The Bone Wars, also known as the “Great Dinosaur Rush,” represents one of the most contentious scientific rivalries in American history. In the late 19th century, two prominent paleontologists—Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope—engaged in a bitter competition that dramatically advanced our knowledge of dinosaurs while simultaneously destroying their professional reputations and personal finances. Their decades-long feud, characterized by sabotage, theft, and public humiliation, transformed paleontology from a gentlemanly pursuit into a cutthroat scientific discipline. This rivalry ultimately yielded the discovery and naming of more than 136 new dinosaur species, laying the groundwork for our modern understanding of these prehistoric creatures, but at tremendous personal and professional cost.

The Origins of a Legendary Rivalry

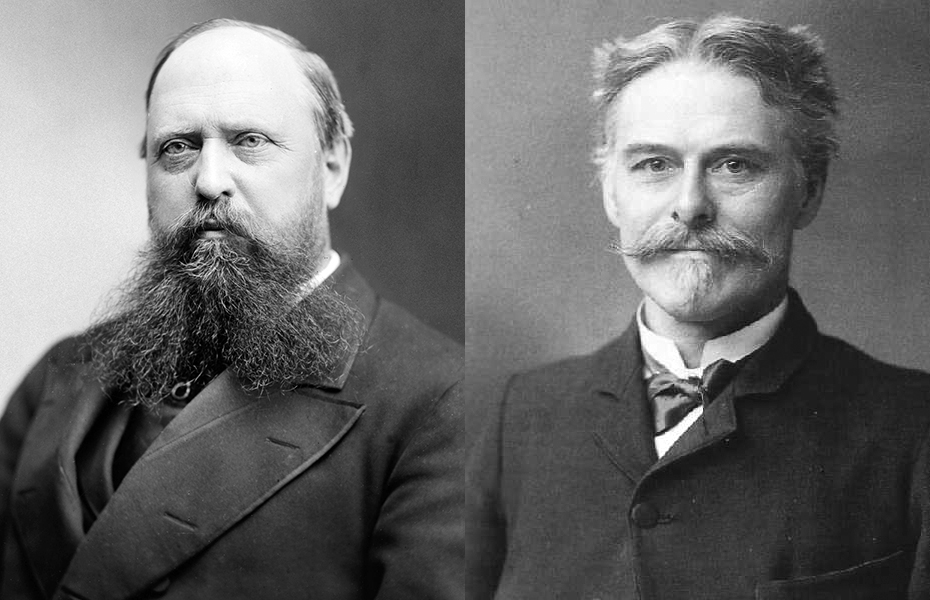

The seeds of the Bone Wars were planted in 1864 when Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh first met in Berlin while studying under the renowned paleontologist Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer. Initially, their relationship was cordial and even friendly, with the two scientists sharing discoveries and corresponding regularly. Cope, the son of a wealthy Quaker merchant from Philadelphia, had published his first scientific paper at age 18 and was regarded as a prodigy in natural sciences. Marsh, nephew of the wealthy philanthropist George Peabody, used his uncle’s financial backing to secure a position at Yale University and establish the Peabody Museum of Natural History. Their friendship deteriorated rapidly in 1868 when Marsh allegedly paid quarrymen in New Jersey to divert fossils meant for Cope to his own collection instead, marking the beginning of what would become one of science’s most notorious feuds.

