In the prehistoric world, long before humans dominated the Earth, ancient relatives of today’s armadillos roamed the Americas’ landscapes as formidable armored tanks. These weren’t the small, cat-sized creatures we know today, but massive beasts that could potentially crush modern vehicles under their weight. Known as glyptodonts, these prehistoric mammals represented one of nature’s most impressive examples of gigantism, equipped with dome-shaped shells and club-like tails that made them living fortresses. Their imposing size and extraordinary adaptations have fascinated paleontologists for generations, offering glimpses into Earth’s distant past when megafauna ruled supreme.

The Evolutionary Origins of Giant Armadillos

Giant armadillos, also known as glyptodonts, belong to the superorder Xenarthra, which includes modern sloths, anteaters, and armadillos. These prehistoric behemoths evolved from smaller armadillo-like ancestors during the Miocene epoch, roughly 20 million years ago. Their evolutionary journey took place primarily in South America, which existed as an island continent for much of the Cenozoic era, allowing for unique evolutionary adaptations without competition from other large mammalian predators. This isolation created the perfect laboratory for armadillo relatives to grow to extraordinary sizes through a process known as island gigantism. By the time they reached their peak during the Pleistocene epoch (2.6 million to 11,700 years ago), these animals had diverged dramatically from their smaller cousins, developing specialized traits that would make them among the most heavily armored land animals ever to exist.

