Picture this: a massive Tyrannosaurus rex standing upright like a kangaroo, tail dragging on the ground, sporting what looks suspiciously like rabbit ears. This wasn’t some children’s cartoon from the 1950s – this was serious scientific illustration from the 1800s. During the golden age of paleontology, when dinosaur bones were first being unearthed in massive quantities, artists faced an impossible challenge: how do you bring back to life creatures that had been dead for 65 million years with nothing but scattered bones as your guide?

The Kangaroo Dinosaur Phenomenon

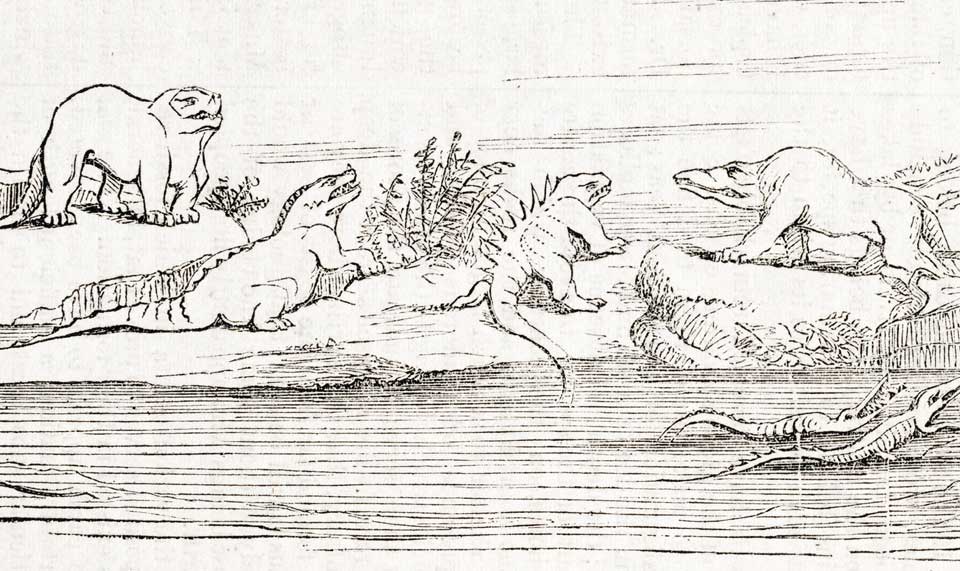

Victorian paleontologists had a peculiar obsession with making dinosaurs look like oversized kangaroos. The famous Crystal Palace dinosaurs in London, unveiled in 1854, show this perfectly – massive creatures sitting upright on their haunches with their tails serving as tripods. Richard Owen, who coined the term “dinosaur,” imagined these beasts as slow, lumbering reptiles that couldn’t possibly support their own weight while standing. The pose made sense to 19th-century minds because it was the only way they could envision such enormous creatures moving around without collapsing. What they didn’t realize was that dinosaurs had hollow bones and sophisticated muscle arrangements that made them far more agile than anyone imagined. These early reconstructions were so influential that the “tripod stance” persisted in popular culture well into the 1960s. Even today, when you see a classic movie monster or vintage toy dinosaur, you’re probably looking at the ghost of Victorian paleontology.