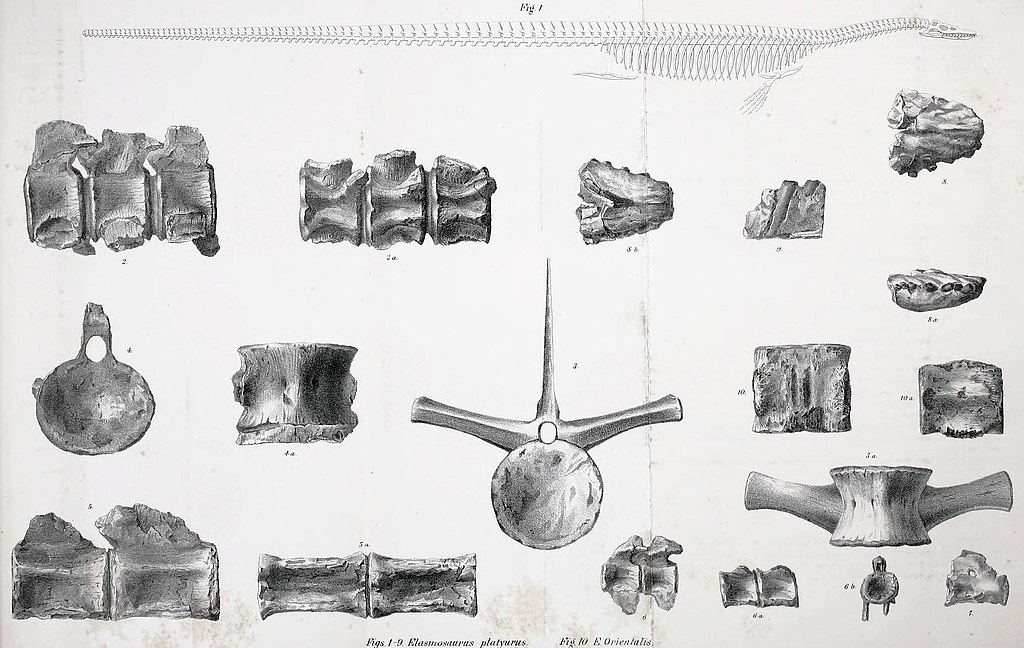

The Elasmosaurus Blunder

The incident that truly ignited the Bone Wars occurred in 1868 when Cope made a devastating scientific error while reconstructing an Elasmosaurus platyurus fossil. In his haste to publish, Cope mistakenly placed the creature’s skull on the end of its tail rather than its neck, creating an anatomical impossibility. Marsh publicly pointed out this embarrassing error during a meeting at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, humiliating Cope in front of his colleagues. When Cope attempted to purchase and destroy all copies of the published research containing his mistake, Marsh ensured copies remained in circulation. This public humiliation transformed their professional rivalry into a deeply personal vendetta, with Cope reportedly declaring that from that moment forward, “the war was on.” The incident not only damaged Cope’s scientific reputation but established a pattern of public criticism and attempts to discredit each other that would characterize their relationship for decades to come.

