Picture this: Earth 252 million years ago, a planet still recovering from the most devastating extinction event in history. The Permian-Triassic extinction wiped out 90% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates. But from this apocalyptic wasteland, something extraordinary began to emerge. Nature, it seems, was about to embark on one of its most creative phases ever. The Triassic period became a biological laboratory where evolution went wild, producing creatures so bizarre they’d make modern animals look positively ordinary.

The World’s Most Experimental Laboratory

The Triassic period stretched from about 252 to 201 million years ago, and it was unlike anything Earth had experienced before or since. With ecological niches suddenly vacant after the Great Dying, evolution had a blank canvas to work with. Think of it like a massive creative explosion after a restrictive period – nature was free to experiment without the usual competitive constraints.

The climate was hot and humid, with no polar ice caps and tropical conditions extending almost to the poles. This greenhouse world created perfect conditions for rapid evolution and diversification. Pangaea, the supercontinent, was still largely intact, allowing species to spread across vast landmasses and evolve in isolation.

What makes the Triassic truly special is how evolution seemed to throw caution to the wind. Without established predator-prey relationships and ecological hierarchies, creatures could evolve into forms that would be completely impractical in today’s world. It was nature’s time to get weird.

Tanystropheus: The Giraffe-Necked Marine Reptile

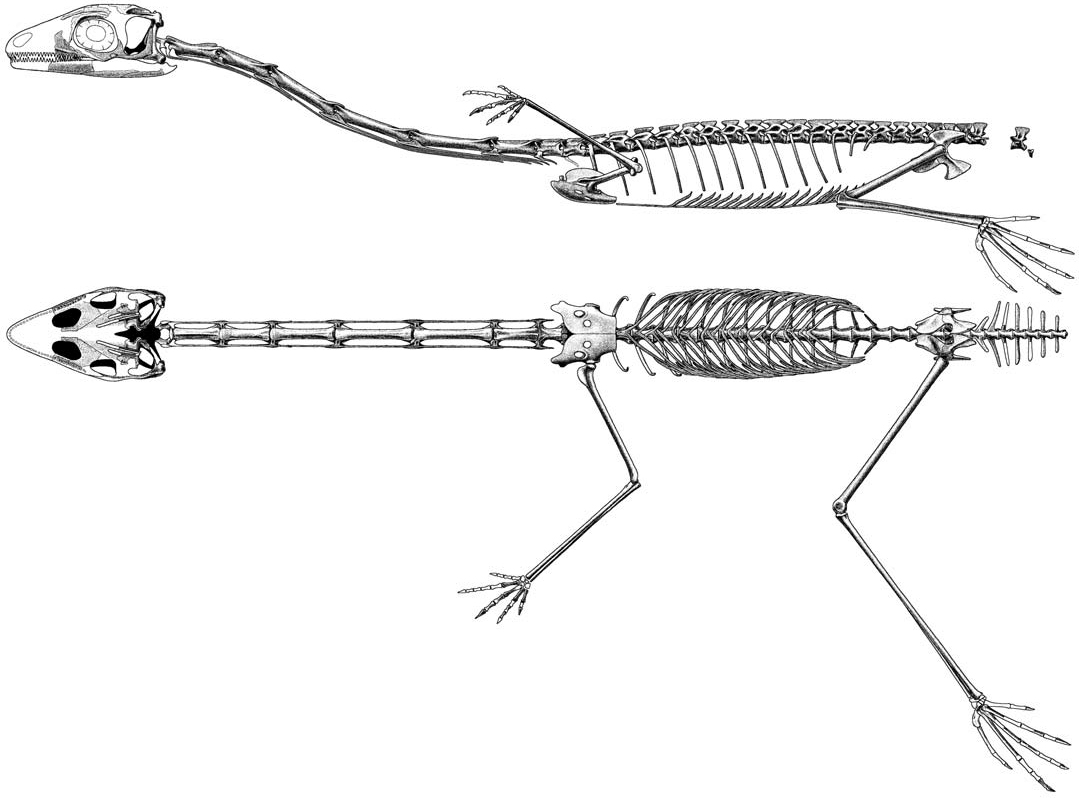

Imagine a creature that looks like someone took a lizard and stretched its neck to impossible proportions – that’s Tanystropheus for you. This marine reptile had a neck that made up half of its entire 20-foot body length, with some specimens reaching necks over 10 feet long. It’s like nature decided to create the world’s most impractical fishing rod and then made it alive.

