Imagine stepping back in time to a world where dragonflies had wingspans wider than a hawk’s, where millipedes stretched longer than a king-size bed, and where scorpions grew to the size of modern-day wolves. This wasn’t some fantasy realm from a horror movie – this was Earth roughly 300 million years ago, during the Carboniferous Period. Long before the first dinosaur ever roamed the planet, our world was dominated by arthropods so massive they would make today’s largest insects look like toys.

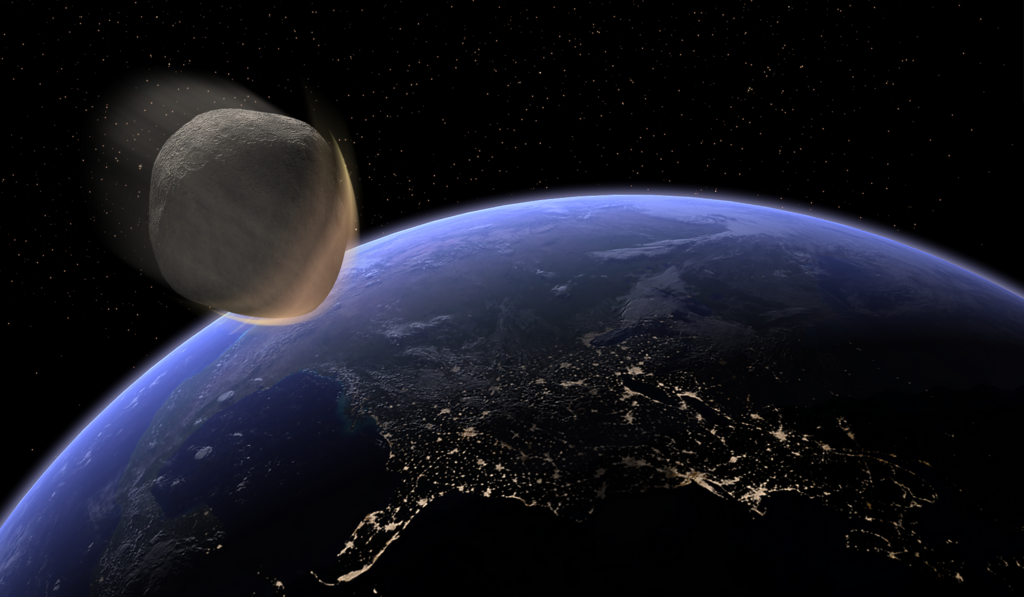

The secret behind these colossal creatures wasn’t magic or mutation – it was oxygen. During the Carboniferous Period, atmospheric oxygen levels soared to nearly 35%, compared to today’s 21%. This oxygen-rich environment allowed insects and other arthropods to grow to absolutely staggering proportions, creating a landscape that would seem alien to modern eyes.

The Oxygen Revolution That Created Giants

The Carboniferous Period marked one of the most dramatic atmospheric changes in Earth’s history. Massive forests of primitive trees pumped unprecedented amounts of oxygen into the atmosphere while simultaneously removing carbon dioxide. This created a perfect storm for arthropod gigantism.

Unlike mammals, insects don’t have lungs or circulatory systems to transport oxygen throughout their bodies. Instead, they rely on a network of tubes called tracheae that deliver oxygen directly to their tissues. With more oxygen available, these primitive breathing systems could support much larger body sizes. The result was a world where nightmares became reality – at least from a modern perspective.