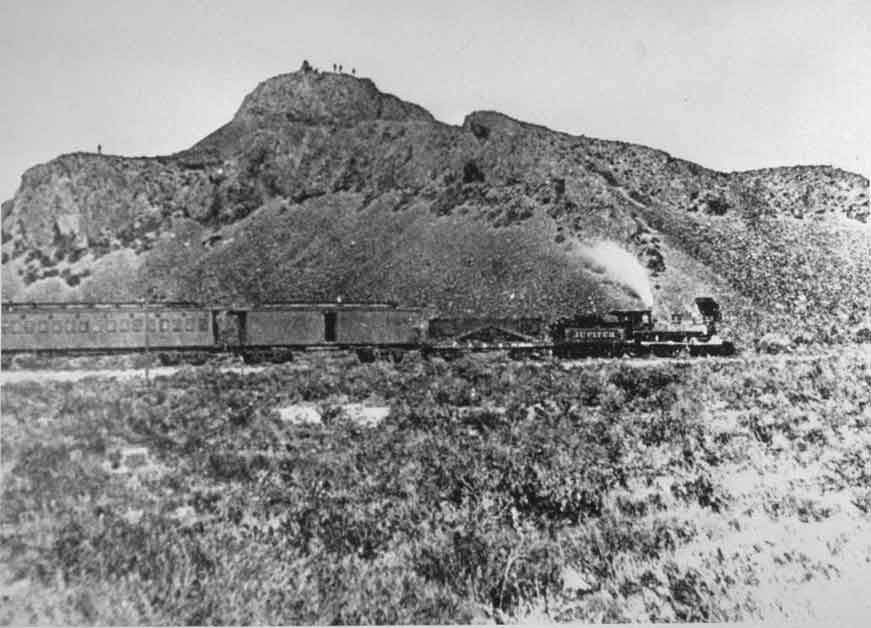

The Rush to the American West

By the early 1870s, both paleontologists turned their attention to the fossil-rich territories of the American West, particularly Wyoming, Colorado, and Nebraska. This shift marked the beginning of the most intense period of the Bone Wars. The completion of the transcontinental railroad in 1869 had opened these previously inaccessible regions to scientific exploration, revealing dinosaur fossils of unprecedented quality and quantity. Marsh, backed by his position at Yale and his uncle’s fortune, organized large expeditions with military escorts through the newly established U.S. Geological Survey. Cope, using his inheritance and working through the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, mounted competing expeditions. Both men rushed to claim new fossil sites, often working in dangerous frontier conditions and hostile Native American territories. Their frantic pace of discovery was unprecedented in paleontological history, with each man attempting to outdo the other in finding, naming, and publishing descriptions of new species before his rival could stake a claim.

Espionage and Sabotage in the Field

As the rivalry intensified, both Marsh and Cope resorted to increasingly underhanded tactics to undermine each other’s work. They hired spies to infiltrate each other’s dig sites, bribed railroad workers to misdirect fossil shipments, and even dynamited their own excavations to prevent the other from accessing specimens they couldn’t immediately collect. Marsh’s field collector, Samuel Williston, later revealed how Marsh instructed his teams to destroy fossils they couldn’t take with them to prevent Cope from finding them. Similarly, Cope’s collectors would spread false information about promising sites to mislead Marsh’s teams. The two paleontologists frequently poached each other’s workers, offering higher wages for information about new discoveries. In one particularly notorious incident, Cope’s team reportedly dumped plaster of Paris into a stream that Marsh’s workers were using as a water source, ruining their plaster supply and temporarily halting their ability to properly preserve fossils. These tactics reflected how scientific ethics had become secondary to the personal vendetta between the two men.

