When you think of dinosaurs, your mind probably conjures up images of razor-sharp teeth and massive predators hunting their prey. But what if I told you that some of the most fascinating dinosaurs were actually picky eaters who preferred delicate flowers, or that others had to swallow stones to digest their meals? The world of prehistoric dining was far stranger than Hollywood ever imagined.

Stone-Swallowing Giants: When Rocks Became Dinner Companions

Picture this: you’re a massive long-necked dinosaur, and your breakfast consists of hundreds of pounds of tough, fibrous plants. How do you break down all that vegetation without proper grinding teeth? The answer lies in one of nature’s most ingenious solutions – gastroliths, or stomach stones.

Sauropods like Brontosaurus and Diplodocus deliberately swallowed smooth, polished rocks that acted like internal mills in their stomachs. These stones, sometimes weighing several pounds each, would tumble around in their digestive system, grinding up plant matter into digestible pulp. It’s like having a rock tumbler permanently installed in your belly.

Scientists have discovered these stomach stones in fossilized remains, often finding them clustered together in what would have been the dinosaur’s abdominal cavity. The stones show distinct wear patterns from constant grinding, proving that these ancient giants had mastered the art of mechanical digestion millions of years before humans invented the mortar and pestle.

The Flower-Powered Ceratopsians: Nature’s First Florists

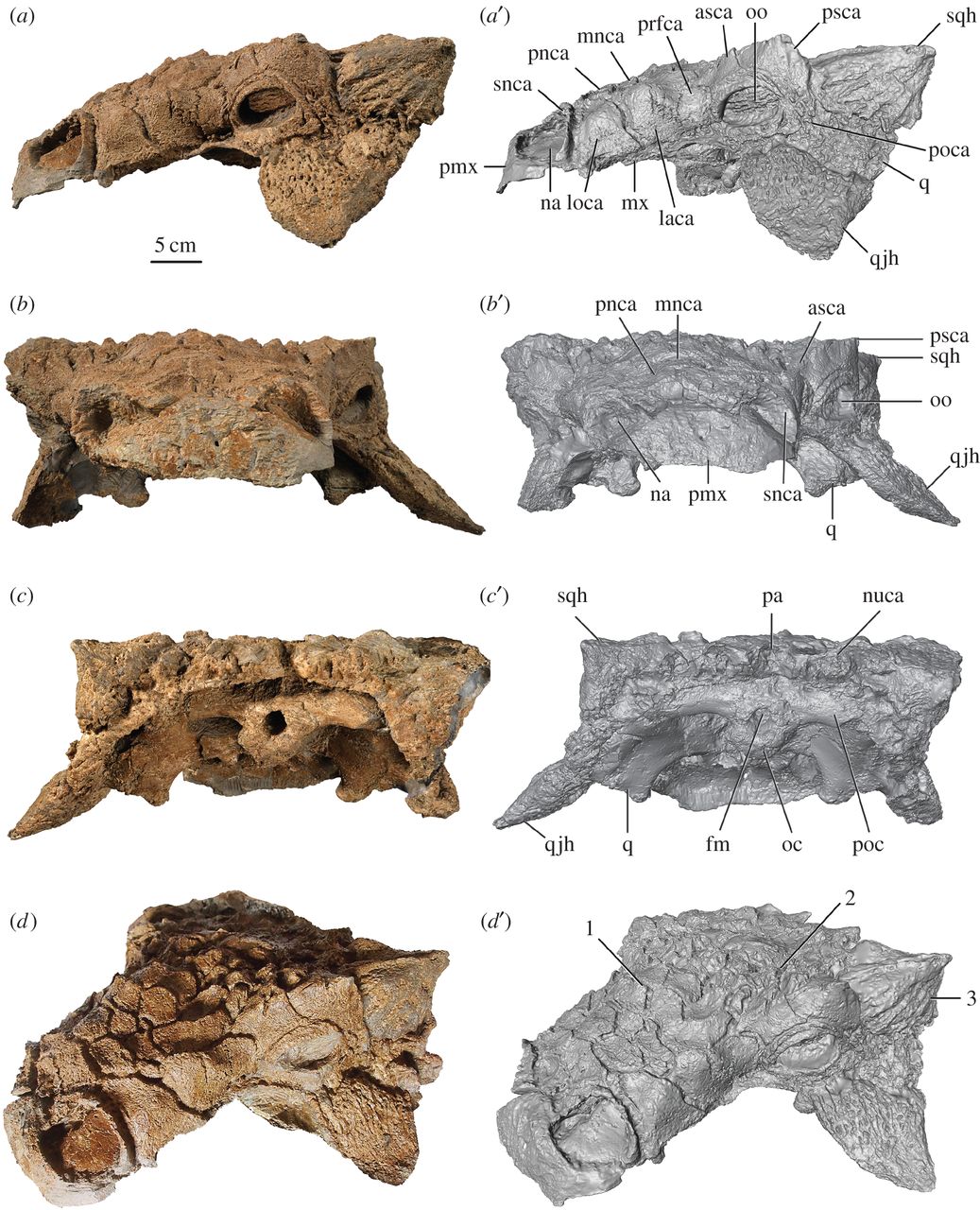

Before bees became the poster children for flower pollination, massive horned dinosaurs were already making their living as prehistoric gardeners. Ceratopsians like Triceratops weren’t just randomly munching on plants – they were specifically targeting flowering plants that had recently evolved during the Cretaceous period.

These heavily armored herbivores developed specialized beak-like mouths perfectly designed for nipping off delicate flower heads and young shoots. Their powerful jaw muscles could generate tremendous force, allowing them to process even the toughest plant material. It’s quite remarkable to imagine a three-ton dinosaur delicately selecting the choicest blooms like a sommelier choosing wine.