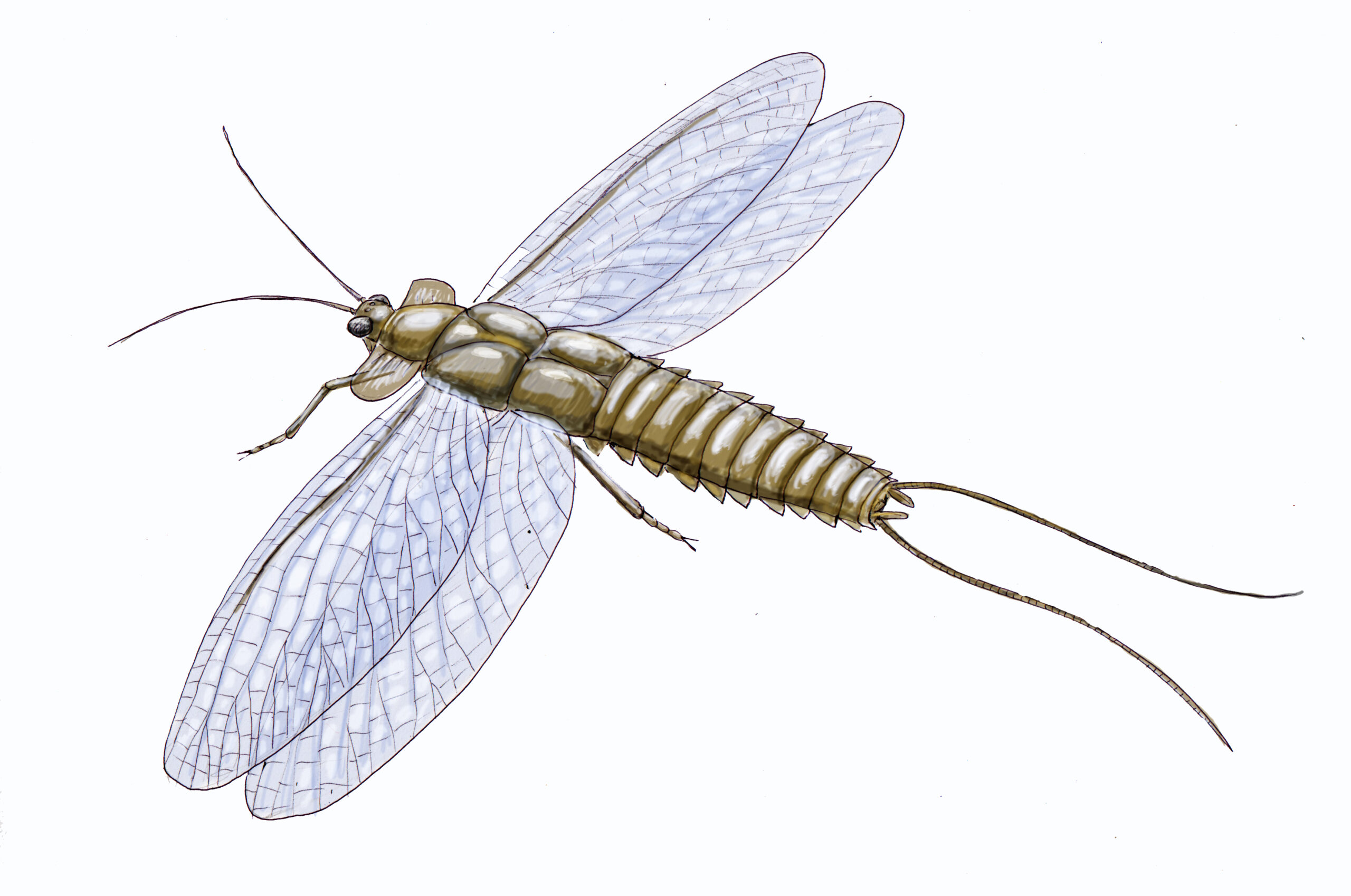

Meganeura: The Flying Terror With Wings of Steel

Picture a dragonfly with a wingspan stretching nearly three feet across, and you’ve got Meganeura, perhaps the most famous giant insect of the Carboniferous. These aerial predators dominated the skies with wings that spanned up to 28 inches, making them roughly the size of a modern seagull. Their massive compound eyes contained thousands of individual lenses, giving them incredibly sharp vision for hunting.

Meganeura was built for speed and precision. Its powerful flight muscles could propel it through the air at remarkable speeds, while its serrated mandibles could slice through prey with surgical precision. These weren’t gentle giants – they were apex predators that ruled the ancient skies with the same authority that eagles command today.

