In the dusty badlands of northern Montana, among layers of ancient sediment dating back to the Late Cretaceous period, paleontologists uncovered the remains of a fascinating horned dinosaur—Rubeosaurus ovatus. This enigmatic ceratopsian, whose name means “ruby lizard” in reference to the Ruby Mountains near its discovery site, has puzzled scientists since its initial identification and continues to spark debate within paleontological circles today. With its distinctive frill and horn arrangement, Rubeosaurus represents an important piece in understanding the diversity and evolution of horned dinosaurs that once roamed North America approximately 75 million years ago.

Discovery and Naming Controversy

The story of Rubeosaurus begins in 1928 when paleontologist Charles W. Gilmore described a partial skull and skeletal elements collected from the Two Medicine Formation in Montana. Initially, Gilmore classified these remains as belonging to Styracosaurus ovatus, a close relative of the more famous Styracosaurus albertensis from Alberta, Canada. For decades, these fossils remained classified under Styracosaurus, until a 2010 study by Andrew T. McDonald and John R. Horner proposed that the distinctive horn and frill arrangement warranted designation as a separate genus—thus Rubeosaurus was born. The naming has not been without controversy, however, as some researchers still argue that the differences are insufficient for a new genus, highlighting the ongoing challenges in classifying fragmentary dinosaur remains.