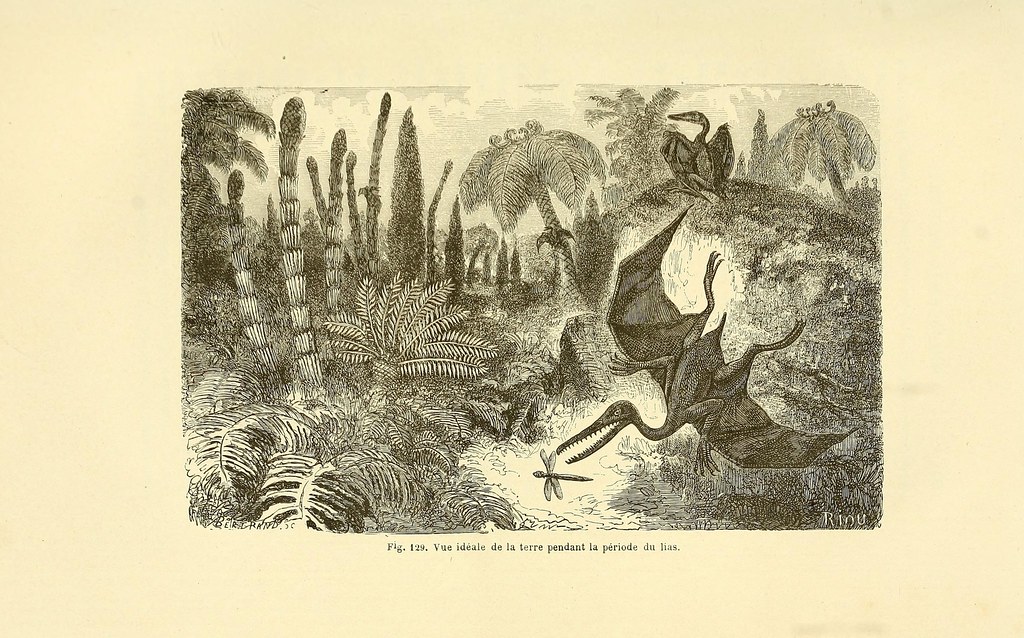

When Science Met Wild Imagination

The line between scientific reconstruction and pure fantasy was incredibly blurry in 19th-century paleontology. Artists would take a single fossilized tooth or vertebra and extrapolate an entire creature, often filling in massive gaps with their own creative interpretations. Charles R. Knight, one of the most famous paleo-artists of the era, once admitted he based his pterosaur wing membranes on bat wings simply because that’s what seemed logical at the time. The result was a menagerie of creatures that looked more like mythological beasts than actual animals. Some illustrations showed dinosaurs with mammalian features like external ears, fur-like textures, and expressions that belonged more on a house cat than a prehistoric predator. The scientific community took these reconstructions seriously because they had so little else to work with – imagination had to fill the void where evidence was lacking.

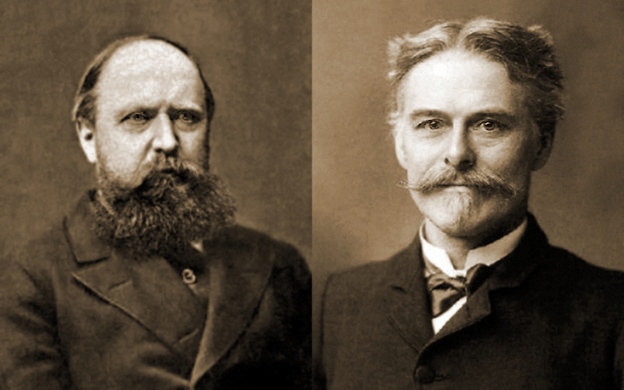

The Great Bone Wars and Artistic Chaos

The infamous rivalry between paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope during the late 1800s didn’t just fuel scientific competition – it created artistic mayhem. Both men rushed to publish their discoveries, often commissioning illustrations before they fully understood what they had found. This led to some spectacular mistakes, like putting the wrong heads on the wrong bodies or creating entirely fictional creatures from mixed-up bone fragments. The pressure to be first meant that accuracy took a backseat to speed and sensationalism. Newspapers of the era loved these “dragon discoveries,” and artists were happy to oblige with increasingly dramatic and fantastical reconstructions. Some illustrations from this period show dinosaurs in impossible poses, defying basic laws of physics and anatomy. The competitive atmosphere meant that wild speculation was often presented as scientific fact, leading the public to believe that dinosaurs were far stranger than they actually were.

Victorian Moral Dinosaurs

Perhaps the most amusing aspect of 19th-century paleo art was how it reflected Victorian social values and moral sensibilities. Artists couldn’t help but project contemporary attitudes onto prehistoric creatures, creating dinosaurs that looked like they belonged in a proper English drawing room. Herbivorous dinosaurs were often depicted as gentle, family-oriented creatures with almost human expressions of kindness and intelligence. Carnivores, on the other hand, were portrayed as moral failures – evil, slovenly beasts with expressions of pure malice. This wasn’t just artistic interpretation; it was Victorian society’s way of making sense of a world where massive predators once ruled the earth. The idea that nature could be “red in tooth and claw” without any moral judgment was difficult for many people to accept. So dinosaurs became characters in a morality play, complete with good guys and bad guys, rather than simply animals trying to survive in their environment.