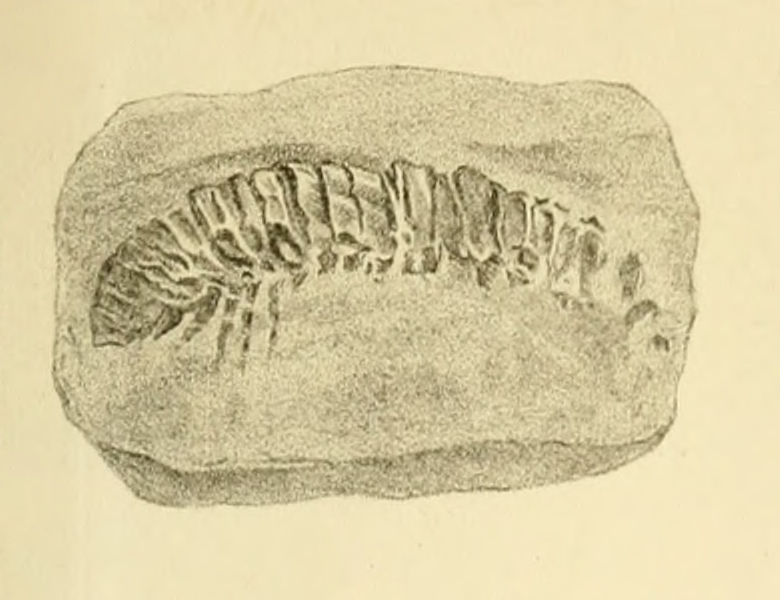

Arthropleura: The Giant Millipede That Dwarfed Modern Snakes

Walking through a Carboniferous forest, you might have encountered something that looked like a living subway car crawling across the forest floor. Arthropleura reached lengths of up to 8.5 feet and weighed as much as a large dog. These colossal millipedes were the largest land arthropods that ever lived, making today’s biggest millipedes look like earthworms by comparison.

Despite their intimidating size, these giants were actually herbivores, feeding on the abundant plant matter of their time. Their segmented bodies were protected by thick, armor-like plates, and they moved with surprising grace for such massive creatures. Finding a complete Arthropleura fossil is incredibly rare, making these ancient giants some of the most sought-after specimens in paleontology.

