In the vast expanse of Western Australia’s Great Sandy Desert, a perfect circle sits carved into the red earth like nature’s own ancient amphitheater. This isn’t just any geological feature – this is where two dramatically different worlds of understanding collide in the most fascinating way possible. To the Aboriginal peoples of the region, Wolfe Creek Crater—known as Kandimalal—is steeped in powerful Dreamtime stories, often tied to rainbow serpents and spirits shaping the land. To scientists, however, it’s the scar left behind by a massive meteorite that slammed into Earth some 120,000 years ago. Measuring nearly a kilometer across, the crater is one of the world’s best-preserved impact sites. Together, these perspectives weave a narrative that is both cultural and cosmic, reminding us that the land holds stories written in both legend and stone.

The Sacred Circle in the Sand

Wolfe Creek Crater stands as a well-preserved meteorite impact crater in Western Australia, positioned on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert in the Kimberley. The crater averages about 875 metres in diameter, with walls rising 60 metres from rim to present crater floor. But here’s what makes your jaw drop – this is one of the best-preserved meteorite craters on Earth, and it’s so perfectly preserved that it looks like it could’ve been carved yesterday.

The ridge of the crater stands about 35 metres above the surrounding flat sand plain, with outer edges that slope at a gradual 15 degrees, while the much steeper inner walls fall away at about a 50 degree angle. Standing at the rim, you feel like you’re peering into a window that connects our planet directly to the cosmos.