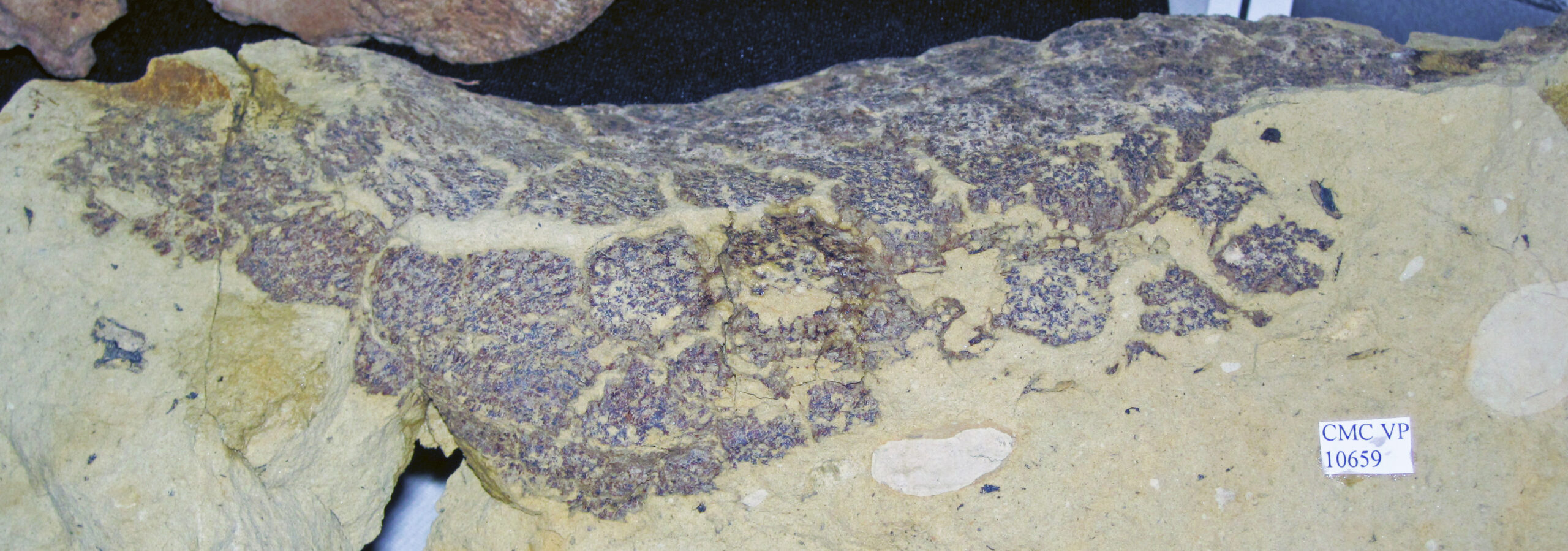

The Mystery of Dinosaur Skin Textures

Without any preserved skin samples to work with, 19th-century artists had to guess what dinosaur hide looked like, and their guesses were wonderfully bizarre. Some illustrations show dinosaurs with smooth, almost rubbery skin like modern elephants, while others feature creatures covered in scales so large they look like medieval armor. A few particularly creative artists gave their dinosaurs fur-like textures or even feathers – though this was purely accidental, as the connection between dinosaurs and birds wasn’t understood yet. The lack of color fossil evidence led to even wilder speculation, with some dinosaurs depicted in garish patterns that would make a peacock jealous. Artists borrowed textures from crocodiles, lizards, elephants, and even fish, creating a patchwork approach to prehistoric skin. Today we know that many dinosaurs actually did have feathers and sophisticated coloration patterns, but the Victorian guesses were usually wrong in the most entertaining ways possible.