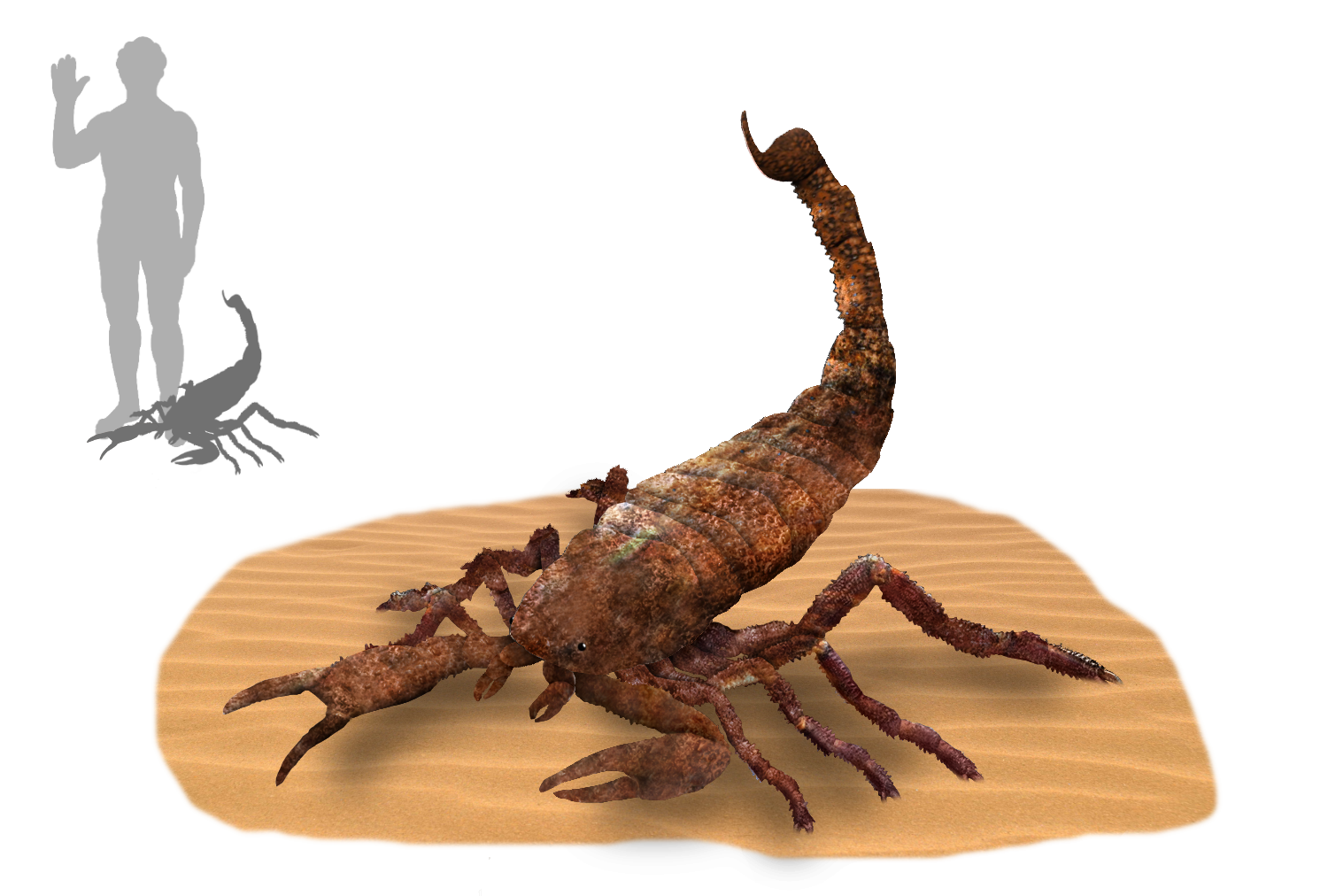

Pulmonoscorpius: The Scorpion That Could Hunt Small Sharks

In the warm, shallow seas of the Carboniferous, a predator lurked that would make modern scorpions seem like harmless toys. Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis stretched over three feet in length, with massive pincers capable of crushing prey with bone-breaking force. These aquatic scorpions were perfectly adapted for underwater hunting, with specialized gills that allowed them to breathe beneath the waves.

What made Pulmonoscorpius truly terrifying wasn’t just its size, but its hunting strategy. These ancient arachnids were ambush predators that could remain motionless for hours before striking with lightning speed. Their powerful tail, armed with a venomous stinger, could deliver a lethal dose of toxin to prey much larger than themselves.