The relationship between flowering plants and ceratopsians was likely mutually beneficial. As these dinosaurs fed on flowers, they inadvertently helped spread pollen and seeds across vast distances, playing a crucial role in the evolutionary success of angiosperms that still dominate our planet today.

Fish-Eating Spinosaurus: The Crocodile That Walked on Land

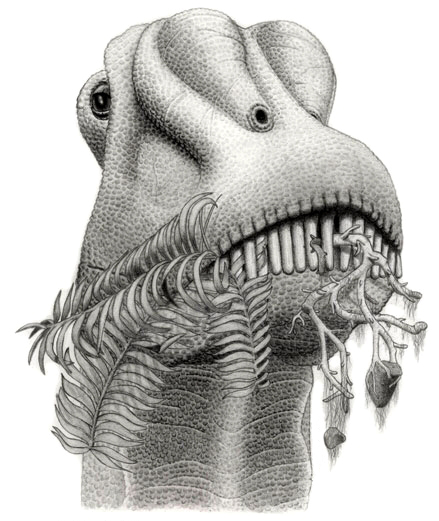

Forget everything you thought you knew about Spinosaurus from movies – this massive predator was actually more like a gigantic, bipedal crocodile than a typical land-based dinosaur. Recent discoveries have revealed that Spinosaurus spent much of its time in rivers and coastal waters, hunting fish with the precision of a modern heron.

This aquatic giant possessed a elongated, crocodile-like snout lined with cone-shaped teeth perfect for catching slippery fish. Its massive sail-like back fin likely helped it navigate through water while hunting. Scientists have found Spinosaurus teeth embedded in the fossilized remains of large prehistoric fish, providing concrete evidence of its piscivorous lifestyle.

The discovery of Spinosaurus’s fish-eating habits revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur diversity. Here was a predator that could rival T. rex in size but chose to make its living in an entirely different ecological niche, proving that the age of dinosaurs was far more complex than we previously imagined.

Bone-Crushing Majungasaurus: The Cannibal King

In the predator-eat-predator world of Cretaceous Madagascar, Majungasaurus took survival to a disturbing new level. This theropod dinosaur didn’t just hunt other species – it regularly feasted on members of its own kind, making it one of the few confirmed cannibalistic dinosaurs in the fossil record.

Paleontologists discovered Majungasaurus bones bearing distinctive tooth marks that perfectly matched the predator’s own dental pattern. The evidence was so compelling that there was no doubt: these dinosaurs were eating each other. The bite marks showed that they weren’t just scavenging already-dead relatives – they were actively hunting and killing other Majungasaurus.

This cannibalistic behavior might seem shocking, but it actually makes ecological sense. Madagascar was an island with limited resources, and large predators like Majungasaurus would have faced intense competition for food. When prey became scarce, turning on their own species became a matter of survival.

