Triceratops, with its distinctive three-horned face and massive frilled shield, stands as one of the most recognizable dinosaurs ever to roam the Earth. This remarkable herbivore lived during the final stages of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 68 to 66 million years ago, making it a contemporary of the fearsome Tyrannosaurus rex. As one of the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist before the Cretaceous-Paleogene extinction event, Triceratops has captured our collective imagination since its discovery in the late 19th century. Its imposing appearance, fascinating biology, and rich fossil record have made it a cornerstone of paleontological research and popular culture alike.

Discovery and Naming

The first Triceratops specimens were discovered in 1887 by George Lyman Cannon near Denver, Colorado, though initially, only a pair of horns attached to a partial skull was found. These remains were sent to paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh, who first believed they belonged to an unusual bison species from the Ice Age. Upon receiving more complete material, Marsh recognized his error and formally named the genus Triceratops in 1889, derived from Greek words meaning “three-horned face.” The type species, Triceratops horridus, was soon followed by numerous other proposed species as more fossils were uncovered throughout the American West. This initial taxonomic confusion would persist for over a century, with scientists debating how many true Triceratops species actually existed based on variations in fossil morphology.

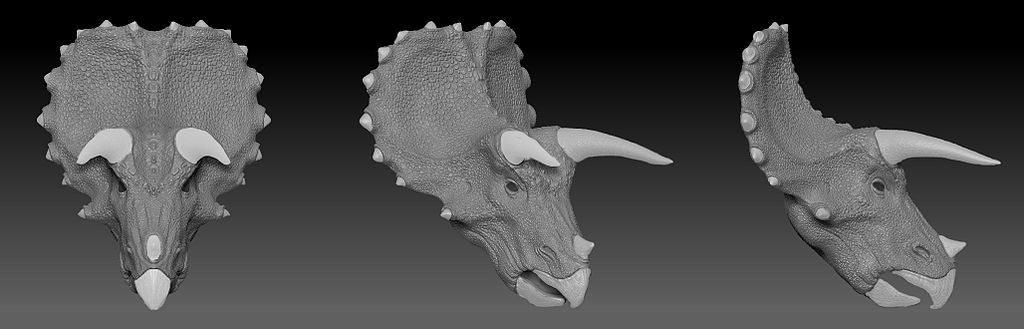

Physical Characteristics

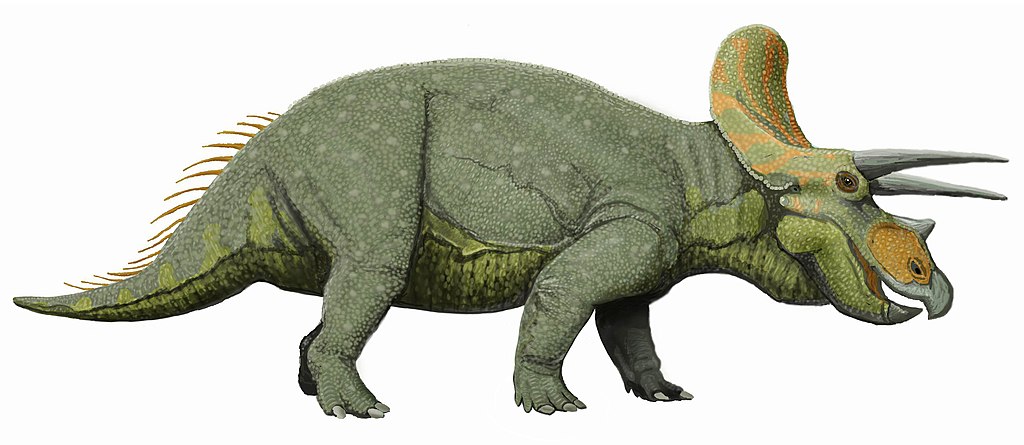

Triceratops was a massive quadrupedal herbivore, typically measuring between 25 and 30 feet in length and weighing up to 12 tons—comparable to a modern elephant. Its most distinctive features included three facial horns: two large, forward-facing horns above the eyes that could reach over 3 feet in length, and a smaller horn positioned on the snout. Behind these impressive weapons extended an enormous solid frill or shield made of bone that projected from the back of the skull, providing protection for the neck region. This frill could span up to 7 feet across, making the Triceratops skull one of the largest of any land animal that ever lived. The dinosaur’s body was robust and tank-like, supported by four sturdy, column-like limbs, with three-toed hooves on the front feet and four-toed hooves on the hind feet.