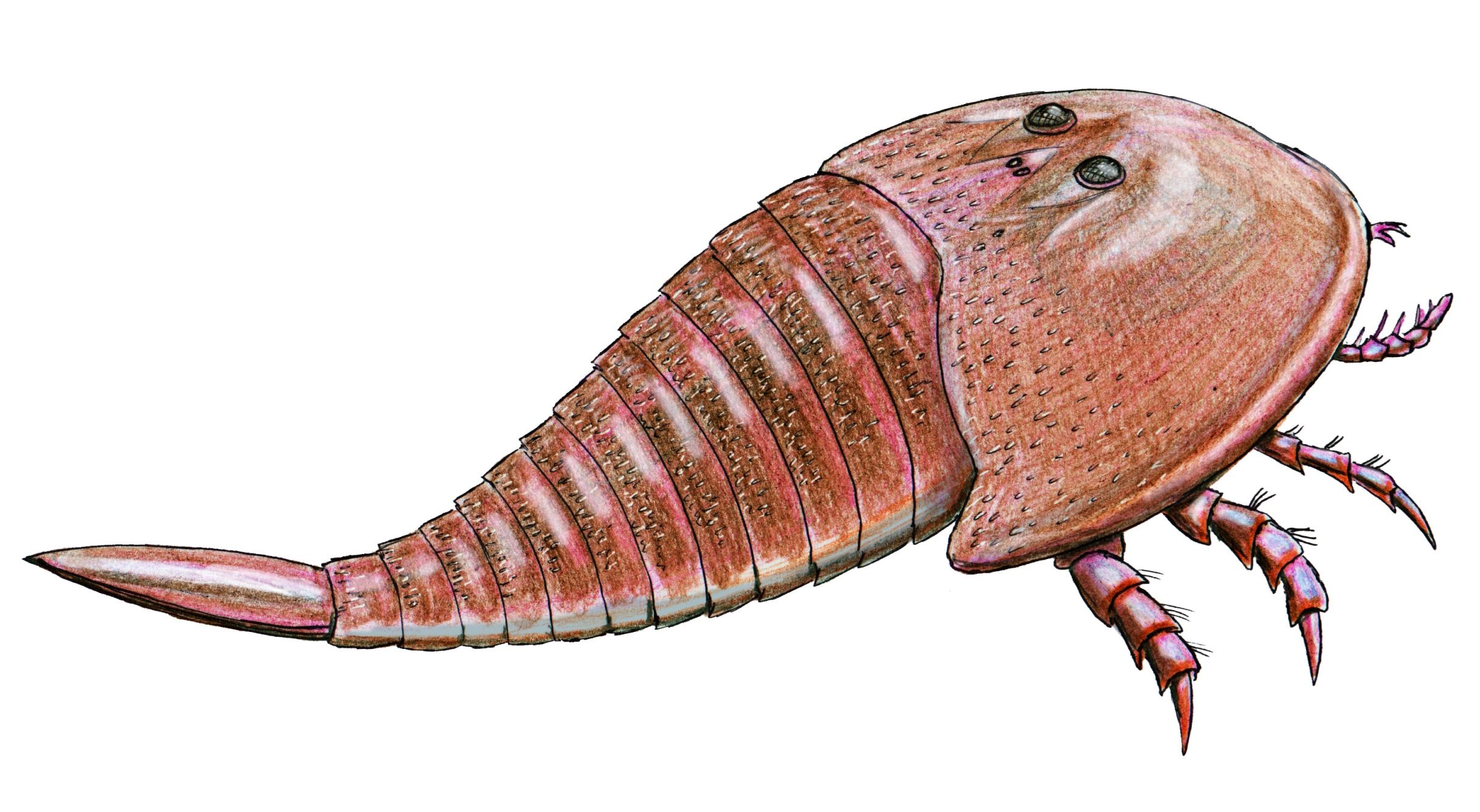

Mazothairos: The Enormous Sea Scorpion That Ruled Ancient Oceans

Before Pulmonoscorpius, an even more massive predator dominated the ancient seas. Mazothairos enormis lived up to its name, reaching lengths of nearly 5.5 feet and possessing claws that could easily grasp a human torso. These sea scorpions, known as eurypterids, were the apex predators of their time, feared by fish, trilobites, and other marine life.

The sheer power of Mazothairos was legendary. Fossil evidence suggests these creatures could generate crushing forces comparable to modern crocodiles. Their paddle-like appendages made them surprisingly agile swimmers, allowing them to chase down prey with ruthless efficiency. When these giants went extinct, they left behind a void in marine ecosystems that wouldn’t be filled until the rise of large sharks millions of years later.

Jaekelopterus: The Ultimate Prehistoric Predator

If Mazothairos was impressive, then Jaekelopterus rhenaniae was absolutely mind-blowing. This colossal sea scorpion reached lengths of up to 8.2 feet, making it one of the largest arthropods ever discovered. Its massive claws, some measuring over 18 inches long, could have easily torn apart prey the size of small whales.

Jaekelopterus lived during the Devonian Period, roughly 390 million years ago, and represented the pinnacle of arthropod evolution. These creatures were so perfectly adapted for predation that they dominated marine ecosystems for millions of years. Their extinction marked the end of an era when arthropods, not vertebrates, ruled the seas.

Titanoptera: The Massive Stick Insects That Weren’t Insects

https://doi.org/10.3853/j.1835-4211.40.2024.1902, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=164510940)

Among the strangest giants of the Carboniferous were the Titanoptera, creatures that looked like enormous stick insects but were actually more closely related to modern grasshoppers and crickets. These peculiar arthropods could reach lengths of over 16 inches, with incredibly long, thin legs that gave them an almost otherworldly appearance.

What made Titanoptera truly unique was their lifestyle. Unlike most of their contemporaries, these creatures were likely omnivorous, feeding on both plant matter and smaller arthropods. Their unusual body structure suggests they were skilled climbers, capable of navigating the complex three-dimensional environment of Carboniferous forests with remarkable agility.

Meganisoptera: The Dragonfly Dynasty That Dominated Ancient Skies

While Meganeura gets most of the attention, it was actually part of a larger group called Meganisoptera that included several species of giant dragonflies. These aerial hunters came in various sizes, from merely large to absolutely gigantic, and they dominated the skies for millions of years.