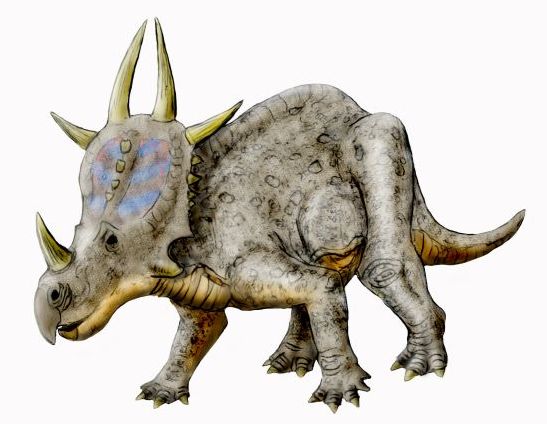

Physical Characteristics

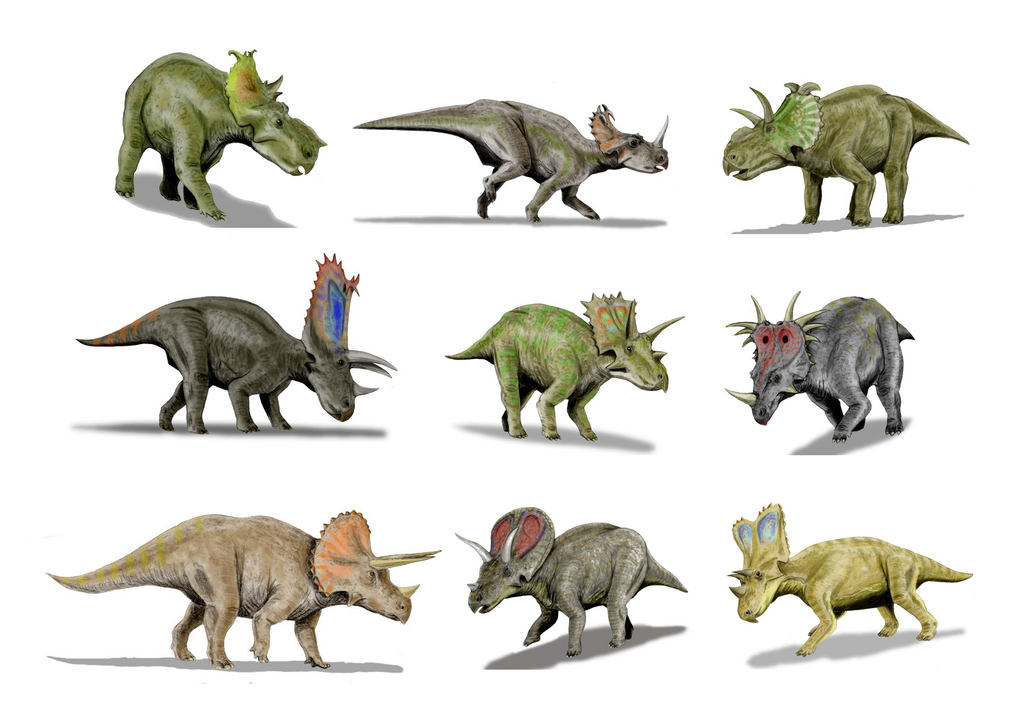

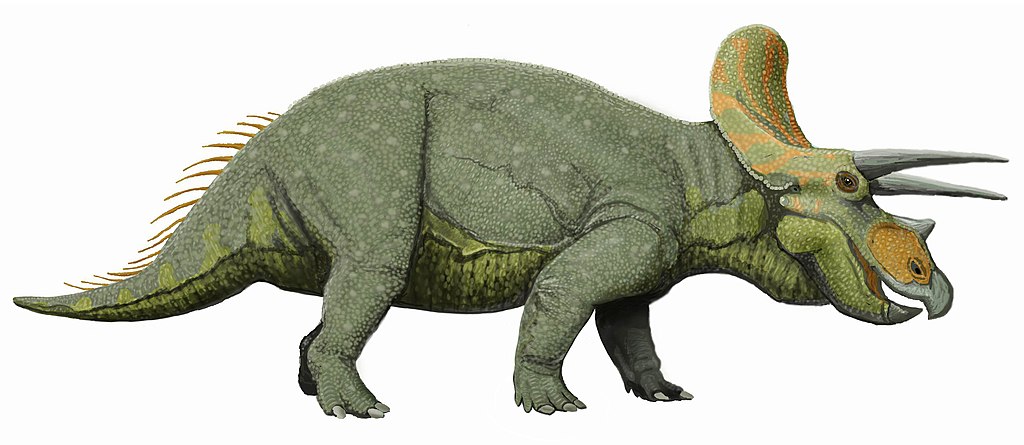

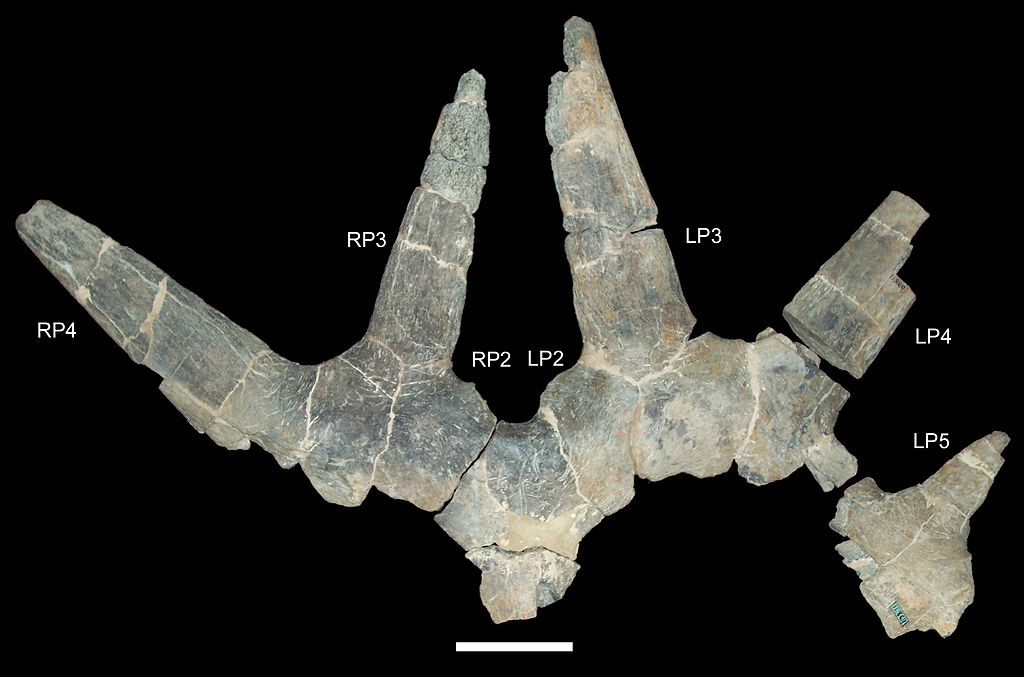

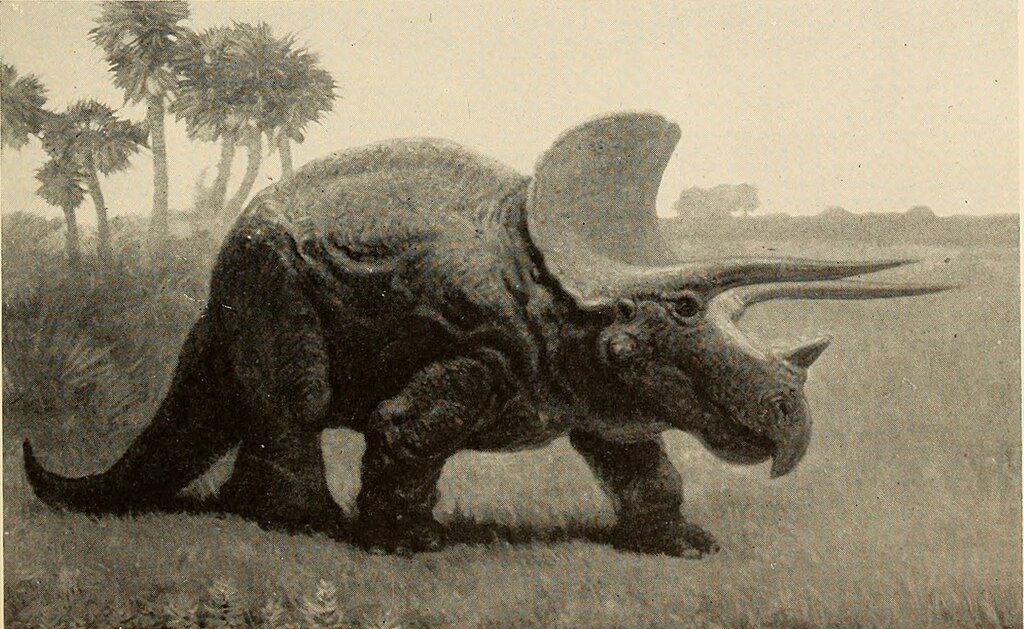

Rubeosaurus was a medium-sized ceratopsian dinosaur, estimated to have reached lengths of approximately 6 meters (20 feet) from beak to tail tip. Like other members of the Centrosaurinae subfamily, it possessed a large nasal horn projecting upward from its snout and a relatively short yet ornate neck frill adorned with distinctive spikes. What sets Rubeosaurus apart from its relatives is the particular arrangement of these frill ornamentations—it featured particularly long, forward-curving spikes projecting from the parietal bone (the rear portion of the frill), with the P1 spike position being especially elongated and distinctive. The dinosaur likely weighed between 1.5 to 2 tons, with a bulky body supported by four column-like legs, similar to a modern rhinoceros in general body plan but with its unique headgear.

Taxonomic Classification

Rubeosaurus belongs to the Ceratopsidae family, a group of horned, herbivorous dinosaurs that flourished during the Late Cretaceous period. More specifically, it’s classified within the subfamily Centrosaurinae, which is characterized by members having a prominent nasal horn and relatively shorter, more ornate frills compared to their cousins in the Chasmosaurinae subfamily. The centrosaurines underwent an impressive adaptive radiation in western North America, giving rise to numerous species with increasingly elaborate head ornamentation. Within this subfamily, Rubeosaurus appears most closely related to Styracosaurus, with which it was originally classified, and Einiosaurus, another Montana ceratopsian with distinctively forward-curving horn projections. This placement in the evolutionary tree suggests Rubeosaurus was part of a regional radiation of centrosaurines that developed increasingly specialized frill and horn morphologies.

The Two Medicine Formation Ecosystem

The Two Medicine Formation where Rubeosaurus fossils were discovered represents a rich paleoenvironmental setting from the Late Cretaceous period, approximately 75-74 million years ago. During this time, the region that would become Montana was situated much closer to the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that divided North America. The environment consisted of coastal plains and river valleys with seasonal rainfall patterns, supporting diverse plant life including conifers, ferns, and early flowering plants. Rubeosaurus shared this ecosystem with other notable dinosaur species including the duck-billed hadrosaur Maiasaura, the small carnivorous Troodon, and fellow ceratopsian Einiosaurus. The formation has been particularly significant for paleontologists because it preserves evidence of dinosaur nesting grounds and juvenile specimens, providing insights into dinosaur reproduction and growth that complement our understanding of Rubeosaurus and its contemporaries.