Egg-Stealing Oviraptor: The Misunderstood Nest Raider

Few dinosaurs have suffered from worse public relations than Oviraptor, whose name literally means “egg thief.” For decades, paleontologists believed this bird-like dinosaur survived by raiding the nests of other dinosaurs and feasting on their eggs, based on fossils found near what appeared to be stolen clutches.

However, modern analysis revealed a shocking plot twist: Oviraptor wasn’t stealing eggs at all. The fossilized remains showed adult Oviraptors brooding over their own nests, protecting their young just like modern birds do. These devoted parents were actually incubating their eggs when they were suddenly buried by sandstorms or other natural disasters.

The real diet of Oviraptor was far more varied than initially thought. These dinosaurs had powerful, beak-like jaws that could crack open hard-shelled mollusks, crush tough plant material, and even catch small animals. They were opportunistic omnivores that adapted their diet based on seasonal availability of food sources.

Blood-Sucking Ubirajara: The Vampire Dinosaur

Deep in the forests of Cretaceous Brazil lived one of the most peculiar dinosaurs ever discovered – Ubirajara, a small theropod with an appetite for blood. This crow-sized predator possessed needle-like teeth perfectly designed for piercing skin and accessing the blood vessels of larger animals.

Unlike modern vampires of folklore, Ubirajara likely didn’t drain its victims completely. Instead, it probably fed like a prehistoric mosquito, taking small blood meals from larger dinosaurs while they slept or rested. The dinosaur’s lightweight build and sharp claws would have made it an excellent climber, allowing it to access sleeping giants from above.

The discovery of Ubirajara’s blood-sucking lifestyle opened up entirely new possibilities for dinosaur ecology. It showed that even in the age of giants, there was room for highly specialized micro-predators that exploited unique feeding niches unavailable to larger dinosaurs.

Shellfish-Specialized Paralititan: The Prehistoric Oyster Shucker

While most sauropods were content munching on ferns and conifers, Paralititan developed a sophisticated taste for shellfish that would make any modern seafood lover envious. This massive dinosaur lived in the coastal regions of ancient Egypt, where it specialized in harvesting mollusks from tidal pools and shallow marine environments.

Paralititan’s skull shows unique adaptations for its shellfish diet, including reinforced jaw muscles and specially shaped teeth that could crack open even the toughest shells. The dinosaur’s long neck allowed it to reach deep into underwater crevices where shellfish liked to hide, while its massive size meant it could wade into deeper waters than smaller dinosaurs.

The calcium-rich diet provided by constant shellfish consumption helped Paralititan grow to enormous sizes, reaching lengths of over 80 feet. This specialized feeding strategy was so successful that it supported some of the largest land animals that ever lived on Earth.

Insect-Hunting Epidexipteryx: The Tiny Termite Specialist

Not all dinosaurs were giants – some were perfectly content living in the miniature world of insects and grubs. Epidexipteryx, a sparrow-sized dinosaur from ancient China, specialized in hunting insects hiding in tree bark and rotting logs, much like modern woodpeckers do today.

This tiny predator possessed incredibly long, thin fingers that could probe deep into crevices and extract insects with surgical precision. Its teeth were small and sharp, perfect for crunching through chitinous exoskeletons. Epidexipteryx likely spent its days methodically searching dead trees for beetle larvae, termites, and other protein-rich insects.

The discovery of Epidexipteryx’s insect-hunting lifestyle revealed that dinosaurs occupied ecological niches at every level of the food chain. While their giant relatives dominated the landscape, these tiny specialists were busy exploiting resources that larger dinosaurs couldn’t access.

Salt-Licking Nigersaurus: The Mineral Miner

In the harsh, arid landscapes of Cretaceous Africa, Nigersaurus developed one of the most unusual feeding strategies in dinosaur history. This duck-billed dinosaur didn’t just eat plants – it actively sought out mineral-rich salt deposits and incorporated them into its daily diet for essential nutrients.

Nigersaurus possessed a unique mouth structure with hundreds of tiny teeth arranged in dental batteries, perfect for scraping salt and mineral crusts from rock surfaces. The dinosaur’s wide, flat mouth could cover large areas of mineral deposits, allowing it to harvest essential elements like sodium, calcium, and magnesium that were scarce in the desert environment.