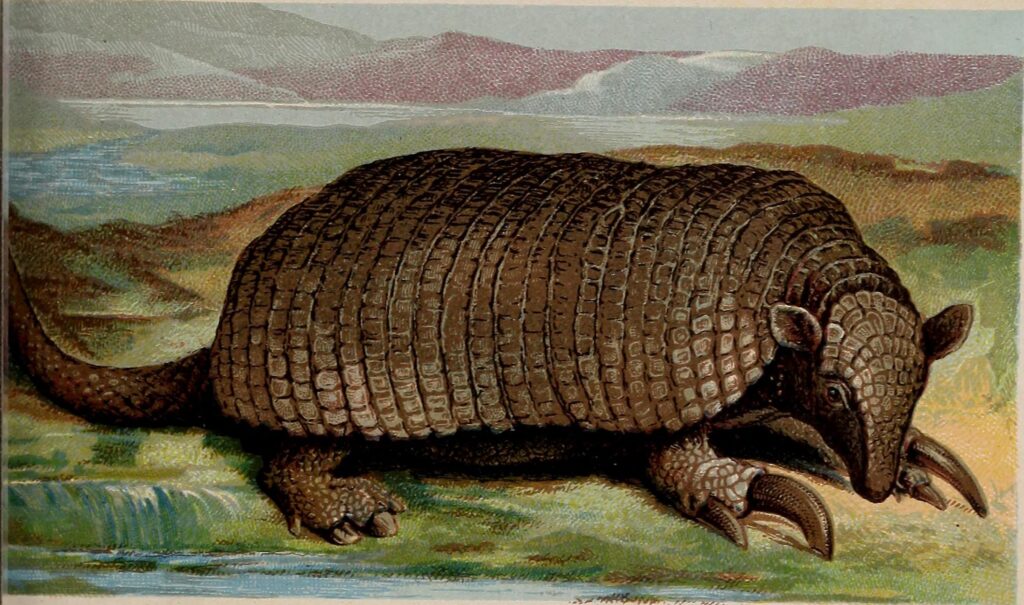

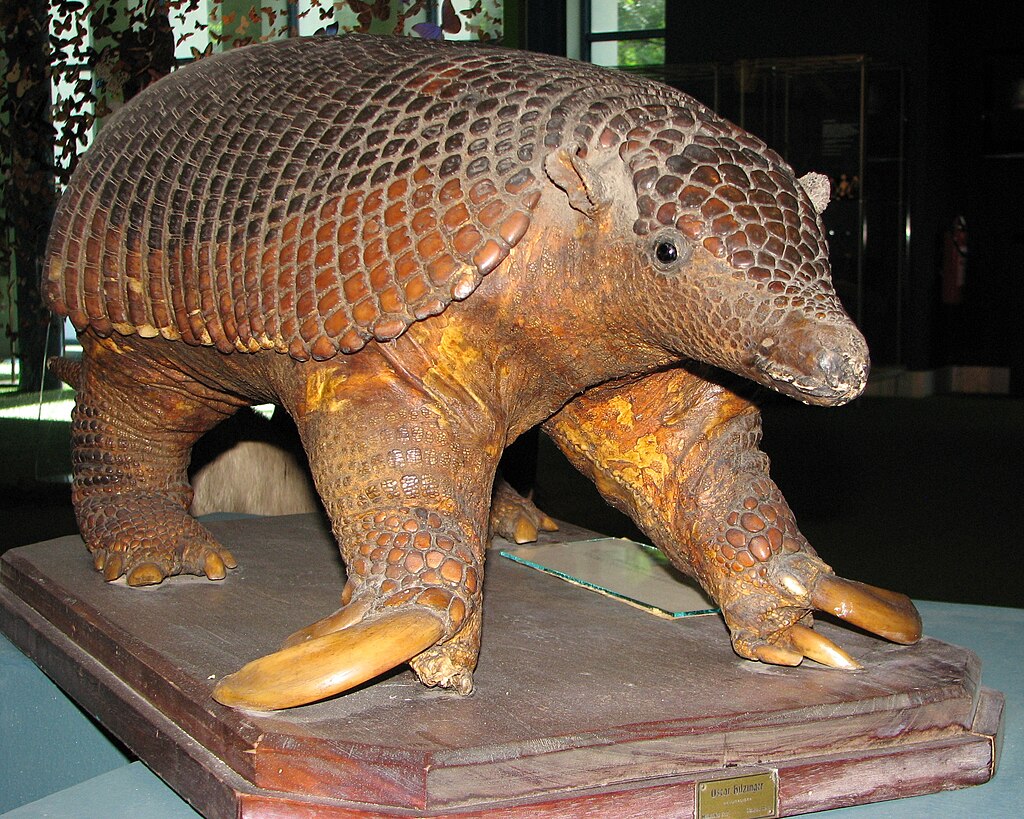

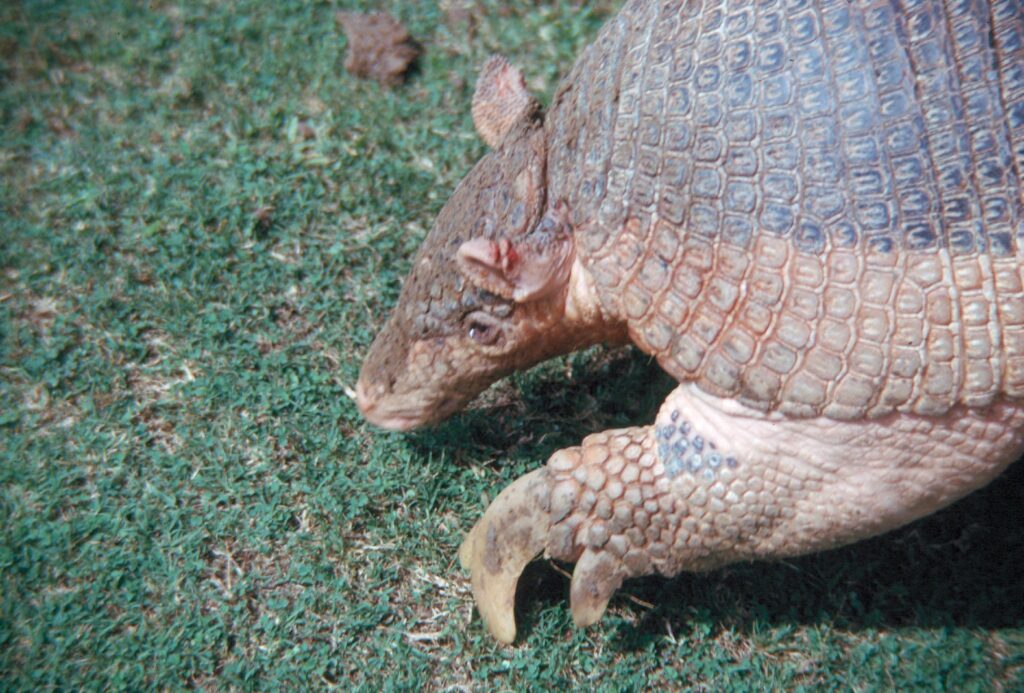

Astonishing Size and Weight Proportions

The most striking feature of glyptodonts was their sheer mass. The largest species, Doedicurus clavicaudatus, could reach lengths of approximately 13 feet (4 meters) and weigh up to 4,400 pounds (2,000 kilograms) – roughly the weight of a modern SUV. Their massive size would indeed have made them capable of crushing smaller vehicles had they coexisted with human technology. For comparison, today’s largest armadillo species, the giant armadillo (Priodontes maximus), typically weighs only about 70 pounds (32 kilograms) and reaches lengths of around 5 feet (1.5 meters) including the tail. This enormous difference in scale demonstrates the remarkable evolutionary path these creatures followed, developing from relatively modest-sized mammals into colossal armored giants that dominated their ecological niches across the Americas. Their weight was distributed across a broad, low-slung body supported by thick, column-like legs that evolved to bear their tremendous bulk.

Impenetrable Armor: Nature’s Tank Design

Unlike modern armadillos with their flexible banded shells, glyptodonts possessed a single solid carapace constructed from thousands of interlocking bony plates called osteoderms. This dome-shaped armor created an almost impenetrable fortress that could reach up to 2 inches (5 centimeters) in thickness in the largest species. The carapace was not simply a protective cover but a sophisticated structure with a honeycomb-like internal architecture that maximized strength while minimizing weight – an impressive feat of natural engineering. Each osteoderm featured unique surface patterns that varied between species, allowing paleontologists to identify different glyptodont types from even small fragments of their armor. The immovable nature of this shell meant that, unlike modern armadillos, glyptodonts couldn’t roll into a ball for protection; instead, they relied on their sheer size and additional specialized defenses to deter predators. This extraordinary armor effectively transformed these mammals into living tanks, capable of withstanding attacks from even the most formidable Pleistocene predators.

Weaponized Tails: The Prehistoric Mace