The Como Bluff Dinosaur Bonanza

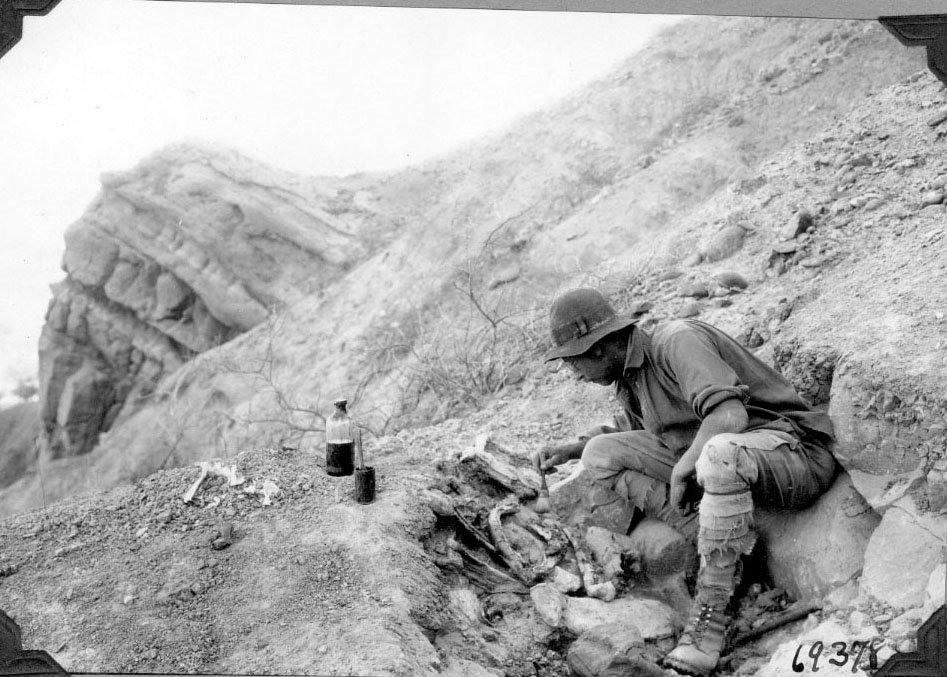

The discovery of the Como Bluff fossil beds in Wyoming in 1877 marked a crucial turning point in the Bone Wars, yielding some of the most spectacular dinosaur specimens ever found. When railroad workers William Harlow Reed and William Edward Carlin discovered massive bones protruding from hillsides near the Union Pacific Railroad line, they contacted Marsh, who quickly dispatched teams to the site. The Como Bluff quarries proved extraordinarily productive, yielding complete skeletons of Jurassic dinosaurs including Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, Apatosaurus, and Diplodocus. When Cope learned of the discovery, he immediately sent his own collectors to establish competing quarries in the region. The competition for Como Bluff specimens became so intense that Marsh’s workers reportedly worked at night by lantern light to avoid being observed by Cope’s men. Over the next decade, tons of fossils were excavated from Como Bluff, with both scientists rushing specimens to the East Coast, often resulting in hasty and inaccurate descriptions as they raced to publish first. The site’s extraordinarily preserved specimens fundamentally transformed understanding of dinosaur diversity and anatomy despite the less-than-ideal scientific practices employed in their collection.

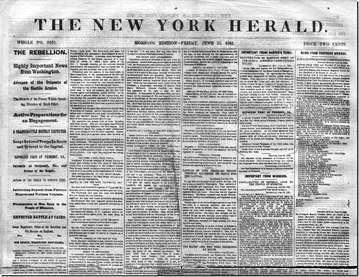

Media Manipulation and Public Attacks

By the 1880s, the Bone Wars had transcended scientific circles to become public entertainment through newspapers and magazines. Both Marsh and Cope actively courted journalists, providing sensationalized accounts of their discoveries while attacking each other’s scientific credibility. Cope kept a journal documenting what he considered Marsh’s scientific errors, which he intended to publish to destroy his rival’s reputation. Marsh, who had stronger political connections, used his influence with the U.S. Geological Survey to limit Cope’s access to government-funded expeditions. The rivalry reached its public peak in January 1890 when Cope convinced The New York Herald to publish a series of articles attacking Marsh and the U.S. Geological Survey for corruption and scientific incompetence. Marsh retaliated with counterattacks in the same newspaper. The public spectacle embarrassed the scientific community and damaged both men’s standing among their peers, with the American Naturalist noting that their behavior had “brought paleontology into disrepute.” This media war revealed how personal animosity had completely overshadowed scientific objectivity in their relationship.