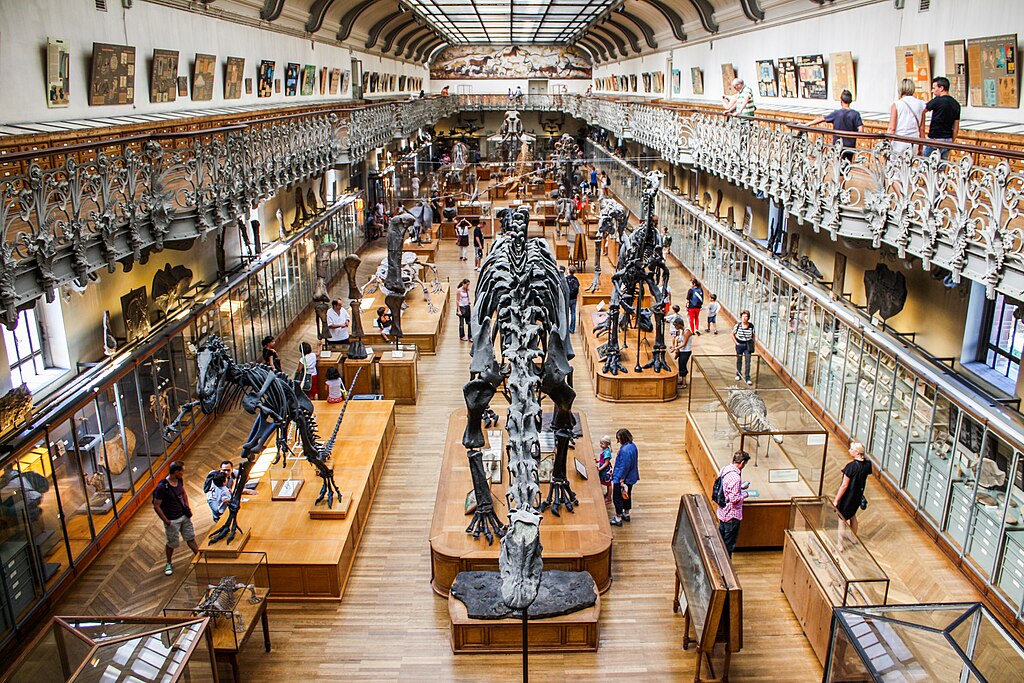

Architectural Dinosaurs

The influence of Gothic Revival architecture on dinosaur reconstructions is one of the most unexpected crossovers in art history. Many 19th-century dinosaur illustrations feature creatures with elaborate spines, crests, and ornamental features that look suspiciously like cathedral buttresses and decorative stonework. This wasn’t coincidental – the same artistic sensibilities that created ornate Victorian buildings also shaped how people imagined prehistoric life. Dinosaurs were given architectural dignity, with carefully arranged poses that emphasized symmetry and grandeur rather than biological accuracy. Stegosaurus plates were often arranged like a Gothic fence, while Triceratops frills resembled decorative shields from medieval heraldry. The result was a collection of “noble” dinosaurs that looked like they had been designed by the same people who built Victorian monuments. This architectural approach to paleontology created some of the most visually striking – if scientifically questionable – dinosaur art ever produced.

The Upright Walking Myth

One of the most persistent errors in early dinosaur reconstruction was the assumption that all large dinosaurs walked upright like humans or birds. This wasn’t just an artistic choice – it was based on fundamentally wrong assumptions about dinosaur anatomy and behavior. Victorian scientists, influenced by the Great Chain of Being concept, believed that upright posture was a sign of evolutionary advancement. Therefore, the largest dinosaurs must have walked on two legs to demonstrate their superiority over other reptiles. Artists depicted massive sauropods rearing up on their hind legs like circus elephants, despite the fact that such a pose would have been physically impossible for creatures weighing 50 tons or more. Even smaller dinosaurs were shown standing bolt upright, often with human-like postures and gestures that made them look like people in elaborate costumes. This upright obsession persisted for decades, creating a false image of dinosaurs as awkward, unnatural creatures struggling against their own anatomy.

Facial Expressions That Never Existed

Victorian paleo-artists had a remarkable talent for giving extinct reptiles facial expressions that would have made Shakespeare proud. Dinosaurs were illustrated with raised eyebrows, knowing smiles, looks of determination, and expressions of surprise that were completely impossible given their actual skull structure. The artists were unconsciously anthropomorphizing these creatures, projecting human emotions onto animals that had reptilian faces incapable of such expressions. Some illustrations show dinosaurs with almost comical looks of confusion or anger, as if they were cartoon characters rather than real animals. This tendency reached its peak with depictions of dinosaur “conversations” – groups of creatures apparently engaged in deep philosophical discussions, complete with appropriate facial expressions for each participant. The reality is that dinosaur faces were probably as expressionless as modern crocodiles or birds, but Victorian audiences wanted their monsters to have personality, and artists were happy to provide it.

