Imagine walking through a prehistoric landscape where massive dinosaur carcasses lay scattered across ancient plains, their bones bleached white under a relentless sun. But these skeletal remains weren’t destined to become fossils just yet. Instead, they became a feast for some of nature’s most determined scavengers—creatures whose powerful jaws and specialized digestive systems could crack through bone like we crack nuts today. These bone-crushing specialists played a crucial role in prehistoric ecosystems, cleaning up after the giants and recycling nutrients back into the food web.

The Mighty Hyaenodon: Terror of the Tertiary

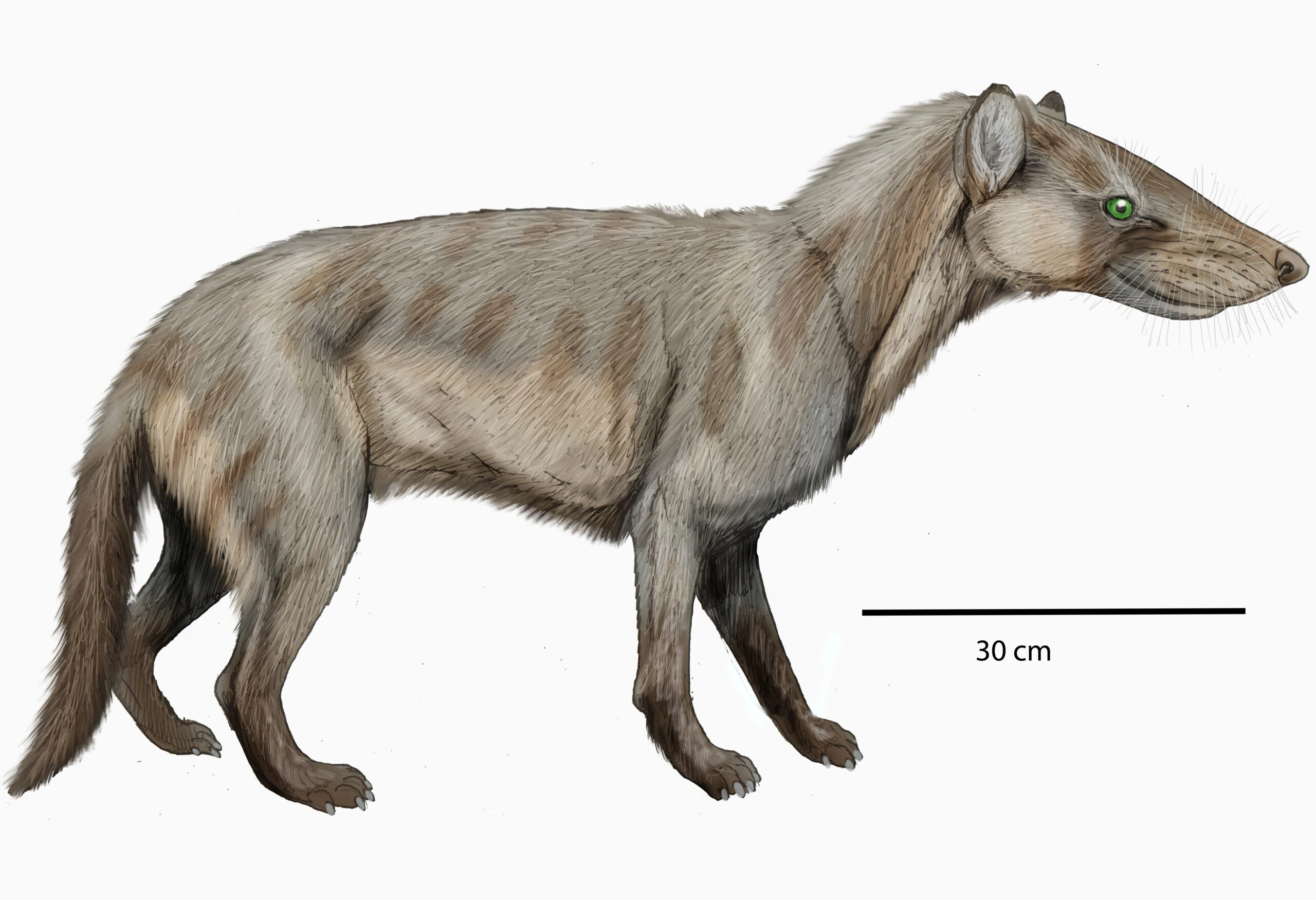

Long after the dinosaurs vanished, Hyaenodon emerged as one of the most formidable bone-crackers of its time. This wolf-sized predator possessed jaws that could generate crushing forces comparable to modern hyenas, making short work of any fossilized dinosaur bones it encountered. Living roughly 40 million years ago, Hyaenodon had specialized carnassial teeth that worked like scissors, slicing through tough connective tissue and bone marrow with ruthless efficiency. Unlike modern mammals, this ancient hunter had a much longer skull and more powerful jaw muscles, allowing it to process bones that would challenge even today’s most dedicated scavengers. Picture this beast stumbling upon a weathered T-rex femur and methodically working its way through the dense bone structure, extracting every last bit of nutritious marrow hidden within.

Deinonychus: The Raptor with Bone-Breaking Habits

While Deinonychus is famous for its sickle-shaped claws and pack-hunting behavior, recent studies suggest these intelligent predators also had a taste for bone. Their razor-sharp teeth weren’t just designed for slicing flesh—they could puncture and crack bones to access the nutrient-rich marrow inside. When a Deinonychus pack brought down a large herbivore, they didn’t waste anything, systematically breaking bones to extract every possible calorie. These raptors had incredibly strong jaw muscles relative to their body size, giving them the power to crunch through smaller bones entirely. Think of them as the prehistoric equivalent of a Swiss Army knife—equipped for multiple feeding strategies depending on what the hunt provided.

Carnotaurus: The Horned Devil with a Bone-Crushing Bite

Carnotaurus wasn’t just a fearsome hunter—it was also an opportunistic scavenger with jaws built for demolition work. This South American theropod had a skull designed like a battering ram, with incredibly robust jaw muscles that could exert tremendous pressure. When fresh prey was scarce, Carnotaurus likely turned to scavenging, using its powerful bite to crack open the bones of dead dinosaurs and extract the marrow within. Its teeth were blade-like and deeply rooted, perfect for both slicing flesh and applying the kind of sustained pressure needed to break through thick bone. Scientists believe that like modern Komodo dragons, Carnotaurus could dislocate its jaw joints to accommodate larger chunks of bone and flesh.

