The diet of dinosaurs has long fascinated paleontologists and dinosaur enthusiasts alike. By examining fossil evidence, plant remains, and geological data from various prehistoric habitats, scientists have developed increasingly accurate pictures of dinosaur diets. Understanding what dinosaurs ate requires a deep dive into paleoecology—the study of prehistoric ecosystems and how organisms interacted with their environments. Different dinosaur species evolved specialized anatomical features to consume specific types of vegetation available in their habitats, from tough cycads to soft ferns. This relationship between dinosaurs and their food sources provides crucial insights into how these magnificent creatures lived, thrived, and ultimately dominated Earth for over 165 million years.

The Detective Work of Paleobotany

Paleobotany, the study of ancient plant life, serves as a critical tool for understanding dinosaur diets. Scientists meticulously analyze fossilized plant remains found alongside dinosaur fossils to determine what vegetation existed in specific time periods and locations. By identifying plant species present in various geological formations, researchers can reconstruct prehistoric landscapes with remarkable detail. This botanical evidence, combined with analysis of dinosaur dental structures, jaw mechanics, and digestive adaptations, allows paleontologists to make educated determinations about which dinosaurs ate which plants. For example, areas dominated by tall conifers and ginkgoes would support different feeding strategies than regions filled with low-growing ferns and horsetails. These painstaking reconstructions provide the foundation for our understanding of dinosaur dietary habits.

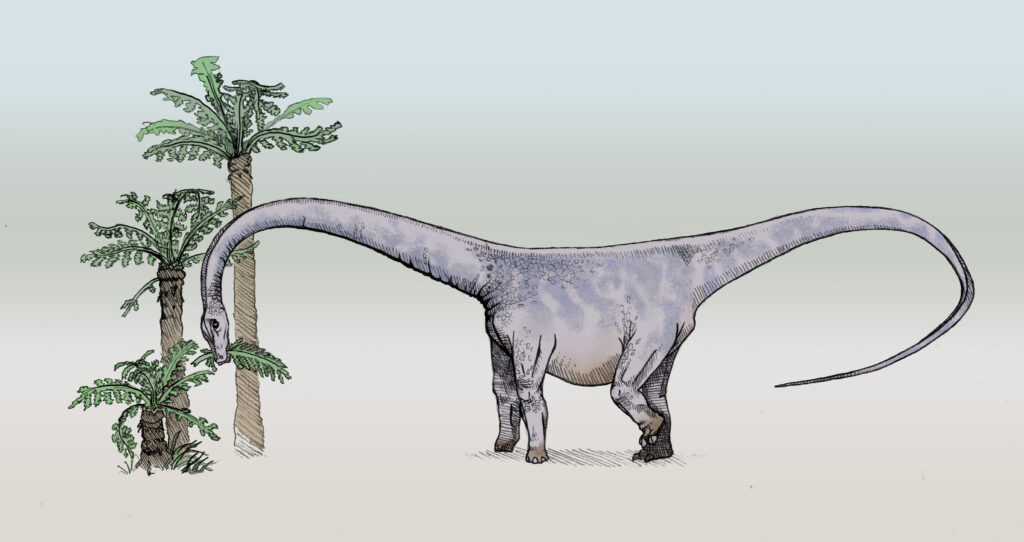

Sauropods: The Giant Forest Browsers

Sauropods, the long-necked giants like Brachiosaurus and Diplodocus, evolved in habitats dominated by tall gymnosperms, including conifers, cycads, and ginkgoes. Their immense height and extraordinarily long necks allowed these behemoths to reach vegetation that was inaccessible to other herbivores, creating a specialized feeding niche. Fossil evidence suggests sauropods consumed massive quantities of tough, nutrient-poor conifer branches and leaves daily to sustain their enormous bodies. Their simple peg-like teeth were adapted for stripping leaves rather than chewing, and they likely used gastroliths (stomach stones) to grind plant material in their digestive tracts. Studies of coprolites (fossilized feces) from sauropods have revealed fragments of conifer needles, cycad fronds, and other woody plant materials, confirming these dietary preferences. This specialized feeding strategy allowed sauropods to become the largest land animals that ever lived, with some species reaching lengths of over 100 feet.