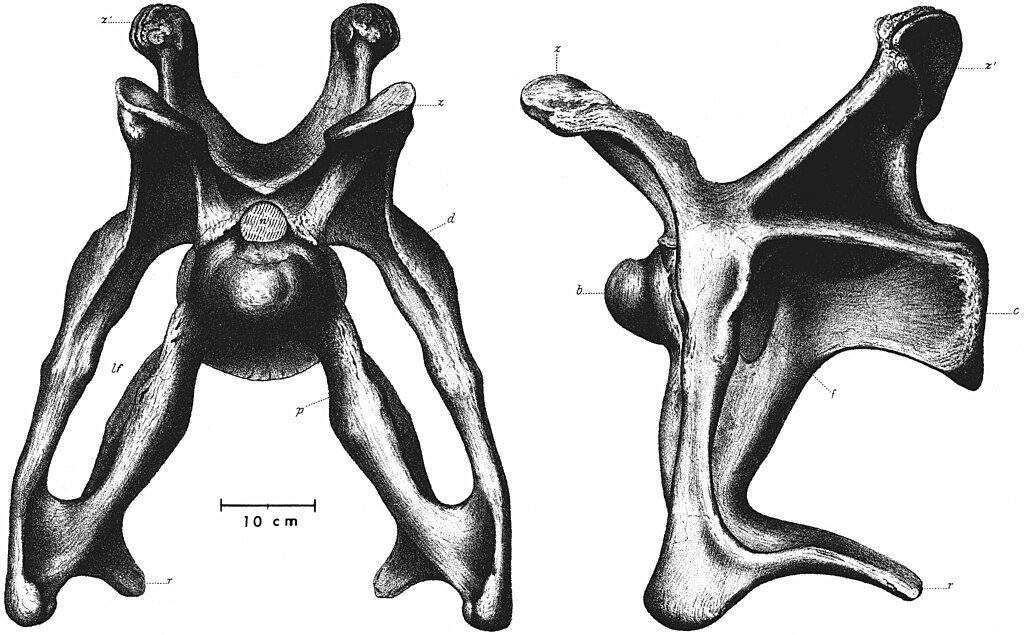

The Scientific Legacy: New Dinosaur Species

Despite their unprofessional conduct, the scientific output of the Bone Wars was remarkable, with Marsh and Cope collectively naming over 136 new dinosaur species. Marsh described and named iconic dinosaurs including Triceratops, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and Stegosaurus, while Cope discovered Camarasaurus, Coelophysis, Dimetrodon, and Monoclonius, among many others. Their discoveries fundamentally altered scientific understanding of the Mesozoic Era and established North America as a crucial region for paleontological research. The sheer volume of specimens they collected provided material for generations of subsequent paleontologists to study. However, their haste to publish before each other led to numerous scientific errors, including naming the same species multiple times under different names (a problem known as taxonomic synonymy) and assembling composite skeletons from multiple species. Modern paleontologists have spent decades revising and correcting their work, with some estimates suggesting that only 30-40% of the species they named were actually valid. Nevertheless, their contributions established dinosaur paleontology as a legitimate scientific field and sparked public fascination with these prehistoric creatures.

Financial Ruin and Personal Toll

The financial and personal costs of the Bone Wars were enormous for both scientists. Cope exhausted his substantial inheritance funding expeditions and publishing his findings, eventually being forced to sell much of his fossil collection to the American Museum of Natural History to cover his debts. In his final years, he lived in poverty in a small Philadelphia apartment, surrounded by remaining specimens and manuscripts. Marsh, despite his institutional backing from Yale and the U.S. Geological Survey, also faced financial difficulties as his obsession with outpacing Cope led to reckless spending. Both men sacrificed personal relationships in pursuit of their rivalry, with neither ever marrying or having children. Their singular focus on defeating each other consumed their lives, leaving them increasingly isolated within the scientific community. Colleagues gradually distanced themselves from both men as their behavior became more erratic and their attacks more personal. When they died—Cope in 1897 and Marsh in 1899—both were financially depleted and their once-sterling scientific reputations had been tarnished by decades of unprofessional conduct.