Allosaurus: The Lion of the Jurassic

Allosaurus operated much like a modern big cat, combining active hunting with opportunistic scavenging whenever the chance arose. This apex predator had serrated teeth that worked like steak knives, but its jaw structure also allowed for the kind of sustained pressure needed to crack bones. When Allosaurus encountered a dinosaur carcass—whether from its own kill or someone else’s—it would systematically work through the remains, breaking bones to access the nutritious marrow inside. Fossil evidence shows distinctive bite marks on dinosaur bones that match Allosaurus tooth patterns, suggesting these predators regularly fed on skeletal remains. Their feeding behavior probably resembled that of African lions, who also crush bones to extract every available nutrient from their prey.

Tyrannosaurus Rex: The Ultimate Bone-Crushing Machine

T-rex possessed arguably the most powerful bite force of any land animal that ever lived, with estimates reaching up to 60,000 pounds per square inch—enough to crush a car. This incredible jaw strength wasn’t just for show; it allowed T-rex to pulverize the bones of its prey completely, digesting even the largest femurs and vertebrae. Unlike many other theropods, T-rex had robust, conical teeth that were perfect for crushing rather than just slicing, indicating a feeding strategy that included serious bone consumption. Coprolite evidence (fossilized feces) from T-rex contains bone fragments, proving these giants regularly consumed and digested skeletal material. When a T-rex finished with a carcass, very little would remain—bones, marrow, and all would disappear into that massive digestive system.

Giganotosaurus: The South American Bone-Breaker

Even larger than T-rex, Giganotosaurus roamed South America with jaws capable of incredible destruction. This massive predator had a skull over six feet long, filled with razor-sharp teeth designed for both cutting and crushing. When Giganotosaurus scavenged dinosaur remains, it could easily crack through the largest bones, accessing marrow that smaller predators couldn’t reach. Its feeding strategy likely involved both active predation and opportunistic scavenging, with those enormous jaws making quick work of any skeletal remains it encountered. The sheer size of this predator meant it needed enormous amounts of nutrition, making bone consumption not just possible but necessary for survival. Archaeological evidence suggests Giganotosaurus could process bones from even the largest sauropods, turning massive leg bones into digestible fragments.

