In the vast panorama of prehistoric life, few dinosaurs command attention quite like Torosaurus, the bearer of the longest skull ever recorded among land vertebrates. This magnificent ceratopsian, whose name means “perforated lizard,” roamed the landscapes of western North America during the late Cretaceous period, approximately 68-66 million years ago. With its massive frilled skull stretching up to 2.8 meters (9.2 feet) in length, Torosaurus represents one of the most impressive cranial developments in evolutionary history. While often overshadowed by its famous relative, the Triceratops, in popular culture, the Torosaurus has become increasingly significant to paleontologists seeking to understand the diversity and evolution of horned dinosaurs. This remarkable creature’s anatomy, behavior, and place in prehistoric ecosystems continue to fascinate scientists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike.

Discovery and Naming: Unveiling the “Perforated Lizard”

Torosaurus was first described by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1891, based on specimens discovered in Wyoming’s Lance Formation. The genus name combines the Greek words “toros” (perforated) and “sauros” (lizard), referring to the distinctive large openings or “fenestrae” in its expansive neck frill. Initially, only fragmentary material was known, primarily portions of the distinctive frill. Unlike many dinosaur discoveries that generate immediate public fascination, Torosaurus remained relatively obscure for decades, overshadowed by more completely known ceratopsians. The first substantial specimens were collected during the “Bone Wars” period of competitive fossil hunting in the American West, a time when Marsh was in fierce competition with Edward Drinker Cope. Additional specimens discovered throughout the 20th and 21st centuries have gradually provided a more complete picture of this impressive dinosaur, though complete skeletons remain relatively rare compared to some other ceratopsian species.