Evolutionary History

Triceratops belonged to the ceratopsid family, a diverse group of horned, frilled dinosaurs that evolved during the Late Cretaceous Period. More specifically, it was part of the chasmosaurine subfamily, characterized by their elongated frills and prominent brow horns. The evolutionary history of Triceratops shows a fascinating progression from earlier ceratopsians like Protoceratops, which had smaller frills and lacked well-developed horns. Paleontologists have identified possible transitional forms, such as Chasmosaurus and Pentaceratops, demonstrating incremental developments in horn and frill morphology. Triceratops represents one of the most specialized and latest-occurring members of this evolutionary lineage, having evolved its distinctive three-horned arrangement and massive solid frill as the culmination of millions of years of ceratopsid evolution before the lineage was terminated by the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

Habitat and Range

Triceratops inhabited what is now western North America, with fossil remains predominantly found in the western United States and Canada, particularly in formations like the Hell Creek Formation, Lance Formation, and Scollard Formation. During the Late Cretaceous, this region was part of an ancient landmass called Laramidia, formed when a shallow seaway divided North America into eastern and western portions. The environment Triceratops called home was a warm, subtropical coastal floodplain characterized by rivers, swamps, and forested areas that provided abundant vegetation for these large herbivores. Fossil evidence suggests that Triceratops may have preferred woodland habitats rather than open plains, where its size and defensive adaptations would have been most effective against predators like Tyrannosaurus. The distribution of fossils indicates that Triceratops was one of the most common large herbivores in its ecosystem, suggesting it was highly successful in its environmental niche.

Diet and Feeding Habits

As a dedicated herbivore, Triceratops possessed a specialized feeding apparatus perfectly adapted for processing tough plant material. Its distinctive parrot-like beak was formed by a toothless rostral bone at the front of the mouth, enabling it to crop vegetation efficiently. Behind this beak lay batteries of hundreds of teeth arranged in dental columns, with up to five teeth stacked in each column and as many as 40 columns per jaw—creating an impressive grinding surface capable of processing fibrous plant matter. These teeth were continuously replaced throughout the animal’s life as they wore down from constant use. Scientific analyses of Triceratops jaw mechanics suggest it employed a powerful slicing bite rather than simple cropping or grinding actions. Its diet likely consisted of low-growing vegetation including cycads, ferns, palms, and primitive flowering plants that were becoming increasingly common during the Late Cretaceous Period.

Social Behavior

The social behavior of Triceratops remains a subject of ongoing research and debate among paleontologists. While direct evidence of their social structure is limited, certain fossil discoveries provide intriguing clues. Some bone beds containing multiple Triceratops individuals have led some scientists to suggest they may have formed herds, at least during certain periods of their lives, similar to modern elephants or rhinoceroses. The conspicuous nature of their horns and frills has prompted theories about their use in visual display and species recognition, which would be particularly important in social contexts. Variation in horn and frill morphology between individuals might represent sexual dimorphism or age-related differences, potentially indicating complex social hierarchies. The metabolic demands of such large animals would have required substantial feeding territories, which might suggest seasonal migrations or nomadic behavior in response to food availability.

Defense Mechanisms

Triceratops’ most obvious defensive adaptations were its imposing horns and solid bone frill, which served as formidable protection against the apex predators of its time, particularly Tyrannosaurus rex. The two long brow horns, which could grow to over three feet in length, provided effective weapons for goring attackers, while the shorter nasal horn may have added additional offensive capability during confrontations. The massive frill protected the vulnerable neck region and may have made Triceratops appear even larger when facing predators. Compelling evidence for predator-prey interaction comes from Triceratops bones bearing healed bite marks matching Tyrannosaurus teeth, indicating that some individuals survived attacks. Additionally, Tyrannosaurus skeletons have been found with injuries consistent with being gored by large horns, suggesting that Triceratops was capable of successfully defending itself and even inflicting fatal wounds on would-be predators.

Growth and Development

Recent studies examining the microstructure of Triceratops bones have revealed fascinating details about their growth and development. Hatchling Triceratops would have been relatively small, perhaps weighing just a few pounds, with less pronounced horns and frills than adults. Analysis of growth rings in fossil bones indicates that young Triceratops experienced rapid growth during their early years, similar to modern elephants and other large mammals. Scientists estimate that these dinosaurs reached sexual maturity between 7 and 10 years of age, though they continued growing throughout much of their lives at progressively slower rates. The development of their distinctive cranial features—the horns and frill—underwent significant changes as individuals matured, with the brow horns gradually curving forward and the frill expanding and thickening. This ontogenetic transformation was so dramatic that juvenile specimens were occasionally misclassified as different species before paleontologists recognized them as immature Triceratops.

Frill Function Debate

The enormous frill of Triceratops has been the subject of extensive scientific debate regarding its primary function. While defense seems an obvious purpose, paleontologists have proposed several additional or alternative functions. Some suggest the frill served as a display structure for species recognition and mating displays, similar to the elaborate plumage of certain birds. The extensive blood vessel channeling visible in frill fossils indicates it may have been covered with keratin and well-supplied with blood vessels, potentially allowing for temperature regulation through heat dissipation. Others propose the frill provided attachment sites for powerful jaw muscles, enhancing Triceratops’ already formidable bite force for processing tough vegetation. Modern consensus generally favors a multi-purpose explanation, with the frill likely serving several of these functions simultaneously—providing defense, facilitating display behaviors, aiding in thermoregulation, and supporting musculature essential for feeding.