Mapusaurus: The Pack-Hunting Bone-Crusher

What made Mapusaurus particularly dangerous wasn’t just its individual size, but its suspected pack-hunting behavior combined with bone-crushing capabilities. These massive predators worked together to bring down enormous sauropods, then cooperatively fed on the remains—bones and all. A group of Mapusaurus could systematically strip a carcass, with different individuals focusing on different parts of the skeleton to maximize nutritional extraction. Their teeth showed adaptations for both slicing flesh and applying crushing pressure to bones, making them incredibly efficient at processing entire carcasses. When multiple Mapusaurus worked together on a kill, they could crack through even the most massive dinosaur bones, ensuring nothing edible went to waste. This cooperative bone-processing behavior would have made them one of the most efficient scavenging forces in prehistoric ecosystems.

Carcharodontosaurus: The African Shark-Tooth Giant

Named for its shark-like teeth, Carcharodontosaurus was perfectly equipped for both hunting and bone consumption in prehistoric Africa. Its massive skull housed teeth that could slice through flesh and then pivot to apply crushing pressure to bones, much like a modern crocodile’s feeding technique. This versatile predator could adapt its feeding strategy based on available resources, switching from active hunting to intensive scavenging when opportunities arose. The robust construction of its skull and jaw muscles suggests Carcharodontosaurus regularly consumed bones as part of its diet, not just as an occasional supplement. Fossil evidence indicates these predators left distinctive bite marks on dinosaur bones, showing they routinely fed on skeletal remains. Their feeding behavior probably involved holding bones steady with their powerful arms while applying maximum jaw pressure to crack through even the toughest skeletal material.

