For over a century, paleoartists have given the public visual interpretations of prehistoric creatures that shaped our collective imagination. These artistic renderings have informed our understanding of dinosaurs and other extinct species, but many of these widely accepted depictions were spectacularly incorrect. Based on limited fossil evidence and contemporary scientific understanding, paleoartists created images that seemed plausible at the time but have since been thoroughly debunked. The history of paleoart is filled with fascinating examples of artistic license, misinterpreted evidence, and outdated science that led to misconceptions that persisted for decades, sometimes becoming so ingrained in popular culture that the correct versions now seem strange to us. Let’s explore some of the most notable cases where paleoartists got it completely wrong, yet their visions were embraced by both the scientific community and the public.

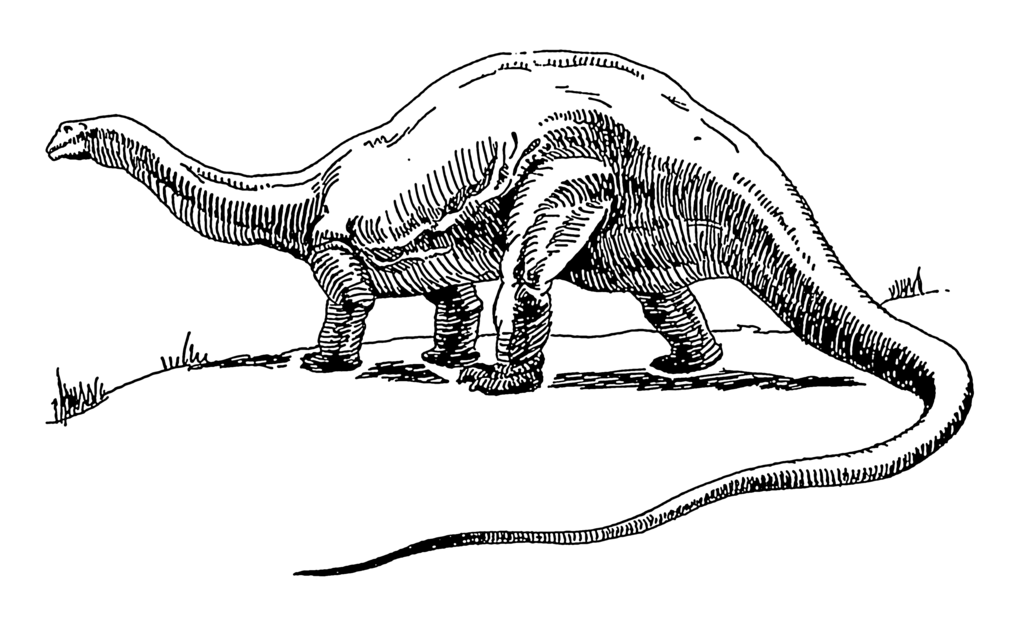

The Upright Tail-Dragging Dinosaur Trope

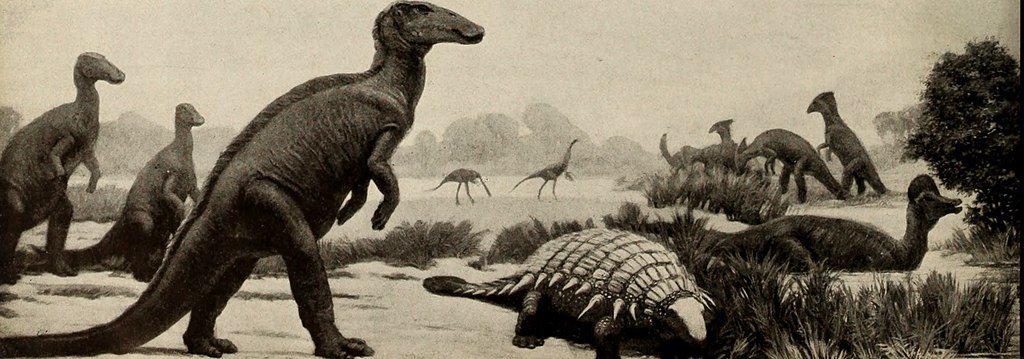

Perhaps the most persistent paleoart mistake was the portrayal of dinosaurs as lumbering, tail-dragging creatures with an upright posture similar to modern lizards. Artists like Charles R. Knight and Rudolph Zallinger created influential murals showing Tyrannosaurus rex and other theropods in unnaturally vertical poses with their tails dragging on the ground. This interpretation dominated museum displays, textbooks, and films for most of the 20th century. Fossil evidence, however, clearly shows that dinosaurs like T. rex had a horizontal posture with spines parallel to the ground and their tails held aloft as counterbalances. The tail-dragging misconception likely arose from comparisons to modern reptiles and was reinforced by early museum mountings that used this posture for structural stability rather than anatomical accuracy. It wasn’t until the “Dinosaur Renaissance” of the 1970s that this error began to be widely corrected, though the tail-dragging image persists in older media.