This mineral-mining behavior was crucial for Nigersaurus’s survival in one of Earth’s most challenging environments. The salt and minerals helped maintain proper bodily functions and supported the dinosaur’s rapid growth, proving that even in ancient times, animals understood the importance of dietary supplements.

Fungus-Farming Amargasaurus: The Prehistoric Mushroom Cultivator

Long before humans discovered agriculture, Amargasaurus was already practicing a form of farming that would make modern mycologists jealous. This long-necked dinosaur actively cultivated and harvested fungi from rotting logs and decomposing plant matter, creating its own sustainable food source.

Amargasaurus possessed specialized gut bacteria that could break down complex fungal compounds, allowing it to digest mushrooms and other fungi that would be toxic to most other dinosaurs. The dinosaur’s behavior patterns suggest it would return to the same rotting logs repeatedly, managing its fungal farms like a prehistoric gardener.

This fungus-farming strategy provided Amargasaurus with a reliable food source that was available year-round, regardless of seasonal changes in plant growth. The high protein content of fungi also helped support the dinosaur’s massive size and energy requirements.

Nectar-Sipping Kulindadromeus: The Hummingbird Dinosaur

Picture a dinosaur hovering delicately over prehistoric flowers, its long tongue darting out to collect sweet nectar – this was the daily routine of Kulindadromeus, one of the most specialized feeders in dinosaur history. This small, bird-like dinosaur had evolved a feeding strategy remarkably similar to modern hummingbirds.

Kulindadromeus possessed an extremely long, thin tongue that could reach deep into flower corollas to access nectar. Its lightweight build and powerful flight muscles allowed it to hover in place while feeding, just like modern nectar-feeding birds. The dinosaur’s diet was so specialized that it likely co-evolved with specific flowering plants that depended on it for pollination.

The discovery of Kulindadromeus’s nectar-feeding lifestyle revealed that dinosaurs had evolved complex plant-animal relationships millions of years before mammals took over these ecological roles. This tiny dinosaur was essentially a prehistoric pollinator, playing a crucial role in the evolution of flowering plants.