The Color Catastrophe

With no way to determine the actual colors of extinct dinosaurs, 19th-century artists went absolutely wild with their color choices, creating some of the most psychedelic prehistoric art ever produced. Some dinosaurs were painted in brilliant greens and purples that would make a parrot jealous, while others sported stripes, spots, and patterns that seemed borrowed from tropical fish. The lack of scientific constraints meant that artistic taste – or lack thereof – was the only limiting factor. Some illustrations featured dinosaurs in colors that don’t exist anywhere in nature, creating creatures that looked more like alien visitors than earthly animals. The tendency was to make carnivorous dinosaurs dark and threatening, while herbivores got brighter, more “friendly” colors. This color coding system had no basis in biology but made perfect sense to Victorian moral sensibilities. Modern technology has actually revealed that some dinosaurs were indeed brightly colored, but the Victorian guesses were usually wrong in the most spectacular ways possible.

Domestic Dinosaur Life

Perhaps the most charming aspect of Victorian dinosaur art was its portrayal of prehistoric family life, complete with nuclear family structures that would have made any 19th-century household proud. Artists created elaborate scenes of dinosaur parents caring for their young with the same dedication and organization seen in human families. Baby dinosaurs were depicted as miniature adults, perfectly proportioned and well-behaved, rather than the awkward, vulnerable creatures they probably were. Some illustrations showed dinosaur families gathered around what looked like prehistoric dinner tables, with parents teaching their offspring proper behavior and social skills. The concept of dinosaurs as social, family-oriented creatures was actually quite progressive for its time, even if the execution looked like a Victorian family portrait with reptilian characters. These domestic scenes reflected contemporary ideals about family structure and child-rearing, projecting 19th-century values onto creatures that lived millions of years before humans existed.