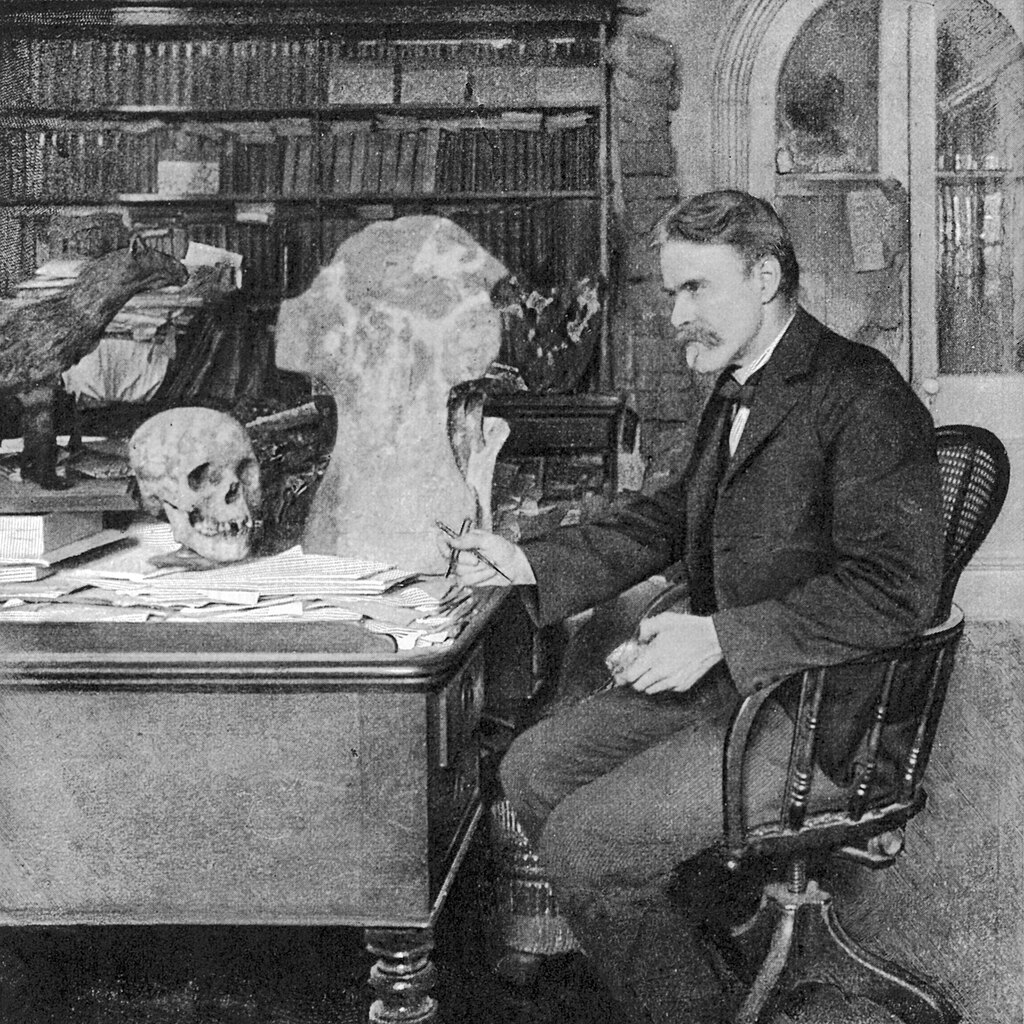

The Final Challenge: Cope’s Brain

Perhaps the most bizarre chapter in the Bone Wars saga came near its conclusion when Cope, approaching death in 1897, made an unusual final challenge to his lifelong rival. Cope arranged to have his body donated to science, with his skull to be preserved in the Anthropometric Society’s collection, essentially offering his brain for measurement and study. This peculiar request was Cope’s final attempt to prove his intellectual superiority over Marsh through cranial measurements, which were believed at the time to correlate with intelligence. Cope believed his brain would prove larger than Marsh’s, thus “winning” their contest even in death. Marsh, however, declined to participate in this posthumous competition, refusing to donate his own skull for comparison. Ironically, while Cope’s skeleton was indeed preserved, his brain was never properly measured due to inadequate preservation. This final, unfulfilled challenge symbolized the irrational extremes to which their rivalry had progressed, extending literally beyond the grave in a quest for supremacy that consumed both men’s lives.

Impact on Paleontological Methods

The frenetic pace and competitive nature of the Bone Wars transformed how paleontological fieldwork was conducted, creating both positive innovations and problematic practices that influenced the discipline for decades. Prior to Marsh and Cope, fossil collection was often a leisurely pursuit conducted by gentleman scientists with limited systematic methodology. The intense competition forced the development of more efficient excavation techniques, including the use of plaster jackets to protect fossils during transport and detailed field documentation systems. Both men employed teams of collectors who became skilled fossil hunters in their own right, establishing paleontological fieldwork as a specialized profession. However, their haste also established problematic precedents, including insufficient documentation of exact fossil locations and stratigraphic contexts, rushed excavations that damaged specimens, and secretive practices that limited scientific collaboration. The emphasis on quantity over quality and on speed over thoroughness created methodological problems that later generations of paleontologists had to overcome. Modern paleontological practices, with their emphasis on careful documentation and contextual information, developed partly in reaction to the excesses of the Bone Wars era.