Spinosaurus: The Semi-Aquatic Scavenger

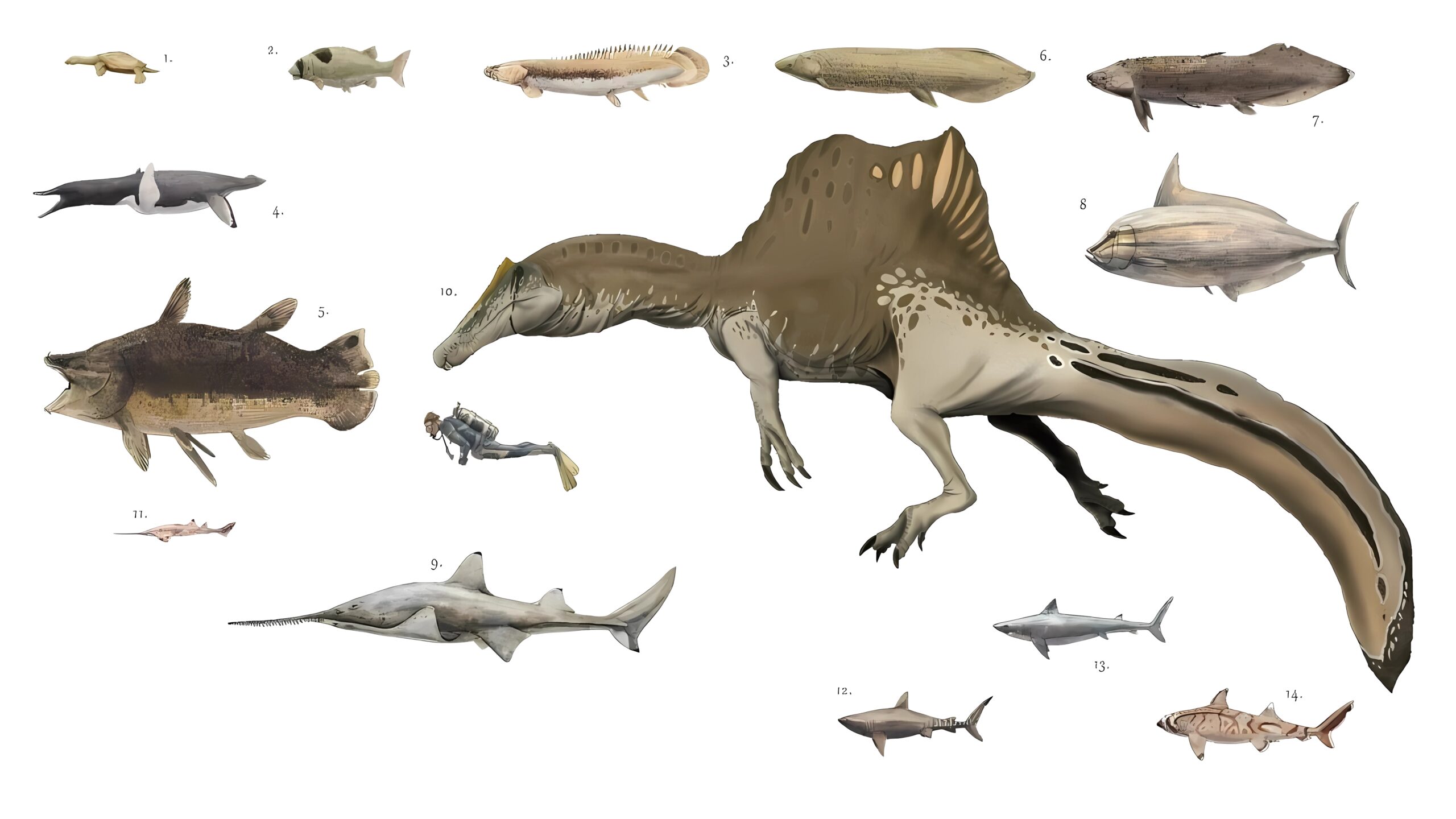

While famous for its fish-eating habits, Spinosaurus was also an opportunistic scavenger that likely consumed dinosaur bones when available. Its elongated skull and conical teeth were primarily adapted for catching fish, but the robust construction of its jaws suggests it could also process bones when necessary. Living in river systems, Spinosaurus would have encountered the remains of land dinosaurs that died near water or were washed downstream during floods. Its semi-aquatic lifestyle gave it access to carcasses that other predators might miss, including bones that had been softened by water exposure. The nutrient-dense marrow in these bones would have provided valuable calories to supplement its primarily piscivorous diet, especially during seasons when fish were less abundant.