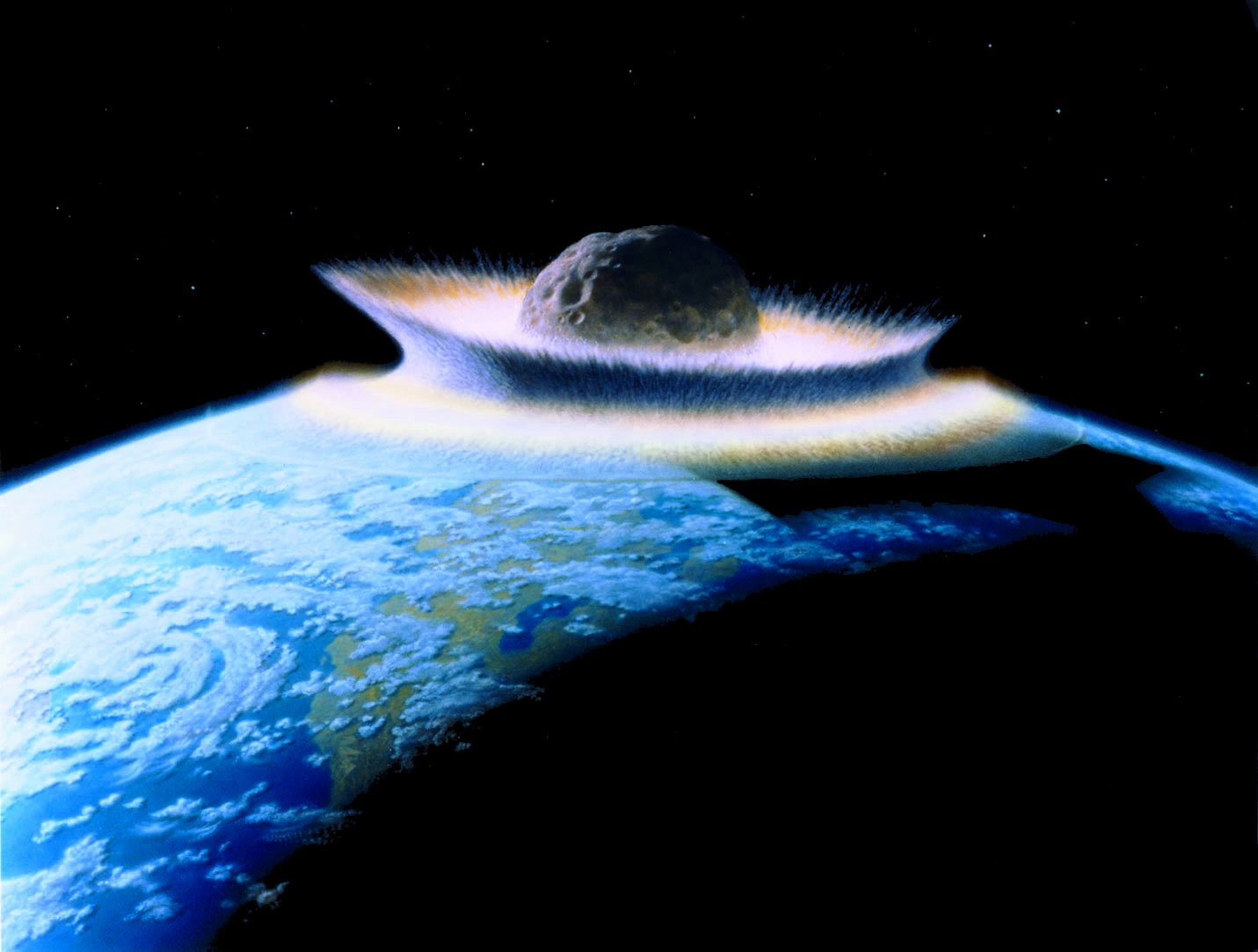

When Stars Fall to Earth

Scientists estimate that the meteorite that formed Wolfe Creek was about 15 metres in diameter and had a mass of about 14,000 tonnes. Imagine a building-sized chunk of iron and nickel hurtling through space and slamming into the Australian outback. The meteorite was probably travelling at 17 kilometres per second and struck with the force of 0.54 megatons of TNT.

For many years it was thought to have been created around 300,000 years ago, but in 2019, following investigations by researchers from Portsmouth University together with Australian and US researchers, it is now estimated to be less than 120,000 years old. This means that while our ancestors were developing complex tools and language, this cosmic catastrophe was reshaping the landscape.

The Aboriginal Dreamtime Connection

Long before any scientist set foot near this crater, the crater was known as Janyil in Jaru and as Karntimarlarl in Walmajarri. The crater is known as “Kandimalal” in the Djaru language, and here’s where things get truly remarkable.

Traditional Owners believe this circular crater was formed when a giant mythological snake raised its head from the ground back long ago at the time of creation. One well-known story refers to the passage of two rainbow snakes, which formed the nearby Wolfe Creek and Sturt Creek as they crossed the desert, with one snake emerging from the ground in the Dreamtime, forming the circular crater. The parallels between this ancient narrative and the scientific explanation are absolutely stunning.

The Star That Fell from Heaven

But the Aboriginal stories don’t stop there. In 1999, John Goldsmith recorded a story about a “star” that fell from the sky and became buried in the ground, forming the crater. According to Djaru Elder Jack Jugarie, one day, the crescent moon and the evening star passed very close to each other. The evening star became so hot that it fell to the ground, causing an enormous explosion, flash, dust cloud and noise. This frightened the people and a long time passed before they ventured near the crater to see what had happened.

Jack Jugarie indicated that this account was passed down from his grandfather’s grandfather, which suggests that the story originates from before the first contact with Europeans. This means Indigenous Australians were preserving scientific accuracy in their oral traditions for potentially thousands of years.

The Underground Mysteries

Another story relates to the sinkholes in the centre of the crater. One day, a Djaru man entered the crater and saw water in the sinkholes. He entered a sinkhole to discover a passage that went several kilometres underground to emerge at a nearby creek. After a considerable trek, he emerged into daylight. It is said that because of the link from the crater sinkholes and the creek, the crater floor never floods.

There are various versions of this story, generally the underground passage is said to emerge at Sturt Creek, but Wolfe Creek has also been indicated. Scientists today are fascinated by the geological accuracy embedded in these traditional narratives.