Recent studies have revealed that Tanystropheus was a skilled swimmer, using its ridiculous neck as a fishing apparatus. The creature would keep its body hidden while extending its neck to snatch fish and squid from the water. Picture a snake with flippers, and you’re getting close to this aquatic oddity.

What’s truly mind-blowing is that juvenile and adult Tanystropheus had completely different lifestyles. Young ones lived in shallow coastal waters, while adults ventured into deeper seas. It’s as if evolution created a creature that changed its entire life purpose as it grew up.

Desmatosuchus: The Crocodile That Thought It Was a Tank

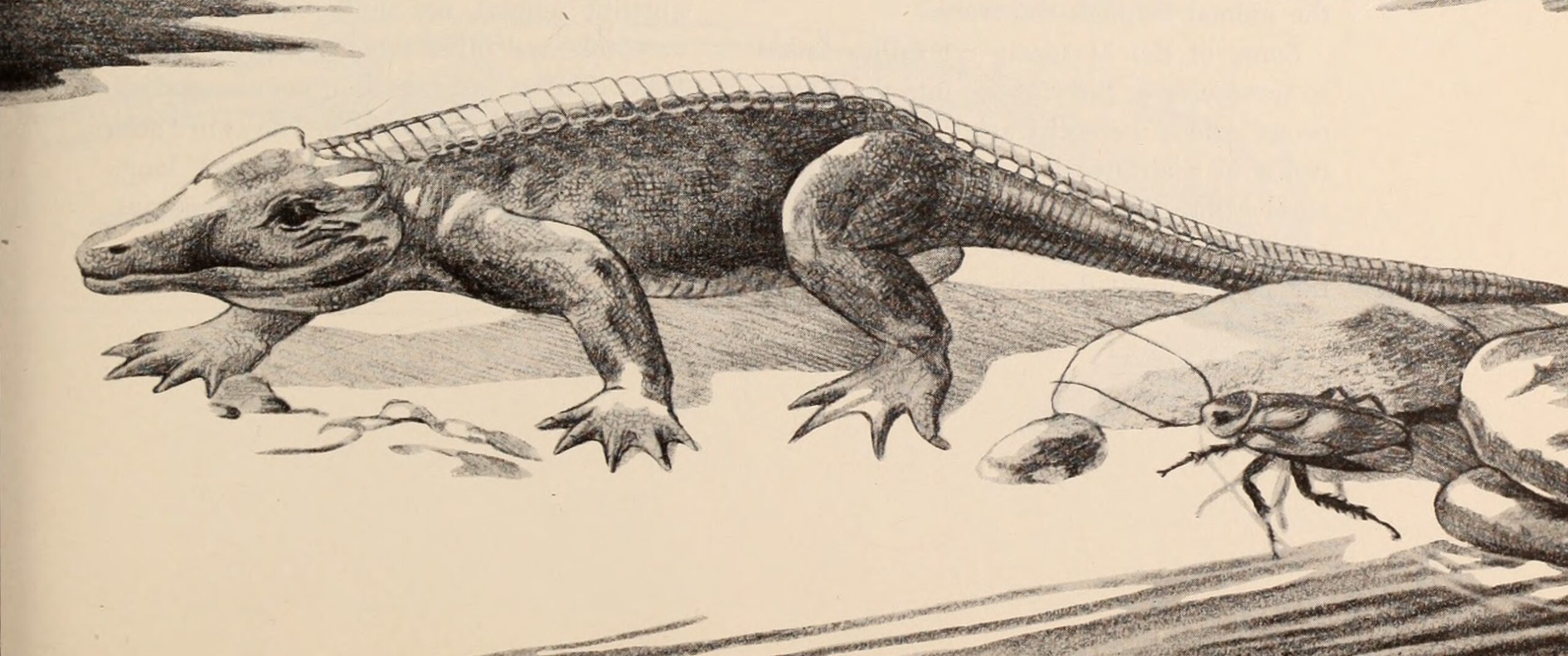

Meet Desmatosuchus, a creature that looked like someone crossed a crocodile with a medieval knight’s armor. This massive aetosaur stretched up to 16 feet long and was covered head to tail in thick, bony plates called scutes. But here’s the kicker – despite looking like the ultimate predator, this armored beast was a plant-eater.

