The skies 150 million years ago were a different world altogether. While today we take for granted the sight of birds soaring overhead, the Jurassic Period marked one of the most extraordinary chapters in the evolution of flight. This wasn’t just about pterosaurs gliding through prehistoric landscapes or early birds taking their first tentative flaps – it was about a perfect storm of environmental conditions, evolutionary pressure, and biological innovation that fundamentally changed life on Earth forever.

The Great Atmospheric Laboratory

Picture breathing air so rich in oxygen that your metabolism would go into overdrive within minutes. The atmospheric CO2 content was around seven times (1900 ppm) the preindustrial level while the average oxygen level was 26% (130% of modern level). The Jurassic atmosphere wasn’t just different from ours – it was a supercharged environment that made flight not only possible but advantageous for creatures that would never survive in today’s air.

This oxygen-rich atmosphere created conditions that seem almost fantastical by modern standards. The dinosaurs apparently breathed air that was much richer in oxygen than our air and lived in forests and grasslands that were far more combustible than ours. Think about what this meant for flying creatures: every breath delivered more fuel for their high-energy lifestyle, making sustained flight achievable even with primitive wing designs.

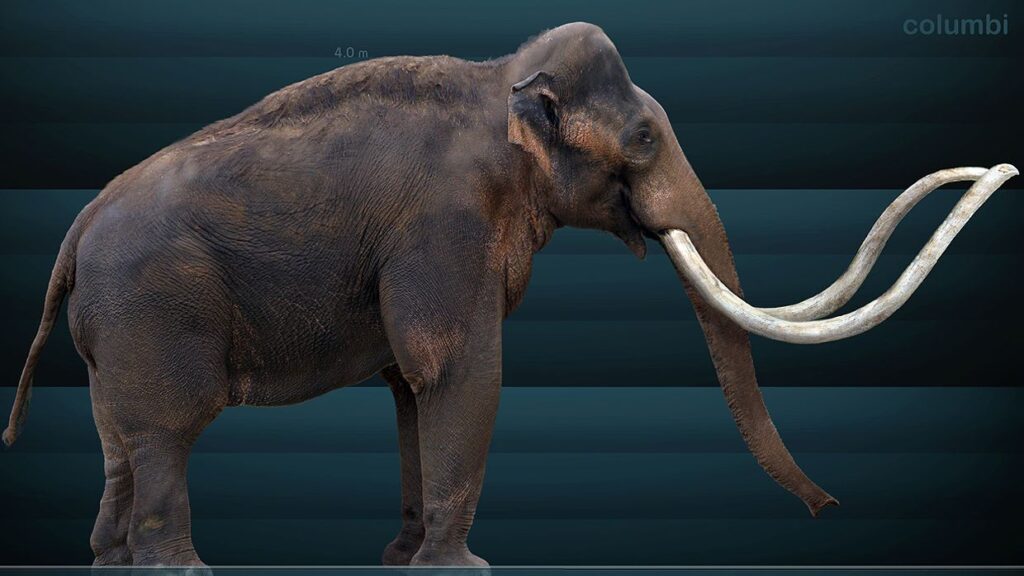

When Giants Ruled the Skies

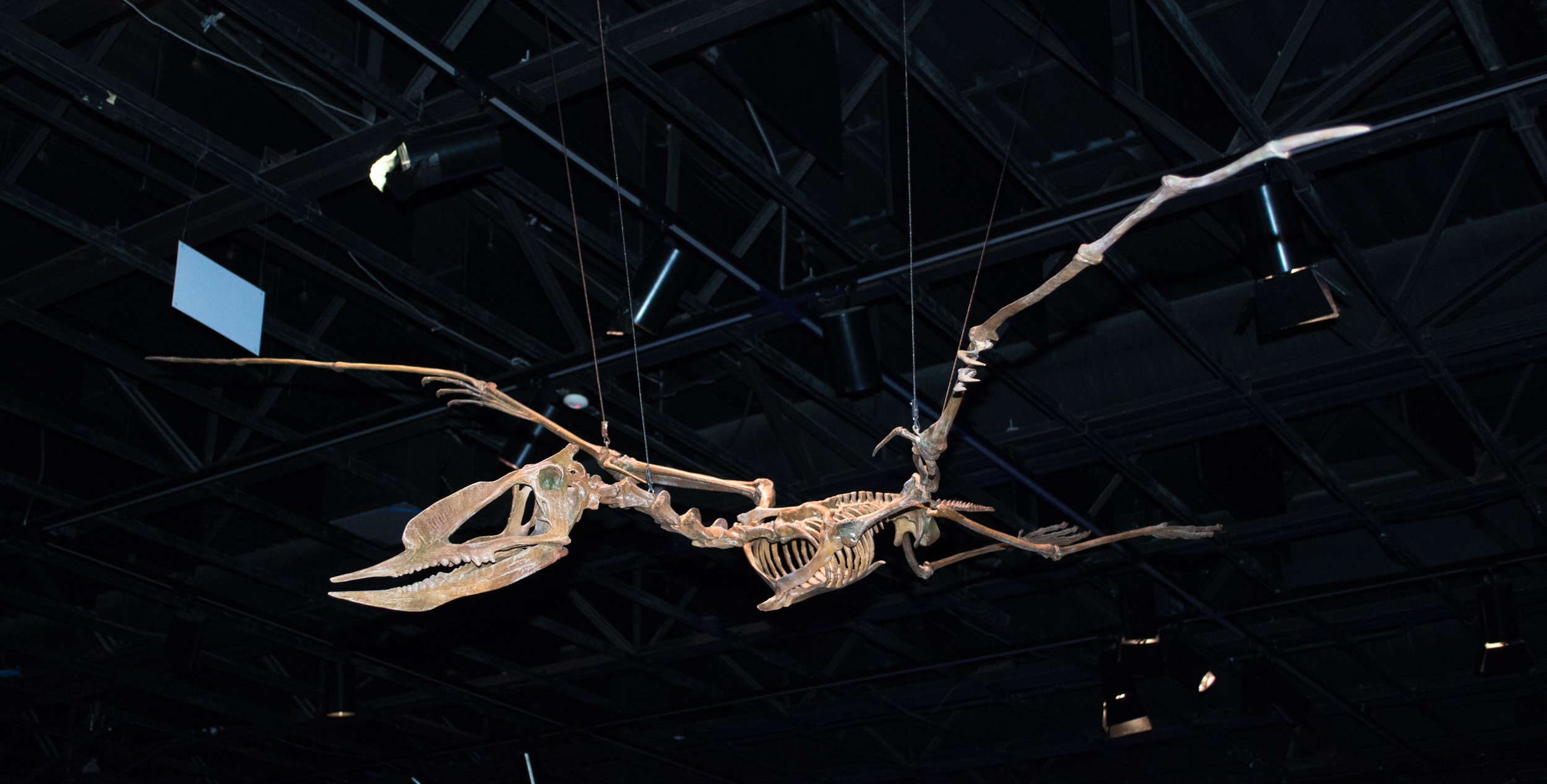

The most spectacular evidence of how atmospheric conditions influenced flight comes from the sheer size of Jurassic flying reptiles. Large pterosaurs of the Jurassic period had impressive wingspans, with some reaching over 20 feet. The well-known Pteranodon, though from the later Cretaceous period, had a maximum wingspan of about 23 feet. To put this in perspective, imagine a creature with wings spanning the length of a school bus effortlessly soaring through ancient skies.

These weren’t just oversized gliders struggling to stay airborne. But if anything, the pterosaurs were less well designed than modern birds. They lacked the birds’ efficient keelbone muscle structure and the aerodynamic advantages of feathers. Yet they dominated the skies for millions of years, suggesting that environmental conditions, particularly oxygen levels, played a crucial role in making their massive size feasible.

The Pterosaur Revolution

Pterosaurs are the earliest vertebrates known to have evolved powered flight. But what made the Jurassic Period so special for these flying reptiles wasn’t just that they existed – it was that they underwent their most dramatic evolutionary changes during this time. The rise of pterodactyloids occurred during the Jurassic period. Fossil records suggest they first appeared around 160 million years ago.