Record-Breaking Skull Dimensions

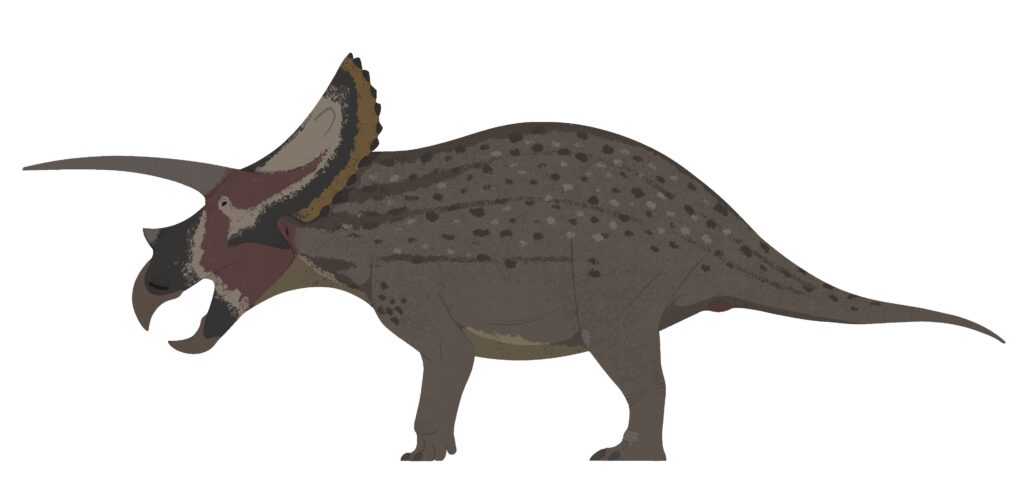

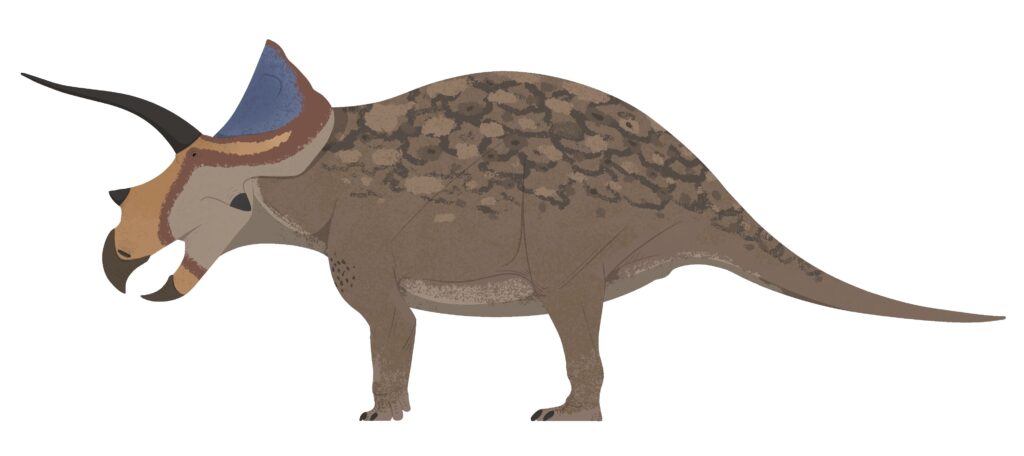

Torosaurus lays claim to the longest skull of any known land vertebrate, with the largest specimens measuring approximately 2.8 meters (9.2 feet) from the tip of the snout to the edge of the frill. This extraordinary structure comprises nearly one-third of the animal’s entire body length, creating a truly distinctive profile unlike any modern animal. The skull’s size is primarily due to its enormous, thin bony frill that extends backward from the base of the skull, forming a shield-like structure. While the basic skull architecture resembles that of its relative Triceratops, Torosaurus is distinguished by having a significantly longer and wider frill with characteristic large openings or “fenestrae.” For comparison, even the largest elephant skulls measure less than one meter in length, underscoring just how exceptional the Torosaurus skull truly is. The evolutionary advantages of such an enormous cranial structure have been debated extensively, with theories ranging from visual display to thermoregulation.

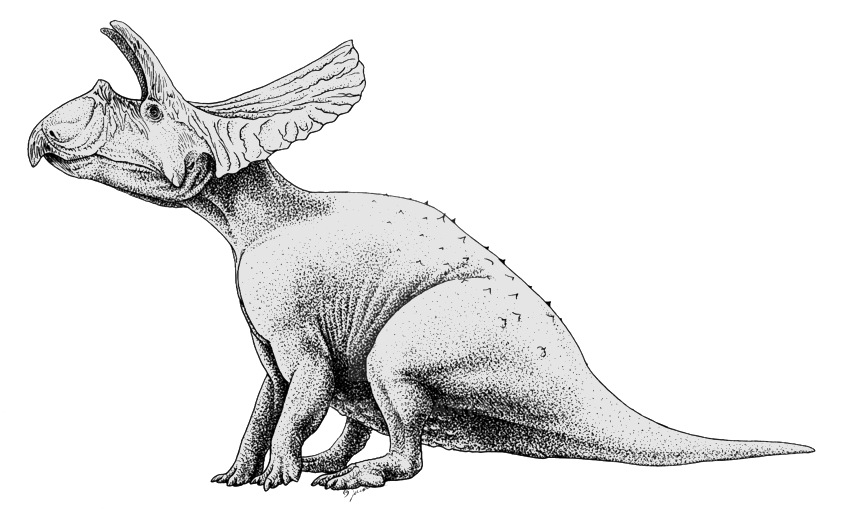

Distinctive Anatomical Features

Beyond its record-breaking skull, Torosaurus possessed numerous distinctive anatomical features that set it apart from other ceratopsians. Like Triceratops, it sported three facial horns—a short nose horn and two longer brow horns that could reach over 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length, projecting forward from above the eyes. These substantial horns likely served both defensive and display purposes within the species. Its massive frill featured a scalloped edge with small epoccipitals (bone protrusions) and the characteristic large fenestrae or openings that give the dinosaur its name. Torosaurus walked on four sturdy, column-like limbs, with the front legs somewhat shorter than the hind legs, giving the body a slight downward slope toward the head. Adult Torosaurus reached approximately 7.6 to 9 meters (25 to 30 feet) in length and weighed an estimated 6-8 metric tons, making it one of the larger ceratopsians. The rest of its body plan followed the typical ceratopsian blueprint: a barrel-shaped torso, powerful limbs, and a relatively short tail compared to many other dinosaur groups.

The Triceratops Controversy: One Dinosaur or Two?