Perhaps the most spectacular adaptation of certain glyptodont species was their tail weaponry. Species like Doedicurus possessed a tail encased in bony rings and terminating in a large spiked club that resembled a medieval mace. These tail clubs could measure up to 3 feet (1 meter) in diameter and were studded with sharp bony spikes or knobs. Scientific analysis suggests these tails were actively used as defensive weapons, capable of delivering devastating blows to predators or competing males during territorial disputes. The vertebrae in the tail featured specialized interlocking joints that would have allowed for powerful side-to-side swinging motions while maintaining structural integrity. Biomechanical studies indicate that a full-force swing from a glyptodont’s tail club could deliver enough energy to break bones or cause fatal internal injuries to even large predators like the saber-toothed cat Smilodon. This combination of impenetrable armor and offensive capability made glyptodonts one of the most well-defended herbivores of their time, representing an evolutionary arms race between predator and prey.

Dietary Habits of the Car-Sized Herbivores

Despite their intimidating appearance, glyptodonts were strict herbivores, using their peg-like teeth to process vegetation throughout the diverse landscapes they inhabited. Their dental structure was markedly different from modern armadillos, consisting of simplified teeth with continuous growth that resembled columns or lobes rather than the sharper, more varied dentition of their modern relatives. This specialized dental arrangement was perfectly adapted for grinding tough plant material, including grasses, roots, and possibly tougher vegetation that grew in their habitats. Analysis of fossilized glyptodont dung and tooth wear patterns indicates they were primarily grazers that consumed large quantities of grass and other ground-level vegetation. Their massive size meant they required substantial daily food intake, likely spending most of their waking hours feeding to maintain their enormous bulk. Unlike many other large herbivores, their heavily armored bodies meant they didn’t need to move quickly or travel long distances to escape predators, allowing them to develop a relatively sedentary lifestyle focused on efficient digestion of fibrous plant material.

