Picture this: you’re walking through an ancient forest seventy million years ago when suddenly, a massive spiked tail whips past your head at bone-crushing speed. Throughout dinosaur history, some of the most incredible evolutionary weapons weren’t teeth or claws – they were tails transformed into devastating defensive arsenals.

These prehistoric giants didn’t just carry their tails for balance. They weaponized them in ways that would make medieval knights jealous. From sledgehammer clubs that could shatter bones to razor-sharp spikes that punched through predator armor, dinosaur tails became some of nature’s most creative and brutal innovations. Let’s explore the eight dinosaurs whose tails packed the most devastating punch in prehistoric history.

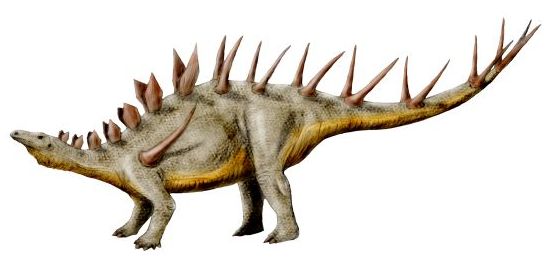

Stegosaurus: The Original Thagomizer Champion

The spiky tail of Stegosaurus, called a thagomizer, consists of four spikes arranged at the end of its tail. Fossil evidence confirms that the thagomizer was used to defend against massive carnivores like Allosaurus.

Many fossil Stegosaurus tail spikes show damage from combat, and paleontologists have found a punctured Allosaurus bone where a Stegosaurus tail spike fits perfectly. Unlike other dinosaurs, Stegosaurus had cartilage tendons in its tail instead of bone, making it flexible enough to swish from side to side while powerful forelimbs allowed quick pivoting for attacks.

Ankylosaurus: The Sledgehammer Specialist

Ankylosaurus had long, stiff tails with bony, hammer-like clubs. These tails measured up to 10 feet long with rows of sharp spikes along the sides, and the tip was fortified with bony structures creating a club that could swing with sledgehammer force.

Armored dinosaurs like ankylosaurs wielded sledgehammer-like tail clubs against other ankylosaurs in conflict, with fossil evidence showing healed injuries caused when another ankylosaur slammed its tail club into a dinosaur. Powerful tail muscles swung the tail from side to side, delivering bone-shattering blows to attackers.

Carnotaurus: The High-Speed Powerhouse

Carnotaurus had one ridiculously strong tail, with the largest caudofemoralis muscle of any known animal, living or extinct, for its size. Along its tail length were pairs of tall rib-like bones that interlocked with the next pair, supporting a huge caudofemoralis muscle.

When the tail moved, it gave momentum to the back legs, leading to remarkable strides that wouldn’t have been possible otherwise. Powered by an enormous tail muscle, Carnotaurus was the Usain Bolt of the Cretaceous, well-adapted for short-burst sprinting. Though the rigid tail structure made quick turns difficult, what Carnotaurus gave up in maneuverability, it made up for in straight-ahead speed.

Diplodocus: The Giant’s Whip

Heavy sauropods like Diplodocus could inflict stinging blows on attackers with their tapered, whip-like tails, which were made up of narrow, cylinder-shaped bones designed to lash out sharply. They could flick their whip-like tails with great force into predators’ bodies.

For these massive herbivores weighing several tons, their size alone deterred most predators. However, when threatened, their tails became precision weapons capable of delivering devastating strikes at incredible speeds. The long, flexible design allowed them to reach attackers positioned anywhere around their massive bodies, making escape nearly impossible for foolish predators.