These advanced pterosaurs represented a revolutionary leap in flight technology. The pterodactyloids, a later subgroup, showcased slender, elongated wings and shortened tails. These evolutionary advancements marked the transition from the earlier, more primitive forms to highly efficient flying machines. The timing wasn’t coincidental – the Jurassic environment provided the perfect conditions for this evolutionary breakthrough.

The discovery of transitional forms like Darwinopterus has revealed how rapid this transformation was. Dated to the middle of the Jurassic Period, about 160 million years ago, the crow-sized pterosaur possessed a head and neck characteristic of the more-advanced pterodactyloids, whereas its remaining skeletal features were very similar to those found in more-primitive rhamphorhynchoid pterosaurs.

The Birth of True Birds

While pterosaurs were perfecting their membrane-based flight, another group was experimenting with an entirely different approach. The evolution of birds began in the Jurassic Period, with the earliest birds derived from a clade of theropod dinosaurs named Paraves. This wasn’t just another evolutionary side story – it was the birth of the most successful flying vertebrates in Earth’s history.

Archaeopteryx lived in the Late Jurassic around 150 million years ago, in what is now southern Germany, during a time when Europe was an archipelago of islands in a shallow warm tropical sea, much closer to the equator than it is now. This primitive bird emerged in an environment that was radically different from today’s world, with conditions that favored experimental flight adaptations.

The significance of Archaeopteryx extends far beyond its famous feathers. Paleontologists view Archaeopteryx as a transitional fossil between dinosaurs and modern birds. With its blend of avian and reptilian features, it was long viewed as the earliest known bird.

Feathers: The Game-Changing Innovation

The evolution of feathers represents one of the most remarkable innovations in the history of flight, and the Jurassic Period was when this technology reached its full potential. Others (like the dromaeosaurids and Archaeopteryx) have a vane-like structure in which the barbs are well-organized and locked together by barbules. This is identical to the feather structure of living birds.

But feathers didn’t evolve specifically for flight – they had multiple functions that made them incredibly versatile. As we have seen, the first, simplest, hair-like feathers obviously served an insulatory function. But in later theropods, such as some oviraptorosaurs, the feathers on the arms and hands are long, even though the forelimbs themselves are short. This suggests that feathers were being tested in various roles before flight became their primary function.

The complexity of feather evolution during the Jurassic reveals how environmental pressures shaped this innovation. Some species developed elaborate display structures, while others focused on aerodynamic properties that would eventually enable powered flight.

Climate and Geography: The Perfect Storm

The Jurassic world was a flight enthusiast’s paradise. Analyses of oxygen isotopes in marine fossils suggest that Jurassic global temperatures were generally quite warm. Geochemical evidence suggests that surface waters in the low latitudes were about 20 °C (68 °F), while deep waters were about 17 °C (63 °F). This greenhouse world created thermal currents and wind patterns that early fliers could exploit.

The global mean average temperatures were warmer than the present day by around 6–9 °C and the sea-level was generally also high. High sea levels meant extensive shallow seas and archipelagos – perfect landscapes for creatures learning to fly. Islands provided safe havens for experimental fliers, while the warm climate eliminated the energy costs of dealing with cold temperatures.

The geographical configuration of the Jurassic world also played a crucial role. During this period the supercontinent Pangea split apart, allowing for the eventual development of what are now the central Atlantic Ocean and the Gulf of Mexico. This breakup created new ecological niches and migration routes that flying creatures could exploit.

The Hollow Bone Revolution

One of the most ingenious adaptations that made Jurassic flight possible was the development of hollow bones. The development of hollow bones with air-filled cavities came early in the history of dinosaurs. Hollow bones might have first appeared as early as the Middle Triassic, around 245 million years ago in the last common ancestor of dinosaurs and pterosaurs.

This wasn’t just about weight reduction. They likely evolved to circulate more oxygen in the blood. This enabled sauropods to become large and keep cool in the warm climate. They also kept theropods light and nimble, which was ideal for hunting, fighting and, eventually, flying. The high oxygen content of Jurassic air made these hollow bone systems incredibly efficient, creating a biological foundation that supported both giant ground dinosaurs and flying pterosaurs.