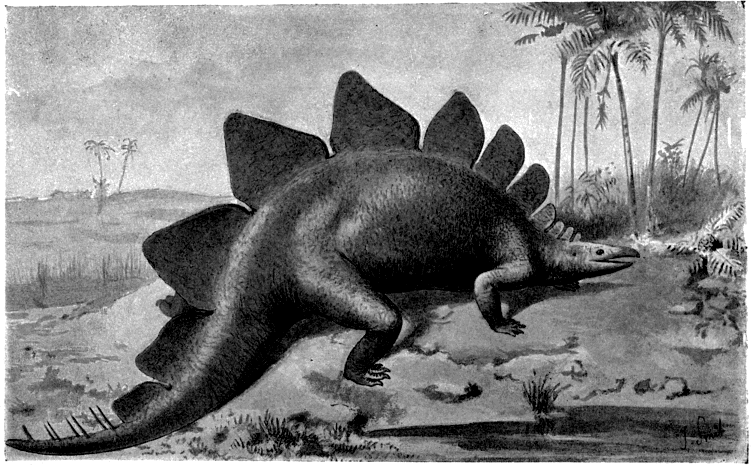

Naked Dinosaurs in a Reptilian Light

For decades, paleoartists depicted all dinosaurs with scaly, reptilian skin devoid of any feathers or filaments. This representation stemmed from the early classification of dinosaurs as reptiles and the limited fossil evidence of soft tissue. The discovery of feathered dinosaur fossils in China’s Liaoning Province in the 1990s revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur appearance, proving that many theropods were covered in feathers or feather-like structures. Despite this evidence, popular culture has been slow to adopt feathered dinosaurs, with films like Jurassic Park continuing to show naked, scaly creatures even in their most recent installments. The resistance to feathered dinosaurs illustrates how deeply entrenched the original paleoart interpretations became in public consciousness. Today, accurate representations show many dinosaur species with varying degrees of feather coverage, from simple filaments to full plumage, particularly in species closely related to birds.

The Brontosaurus Body-Swap Scandal

One of the most famous paleoart errors involves the beloved Brontosaurus, which for years was depicted with the wrong head. When paleontologist O.C. Marsh described Brontosaurus in 1879, the skeleton lacked a skull, so he added a skull from another discovery that was actually from a Camarasaurus—a completely different sauropod species. This mistaken composite was rendered in countless paintings, museum displays, and children’s books, showing Brontosaurus with a short, boxy skull. The error wasn’t widely corrected until the 1970s, when scientists determined that Brontosaurus should have had an Apatosaurus-like skull, l—longer and more horse-like in appearance. Interestingly, this mistake was compounded by another error: for decades, scientists considered Brontosaurus to be an invalid genus, synonymous with Apatosaurus, only for research in 2015 to re-establish Brontosaurus as distinct. This case demonstrates how paleoart can perpetuate scientific errors and how difficult it can be to correct public perception once a particular image becomes established.