Diet and Feeding Adaptations

As a ceratopsian dinosaur, Rubeosaurus was exclusively herbivorous, equipped with a specialized feeding apparatus for processing tough Cretaceous vegetation. Its beak-like structure at the front of the jaws, formed by the rostral and predentary bones, would have been ideal for cropping vegetation close to the ground. Behind this beak was a formidable battery of teeth arranged in dental batteries—continuous rows of teeth that were constantly replaced throughout the animal’s lifetime, ensuring efficient grinding surfaces were always available for processing fibrous plant material. The jaw mechanics of Rubeosaurus allowed for powerful vertical crushing motions rather than the side-to-side chewing motion seen in mammals. Based on the plant fossils found in the Two Medicine Formation, Rubeosaurus likely fed on cycads, ferns, and early flowering plants that composed the understory of Late Cretaceous forests, possibly using its beak to selectively strip leaves from branches or uproot tougher vegetation.

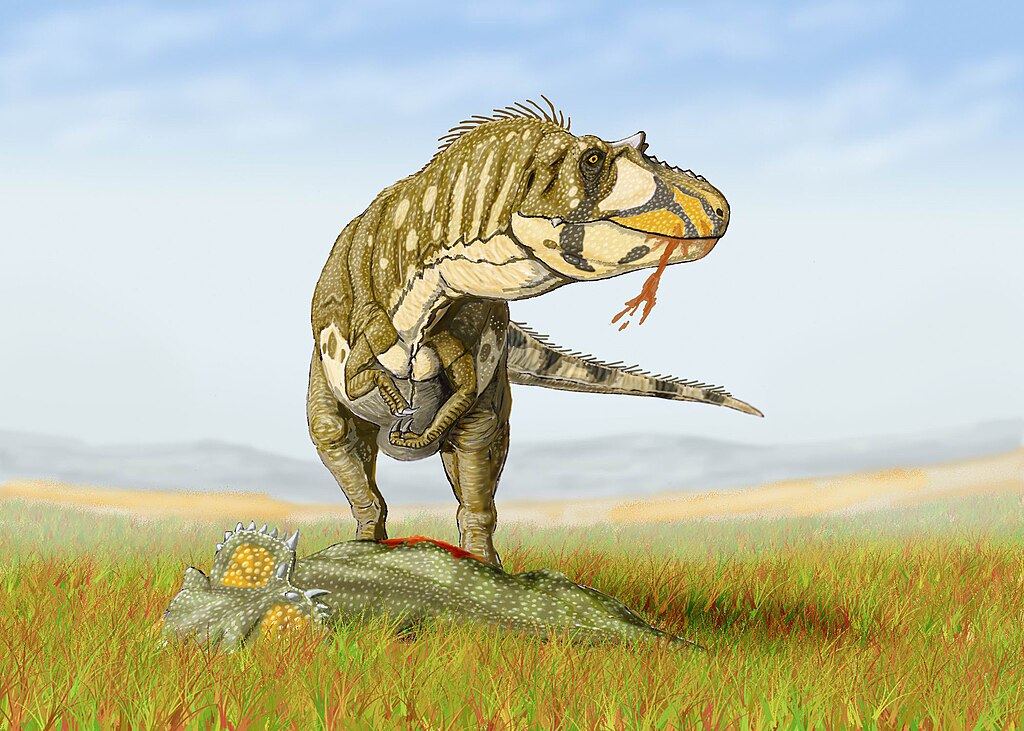

Function of the Elaborate Frill and Horns

The striking frill and horn arrangement that makes Rubeosaurus so distinctive has been the subject of significant scientific debate regarding its primary function. Multiple hypotheses exist, with the most prominent being that these structures served as visual display features for species recognition and sexual selection. The elaborate ornamentation may have allowed individuals to recognize potential mates from the same species in environments where multiple ceratopsian species coexisted. Additionally, these features could have played crucial roles in competition between males for mating opportunities, with more impressive displays potentially signaling genetic fitness to potential mates. Other proposed functions include thermoregulation, with the highly vascularized frill potentially serving as a radiator to dissipate excess body heat, and defense against predators like Daspletosaurus, a tyrannosaur known from the same formation. Most likely, the horns and frill served multiple functions simultaneously, evolving through complex selection pressures that favored increasingly elaborate structures.

Growth and Development

Understanding the growth patterns of Rubeosaurus remains challenging due to the limited fossil material available, but comparative studies with better-known ceratopsians provide valuable insights. Like other large-bodied dinosaurs, Rubeosaurus likely experienced rapid growth during its juvenile and subadult phases before reaching sexual maturity. The distinctive frill ornamentation that characterizes adult specimens would have developed gradually, with the elaborate spikes becoming more pronounced as individuals matured. Studies of bone histology in related ceratopsians suggest that these animals reached adult size within 15-20 years, though sexual maturity may have been attained earlier. Particularly interesting is how the head ornamentation would have changed throughout development, potentially serving different social functions at different life stages. Young Rubeosaurus individuals likely looked quite different from adults, possibly allowing for niche partitioning within the species, with juveniles exploiting different food resources than fully grown individuals.