The engineering of these bones was remarkably sophisticated. Like those of birds, the bones of pterosaurs are mostly hollow and filled with air, making what might otherwise be a hefty animal surprisingly light for its size. Quetzalcoatlus, for example, is estimated to have weighed up to 250 kilogrammes – incredibly light compared to giraffes, which can weigh more than 1,000 kilogrammes.

Dietary Diversity and Ecological Niches

The Jurassic Period saw an explosion of ecological opportunities that flying creatures could exploit. Diet varied by species. Some pterosaurs, such as Pterodaustro, had beaks with hundreds of fine needlelike teeth, which suggests that they were used for straining plankton. Other species, such as Cearadactylus, possessed larger teeth that splayed outward slightly, which was likely useful for capturing fish and land animals.

This dietary diversification reveals how flight opened up entirely new ways of life. Flying creatures could access food sources unavailable to ground-dwelling animals – from aerial insects to fish in remote lakes. Unlike most Jurassic pterosaurs, which thrived near marine environments, Melkamter lived far from the sea. The diet of this creature likely consisted of insects, while its marine counterparts fed on fish. This inland adaptation suggests pterodactyloids may have originated in such environments rather than along coastal regions.

The ability to exploit different food sources reduced competition and allowed multiple flying species to coexist. This ecological flexibility was crucial for the success of both pterosaurs and early birds during the Jurassic.

Evolutionary Arms Race in the Skies

The Jurassic Period witnessed the first aerial evolutionary arms race in Earth’s history. Pterosaurs were the only vertebrates with powered flight for about 80 million years. Then around 150 million years ago, in the Jurassic period, a second group of backboned animals started to take wing: feathered dinosaurs. This competition drove rapid innovation on both sides.

Not all of the dinosaurian close relatives of birds could fly. But those that could, flew in a range of different ways – suggesting early evolutionary experiments of flight, with birds being the most successful of those experiments, and persisting to the present. The diversity of flight solutions during this period was extraordinary, from the membrane wings of pterosaurs to the four-winged gliders like Microraptor.

This competitive environment forced rapid improvements in flight efficiency, maneuverability, and specialized adaptations. Each group pushed the boundaries of what was possible, leading to innovations that would define aerial life for millions of years to come.

The Legacy of Jurassic Innovation

The flight innovations that emerged during the Jurassic Period didn’t just disappear with the pterosaurs – they established fundamental principles that continue to influence flying creatures today. Birds inherit their bipedalism from theropods, explaining why they evolved flight using just their forelimbs, unlike bats or pterosaurs. This body plan, perfected during the Jurassic, became the template for all future bird evolution.

The period also established the importance of metabolic efficiency in flight. Flight is highly energetic. Birds use a great deal of energy to fly, and that, added to their relatively small size and endothermy, makes them great users of oxygen. The high-oxygen environment of the Jurassic allowed early fliers to develop these energy-intensive lifestyles, setting the stage for the incredible diversity of flying creatures we see today.

Even the extinction patterns from this period continue to influence modern ecosystems. Despite this shakeup in the aerial niche, pterosaurs continued to dominate among the medium to large fliers, particularly in open habitats. Birds were mainly restricted to vegetated areas where their small body size and agility were advantageous. Pterosaurs were thus able to maintain supremacy as the rulers of the open sky.

Conclusion: The Jurassic Sky Revolution

The Jurassic Period stands as the most crucial chapter in flight evolution not because it saw the first flying creatures, but because it created the perfect conditions for flight to truly flourish and diversify. The combination of oxygen-rich atmosphere, warm global climate, fragmented geography, and emerging ecological niches created an evolutionary laboratory unlike anything before or since.

This wasn’t just about individual species learning to fly – it was about flight becoming a fundamental life strategy that would reshape ecosystems for the next 150 million years. The pterosaurs that soared through Jurassic skies, the early birds that tentatively flapped among island archipelagos, and the countless intermediate forms that experimented with gliding and powered flight all contributed to a revolution that continues to this day. Every time you see a bird take flight, you’re witnessing the legacy of innovations that began in the oxygen-rich skies of the Jurassic Period.

Who would have thought that the key to understanding modern flight lay not in studying today’s birds, but in imagining a world where the very air itself was supercharged for the adventure of leaving the ground behind?