Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, might not be the first place that comes to mind when thinking about dinosaur fossils, yet this steel city harbors one of the most significant paleontological legacies in North America. The influence of industrialist Andrew Carnegie and his passion for dinosaurs transformed Pittsburgh into an unexpected fossil hotspot that continues to shape our understanding of prehistoric life. From spectacular museum collections to groundbreaking field discoveries, Pittsburgh’s dinosaur connection runs deeper than most realize, creating a rich heritage that bridges the industrial age with Earth’s ancient past.

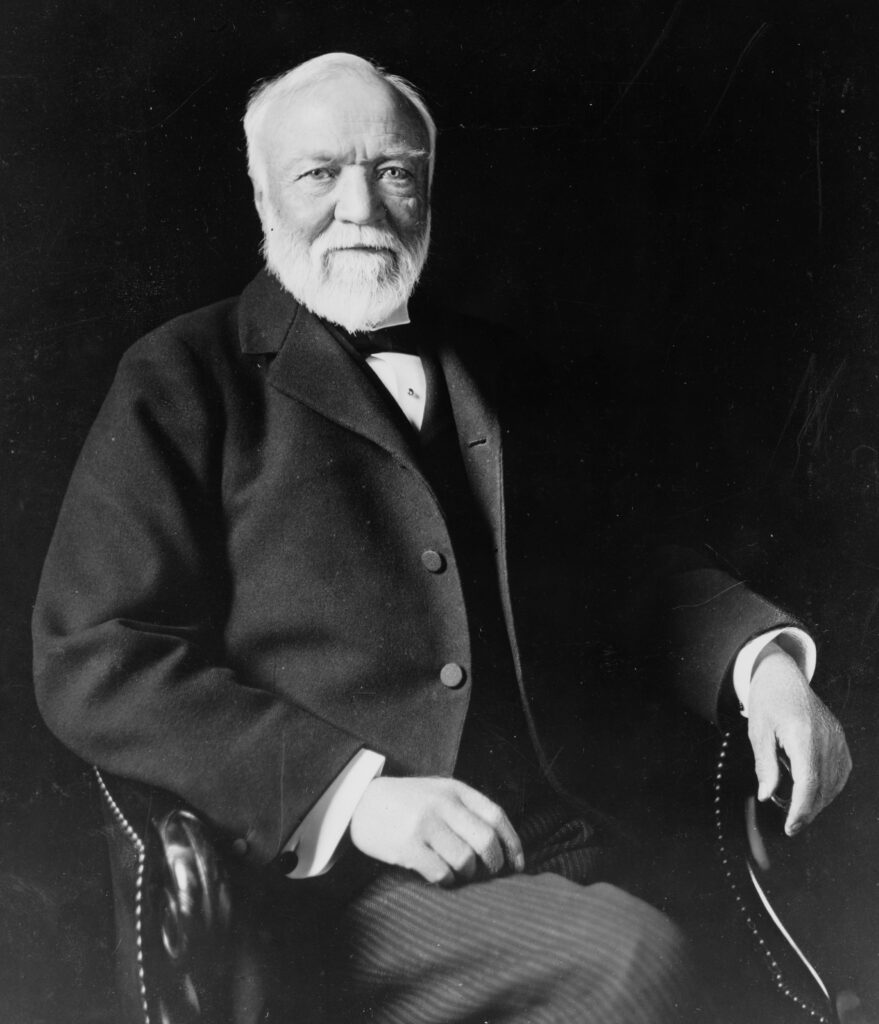

Andrew Carnegie’s Dinosaur Obsession

Andrew Carnegie, the steel magnate and philanthropist, developed a fascination with dinosaurs that would ultimately transform paleontology in America. Upon reading about the discovery of a massive dinosaur skeleton in Wyoming in 1899, Carnegie immediately instructed his team to acquire spectacular specimens for his hometown of Pittsburgh. This wasn’t merely a wealthy man’s whim but a strategic vision to bring world-class scientific resources to the industrial city he called home. Carnegie’s competitive nature drove him to pursue the most impressive dinosaur specimens, often engaging in what historians now call the “Bone Wars” against other wealthy collectors. His financial backing fundamentally changed how dinosaur expeditions were funded and conducted, establishing a legacy that would extend far beyond his lifetime and put Pittsburgh firmly on the paleontological map.

The Birth of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History

The Carnegie Museum of Natural History, established in 1896, became the institutional embodiment of Andrew Carnegie’s scientific ambitions for Pittsburgh. What began as a modest natural history collection rapidly evolved into one of the world’s premier dinosaur repositories following Carnegie’s dinosaur acquisition directive. The museum’s original building was designed around the enormous dinosaur specimens being excavated by Carnegie-funded expeditions, with specialized halls constructed to accommodate the massive skeletons. When the first complete Diplodocus skeleton was mounted in 1907, the museum instantly achieved international prominence in paleontological circles. Carnegie’s vision for the museum went beyond mere display – he established research facilities and hired leading scientists, creating an institution that would both exhibit spectacular fossils and advance scientific understanding. Today, the museum houses over 100,000 fossil specimens, forming one of the most comprehensive paleontological collections in existence and cementing Pittsburgh’s status as a world center for dinosaur research.