The Scientific Aftermath and Corrections

After the deaths of Marsh and Cope, the scientific community faced the enormous task of sorting through their hasty work and correcting their numerous errors. Henry Fairfield Osborn at the American Museum of Natural History led much of this effort, systematically reviewing their publications and specimens throughout the early 20th century. The process of taxonomic revision revealed numerous instances where either Marsh or Cope had named the same species multiple times or had assembled composite skeletons from multiple species. The infamous case of Apatosaurus exemplifies these problems—Marsh named both Apatosaurus and Brontosaurus, which were later determined to be the same genus, with Apatosaurus taking precedence by scientific naming conventions. Similarly, Cope’s Monoclonius specimens were later found to represent several distinct ceratopsian dinosaurs. The sorting out of these taxonomic problems continues even today, with modern techniques like CT scanning and molecular analysis helping to resolve questions left by the Bone Wars. Despite these corrections, the vast collections amassed by both men provided the foundation for major museum dinosaur displays and continue to yield new scientific insights through reexamination with advanced technologies.

Cultural Impact and Public Perception

The Bone Wars significantly shaped public perception of dinosaurs and paleontology, creating enduring cultural impacts that extend far beyond scientific circles. Newspaper coverage of the rivalry introduced dinosaurs to the American public, transforming these prehistoric creatures from scientific curiosities into objects of popular fascination. The first major museum displays of dinosaur skeletons, assembled from Cope and Marsh specimens, became attractions that drew unprecedented crowds and established natural history museums as important cultural institutions. Early fictional portrayals of paleontologists in literature and later in film often drew inspiration from the adventurous aspects of the Bone Wars, creating the stereotype of the fossil hunter as a rugged explorer venturing into wilderness in search of prehistoric treasures. The enduring public interest in dinosaurs, which supports everything from children’s toys to blockbuster films, can be traced in part to the publicity generated by this 19th-century scientific feud. Though few outside academic circles remember Cope and Marsh by name today, their legacy lives on in popular culture’s continuing fascination with the prehistoric world they helped uncover.

Lessons in Scientific Ethics

The Bone Wars serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of allowing personal rivalry to overshadow scientific integrity and collaboration. Modern scientific ethics courses often reference Marsh and Cope as a classic example of how competition can simultaneously drive discovery while undermining scientific rigor. Their rivalry demonstrates how personal ambition, when unchecked, can lead to ethical compromises including data manipulation, destruction of evidence, and rushed publication of unverified findings. The scientific community’s eventual rejection of their methods helped establish important ethical standards that emphasize transparency, collaboration, and thorough peer review. Modern paleontological practice, with its emphasis on detailed documentation, interdisciplinary collaboration, and conservation of fossil resources, developed partly as a reaction against the excesses of the Bone Wars. Perhaps most importantly, their story illustrates how science functions best as a collaborative enterprise rather than a competitive one, with knowledge building incrementally through the contributions of many researchers rather than through the efforts of lone scientific “conquerors.” The greatest tragedy of the Bone Wars may be contemplating what these two brilliant scientists might have accomplished had they worked together rather than against each other.

Conclusion

The Bone Wars represents a paradoxical chapter in scientific history—a period when personal animosity drove remarkable discovery while simultaneously undermining scientific integrity. The legacy of Marsh and Cope remains deeply ambiguous: they discovered hundreds of dinosaur species and established American paleontology as a world-leading scientific discipline, yet their methods violated basic principles of scientific ethics. Their collections formed the foundation of major museum dinosaur halls that have educated and inspired generations, while their rivalry cautions against placing personal ambition above scientific truth. Perhaps the most enduring lesson of the Bone Wars is that science advances not through competition alone but through a balance of individual brilliance and collaborative effort. As modern paleontologists continue to build upon, correct, and reinterpret the fossils unearthed during this remarkable period, the complex legacy of these two brilliant, flawed scientists continues to evolve—much like our understanding of the prehistoric creatures they devoted their lives to studying.