Social Behavior and Herd Structure

While direct evidence of Rubeosaurus social behavior is limited, paleontologists can make educated inferences based on related ceratopsians for which more abundant fossil evidence exists. Bone beds containing multiple individuals of related centrosaurines suggest these animals often lived and traveled in herds, potentially offering protection against predators and increasing foraging efficiency. The age distribution within these bone beds indicates that herds may have included individuals of various ages, from juveniles to fully mature adults, suggesting complex social structures similar to those seen in modern elephants or bison. The elaborate display structures of Rubeosaurus would have been particularly valuable in a social context, potentially serving as visual signals that established dominance hierarchies within herds or attracted mates during breeding seasons. Some researchers have proposed that different ceratopsian species, including Rubeosaurus, may have engaged in seasonal migrations to follow food resources across the ancient landscapes of Montana, though direct evidence for such behaviors remains elusive.

The Ongoing Identity Puzzle

One of the most intriguing aspects of Rubeosaurus is the continuing debate about its taxonomic validity. The genus has experienced a complicated classification history that reflects broader challenges in paleontological taxonomy. After McDonald and Horner established the genus in 2010, subsequent research by McDonald in 2011 actually questioned this separation and suggested that the specimens might instead belong to Styracosaurus ovatus after all. By 2017, further analysis by Chiba and colleagues proposed that Rubeosaurus might actually represent specimens of Einiosaurus, another horned dinosaur from the same formation. This taxonomic uncertainty stems from the fragmentary nature of fossil material, the significant individual variation present within ceratopsian species, and the challenges of defining clear boundaries between closely related taxa that existed along an evolutionary continuum. The Rubeosaurus case exemplifies how paleontological classifications remain dynamic and subject to revision as new specimens are discovered and analytical techniques improve.

Biogeographical Significance

Regardless of its precise taxonomic placement, the dinosaur known as Rubeosaurus represents an important data point in understanding the biogeography of Late Cretaceous North America. The Two Medicine Formation preserves a dinosaur fauna that evolved in partial geographical isolation from contemporaneous dinosaur communities in what is now Alberta, Canada. These Canadian formations, including the Dinosaur Park Formation, contain different but related ceratopsian species, suggesting geographical barriers may have facilitated allopatric speciation—the evolution of new species due to geographical isolation. The distinctive characteristics of Rubeosaurus compared to its northern relatives provide evidence for dinosaur provincialism, where different regions supported distinct dinosaur communities despite their relatively close proximity. This pattern aligns with broader evidence suggesting that dinosaur species in the Late Cretaceous had more restricted geographical ranges than previously thought, potentially due to ecological specialization and geographical barriers like river systems or mountain ranges that limited dispersal.

Extinction Context

Rubeosaurus existed during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous, approximately 10 million years before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction event that would claim all non-avian dinosaurs. However, the centrosaurine ceratopsians as a group were already experiencing significant evolutionary changes and potential decline before the asteroid impact. The Two Medicine Formation records an interesting transition period in ceratopsian evolution, with Rubeosaurus representing one of several highly specialized forms that evolved during this time. These elaborate horn and frill arrangements may reflect an evolutionary “arms race” in display structures driven by sexual selection. Interestingly, by the very end of the Cretaceous, centrosaurines like Rubeosaurus had largely disappeared from the fossil record in North America, replaced by chasmosaurine ceratopsians like Triceratops in the final few million years before the extinction event. This suggests that the decline of centrosaurines like Rubeosaurus may have resulted from competition with other herbivores or changing environmental conditions rather than the ultimate asteroid impact.