One of the most intriguing and contentious debates in paleontology concerns the relationship between Torosaurus and Triceratops. In 2010, paleontologists John Scannella and Jack Horner proposed that Torosaurus was not a separate genus but rather represented the fully mature form of Triceratops. According to this hypothesis, as Triceratops aged, its solid frill would thin out and develop the characteristic holes seen in Torosaurus specimens. This dramatic morphological change would represent an extreme example of ontogeny (growth-related changes) in dinosaurs. The controversy sparked intense discussion within the scientific community, with numerous subsequent studies examining bone histology, statistical analyses of specimens, and comparative anatomy to test the hypothesis. Several researchers have since published evidence challenging this “single dinosaur” theory, noting differences in horn orientation, frill shape, and other features that appear inconsistent with simple maturation processes. The debate remains ongoing, with most current evidence suggesting they were likely separate genera, though closely related.

Habitat and Geographic Range

Torosaurus inhabited western North America during the latest Cretaceous period, specifically in what is now the western United States and southern Canada. Fossils have been discovered primarily in formations dating to the Maastrichtian age (72-66 million years ago), including the Lance Formation in Wyoming, the Hell Creek Formation spanning Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota, and the Frenchman Formation in Saskatchewan. During this time, the Western Interior Seaway that once divided North America was retreating, creating vast coastal plains and river deltas that provided rich vegetation for herbivorous dinosaurs. The environment Torosaurus inhabited was a warm, subtropical climate with seasonal rainfall, supporting diverse plant communities dominated by angiosperms (flowering plants), conifers, ferns, and cycads. This lush ecosystem supported numerous other dinosaur species alongside Torosaurus, including other ceratopsians, hadrosaurs, ankylosaurs, and the apex predator Tyrannosaurus rex. The distribution of Torosaurus fossils suggests it may have preferred slightly different habitats or geographic ranges than Triceratops, despite their overlapping territories.

Diet and Feeding Adaptations

As a member of the ceratopsid family, Torosaurus was an herbivore with specialized adaptations for processing tough plant material. Its powerful beak-like structure at the front of the jaw could snip vegetation, while batteries of tightly packed teeth formed effective grinding surfaces for breaking down fibrous plant matter. Unlike some other dinosaur groups that swallowed food whole, ceratopsians like Torosaurus chewed their food thoroughly before swallowing. Microscopic wear patterns on ceratopsian teeth suggest they primarily fed on tough, fibrous vegetation that required significant processing. The exact plant species iTorosaurus’s diet remains speculative, but likely included cycads, palms, ferns, and early flowering plants that were becoming increasingly common in the late Cretaceous. Some paleontologists have suggested that the long frill might have provided attachment points for exceptionally powerful jaw muscles, potentially allowing Torosaurus to process even tougher vegetation than other ceratopsians. Its height and reach would have permitted it to browse on low to medium vegetation, possibly giving it access to different food resources than shorter ceratopsians.

The Purpose of the Massive Frill

The enormous frill of Torosaurus represents one of the most striking structures in dinosaur anatomy, and scientists have proposed multiple theories regarding its function. The traditional view suggested a defensive purpose, with the frill serving as a shield against predators like Tyrannosaurus rex. However, the presence of large fenestrae (holes) in the frill would have compromised its effectiveness as protective armor, leading researchers to question this hypothesis. More recent interpretations emphasize display functions, with the frill potentially serving as a visual signal to intimidate rivals or attract mates, similar to the elaborate headgear of modern deer or birds. The expansive surface area may have also played a role in thermoregulation, helping to dissipate excess body heat through the presumably vascularized frill tissue. Muscle attachment evidence suggests the frill supported significant musculature, particularly around the jaw, potentially enhancing the animal’s powerful bite force for processing vegetation. Some researchers propose that different ceratopsian frill designs represented species-recognition features, helping these animals identify potential mates from the same species in environments where multiple horned dinosaurs coexisted.

Social Behavior and Herd Dynamics

While direct evidence of Torosaurus social behavior is limited, paleontologists have made inferences based on related ceratopsians and the nature of their fossil discoveries. Several ceratopsian species are known from bonebeds containing multiple individuals, suggesting these animals may have lived in herds for at least part of their lives. Though no definitive Torosaurus bonebeds have been discovered, the advantages of herd living—including protection from predators and efficient foraging—would likely have benefited these large herbivores. The elaborate frills and horns may have played crucial roles in establishing dominance hierarchies within herds, with larger, more impressive displays potentially signaling higher social status. Fossil evidence from related ceratopsians shows varying degrees of horn and frill damage, suggesting possible intraspecific combat similar to modern horned mammals. The potential for sexual dimorphism—differences between males and females—has been suggested but remains difficult to establish definitively due to the limited number of specimens and ongoing taxonomic debates. If Torosaurus followed patterns seen in other large herbivorous dinosaurs, they may have formed complex social groups with age and sex segregation.