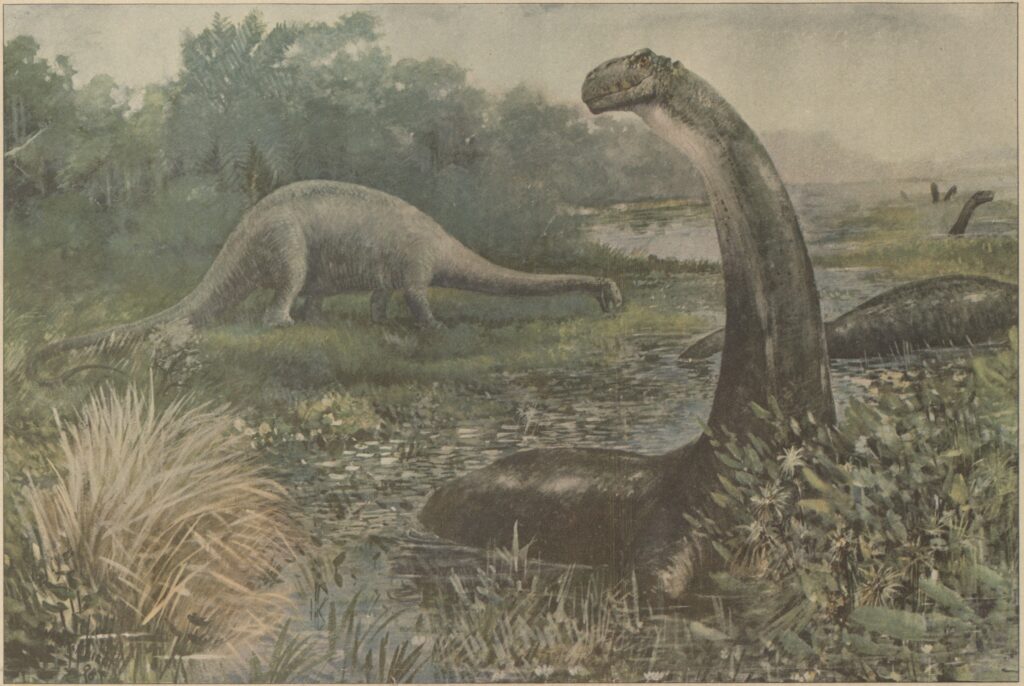

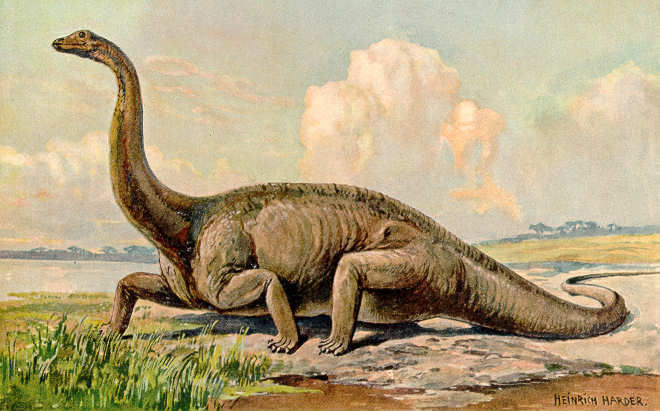

Amphibious Dinosaurs and the Swamp-Dwelling Sauropod Myth

Throughout much of the 20th century, paleoartists regularly depicted sauropods like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus as semi-aquatic creatures that lived primarily in swamps and lakes. These massive animals were shown half-submerged in water, using the buoyancy to support their enormous weight. Zdeněk Burian’s influential paintings cemented this interpretation in the public mind, showing sauropods with their bodies partially underwater and only their heads and necks emerging above the surface. This misconception stemmed from the early belief that sauropods were too large to support their weight on land, combined with their nostril placement high on their heads. Later research thoroughly debunked this idea, as a detailed study of sauropod limb structure, trackways, and lung anatomy revealed they were fully terrestrial animals with column-like legs perfectly adapted for supporting their weight on land. The high-placed nostrils turned out to be related to resonating chambers for vocalization rather than snorkels for breathing while submerged. Despite this correction, the image of swamp-dwelling sauropods persisted in paleoart for decades.

The Cold-Blooded Dinosaur Assumption

For much of paleoart history, dinosaurs were depicted as slow-moving, cold-blooded reptiles similar to modern lizards or crocodiles. This portrayal influenced how artists showed dinosaur behavior, posture, and activity levels, typically rendering them as sluggish creatures lying around conserving energy. Beginning in the 1960s, paleontologist Robert Bakker and others began challenging this view with evidence suggesting dinosaurs were warm-blooded, active animals more akin to birds than reptiles. Modern paleoart now shows dinosaurs in dynamic poses, engaging in complex behaviors, and exhibiting the active lifestyles consistent with endothermy. The physiology debate continues in scientific circles, with current consensus suggesting various dinosaur groups likely had different metabolic strategies, ranging from fully endothermic to mesothermic. This shift represents one of the most fundamental changes in how dinosaurs are visualized, transforming them from sluggish reptiles to active, dynamic creatures—a prime example of how scientific understanding directly impacts artistic representation.