Cosmic Knowledge in the Kimberley

The depth of Aboriginal astronomical knowledge becomes even more impressive when you learn about “Coolungmurru” – Jack Jugarie’s description of a rare meteoric phenomenon that produces sound and vibration. Such events are known to occur when meteors cause sonic booms, and remarkably, this rare phenomenon is not only known, but was even given the name “Coolungmurru”.

The clear, dark skies of the Kimberley have enabled a remarkably intimate knowledge of cosmic events by some Djaru people. This isn’t just folklore – it’s sophisticated observational astronomy passed down through generations.

The European “Discovery”

Geologists F Reeves and D Hart were the first non-Aboriginal people to come across this striking natural feature while conducting an aerial survey of the Canning Basin in 1947. Australia’s Aboriginal people had long known about the crater near Wolfe Creek by the time an aerial survey identified it in 1947.

It was brought to the attention of scientists after being spotted during an aerial survey in 1947, investigated on the ground two months later, and reported in publication in 1949. What strikes you as fascinating is that while science was “discovering” this crater, Indigenous people had been incorporating its cosmic origins into their cultural knowledge for millennia.

A Natural Laboratory for Impact Science

The crater’s exceptional preservation allows for a clear and detailed view of the classic features created by a large meteorite strike, making it a textbook example of impact crater morphology. Its well-preserved structure clearly exhibits the characteristics of an impact crater, including a raised rim and a relatively flat floor, allowing scientists to study the processes that occur during and after a major impact event.

One of the most exciting discoveries at Wolfe Creek has been the presence of shatter cones and shocked minerals – geological signatures that can only be created under the extreme conditions of meteorite impact. These cone-shaped fractures in the rock look like nature’s own modern art installation, with radiating patterns that point back toward the center of impact. Scientists have also found microscopic diamonds and other high-pressure minerals that form only when normal rocks are subjected to pressures hundreds of thousands of times greater than atmospheric pressure.

The Hunt for Space Debris

Small numbers of iron meteorites have been found in the vicinity of the crater, as well as larger so-called ‘shale-balls’, rounded objects made of iron oxide, some weighing as much as 250 kilograms. Some of the rocks remaining in the crater now result from the meteorite itself. These rocks now take the form of rusted balls of iron-shale. Occurring in clusters, these balls can weigh as much as 250 kilograms apiece.

In 1963, Smithsonian Institution scientists visiting the crater identified two new minerals in the weathered meteoritic material, one of which they named “reevesite” in honor of Frank Reeves, one of the geologists who first documented the crater.

Recent Scientific Breakthroughs

Located in a remote part of Western Australia, on the edge of the Great Sandy Desert and about 145 kilometres from Halls Creek via the Tanami Road, Wolfe Creek Crater was formed by a meteorite estimated to be about 15 metres in diameter and weighing around 14,000 tonnes. The crater has an average diameter of approximately 875 metres, making it one of the most well-preserved impact craters globally. Scientists predict a depth of 178 metres and that it is filled by about 120 metres of sediment, mostly sand blown in from the desert.

A study by an international research team led by Professor Tim Barrows from the University of Wollongong has thrown new light on how frequently large meteorites strike the Earth. This research is helping scientists understand the cosmic bombardment patterns that have shaped our planet’s history.

Epilogue: Where Two Worlds Meet

What makes Wolfe Creek Crater truly extraordinary isn’t just its scientific significance or its cultural importance – it’s how these two ways of understanding the world complement each other so beautifully. Aboriginal Dreamtime stories preserved the memory of a cosmic impact with startling accuracy, while modern science provides the technical details that validate these ancient narratives.

This dual importance – both scientifically significant and culturally significant – adds layers to its appeal and importance. The rich cultural history adds another dimension to why the crater is important. Standing at the rim of this perfect circle in the desert, you’re witnessing something profound: the meeting point of 60,000 years of Indigenous knowledge and cutting-edge planetary science, both telling the same incredible story of the day the stars touched Earth.

Did you expect that ancient stories could be so scientifically accurate?