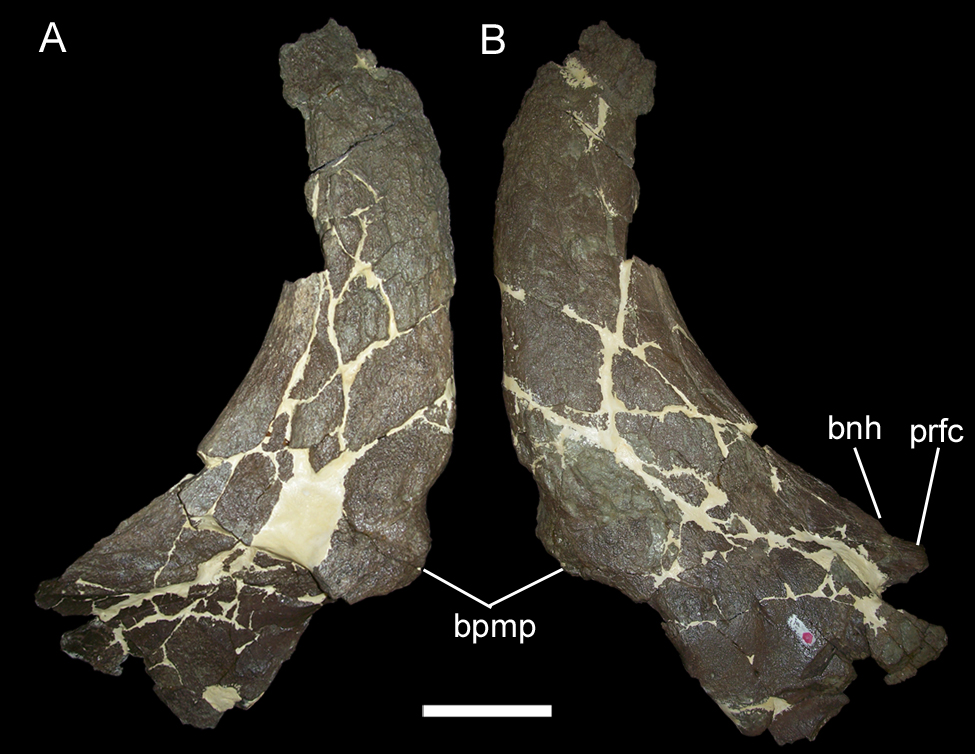

Discovery Timeline and Key Fossils

The material that would eventually be classified as Rubeosaurus has a fascinating collection history spanning nearly a century. The holotype specimen, USNM 11869, consists of a partial skull with a distinctive frill, originally collected by George F. Sternberg during a 1928 expedition to the Two Medicine Formation. For decades, this specimen remained in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Natural History, classified as Styracosaurus ovatus. Additional material tentatively assigned to Rubeosaurus includes isolated frill fragments and postcranial elements collected during subsequent expeditions to the Two Medicine Formation. Particularly important was the discovery of a more complete frill section in the 1980s that revealed the distinctive spike arrangement used to distinguish Rubeosaurus from Styracosaurus. Unlike some other ceratopsian dinosaurs, no complete Rubeosaurus skeleton has been discovered to date, which contributes to the ongoing uncertainty regarding its exact appearance and taxonomic status.

Paleontological Significance and Future Research

Despite its contested taxonomic status, Rubeosaurus remains significant in paleontological research for several reasons. It represents an important data point in understanding the diversity and evolution of ceratopsian dinosaurs, particularly the trend toward increasingly elaborate display structures in the centrosaurine subfamily. The genus also highlights the distinct dinosaur communities that evolved in the northern Montana region during the Late Cretaceous, contributing to our understanding of dinosaur provincialism and biogeography. Future research directions that might resolve questions surrounding Rubeosaurus include detailed comparative morphometric analyses of all centrosaurine specimens from the Two Medicine Formation, investigation of ontogenetic changes in frill morphology, and the application of new technologies like CT scanning to better understand internal structures. The most valuable contribution would come from discovery of additional, more complete specimens that could clarify the relationships between Rubeosaurus and related genera like Einiosaurus and Styracosaurus. Until such discoveries are made, Rubeosaurus will remain somewhat mysterious—a testament to the ongoing nature of paleontological research.

Conclusion

Rubeosaurus represents a fascinating case study in paleontological discovery and classification. From its initial identification as Styracosaurus ovatus to its designation as a distinct genus and subsequent taxonomic debates, this horned dinosaur from Montana epitomizes the dynamic nature of scientific understanding. Whether Rubeosaurus ultimately stands as a valid genus or is eventually reassigned, its distinctive frill and horn arrangement provides valuable insights into the diversity of ceratopsian dinosaurs that once roamed North America. As paleontologists continue to unearth new specimens and develop enhanced analytical techniques, our understanding of these magnificent creatures will continue to evolve—much like the dinosaurs themselves did during their remarkable evolutionary journey through the Mesozoic Era.