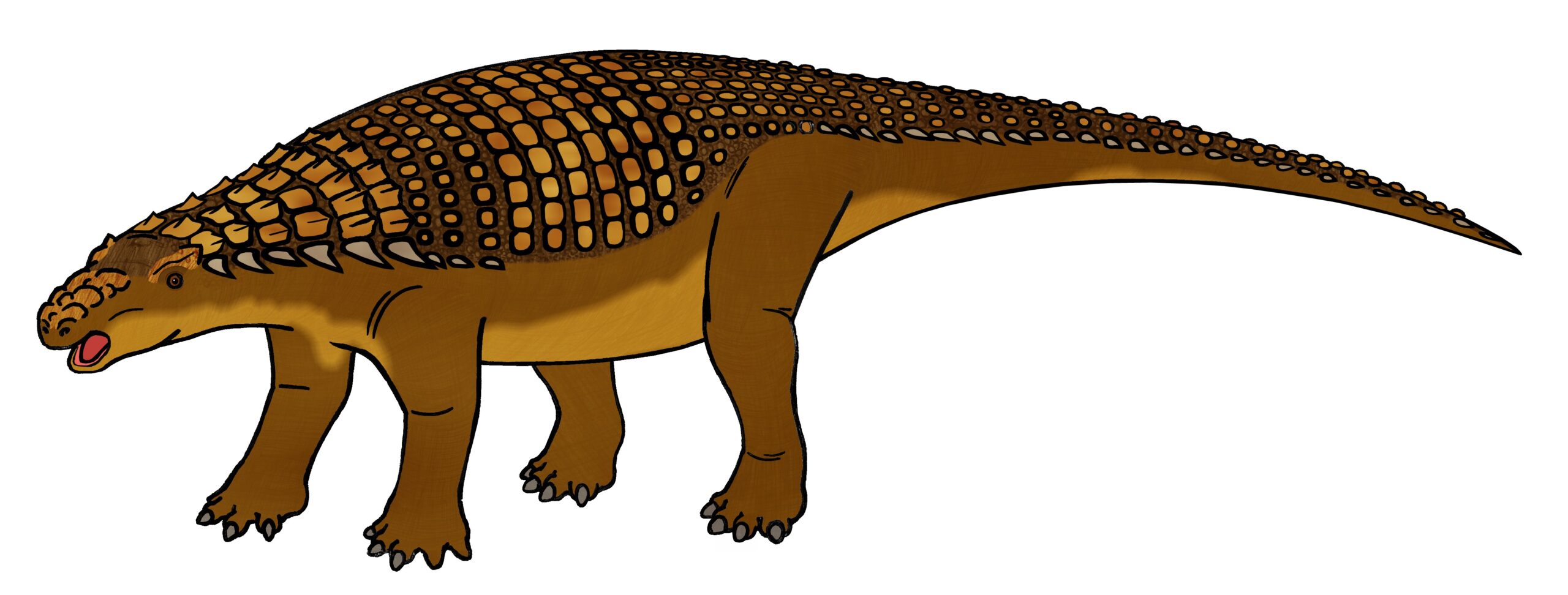

Mud-Filtering Borealopelta: The Prehistoric Filter Feeder

In the shallow seas and estuaries of ancient Canada, Borealopelta developed a feeding strategy that was more commonly associated with whales than dinosaurs. This heavily armored ankylosaur specialized in filter-feeding, straining tiny organisms and organic particles from muddy water.

Borealopelta’s mouth was equipped with specially modified teeth that worked like a primitive baleen system, allowing it to take in large amounts of water and sediment before filtering out the edible particles. The dinosaur’s massive gut could process enormous quantities of low-quality food, extracting nutrients from microscopic plankton, algae, and organic debris.

This filter-feeding lifestyle allowed Borealopelta to exploit a food source that was largely untapped by other dinosaurs. The strategy was so successful that it supported the evolution of some of the most heavily armored dinosaurs ever discovered, with their thick bony plates serving as protection while they fed in vulnerable positions.

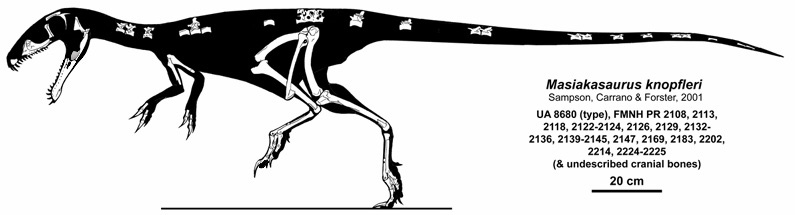

Carrion-Specialized Masiakasaurus: The Vulture Dinosaur

In the ecosystem of ancient Madagascar, Masiakasaurus filled a crucial but unglamorous role as nature’s cleanup crew. This medium-sized theropod dinosaur specialized in feeding on carrion, developing unique adaptations that made it perfectly suited for a scavenging lifestyle.

Masiakasaurus possessed forward-projecting teeth that were ideal for stripping meat from bones and accessing difficult-to-reach areas of carcasses. Its powerful digestive system could handle partially decomposed meat that would sicken other predators, while its excellent sense of smell helped it locate carrion from miles away.

The dinosaur’s scavenging behavior was so efficient that it could clean a large carcass down to the bones within days, preventing the spread of disease and recycling nutrients back into the ecosystem. Masiakasaurus essentially functioned as a prehistoric vulture, playing a vital role in maintaining ecological balance.

Conclusion: A Prehistoric Buffet Beyond Imagination

The diverse and often bizarre feeding strategies of dinosaurs reveal a lost world far more complex and fascinating than any Hollywood blockbuster could capture. From stone-swallowing giants to blood-sucking miniatures, these ancient creatures evolved incredible solutions to the eternal challenge of finding food in a competitive world.

Each weird diet tells a story of adaptation, survival, and ecological innovation that shaped the course of life on Earth. These dinosaurs didn’t just eat to survive – they pioneered feeding strategies that would later be adopted by mammals, birds, and other creatures that inherited their world.

The next time you watch a nature documentary or visit a museum, remember that the strangest feeding behaviors you see today are just echoes of innovations that dinosaurs perfected millions of years ago. What other secrets about prehistoric dining are still waiting to be discovered in the fossil record?