Paleoenvironment and Ecosystem

Triceratops inhabited a rich and diverse ecosystem during the final stages of the Cretaceous Period. Its world was populated by numerous other dinosaur species, including its predator Tyrannosaurus rex, the armored Ankylosaurus, duck-billed hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus, and smaller theropods such as Troodon and Dakotaraptor. Beyond dinosaurs, the environment teemed with primitive mammals, birds, amphibians, and reptiles, while the plant life consisted of a mixture of conifers, ginkgoes, cycads, and early flowering plants. Climate studies of this period indicate the region experienced seasonal variations in a generally warm, humid climate. As one of the largest and most common herbivores in this ecosystem, Triceratops would have played a crucial ecological role, consuming vast amounts of vegetation and likely shaping plant communities through selective feeding. Its abundance in the fossil record suggests it was exceptionally successful within this complex ecosystem, occupying a similar niche to large modern herbivores like rhinoceroses.

Famous Specimens

Several remarkable Triceratops specimens have significantly advanced our understanding of this iconic dinosaur. “Lane,” discovered in North Dakota in 1999, represents one of the most complete Triceratops skeletons ever found, including approximately 75% of the bones and extraordinarily well-preserved skin impressions that revealed details about the dinosaur’s external appearance. Another exceptional specimen is “Kelsey,” a nearly complete Triceratops discovered in Montana in 2006, which preserved rare soft tissue impressions and provided new insights into ceratopsian anatomy. Perhaps the most scientifically significant specimen is known as “Homer,” housed at the Museum of the Rockies, which includes a remarkably well-preserved skull showing evidence of predation by Tyrannosaurus rex, providing direct evidence of interactions between these two famous dinosaurs. The “Dragon King” skeleton, excavated in Wyoming, stands out for its exceptional preservation of the vertebral column and ribcage, offering valuable information about Triceratops’ internal anatomy.

Taxonomic Controversies

The taxonomy of Triceratops has been marked by considerable scientific controversy throughout its study history. Initially, paleontologists named numerous species based on variations in horn length, frill shape, and skull proportions, resulting in up to 16 proposed species by the mid-20th century. However, more recent research has suggested that much of this morphological variation represents individual differences, growth stages, sexual dimorphism, or preservation biases rather than distinct species. A particularly notable controversy emerged in 2009 when researchers proposed that Torosaurus—long considered a separate genus with a longer, fenestrated frill—actually represented mature specimens of Triceratops, implying the two were growth stages of the same animal. This hypothesis, known as taxonomic synonymy, remains contested, with some studies supporting the traditional view of separate genera based on consistent morphological differences. Currently, most paleontologists recognize two valid Triceratops species: T. horridus and T. prorsus, distinguished primarily by horn orientation and skull proportions.

Cultural Impact

Few prehistoric creatures have captured the public imagination quite like Triceratops, which has maintained an enduring presence in popular culture since its discovery. As one of the “starring dinosaurs” in countless books, films, documentaries, and television programs, Triceratops has achieved iconic status alongside Tyrannosaurus rex and Stegosaurus. Its distinctive three-horned silhouette has become instantly recognizable to children and adults alike, appearing in everything from toys and video games to corporate logos and advertising campaigns. The dinosaur features prominently in major museum exhibitions worldwide, with mounted Triceratops skeletons serving as centerpiece attractions at institutions including the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History and the American Museum of Natural History. Beyond entertainment, Triceratops has contributed significantly to science education, frequently serving as an introduction to concepts like evolution, adaptation, and extinction for generations of students.

Extinction and Legacy

Triceratops existed during the very final stages of the Cretaceous Period, with fossil evidence placing them in the last 2-3 million years before the Cretaceous-Paleogene mass extinction event approximately 66 million years ago. This catastrophic event, likely triggered by an asteroid impact in the Yucatán Peninsula, eliminated approximately 75% of all species on Earth, including all non-avian dinosaurs. Fascinatingly, Triceratops fossils have been found in rock layers extremely close to the K-Pg boundary, suggesting they were thriving right up until the extinction event, with no evidence of population decline beforehand. The legacy of Triceratops extends far beyond its biological significance, as its distinctive appearance has made it one of the most familiar dinosaurs in the public consciousness. Its remarkable adaptations continue to inform our understanding of evolution, while ongoing discoveries of new specimens regularly provide fresh insights into dinosaur biology, behavior, and the prehistoric ecosystems of North America.

Conclusion

Triceratops remains one of paleontology’s most significant and beloved subjects, continuing to yield scientific insights more than 130 years after its discovery. Its remarkable combination of defensive weaponry, massive size, and specialized feeding adaptations made it one of the most successful large herbivores of the Late Cretaceous, allowing it to thrive in ecosystems dominated by fearsome predators like Tyrannosaurus rex. As research techniques advance, each new Triceratops discovery helps refine our understanding of this magnificent animal’s life history, from its growth and development to its social behaviors and ecological roles. While we may never be able to observe a living Triceratops, the rich fossil record it left behind ensures that this three-horned giant will continue to captivate scientists and the public alike, standing as an enduring symbol of Earth’s prehistoric past.