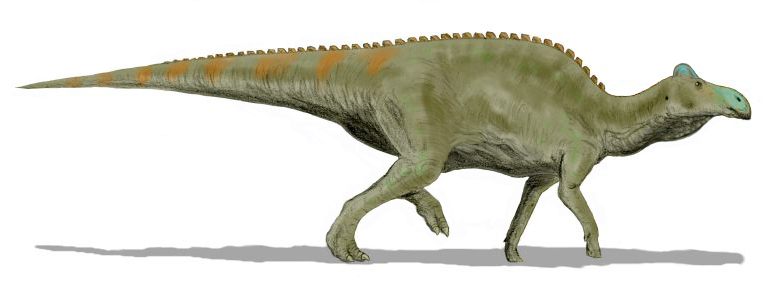

Hadrosaurs: The Chewing Champions

Hadrosaurs, often called “duck-billed dinosaurs,” inhabited diverse environments from coastal plains to upland forests during the Late Cretaceous period. These remarkable herbivores possessed the most sophisticated dental batteries among dinosaurs, featuring hundreds of interlocking teeth that formed efficient grinding surfaces for processing plant material. Unlike sauropods, hadrosaurs thoroughly chewed their food, allowing them to extract more nutrients from tougher vegetation including cycads, conifers, and early flowering plants that were becoming increasingly common during their era. Fossil evidence from preserved stomach contents has revealed that hadrosaurs like Edmontosaurus consumed large quantities of pine needles, twigs, and seeds. Their unique cranial crests may have also played a role in foraging, possibly allowing different species to specialize in distinct plant resources within the same habitat. This dietary flexibility likely contributed to hadrosaurs becoming one of the most successful and diverse dinosaur groups of the Late Cretaceous.

Ceratopsians: The Cycad Specialists

Ceratopsians, the horned dinosaurs like Triceratops and Styracosaurus, evolved in habitats rich with fibrous, low-growing plants such as cycads and early flowering plants. Their powerful beaked mouths functioned similar to modern parrots, capable of slicing through tough plant materials with incredible force. Behind their beaks, ceratopsians possessed dense batteries of shearing teeth arranged in vertical columns that efficiently processed fibrous plant material. Fossil evidence suggests they specialized in consuming cycads—tough, palm-like plants with thick, woody trunks and stiff, spiny leaves that contained toxins deterring many other herbivores. Ceratopsians’ digestive systems likely evolved specialized adaptations to detoxify these chemical compounds, similar to how modern pandas process toxins in bamboo. Their famous neck frills and horns may have evolved primarily for mating displays and species recognition, but they also potentially provided protection while the animals fed with their heads lowered to the ground in vulnerable positions.

Stegosaurs and Ankylosaurs: Low-browsing Specialists

Stegosaurs and ankylosaurs, the armored dinosaurs, were specialized low-browsers that fed on ferns, horsetails, and low-growing cycads abundant in their Jurassic and Cretaceous habitats. Their small heads and weak, simple teeth indicate they performed minimal chewing, instead relying on extensive gut fermentation to break down tough plant fibers. Stegosaurs like Stegosaurus had narrow snouts suggesting selective feeding on particular plants or plant parts, while ankylosaurs had broader muzzles adapted for less discriminate consumption of low vegetation. Studies of preserved gut contents from exceptionally preserved specimens have revealed fern fronds, horsetail stems, and seed fern fragments, confirming these dietary preferences. Both groups evolved powerful but short hind limbs and relatively small forelimbs that kept their bodies close to the ground, ideal for their feeding strategy. Their low-browsing niche allowed these armored dinosaurs to access food sources that were untouched by the high-browsing sauropods, reducing direct competition for resources.

Pachycephalosaurs: The Forgotten Herbivores

Pachycephalosaurs, famous for their thick, domed skulls, were small to medium-sized herbivores that inhabited diverse habitats during the Late Cretaceous. Their dentition provides significant clues about their diet, featuring leaf-shaped cheek teeth ideal for processing fibrous plant material, combined with pointed front teeth suited for selective plucking of fruits, seeds, and soft plant tissues. This combination suggests they were likely opportunistic browsers that consumed a variety of plant foods, possibly including early flowering plants, fruits, seeds, and soft ferns abundant in their environments. The wear patterns on fossilized pachycephalosaur teeth indicate regular consumption of abrasive plant materials. Their relatively small size compared to other herbivorous dinosaurs suggests they may have exploited ecological niches unavailable to larger herbivores, perhaps feeding on undergrowth in forested areas or exploiting seasonal food sources like fruits and seeds. Though often overshadowed by their more famous relatives, pachycephalosaurs represent an important component of Late Cretaceous plant-eating dinosaur communities.