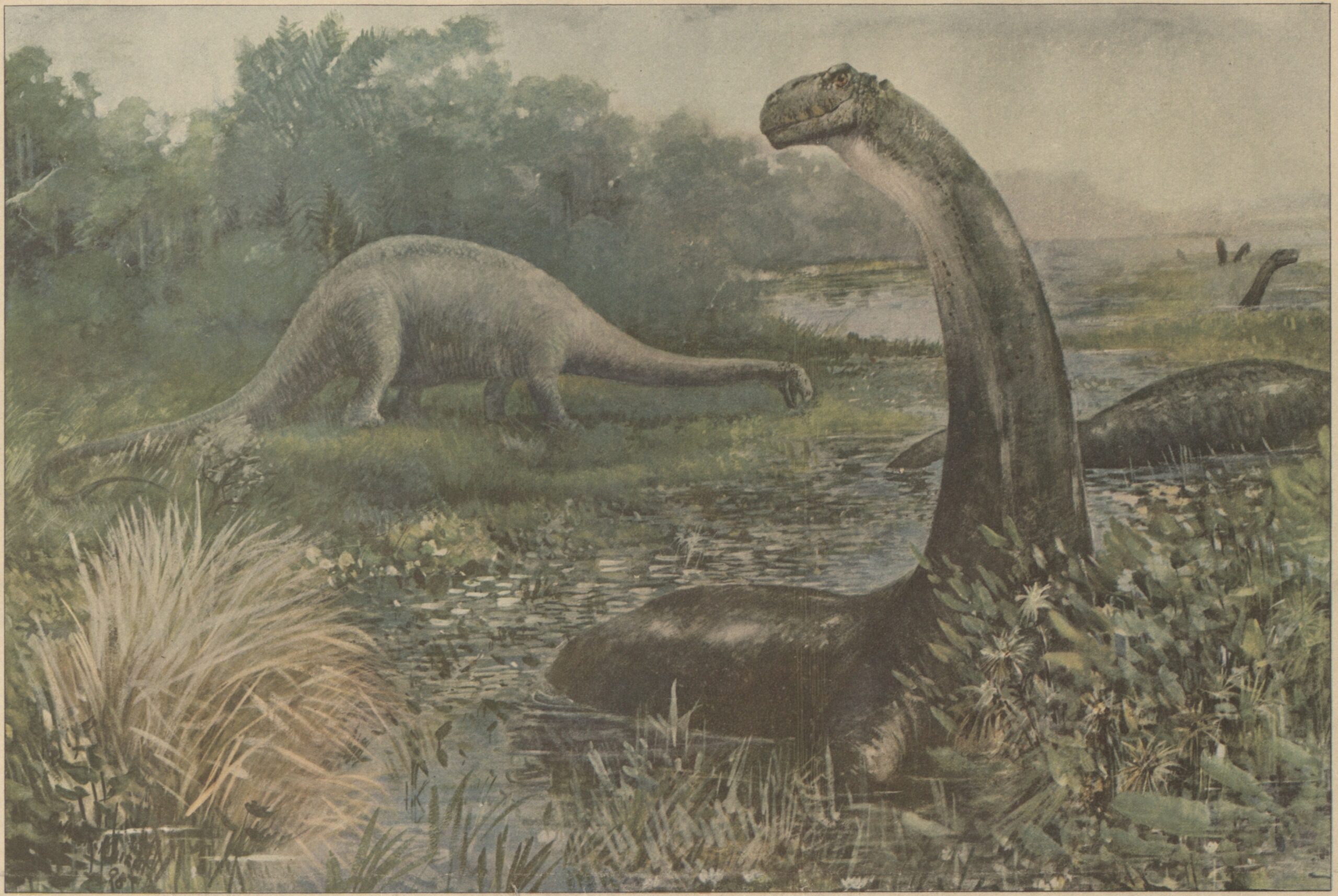

The Swamp Dweller Misconception

Victorian paleontologists were convinced that the largest dinosaurs spent most of their time wallowing in swamps like oversized hippos, and artists dutifully illustrated these aquatic lifestyle fantasies. Massive sauropods were shown neck-deep in murky water, supposedly because they were too heavy to support their own weight on land. This aquatic theory led to some beautifully atmospheric artwork featuring dinosaurs in lush, swampy landscapes that looked more like tropical vacation destinations than prehistoric ecosystems. The problem was that this entire concept was wrong – sauropods were perfectly capable of living on dry land and probably avoided deep water whenever possible. But the swamp theory persisted because it solved the weight problem that Victorian scientists couldn’t otherwise explain. Artists created elaborate underwater feeding scenes, showing dinosaurs using their long necks like snorkels while their bodies remained safely submerged. These aquatic dinosaur illustrations were often the most artistically successful pieces of the era, even though they depicted behavior that never actually occurred.

Monster Movie Influences

The dramatic, often theatrical poses of dinosaurs in 19th-century art had a profound influence on early monster movies and continue to shape popular culture today. Artists weren’t just creating scientific illustrations – they were designing characters for the greatest drama never filmed. Dinosaurs were posed like actors on a stage, with dramatic lighting effects and carefully chosen backgrounds that emphasized their size and power. Some illustrations featured dinosaurs in mid-roar, with expressions of rage that would later be copied by movie monsters for decades to come. The tendency to show dinosaurs in conflict, either with each other or with their environment, created a template for prehistoric action scenes that Hollywood would later exploit endlessly. These artistic choices weren’t based on any scientific evidence about dinosaur behavior, but they were incredibly effective at capturing public imagination. The legacy of Victorian dinosaur drama can still be seen in modern movies, where prehistoric creatures are portrayed as larger-than-life characters rather than simply animals.

