly. These tiny creatures were architects of human misery in ways that apex predators could never match.

Stone Age pests weren’t just background noise in the struggle for survival. They were active participants in shaping human evolution, migration patterns, and the development of early technology. From the lice that hitched rides on our ancestors as they spread across continents to the grain weevils that threatened the agricultural revolution itself, these creatures left an indelible mark on human history. Understanding their impact helps us appreciate not just the ingenuity of our ancestors, but also the constant challenges they faced in a world where even the smallest creatures posed monumental threats. What do you think you would have found most unbearable about Stone Age pest life?