Therizinosaurs: The Bizarre Plant-Eaters

Therizinosaurs represent one of the most unusual evolutionary stories among dinosaurs—carnivorous theropods that transitioned to herbivory. These bizarre dinosaurs possessed enormous, scythe-like claws that likely evolved for pulling branches toward their mouths rather than hunting prey. Their small, leaf-shaped teeth resembled those of other herbivorous dinosaurs, perfectly suited for processing plant material. Therizinosaurs inhabited forested environments in Asia and North America during the Cretaceous period, where they likely consumed a mixed diet of leaves, fruits, and seeds from both gymnosperms and the increasingly abundant flowering plants. Their unusual body shape, with wide hips and a large gut capacity, suggests adaptation for processing large volumes of plant material through fermentation. Analysis of the environments where therizinosaur fossils have been discovered indicates they inhabited lush, forested regions with diverse plant life. This remarkable evolutionary shift from meat-eating to plant-eating represents one of the most dramatic dietary transitions documented in the dinosaur fossil record.

Ornithomimids: The Omnivorous Opportunists

Ornithomimids, often called “ostrich dinosaurs” due to their superficial resemblance to modern ratites, possessed toothless beaks that have puzzled paleontologists trying to determine their diet. Unlike clearly herbivorous or carnivorous dinosaurs, ornithomimids likely occupied an omnivorous niche, consuming both plant materials and small animals. Their habitats spanned diverse environments from woodlands to coastal plains during the Late Cretaceous period. The discovery of gastroliths (stomach stones) in some ornithomimid specimens suggests they consumed plant material that required mechanical breakdown. Their slender, flexible fingers were well-suited for manipulating food items, potentially allowing them to selectively pluck berries, seeds, leaves, and insects from varied vegetation. Examination of ornithomimid skull morphology indicates they had powerful biting force at the tip of their beaks, useful for both cropping plants and capturing small prey. This dietary flexibility would have been advantageous in seasonal environments where available food sources changed throughout the year.