Growth and Development

Understanding the growth patterns of Torosaurus has been complicated by the limited number of specimens and the ongoing debate about its relationship to Triceratops. If Torosaurus represents a separate genus, researchers must work with relatively few specimens representing different growth stages. Bone histology studies suggest that, like other large dinosaurs, Torosaurus experienced rapid growth during its early years before reaching a period of slower growth as it approached adulthood. The distinctive frill appears to have developed gradually, potentially expanding and developing its characteristic fenestrae as the animal matured. Some studies suggest that full maturity in large ceratopsids might not have been reached until 15-20 years of age, though growth rates could vary based on environmental conditions and food availability. The substantial size difference between juvenile and adult specimens indicates dramatic changes throughout development, with adults potentially weighing ten times more than younger individuals. If the controversial hypothesis that Torosaurus represents mature Triceratops is correct, this would represent one of the most dramatic ontogenetic transformations known in dinosaurs, involving substantial remodeling of the skull in late adulthood.

Predators and Defense Mechanisms

During the late Maastrichtian age when Torosaurus lived, the dominant predator across western North America was Tyrannosaurus rex, which undoubtedly posed a significant threat to even large ceratopsians. Fossil evidence, including Triceratops bones bearing healed T. rex tooth marks, confirms that tyrannosaurids actively hunted horned dinosaurs. Torosaurus’ impressive arsenal of defensive features included its three substantial horns, which could potentially inflict serious damage on attacking predators. The massive size of adult specimens, weighing 6-8 tons, would have made them challenging prey, likely requiring coordinated attacks from predators or the targeting of vulnerable individuals. When threatened, Torosaurus could have adopted a defensive stance, lowering its head to present its formidable horns toward predators, similar to how modern rhinoceros use their horns. Herd living, if practiced by Torosaurus, would have provided additional protection through increased vigilance and the possibility of coordinated defense against predators. Young Torosaurus, lacking the full development of adult defensive features, would have been particularly vulnerable, possibly explaining why juvenile specimens are rarely found.

Extinction: The End of the Horned Giants

Torosaurus existed during the final stages of the Cretaceous period, vanishing in the mass extinction event that occurred approximately 66 million years ago at the Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) boundary. This catastrophic extinction, widely attributed to the impact of a massive asteroid in what is now the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, eliminated approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. The timing of Torosaurus’ extinction is particularly significant, as fossil evidence suggests the genus survived almost to the very end of the Cretaceous, making it one of the last dinosaur species to exist before the extinction event. Studies of the Hell Creek Formation, where Torosaurus fossils are found in the uppermost layers, indicate that ceratopsian diversity remained relatively high right up until the K-Pg boundary, contradicting earlier hypotheses that dinosaurs were already in decline before the asteroid impact. The extinction of specialized herbivores like Torosaurus would have had cascading effects throughout the ecosystem, creating ecological vacancies that would eventually be filled by mammals during the subsequent Paleogene period.

Research Challenges and Future Directions

Studying Torosaurus presents numerous challenges for paleontologists, beginning with the relative scarcity of specimens compared to other ceratopsians like Triceratops. Complete or nearly complete skulls are exceptionally rare, with only a handful known to science, and articulated post-cranial skeletons are even more elusive. The ongoing taxonomic debate regarding its relationship with Triceratops complicates research efforts, as scientists must carefully consider whether apparent differences represent distinct species or growth variations within a single taxon. Future discoveries, particularly of growth series showing developmental changes, would significantly advance our understanding of Torosaurus. Advanced technological approaches, including CT scanning of fossils, finite element analysis to test biomechanical hypotheses, and improved histological techniques, offer promising avenues for future research. Paleontologists continue searching for Torosaurus specimens in late Cretaceous formations across western North America, hoping to find more complete specimens that might help resolve ongoing questions. Stable isotope analyses of tooth enamel could provide insights into diet and habitat preferences, potentially clarifying ecological differences between Torosaurus and other contemporary ceratopsians.