Geographic Range and Habitat Adaptations

Glyptodonts initially evolved in South America but later expanded their range northward after the formation of the Isthmus of Panama approximately 3 million years ago. This geological event, known as the Great American Interchange, allowed these armored giants to spread throughout Central America and into what is now the southern United States. Fossil evidence shows they inhabited diverse environments ranging from grasslands and savannas to woodlands and even semi-arid regions. Different species developed specific adaptations to thrive in their particular habitats – some with broader shells adapted for open grasslands, while others had narrower carapaces better suited for navigating between trees in more wooded areas. Their fossils have been discovered across an impressive geographic range, from Argentina and Brazil in South America to Mexico and states like Florida, Texas, and Arizona in North America. This wide distribution demonstrates their remarkable success as a group, having conquered diverse ecosystems across two continents during their evolutionary reign.

Social Structure and Reproductive Strategies

While much about glyptodont behavior remains speculative, paleontologists have developed theories about their social structures based on fossil evidence and comparisons with modern relatives. Many experts believe these giants likely lived in small family groups or loose herds, particularly in open grassland habitats where group living offers protection advantages. Their reproductive rate was probably quite slow, with females likely giving birth to single, well-developed offspring after extended gestation periods – a common pattern among large mammals. Young glyptodonts would have been born with softer, more flexible carapaces that hardened and grew as they matured, gradually developing the characteristic armor of adults. The substantial parental investment required to raise such large offspring suggests they may have had extended periods of maternal care, with juveniles potentially staying with their mothers until reaching substantial size themselves. This slow reproductive strategy would have been sustainable due to their formidable defenses, which would have ensured relatively high adult survival rates compared to many other prehistoric herbivores.

Remarkable Fossil Discoveries

Some of the most spectacular glyptodont fossils have been discovered in the Pampas region of Argentina and neighboring areas of South America, where complete or nearly complete specimens have been unearthed. One of the most famous discoveries occurred in the late 19th century when naturalist Charles Darwin collected glyptodont fossils during his voyage on the HMS Beagle, specimens that would later contribute to his groundbreaking theories on evolution. More recently, in 2015, farmers in Argentina discovered an almost perfectly preserved glyptodont shell measuring nearly 5 feet (1.5 meters) in diameter along the banks of a dried-up river. The exceptional preservation of many glyptodont fossils is largely due to their robust armor, which resisted decomposition far better than the skeletal remains of most other animals. This has provided scientists with detailed information about their physical structure and appearance. The discovery of multiple individuals at certain sites has also offered clues about potential social groupings, with some locations yielding evidence that suggests these animals may have gathered in particular areas, possibly for protection or access to resources.

Extinction Theories: Why They Disappeared

The extinction of glyptodonts occurred relatively recently in geological terms, with most species disappearing around 10,000-12,000 years ago during the end of the Pleistocene epoch. This timing coincides with two major events: dramatic climate changes associated with the end of the last ice age and the arrival and spread of human populations throughout the Americas. The debate about which factor played the larger role continues among paleontologists, with evidence supporting both as contributing causes. The climate shift at the end of the Pleistocene altered vegetation patterns across their range, potentially reducing available food sources for these massive herbivores. Simultaneously, newly arrived human hunters may have targeted these animals for their meat, which would have represented an enormous food resource for early communities. Their slow reproduction rates would have made glyptodont populations particularly vulnerable to even modest hunting pressure. Most scientists now favor a combination of these factors as the most likely explanation, with climate change stressing populations that were then pushed to extinction by human predation – a pattern seen with many other megafauna species that disappeared during this same period.

Comparison to Modern Armadillos

Modern armadillos represent the living descendants of the lineage that also produced glyptodonts, though today’s species are significantly different in many respects. The most obvious distinction is size – while glyptodonts reached car-crushing proportions, even the largest living armadillo species are relatively modest in comparison. Another key difference lies in their armor structure – modern armadillos possess flexible bands in their carapace that allow for movement and, in some species, the ability to roll into a protective ball, whereas glyptodonts had rigid, immovable shells. The dental structures also differ significantly, with modern armadillos having simpler, peg-like teeth adapted for their insectivorous or omnivorous diets, unlike the specialized grinding teeth of their giant ancestors. However, both groups share fundamental anatomical features that confirm their evolutionary relationship, including specific skeletal modifications in the vertebrae and pelvis that characterize all xenarthrans. Modern armadillos essentially represent the more adaptable, smaller-bodied branch of this ancient lineage – one that survived the extinction event that claimed their larger relatives and continues to thrive in various ecosystems throughout the Americas today.