The Oversized Prehistoric Mammal Phenomenon

Prehistoric mammals have frequently been victims of exaggerated proportions in paleoart, with creatures like Megatherium (giant ground sloth) and Smilodon (saber-toothed cat) often portrayed as much larger than they were. Early paleoartists regularly depicted Smilodon as a monster-sized cat, when in reality, most species were roughly the size of modern lions or tigers. Similarly, while Megatherium was certainly impressive at around 4-6 meters tall when standing on its hind legs, older illustrations often exaggerated its size to appear elephant-like in overall bulk. This size inflation seems to stem from the common desire to portray prehistoric animals as more dramatic and fearsome than their modern counterparts. Another famous example is Deinotherium, an extinct proboscidean often shown as dramatically larger than modern elephants in classic paleoart, though more accurate measurements place most species at comparable sizes to modern African elephants. These size exaggerations have slowly been corrected in modern paleoart, though the “larger than life” perception of prehistoric mammals persists in popular culture.

The Neanderthal as Stooped Caveman Stereotype

The depiction of Neanderthals represents one of the most persistent and harmful misrepresentations in paleoart. Following the discovery of the first Neanderthal specimens in the 19th century, artists quickly established the image of these human relatives as stooped, slouching, brutish cavemen with limited intelligence. This mischaracterization stemmed partly from the examination of an elderly, arthritic Neanderthal specimen whose pathology was mistakenly assumed to be typical of the species. The famous paleoartist Charles R. Knight and others perpetuated this stereotype in influential illustrations that shaped public perception for generations. Modern scientific analysis has completely overturned this view, showing that Neanderthals stood fully upright, had brains larger than modern humans, created sophisticated tools and art, and engaged in complex cultural practices including ceremonial burials. Contemporary paleoart now portrays Neanderthals as the intelligent, capable hominids they were, though the “caveman” stereotype continues to influence popular culture references and remains one of the most difficult paleoart errors to fully correct in the public consciousness.

The Mistakenly Monstrous Marine Reptiles

Marine reptiles from the Mesozoic era, particularly ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs, and mosasaurs, have been subject to fantastic exaggeration in historical paleoart. Early representations often gave these creatures exaggerated features like impossibly flexible necks, dragon-like appearances, or the ability to rear out of water like sea serpents. Victorian-era paleoartist Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins created influential depictions of plesiosaurs rearing their entire necks and torsos out of water, a physically impossible feat given their anatomy and weight distribution. Similar misrepresentations appeared in early illustrations of mosasaurs, which were frequently depicted as more serpentine and flexible than their actual skeleton would allow. Ichthyosaurs, despite having relatively good fossil evidence showing their dolphin-like appearance, were often given reptilian features inconsistent with their actual anatomy. Modern research has clarified the appearance and capabilities of these marine reptiles, showing ichthyosaurs as more streamlined and dolphin-like, plesiosaurs as unable to lift their necks high out of water, and mosasaurs as having more robust bodies with tail flukes rather than the serpentine forms once depicted.

The Pterosaur Identity Crisis

Flying reptiles known as pterosaurs have been consistently misrepresented in paleoart, often being incorrectly portrayed as dinosaurs or with anatomical features more closely resembling bats or birds. Early paleoartists like Zdeněk Burian and Rudolph Zallinger depicted pterosaurs with bat-like wing membranes attached to their legs, an arrangement now known to be incorrect for most species. Another common error was showing pterosaurs with an upright, bird-like posture when on the ground, when fossil evidence indicates they walked on all fours using their folded wings as front limbs. Perhaps most famously, pterosaurs like Pteranodon were often shown capable of grasping prey with their feet like birds of prey, despite lacking the anatomical adaptations for this behavior. The massive pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus was initially depicted as a soaring scavenger similar to a vulture, but more recent evidence suggests it was more likely a terrestrial stalker that hunted like a stork. These misrepresentations stem partly from the tendency to use familiar living animals as references and the fragmentary nature of pterosaur fossils, which made accurate reconstructions challenging.