Acrocanthosaurus: The High-Spined Hunter

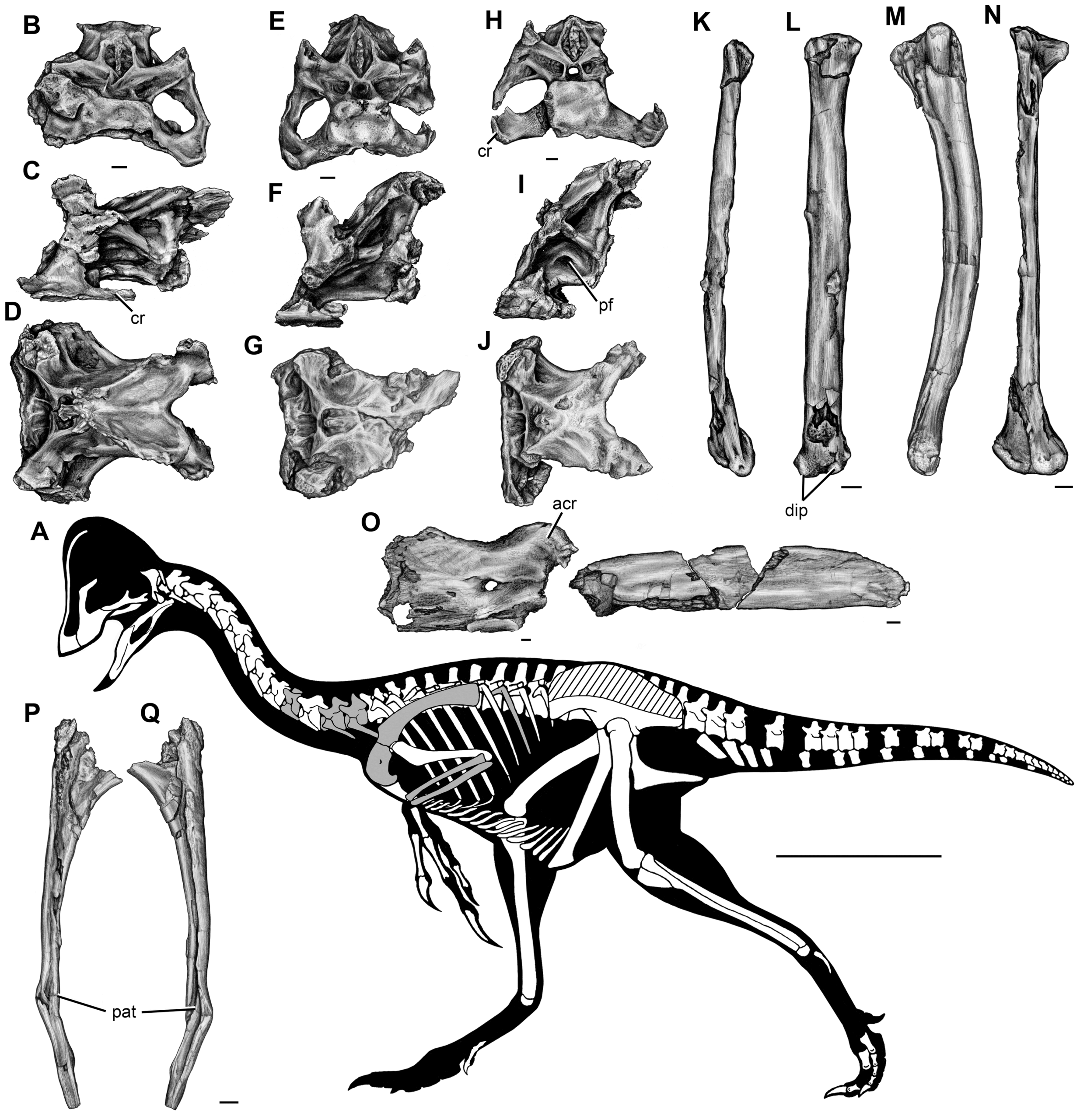

Acrocanthosaurus combined impressive size with specialized adaptations that made it an efficient bone-processor. Its distinctive neural spines weren’t just for display—they anchored massive neck and back muscles that gave this predator incredible bite force. When Acrocanthosaurus encountered dinosaur carcasses, it could use this enhanced musculature to crack through substantial bones, accessing marrow and nutrients that other scavengers couldn’t reach. The structure of its teeth shows adaptations for both cutting and crushing, indicating a flexible feeding strategy that included regular bone consumption. This North American predator likely spent considerable time scavenging, using its powerful jaws to process the skeletal remains of everything from small ornithopods to massive sauropods. Its feeding efficiency would have made it a dominant force in cleaning up prehistoric carcasses.

Tarbosaurus: Asia’s Bone-Crushing Tyrant

As Asia’s answer to T-rex, Tarbosaurus possessed similarly devastating bite force and bone-crushing capabilities. This massive predator had a slightly more elongated skull than its North American cousin, but maintained the same robust teeth and jaw muscles necessary for processing bones. Living in the diverse ecosystems of ancient Mongolia and China, Tarbosaurus encountered a wide variety of dinosaur species, from duck-billed hadrosaurs to armored ankylosaurs. Its feeding strategy included systematic bone consumption, breaking down skeletal remains to access every possible nutrient. Coprolite evidence suggests Tarbosaurus regularly consumed and digested bone material, indicating this behavior was a crucial part of its survival strategy. The abundance of prey species in its environment meant plenty of opportunities for both fresh kills and scavenged remains, all of which would be processed down to the smallest bone fragments.

Albertosaurus: The Efficient Pack Scavenger

Smaller than T-rex but no less effective, Albertosaurus combined pack behavior with impressive bone-crushing abilities. These predators worked together to process large carcasses, with different individuals focusing on different parts of the skeleton to maximize efficiency. Their slightly more gracile build compared to T-rex didn’t diminish their bone-processing capabilities—if anything, it made them more versatile in accessing different parts of a carcass. Albertosaurus had the perfect combination of cutting and crushing teeth, allowing them to slice through flesh and then switch to bone-breaking mode when needed. Fossil bone beds containing multiple Albertosaurus individuals suggest these predators regularly gathered at large carcasses, working cooperatively to extract every possible calorie. Their pack scavenging behavior would have made them incredibly effective at cleaning up dinosaur remains, leaving very little for other scavengers to claim.

Conclusion

The prehistoric world was a harsh place where nothing went to waste, and these remarkable bone-crushing specialists played essential roles in their ecosystems. From the pack-hunting Albertosaurus to the mighty T-rex, each of these ancient predators had evolved unique adaptations for extracting maximum nutrition from dinosaur carcasses. Their bone-crushing abilities weren’t just about survival—they were crucial recycling systems that kept nutrients flowing through prehistoric food webs. These powerful jaws could crack through the toughest skeletal remains, accessing marrow and minerals that would otherwise be locked away in bone. What’s most fascinating is how these diverse predators all independently evolved similar solutions to the same challenge: how to get the most nutrition possible from every kill or discovered carcass. Did you ever imagine that some of our planet’s most fearsome predators spent as much time crunching bones as they did hunting live prey?