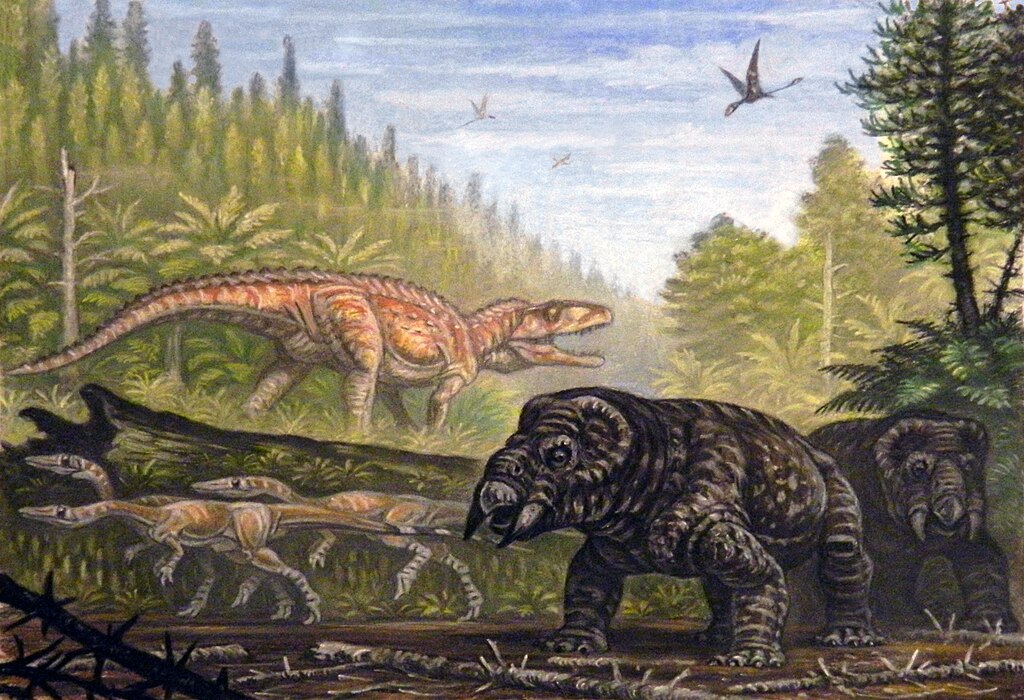

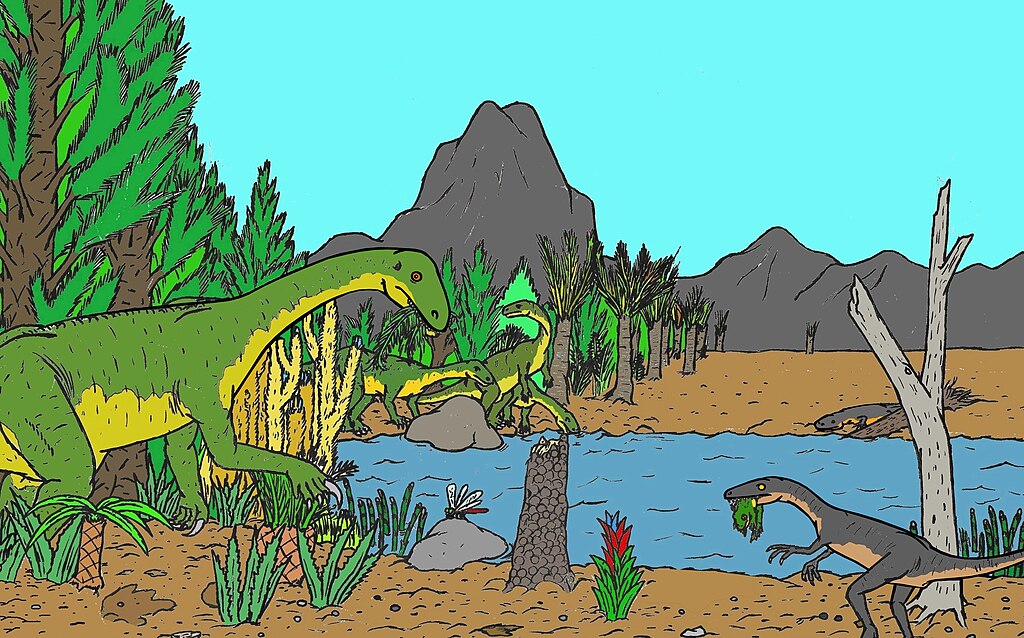

Prosauropods: The Early Plant Pioneers

Prosauropods, the early relatives of sauropods that lived during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic periods, were among the first large-bodied herbivorous dinosaurs. These pioneering plant-eaters inhabited environments dominated by seed ferns, cycads, ginkgoes, and conifers that were becoming established in the aftermath of the Permian-Triassic extinction event. Unlike their later sauropod relatives, prosauropods like Plateosaurus possessed leaf-shaped teeth with serrated edges suitable for slicing through moderately tough plant material. Their semi-bipedal posture allowed them to reach vegetation at various heights, from ground level to several meters up. The fossilized stomach contents of exceptionally preserved prosauropod specimens have revealed a diet consisting primarily of seed fern fronds, conifer branches, and cycad leaves. Their moderately long necks and grasping hands with a semi-opposable thumb enabled selective feeding on nutritious plant parts. As the earliest large herbivorous dinosaurs, prosauropods played a crucial role in shaping plant communities through selective feeding pressure, influencing the evolution of both plants and subsequent herbivorous dinosaurs.

Oviraptorids: The Specialized Seed Crackers

Oviraptorids, despite their name meaning “egg thieves,” were likely specialized plant-eaters with powerful, toothless beaks adapted for processing tough plant materials. These unusual theropods inhabited arid to semi-arid environments in what is now Mongolia and China during the Late Cretaceous period. Their habitats featured diverse vegetation including early flowering plants, conifers, ginkgoes, and cycads. Oviraptorid skulls show remarkable adaptations for powerful biting, with deep, short jaws that could exert considerable force. This morphology suggests they specialized in cracking seeds, nuts, and hard fruits that were becoming increasingly common with the radiation of flowering plants during the Cretaceous. Some researchers have proposed they may have fed on mollusks or other hard-shelled organisms, but the consensus has shifted toward a primarily herbivorous diet. The discovery of gastroliths (stomach stones) in oviraptorid specimens provides further evidence of plant consumption, as these stones would have helped grind tough plant materials in the digestive tract.

The Impact of Changing Flora on Dinosaur Evolution

The dramatic transformation of global plant communities throughout the Mesozoic Era profoundly influenced dinosaur evolution and dietary specializations. The Early Triassic landscape, dominated by seed ferns, horsetails, and primitive conifers, supported the first herbivorous dinosaurs with relatively simple feeding adaptations. As gymnosperms diversified during the Jurassic period, dinosaurs evolved specialized feeding strategies to exploit different plant resources, leading to the radiation of major herbivorous groups including sauropods, stegosaurs, and early ornithischians. The Cretaceous period witnessed the most significant botanical revolution with the emergence and rapid diversification of flowering plants (angiosperms), which fundamentally altered terrestrial ecosystems. This botanical innovation drove further specialization among herbivorous dinosaurs, particularly among hadrosaurs and ceratopsians that evolved increasingly complex dental batteries to process tougher plant materials. The co-evolutionary relationship between plants and dinosaurs represents one of the most important dynamics shaping Mesozoic ecosystems, with each group influencing the evolutionary trajectory of the other through predator-prey interactions and selective pressures.