The armor plating of Desmatosuchus was so extensive that it covered even its belly, making it look like a walking fortress. Some specimens had decorative spikes and ridges that would make a punk rocker jealous. This heavy armor made the animal incredibly slow, but virtually invulnerable to attack.

What makes Desmatosuchus truly bizarre is its pig-like snout, perfect for rooting around in soil for plants and tubers. Imagine a heavily armored tank that spends its time peacefully grazing – that’s the contradiction that was Desmatosuchus. It’s proof that in the Triassic, even the most fearsome-looking creatures could be gentle giants.

Sharovipteryx: The Backwards Flying Experiment

If you think modern flying squirrels are weird, wait until you meet Sharovipteryx. This tiny reptile, about the size of a sparrow, had one of the most unusual flight adaptations ever discovered. Instead of wing membranes stretching from its arms like bats or birds, Sharovipteryx had its flight membranes attached to its elongated hind legs.

Picture a lizard doing a permanent split while gliding through the air – that’s essentially what Sharovipteryx looked like in flight. Its front legs were tiny and virtually useless, while its back legs were enormously elongated to support the wing membranes. It’s like evolution was experimenting with every possible way to achieve flight.

This backward approach to flying was so unusual that scientists initially thought the fossils were assembled incorrectly. The creature represents one of evolution’s most creative solutions to the challenge of aerial locomotion, proving that there’s more than one way to conquer the skies.

Atopodentatus: The Hammerhead Herbivore

Atopodentatus uuniqueliterally means “unique strange tooth,” and boy, does it live up to that name. This marine reptile had one of the most bizarre skull shapes ever discovered – imagine a hammerhead shark, but instead of a hammer, it had a zipper-like mouth filled with hundreds of tiny teeth.

The creature’s skull was split down the middle, creating a distinctive zipper-mouth appearance that paleontologists initially couldn’t figure out. It turns out this weird mouth was perfectly adapted for filter-feeding, like a prehistoric whale. The split allowed water to flow through while trapping algae and small organisms on the needle-like teeth.

What’s particularly fascinating is that Atopodentatus represents one of the earliest experiments in filter-feeding among reptiles. At about 9 feet long, it was like a reptilian vacuum cleaner, cruising through ancient seas and filtering out microscopic meals. This adaptation was so successful that it evolved independently in several other marine reptile groups.

Effigia: The Crocodile That Ran Like an Ostrich

Effigia O’Keeffe was a crocodile relative that decided running was more important than swimming. This bizarre creature had long, slender legs built for speed, a toothless beak, and a lifestyle that was more bird than crocodile. At about 6 feet long, it looked like someone put a crocodile head on an ostrich’s body.

The most shocking thing about Effigia is that it was completely bipedal – it ran around on its hind legs like a feathered dinosaur, despite being a crocodile relative. Its front limbs were reduced to tiny, almost useless appendages. This creature proves that the crocodile body plan is far more flexible than we ever imagined.

Effigia’s toothless beak suggests it was either an herbivore or ate very soft foods like insects and small animals. The combination of bipedal locomotion and beak-like jaws represents one of evolution’s most surprising convergences with later dinosaur designs. It’s like nature was beta-testing the theropod dinosaur concept millions of years early.

Henodus: The Turtle That Forgot How to Swim

Henodus Chelyops was a turtle that seemed to have an identity crisis. While most turtles are reasonably good swimmers, Henodus was built like a floating coffee table with flippers. This marine turtle was almost perfectly square when viewed from above, with a completely flat shell that made it look more like a piece of furniture than a living animal.

The creature’s shell was covered in a mosaic of small, hexagonal plates that gave it a distinctly geometric appearance. Its head was tiny compared to its body, and its beak was perfectly adapted for filter-feeding on small organisms. Imagine a turtle-shaped pool float that could swim, and you’ve got Henodus.

What makes Henodus truly odd is that it represents a completely different approach to aquatic life among turtles. Instead of being streamlined for swimming, it was built for stability and efficient feeding. This turtle was essentially a living plankton net, floating through shallow seas and filtering food from the water.