The diversity within Meganisoptera was remarkable. Some species specialized in hunting over water, while others preferred forest environments. Their wing patterns varied dramatically, suggesting different flight strategies and hunting techniques. These ancient dragonflies were so successful that they occupied nearly every aerial niche available, from high-altitude cruising to ground-level ambush hunting.

Hibbertopterus: The Armored Giant That Bridged Sea and Land

Hibbertopterus scouleri represents one of the most fascinating transitions in arthropod evolution. This massive eurypterid, measuring up to 5.2 feet in length, was among the first large arthropods to venture onto land. Its thick, armored exoskeleton provided protection both in water and on primitive beaches.

What makes Hibbertopterus particularly interesting is its potential role in arthropod evolution. Some scientists believe these creatures may have been among the first large predators to exploit coastal environments, paving the way for the land-dwelling giants that would follow. Their fossils provide crucial insights into how aquatic arthropods made the transition to terrestrial life.

Brontoscorpio: The Pioneer Land Scorpion

While most giant arthropods of the Carboniferous were aquatic, Brontoscorpio anglicus was among the first large arachnids to make land its permanent home. Measuring nearly three feet in length, this ancient scorpion was perfectly adapted for terrestrial hunting, with powerful legs for rapid movement across primitive landscapes.

Brontoscorpio’s significance extends beyond its impressive size. This creature represents a crucial evolutionary step in the colonization of land by arthropods. Its specialized breathing apparatus and moisture-retention adaptations became the template for all future terrestrial arachnids. Without pioneers like Brontoscorpio, the rich diversity of land-dwelling arthropods we see today might never have evolved.

Kampecaris: The Millipede That Started It All

Long before Arthropleura dominated Carboniferous forests, a much smaller but equally important creature was making its mark on land. Kampecaris obanensis, measuring just over an inch in length, was one of the earliest millipedes to leave the safety of aquatic environments. While not gigantic by Carboniferous standards, this tiny pioneer laid the groundwork for the massive land arthropods that would follow.

Kampecaris is significant because it represents the very beginning of terrestrial arthropod evolution. Its fossilized remains, found in 425-million-year-old rocks, show clear adaptations for life on land. This humble millipede’s descendants would eventually grow to enormous proportions, proving that even the smallest pioneers can lead to the most dramatic evolutionary changes.

The Mysterious Extinction: Why Giants Disappeared

The end of the Carboniferous Period marked a dramatic shift in Earth’s atmosphere and climate. As oxygen levels dropped and carbon dioxide increased, the giants that had ruled for millions of years began to disappear. The same atmospheric changes that had created these monsters now spelled their doom.

Climate change, habitat loss, and increased competition from emerging vertebrates all played roles in their extinction. The rise of early reptiles and amphibians created new predators that were better adapted to changing conditions. Within a few million years, the age of giant arthropods was over, leaving behind only fossils and the smaller descendants we see today.

Living Echoes: How Modern Insects Compare

Today’s largest insects pale in comparison to their Carboniferous ancestors. The biggest modern dragonflies have wingspans of just 7.5 inches, while the largest millipedes reach only about 15 inches in length. This dramatic size reduction reflects the fundamental constraints of lower oxygen levels and increased competition in modern ecosystems.

However, some modern arthropods still hint at their giant heritage. Japanese spider crabs can reach leg spans of 12 feet, while certain deep-sea isopods grow to impressive sizes in the oxygen-rich depths. These living giants remind us that under the right conditions, arthropods can still achieve remarkable proportions.

Conclusion: Lessons From the Age of Giants

The story of Carboniferous giants offers profound insights into how environmental conditions shape evolution. These massive arthropods weren’t just biological curiosities – they were perfectly adapted products of their time, shaped by atmospheric conditions that will never exist again on Earth.

Their legacy lives on in every modern insect, spider, and millipede we encounter today. While today’s arthropods may be smaller, they carry within their genes the potential for greatness that once produced giants. The next time you see a dragonfly hovering over a pond or watch a millipede curl into a protective ball, remember that you’re looking at descendants of creatures that once ruled the world.

These ancient giants remind us that life finds a way to exploit every available niche, no matter how extreme the conditions. In a world facing rapid environmental change, the story of Carboniferous arthropods serves as both inspiration and warning about the power of atmospheric chemistry to reshape the very foundations of life on Earth.

What other secrets might these ancient giants hold about the relationship between environment and evolution?