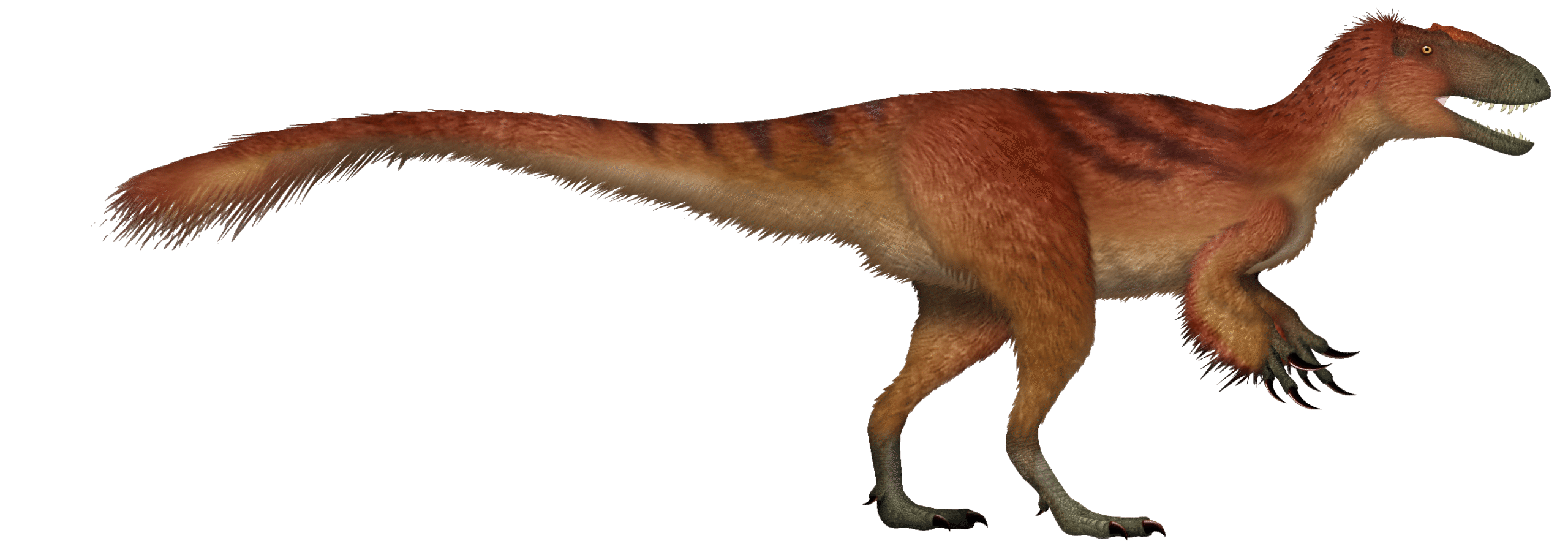

When Artists Became Prophets

Ironically, some of the wildest guesses made by 19th-century paleo-artists turned out to be surprisingly accurate predictions of discoveries that wouldn’t be made for another century. Artists who gave dinosaurs feathers were laughed at by scientists of their day, but we now know that many dinosaurs were indeed feathered. The occasional illustration showing dinosaurs in active, bird-like poses was dismissed as fantasy, but modern research has confirmed that many dinosaurs were highly active, warm-blooded creatures. Some artists even depicted dinosaur parents caring for their young in ways that seemed overly sentimental at the time but have since been confirmed by fossil evidence. These accidental accuracies weren’t based on scientific insight – they were often just artistic choices that happened to align with biological reality. The lesson here is that sometimes imagination and artistic intuition can reveal truths that rigid scientific thinking might miss, even if the reasoning behind the art was completely wrong.

The Legacy of Beautiful Mistakes

The wonderfully incorrect dinosaur art of the 19th century did something that perfectly accurate scientific illustrations might never have accomplished – it fired the public imagination and created a lasting fascination with prehistoric life that continues today. These artistic mistakes weren’t failures; they were stepping stones on the path to better understanding. Every wrong guess taught scientists something valuable about what questions to ask and what assumptions to challenge. The dramatic, emotionally engaging artwork of the Victorian era established dinosaurs as cultural icons rather than just scientific curiosities. Without these beautiful mistakes, we might never have developed the passionate interest in paleontology that drives modern research and discovery. The artists who gave dinosaurs bunny ears and kangaroo poses weren’t just getting things wrong – they were creating a bridge between the scientific world and popular imagination that continues to inspire new generations of researchers and enthusiasts.

Looking back at these Victorian dinosaur portraits today, it’s easy to laugh at their obvious mistakes and outdated assumptions. But these artists were doing something remarkable – they were trying to bring the deep past back to life with nothing but fragments of bone and boundless imagination. Their “mistakes” tell us as much about human nature and the power of artistic vision as they do about prehistoric life. What other scientific “facts” of our own era might future generations find equally amusing?