Longisquama: The Ribbon-Winged Enigma

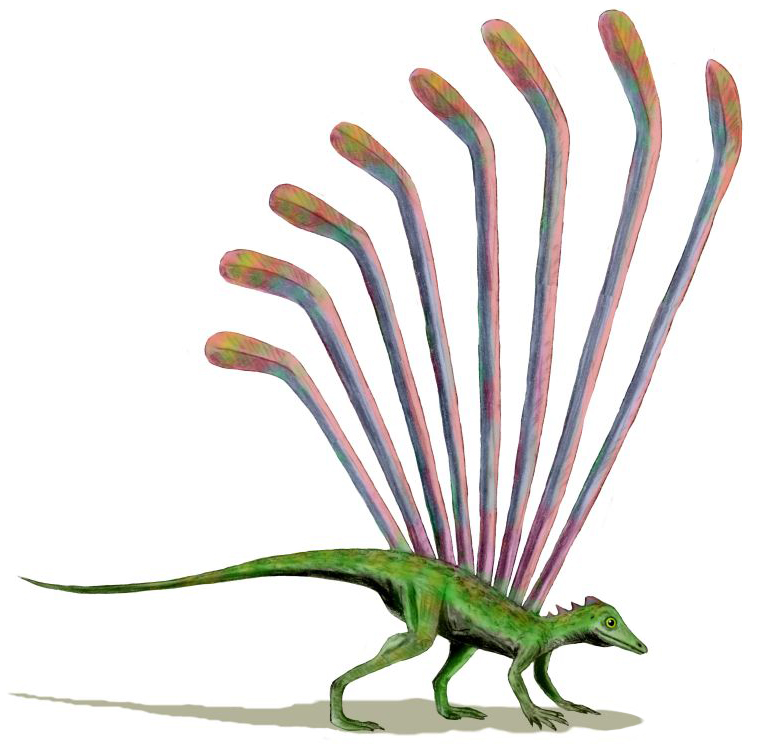

Longisquama insignis might be the most controversial creature on this list, mainly because scientists still can’t agree on what those things on its back were. This small reptile had a series of long, ribbon-like structures running down its spine that looked like nothing seen before or since in the animal kingdom.

Some scientists think these structures were proto-feathers, making Longisquama a crucial link in the evolution of flight. Others believe they were elongated scales used for display or thermoregulation. The most exotic theory suggests they were primitive wings used for gliding between trees.

The mystery of Longisquama’s back appendages represents one of paleontology’s most enduring puzzles. Whether they were feathers, scales, or something else entirely, they demonstrate just how experimental evolution was during the Triassic. This tiny creature might hold the key to understanding how flight evolved, or it might just be another example of Triassic weirdness.

Drepanosaurus: The Monkey-Lizard with a Claw

Drepanosaurus unguicaudatus was built like a reptilian Swiss Army knife, with specialized tools for every occasion. This arboreal reptile had a prehensile tail with a massive claw at the end, elongated fingers perfect for gripping branches, and a lifestyle that was more monkey than lizard.

The creature’s most distinctive feature was its tail claw, which was enormous compared to its body size. This claw was likely used for stripping bark from trees to get at insects and larvae underneath. Combined with its grasping hands and feet, Drepanosaurus was perfectly adapted for life in the trees.

What makes Drepanosaurus particularly fascinating is how it convergently evolved many of the same adaptations as modern primates. The combination of grasping hands, prehensile tail, and arboreal lifestyle shows that the “monkey” body plan is so successful that evolution has stumbled upon it multiple times. This reptile was essentially a monkey with scales, living in forests 220 million years ago.

Paracyclotosaurus: The Salamander That Grew Up Wrong

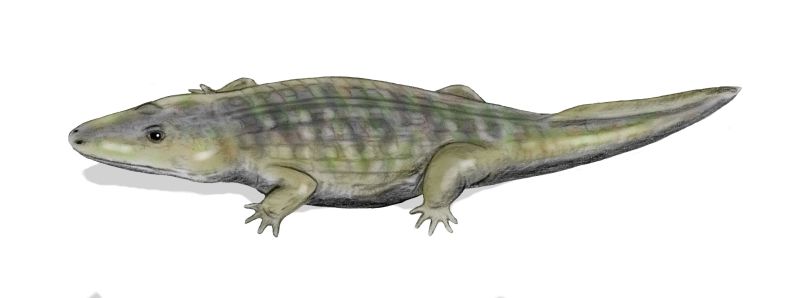

Paracyclotosaurus was a temnospondyl amphibian that took the concept of “never growing up” to an extreme. This creature retained juvenile characteristics throughout its life, including external gills and a purely aquatic lifestyle. At over 6 feet long, it was like a giant salamander that refused to metamorphose into an adult form.