Reading the Evidence: Coprolites and Stomach Contents

While skeletal adaptations provide important clues about dinosaur diets, direct evidence comes from preserved stomach contents and coprolites (fossilized feces). These rare but invaluable fossils offer unequivocal glimpses into what specific dinosaurs actually consumed. The stomach contents of a beautifully preserved Edmontosaurus mummy revealed conifer needles, twigs, seeds, and fruits, confirming theories about hadrosaur diets derived from their dental structures. Coprolites attributable to large herbivorous dinosaurs frequently contain fragmented plant remains that can be identified to specific plant groups, providing direct evidence of consumption. Modern analytical techniques including scanning electron microscopy and chemical analysis have revolutionized the study of these fossils, allowing researchers to identify minute plant fragments, phytoliths (microscopic silica structures specific to certain plant groups), and even pollen grains preserved within dinosaur coprolites. The discovery of undigested seeds in some coprolites suggests certain dinosaurs may have played important roles in seed dispersal for prehistoric plants, similar to modern elephants and fruit-eating birds. These direct dietary indicators provide crucial verification for hypotheses developed from anatomical studies.

Modern Analogues: What Living Animals Tell Us About Dinosaur Diets

Modern herbivorous animals provide valuable reference points for understanding dinosaur dietary habits, though direct comparisons must be made cautiously. The feeding behaviors of elephants offer insights into possible sauropod browsing strategies, as both groups evolved long necks and specialized dentition for accessing and processing large volumes of vegetation. Giraffes demonstrate how vertical niche partitioning allows exploitation of food resources at different heights within the same habitat, a pattern likely mirrored in diverse dinosaur communities. Studies of modern iguanas and other herbivorous reptiles provide potential models for understanding digestive adaptations in dinosaurs, particularly regarding gut fermentation processes necessary for breaking down tough plant fibers. The specialized beaks of modern birds, particularly parrots and toucans, offer functional analogues for understanding how ceratopsians and other beaked dinosaurs may have processed various plant materials. Even the gut contents of modern herbivores provide comparative data for interpreting fossilized stomach contents and coprolites from dinosaurs. While recognizing the limitations of such comparisons across millions of years of independent evolution, these modern analogues provide valuable frameworks for reconstructing the feeding ecology of extinct dinosaurs.

Dinosaur Dietary Adaptations to Climate Change

Throughout the Mesozoic Era, Earth experienced significant climate fluctuations that dramatically altered plant communities, forcing dinosaurs to adapt their feeding strategies accordingly. During the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic, when global climates were relatively warm and stable, early herbivorous dinosaurs thrived in environments dominated by predictable plant resources. The Middle to Late Jurassic saw increasing seasonality and the spread of conifer forests, favoring the evolution of high-browsing sauropods and low-browsing stegosaurs that could partition these resources. The Cretaceous period witnessed dramatic climate changes, including warming events, sea level fluctuations, and increasing seasonality that corresponded with the radiation of flowering plants. In response, new dinosaur groups including hadrosaurs and ceratopsians evolved specialized dental batteries capable of processing tougher, more fibrous vegetation. Fossil evidence from high-latitude dinosaur communities in Alaska and Antarctica suggests remarkable dietary adaptations to environments with extreme seasonal variations in light and temperature, including possible seasonal migrations or hibernation strategies. These evolutionary responses to changing plant communities demonstrate the remarkable adaptability of dinosaurs throughout their 165-million-year reign.

Conclusion: The Complex Relationship Between Dinosaurs and Plants

In conclusion, studying dinosaur diets offers far more than a glimpse into ancient menus—it reveals the intricate connections between anatomy, environment, and survival in prehistoric ecosystems. From the low-browsing stegosaurs to the beaked oviraptorids and the towering prosauropods, each species adapted to the unique plant life of its time and place. These dietary adaptations not only fueled the rise of the dinosaurs but also shaped the evolutionary paths they followed. As research continues to uncover new fossils and refine our understanding of ancient habitats, the story of what dinosaurs ate will remain a vital key to unlocking the broader narrative of life on Earth during the Mesozoic Era.