The Prehistoric Plant Problem

The background vegetation in paleoart has often been as inaccurate as the animals themselves, with artists frequently populating prehistoric landscapes with plants from the wrong periods or environments. One of the most common errors has been including flowering plants (angiosperms) in Triassic and early Jurassic scenes, despite these plants not evolving until the mid-Cretaceous period. Early paleoartists regularly showed dinosaurs moving through landscapes filled with modern-looking trees, ferns, and palms, regardless of geological era or location. Another persistent mistake was depicting cycads—primitive palm-like plants—as the dominant vegetation across all dinosaur habitats, when in reality, the Mesozoic had diverse plant communities that varied greatly by region and period. Charles R. Knight’s influential murals, while groundbreaking for their time, often featured incorrect plant assemblages that mixed species from different periods. These botanical inaccuracies persisted because plant fossils received less attention than charismatic megafauna, and paleoartists often had limited botanical knowledge. Modern paleoart has become increasingly precise about plant life, with artists consulting paleobotanists to create time-appropriate floral settings.

The “Killer Dinosaur” Fixation

Paleoart has long been dominated by scenes of extreme violence and predation, with dinosaurs and other prehistoric creatures depicted in constant mortal combat. This “perpetual bloodbath” approach to prehistoric life peaked in the 1960s-1980s with artists like Rudolph Zallinger creating dramatic scenes of carnivores locked in battle or attacking prey. While predation certainly occurred in prehistoric ecosystems, the overwhelming focus on violent interactions greatly misrepresented the daily reality of dinosaur life, which, like modern animals, would have involved more time resting, socializing, foraging, and engaging in other non-predatory behaviors. This fixation on violence stemmed partly from commercial interests, as dramatic scenes sell books and capture public imagination more effectively than accurate depictions of everyday dinosaur activities. The predator bias also led to anatomical exaggerations, with carnivorous dinosaurs often given disproportionately large claws, teeth, and menacing features. Modern paleoartists have begun correcting this imbalance by depicting more diverse behaviors, including parental care, courtship, social interactions, and the natural behaviors that would have occupied most of a prehistoric animal’s time.

The Ever-Changing Face of Dinosaur Color

Until quite recently, dinosaur coloration in paleoart was based entirely on artistic license, with no scientific foundation. Early paleoartists like Charles R. Knight established a convention of depicting dinosaurs in muted earth tones—typically grays, browns, and olive greens—based largely on modern reptiles like crocodiles and komodo dragons. This color palette became the standard for dinosaur representation throughout most of the 20th century, creating a persistent image of dinosaurs as universally drab. Some artists broke from this convention, with children’s books often showing dinosaurs in bright primary colors, but these were considered even less scientifically plausible than the standard earth tones. The scientific reality remained that no one knew what colors dinosaurs displayed until the 2010s, when revolutionary studies of fossilized melanosomes (pigment-containing structures) began revealing actual colors in some exceptionally preserved fossils. We now know that some dinosaurs, like Microraptor, had iridescent black feathers similar to ravens, while others showed complex patterns and vibrant colors. Modern paleoart has embraced this new understanding, showing dinosaurs with the diverse coloration patterns found in their modern descendants, birds, while acknowledging that for most species, color remains speculative.

The Legacy of Incorrect Paleoart and Its Correction

Despite its many inaccuracies, historical paleoart holds immense value as a record of evolving scientific understanding. Each generation of paleoartists worked with the evidence available to them, creating the most plausible reconstructions possible given contemporary knowledge. The persistence of incorrect images—from tail-dragging T. rex to featherless raptors—demonstrates the powerful impact visual representation has on public understanding of science. Modern paleoartists face the dual challenge of creating scientifically accurate work while competing with entrenched, often incorrect images that feel more “right” to audiences raised on outdated depictions. The correction of paleoart errors has accelerated in recent decades thanks to new fossil discoveries, advanced research techniques like CT scanning, and closer collaboration between artists and scientists. Leading contemporary paleoartists like Julius Csotonyi, Emily Willoughby, and Mark Witton create meticulously researched reconstructions that balance scientific accuracy with aesthetic appeal. Social media has also democratized paleoart criticism, allowing specialists to quickly identify and correct inaccuracies. While public perception often lags behind scientific understanding, the growing emphasis on accuracy in museum displays, documentaries, and scientific illustration ensures that future generations will have a much more accurate visual concept of prehistoric life.

Conclusion

The history of paleoart reminds us that scientific visualization is always a product of its time, reflecting both the evidence available and the cultural context in which it’s created. As our understanding continues to evolve, so too will our artistic renderings of the prehistoric world, likely correcting errors we don’t yet recognize. The next time you see a dinosaur illustration or model, remember that what seems obvious today may be tomorrow’s outdated misconception, as science continually refines our window into the ancient past.