The most striking feature of Paracyclotosaurus was its massive, flat head that made up nearly a quarter of its body length. This oversized skull was packed with teeth and gave the creature a distinctly prehistoric appearance. Its body was built for life in the water, with a powerful tail for swimming and relatively weak limbs.

What makes Paracyclotosaurus particularly interesting is that it represents a successful evolutionary strategy of permanent juvenility. By retaining larval characteristics, these amphibians could exploit aquatic niches that were unavailable to their fully metamorphosed relatives. It’s a reminder that sometimes staying young is the key to survival.

Vancleavea: The Armored Eel That Wasn’t

Vancleavea Campi looked like someone tried to create an armored eel but got confused halfway through. This semi-aquatic reptile had an elongated body covered in bony armor, tiny limbs, and a lifestyle that was part crocodile, part snake. At about 4 feet long, it was perfectly adapted for life in shallow water and muddy shores.

The creature’s armor was arranged in neat rows along its back and sides, giving it a distinctly segmented appearance. Its limbs were so small they were almost useless for walking on land, but they were perfect for steering while swimming. The tail was laterally compressed like a fish’s, indicating a strong swimming ability.

Vancleavea’s unusual body plan represents another example of Triassic experimentation with aquatic lifestyles. The combination of heavy armor and semi-aquatic habits suggests it lived in dangerous waters where protection was more important than speed. It’s like evolution was trying to create the perfect ambush predator for shallow water environments.

Sinosaurosphargis: The Turtle That Wasn’t a Turtle

Sinosaurosphargis yunguiensis looked almost exactly like a turtle, complete with a shell-like carapace and a beak-like mouth. The only problem? It wasn’t a turtle at all. This marine reptile independently evolved turtle-like features, creating one of the most striking examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record.

The creature’s shell was made up of overlapping bony plates that provided excellent protection from predators. Its limbs were modified into flippers for swimming, and its beak was perfectly adapted for crushing shellfish and other hard-shelled prey. At about 3 feet long, it was the perfect size for navigating shallow coastal waters.

What makes Sinosaurosphargis truly remarkable is how closely it resembled true turtles despite being only distantly related. This parallel evolution demonstrates that the turtle body plan is so successful that nature has reinvented it multiple times. It’s proof that sometimes the best solutions to life’s challenges are discovered independently by completely different lineages.

Kuehneosaurus: The Gliding Lizard with Airplane Wings

Kuehneosaurus was a small lizard that took gliding to the next level with wing-like membranes supported by extremely elongated ribs. Unlike modern gliding lizards that have simple skin flaps, Kuehneosaurus had complex wing structures that looked remarkably similar to airplane wings.

The creature’s ribs were so elongated that they extended far beyond its body, creating a wing surface that was proportionally larger than any modern gliding animal. These wings were probably covered with skin membranes that allowed for controlled gliding between trees. At only about 2 feet long, Kuehneosaurus was light enough to be an efficient glider.

What sets Kuehneosaurus apart from other gliding reptiles is the sophistication of its wing structure. The elongated ribs could be folded back against the body when not in use, allowing the animal to move normally on the ground. This represents one of the most advanced gliding adaptations in the reptile fossil record, rivaling even modern flying squirrels in complexity.

The Legacy of Triassic Experimentation

The bizarre creatures of the Triassic period represent one of the most creative phases in Earth’s history. These oddball animals weren’t just evolutionary dead ends – they were nature’s way of testing every possible solution to the challenges of life. Many of their innovations would later be refined and perfected by more familiar groups of animals.

The Triassic experiments laid the groundwork for many of the body plans we see in modern animals. The flight adaptations of creatures like Sharovipteryx and Kuehneosaurus prefigured the later evolution of pterosaurs, birds, and bats. The filter-feeding strategies of Atopodentatus would be rediscovered by whales and other marine mammals millions of years later.

Perhaps most importantly, these creatures remind us that evolution is not a linear progression toward perfection, but a constant process of experimentation and adaptation. The “failures” of the Triassic are just as important as the successes because they show us the full range of possibilities that life can explore. In a world that was rebuilding itself after the greatest extinction event in Earth’s history, anything was possible – and for a brief, shining moment, nature made the most of that opportunity.