Scientific Importance and Research Challenges

Studying glyptodonts presents unique challenges and opportunities for paleontologists seeking to understand megafaunal evolution and extinction. Their well-preserved fossils provide exceptional data about physical characteristics, but questions about behavior, physiology, and ecology must be inferred through indirect evidence and comparison with living relatives. Modern research techniques have revolutionized our understanding of these creatures, with CT scanning allowing scientists to examine the internal structure of their armor and skulls without damaging precious specimens. Biomechanical modeling has helped researchers understand how these massive animals moved and how their defensive adaptations functioned. DNA extraction and analysis from well-preserved specimens offer the tantalizing possibility of clarifying their precise evolutionary relationship to modern armadillos and other xenarthrans. Climate modeling combined with paleontological evidence continues to provide insights into their extinction, helping scientists understand the complex interplay between climate change and human activity that shaped the modern world. As research tools advance, our understanding of these remarkable animals continues to grow, offering valuable lessons about evolution, adaptation, and the vulnerability of even the most seemingly indestructible species to environmental change.

Cultural Impact and Popular Imagination

Giant armadillos have captured human imagination since their fossils were first discovered, appearing in natural history museum displays worldwide as crowd-drawing exhibits. Their incredible size and alien-yet-familiar appearance make them particularly fascinating to the public, often serving as ambassadors for paleontology education. In popular culture, glyptodonts have appeared in documentary series like “Walking with Beasts” and have inspired creatures in various films, games, and works of fiction. Indigenous cultures in South America incorporated these fossils into their mythology long before modern scientific discovery, with some tribes believing the giant shells were the remains of beings from the distant past or even shelters created by deities. Even today, the discovery of glyptodont fossils frequently makes headlines, bringing public attention to paleontology and the remarkable history of life on Earth. Their compelling story of evolutionary success followed by extinction continues to serve as a powerful reminder of how even the most impressively adapted creatures remain vulnerable to environmental change – a lesson with particular relevance in today’s world of accelerating climate shifts and biodiversity loss.

Ecosystem Engineers of Prehistoric Landscapes

Beyond their impressive physical characteristics, glyptodonts played crucial roles in shaping the ecosystems they inhabited, functioning as what ecologists today would call “ecosystem engineers.” Their feeding habits, which included consuming massive quantities of vegetation daily, would have significantly impacted plant communities and succession patterns across their range. As they moved through landscapes, their enormous weight created trails and cleared areas that could have facilitated movement for other animals or created microclimates for certain plant species. Their wallowing behavior, similar to that observed in modern elephants and rhinos, likely created depressions that collected water and served as microhabitats for numerous smaller species. Perhaps most importantly, as massive herbivores, they would have been responsible for considerable nutrient cycling, with their dung fertilizing large areas and supporting diverse insect communities. The burrows of smaller glyptodont species may have provided shelter for other animals after being abandoned, similar to how modern large armadillo burrows support biodiversity in today’s ecosystems. The extinction of these ecosystem engineers would have triggered cascading effects throughout their habitats, fundamentally altering ecological dynamics across the Americas in ways that continue to influence these ecosystems today.

Conclusion

The giant armadillos of prehistory represent one of evolution’s most remarkable experiments – mammals that developed car-crushing size combined with tank-like defenses. Though they vanished from Earth thousands of years ago, glyptodonts left behind an extraordinary fossil legacy that continues to fascinate scientists and the public alike. Their story illustrates the incredible diversity of life that has existed on our planet and demonstrates how dramatically different even closely related animal groups can become through evolutionary processes. As we face contemporary challenges of climate change and biodiversity loss, these ancient armored giants offer valuable perspectives on adaptation, specialization, and vulnerability. Though we will never see a living glyptodont crushing a car beneath its massive weight, their fossils ensure these remarkable creatures remain an important part of Earth’s biological story, continuing to educate and inspire new generations about our planet’s extraordinary evolutionary history.