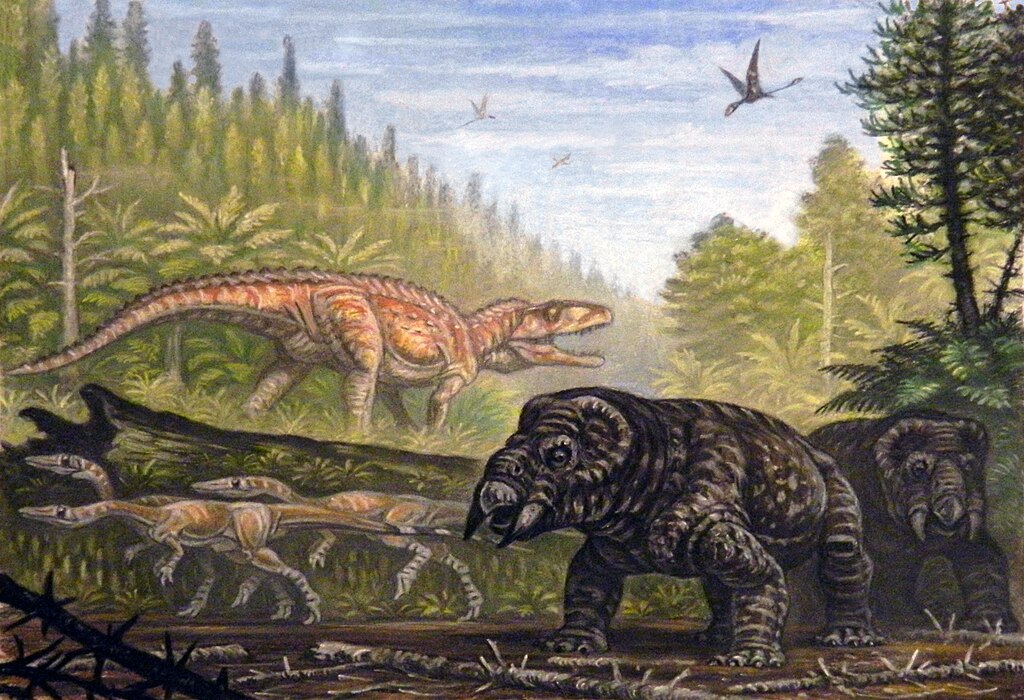

Kentrosaurus: The Spike-Swinging Specialist

Kentrosaurus, a smaller cousin of Stegosaurus found in Tanzania, was armed with a formidable array of paired spikes along its tail, and getting hit with such a tail would turn you into an instant shish kebab. According to paleontologist models, Kentrosaurus was a heavy hitter – the spikes at its tail tip could hit targets at over 40 meters per second.

Because its tail had at least forty vertebrae, it was highly mobile and could possibly swing at an arc of 180 degrees, with swing speeds reaching as high as 50 kilometers per hour. Continuous rapid swings allowed the spikes to slash open attacker skin or stab soft tissues and break ribs, while directed blows could fracture even sturdy leg bones through blunt trauma.

Zuul Crurivastator: The Shin Destroyer

The fossil belongs to Zuul crurivastator, whose name means “Zuul, the destroyer of shins,” given that its tail club was thought to be the enemy of tyrannosaurs and other upright predators. The back half of its tail was stiff with the tip encased in huge bony blobs, creating a formidable sledgehammer-like weapon.

Scientists know ankylosaurs could deliver very strong blows with their tail clubs, but most thought they fought predators – instead, ankylosaurs like Zuul may have been fighting each other. Scientists believe ankylosaurs used their weapon-like tails to assert social dominance, establish territory, or battle for mates, similar to how deer and antelope use antlers today.

Stegouros Elengassen: The Aztec War Club

The end of Stegouros elengassen’s tail was unlike anything scientists have seen before: a mass of fused bone resembling a jagged cricket bat. With its flat surface and sharp blades along the sides, this unique structure strongly resembles an Aztec war club called a macuahuitl.

The anatomical structure was named the macuahuitl by researchers, after the obsidian-bladed wooden club wielded by the Aztec. Stegouros elengassen’s strange tail is unique among dinosaur weapons, representing an entirely unprecedented evolutionary adaptation that lived between seventy-two and seventy-five million years ago.

Therizinosaurus: The Scythe Bearer

Therizinosaurus’s most distinctive feature was its long, scythe-like claws, which could reach lengths of up to 3.3 feet and are among the longest of any known animal. These claws are thought to be the longest of any land animal ever.

While not technically a tail weapon, Therizinosaurus moved on two legs and its tail served as a counterbalance to its heavy front body. The fearsome claws would have certainly deterred giant predators such as Tarbosaurus from attacking. Though we don’t know if the huge claws were strong enough as weapons against other dinosaurs, they might have been mostly useful as threat displays to make creatures think twice before attacking.

Conclusion

These eight dinosaur species prove that evolution doesn’t just create survivors – it creates innovators. Each tail represented millions of years of natural engineering, turning what started as simple balance aids into sophisticated weapons systems. From the precision strikes of Stegosaurus to the devastating clubs of ankylosaurs, these prehistoric powerhouses wielded their tails with deadly efficiency.

The next time you see a lizard casually flick its tail, remember its ancient relatives who transformed this appendage into nature’s most creative weapons. These dinosaurs didn’t just rule through size or teeth – they dominated through pure tail power. What do you think about these incredible prehistoric weapons? Tell us in the comments.