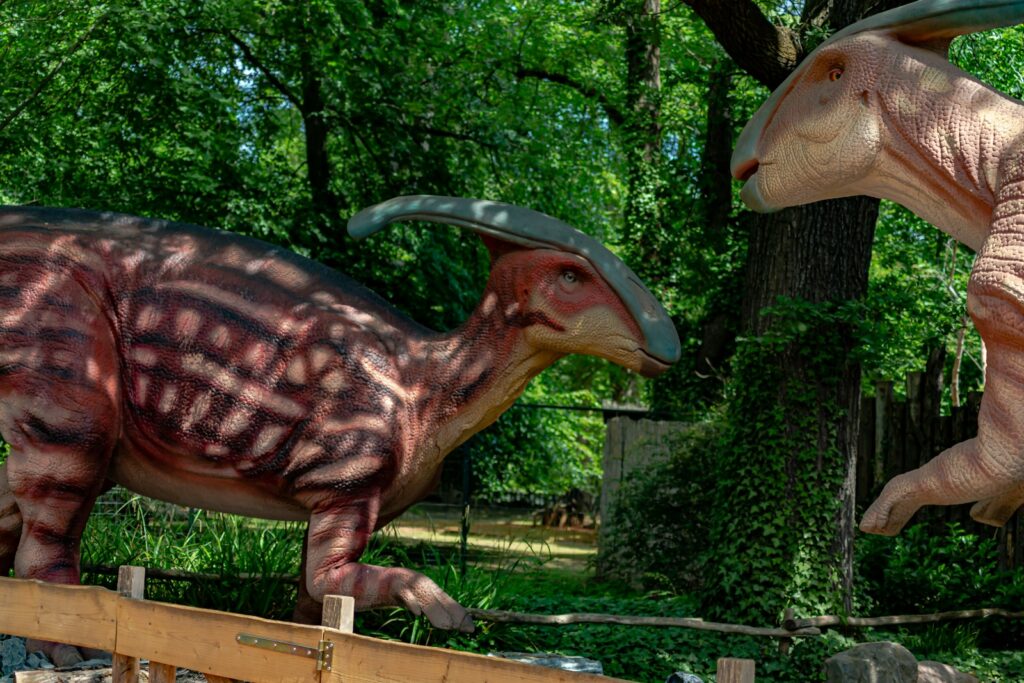

Cultural Impact and Representation

Despite possessing the longest skull of any land vertebrate in Earth’s history, Torosaurus has not achieved the same level of cultural recognition as its relative Triceratops or other famous dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus and Velociraptor. This relative obscurity stems partly from its later discovery and fewer complete specimens, limiting its representation in early museum displays and popular media. When Torosaurus does appear in educational contexts, its massive frill and record-breaking skull dimensions are typically emphasized as its most distinctive features. Several major natural history museums display Torosaurus specimens or reconstructions, including the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, which houses specimens collected by O.C. Marsh during the original description of the genus. The ongoing scientific debate about whether Torosaurus represents a distinct genus or a mature Triceratops has occasionally captured public attention, demonstrating how paleontological controversies can engage broader audiences. In recent years, improved scientific illustrations and museum exhibits have begun to give Torosaurus more visibility, helping to establish its identity as one of the most impressive horned dinosaurs. Digital reconstructions in documentary programs have further helped to bring this massive-skulled dinosaur to life for modern audiences.

Conclusion

The story of Torosaurus represents a fascinating chapter in Earth’s prehistoric narrative. With its record-breaking skull spanning nearly three meters, this ceratopsian pushed the boundaries of vertebrate cranial evolution to extremes never seen before or since. Though questions remain about its taxonomy, ecology, and behavior, ongoing research continues to illuminate the life and times of this remarkable creature. As scientists apply new technologies and analytical approaches to existing specimens and hopefully discover new ones, our understanding of Torosaurus will undoubtedly deepen. Whether viewed as a distinct genus or as the mature form of Triceratops, this dinosaur’s extraordinary skull stands as a testament to the remarkable diversity of life that existed in the shadow of extinction during the final days of the Cretaceous period.