Diplodocus carnegii: Pittsburgh’s Dinosaur Ambassador

The most iconic dinosaur associated with Pittsburgh’s fossil legacy is undoubtedly Diplodocus carnegii, aptly named after its benefactor, Andrew Carnegie. Discovered in Wyoming in 1899, this massive sauropod dinosaur became the crown jewel of the Carnegie Museum’s collection and Pittsburgh’s unofficial prehistoric mascot. Measuring nearly 90 feet from nose to tail, the “Carnegie Diplodocus” represented one of the most complete specimens of its kind ever found. What truly distinguished this particular fossil was Carnegie’s unprecedented decision to create plaster casts of the entire skeleton and donate them to major museums worldwide. Between 1905 and 1913, replicas of Pittsburgh’s Diplodocus were installed in museums across London, Berlin, Paris, Vienna, Madrid, and other major cities, serving as dinosaur ambassadors that spread Pittsburgh’s paleontological influence globally. The gesture wasn’t merely philanthropic – it strategically positioned Pittsburgh as a center of scientific authority during a time when dinosaurs were capturing the public imagination worldwide.

The Jurassic Treasures of the Morrison Formation

Much of Pittsburgh’s dinosaur prominence stems from the museum’s extensive collection of fossils from the Morrison Formation, a geological layer dating to the Late Jurassic period, approximately 155-148 million years ago. The Carnegie Museum’s early expeditions focused heavily on this fossil-rich formation that stretches across the western United States, yielding some of the most iconic dinosaur specimens ever discovered. Beyond the famous Diplodocus, Carnegie-funded excavations unearthed spectacular specimens of Apatosaurus, Allosaurus, Stegosaurus, and numerous other Jurassic giants that now form the backbone of the museum’s collection. The museum’s scientists developed pioneering techniques for excavating, preserving, and mounting these massive specimens, many of which remain on display in their original early 20th-century configurations. The Carnegie Museum’s Morrison Formation collection remains among the most scientifically valuable in the world, containing numerous type specimens that serve as the reference point for defining entire dinosaur species, giving Pittsburgh an authoritative voice in how we classify and understand these ancient creatures.

Dinosaur Hall: An Evolving Exhibition

The Carnegie Museum’s Dinosaur Hall represents one of America’s oldest continuously operating dinosaur exhibitions, evolving over more than a century to reflect changing scientific understanding while maintaining its historic character. The hall’s current configuration showcases both the scientific content and the cultural history of dinosaur paleontology, with specimens mounted in scientifically accurate postures while preserving the aesthetic of early 20th-century museum practices. Visitors can witness the famous “stance controversy” illustrated through different mounting techniques that show how our understanding of dinosaur posture has evolved from dragging-tailed reptiles to dynamic, active creatures. The exhibition uniquely features specimens in various states of preparation, from articulated skeletons to partially prepared fossils still embedded in their matrix, providing insight into the painstaking work of fossil preparation. Recent renovations have incorporated digital technologies and interactive elements while respecting the hall’s historic significance, creating a space where visitors can appreciate both the dinosaurs themselves and Pittsburgh’s role in bringing them to the public’s attention.

PaleoLab: Where Science Meets Public View

One of the most innovative features of Pittsburgh’s dinosaur legacy is the Carnegie Museum’s PaleoLab, a working fossil preparation laboratory visible to museum visitors. Unlike traditional museum displays where only finished specimens are shown, the PaleoLab allows visitors to witness the meticulous process of freeing dinosaur bones from their surrounding rock matrix in real time. Professional preparators work behind glass walls using tools ranging from traditional dental picks to modern air-powered micro-jackhammers, demonstrating the blend of artistry and science required to reveal fossils without damaging them. The lab processes specimens from ongoing Carnegie expeditions as well as historic collections that require conservation or remounting based on new scientific information. Interpretive staff regularly engage with visitors to explain the techniques being used and the significance of the specimens being prepared, making the scientific process transparent to the public. This behind-the-scenes access has inspired countless young visitors to pursue careers in paleontology, extending Pittsburgh’s dinosaur legacy to new generations of researchers.

The Scientific Legacy: Research Beyond Display

While the public primarily associates Pittsburgh’s dinosaur connection with spectacular mounted skeletons, the scientific research conducted at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History forms an equally important aspect of the city’s paleontological legacy. The museum maintains one of North America’s most active vertebrate paleontology research departments, with scientists continuing the fieldwork tradition established by Carnegie over a century ago. Current research projects range from describing new dinosaur species to analyzing growth patterns in fossil bones and investigating mass extinction events. The museum’s Section of Vertebrate Paleontology publishes dozens of peer-reviewed scientific papers annually, contributing significantly to our understanding of dinosaur evolution, behavior, and ecology. The institution’s massive collection of type specimens—the reference fossils that define particular species—makes Pittsburgh an essential research destination for paleontologists worldwide who must examine these definitive examples when classifying discoveries. This ongoing scientific productivity ensures Pittsburgh remains not just a place to view dinosaurs but a center for creating new knowledge about Earth’s prehistoric past.

Dinosaurs in Pittsburgh’s Cultural Identity

Dinosaurs have become woven into Pittsburgh’s cultural fabric in ways that extend far beyond the museum walls, creating a unique element of the city’s identity. Local businesses incorporate dinosaur themes into their names and logos, most notably the Pittsburgh-based Carnegie Mellon University’s “Tartan” mascot, which is frequently depicted alongside dinosaur imagery in recognition of the Carnegie connection. Annual events like “Jurassic Pittsburgh” bring dinosaur-themed activities to neighborhoods throughout the city, while the museum’s dinosaur replicas regularly appear in parades and civic celebrations. Public art installations featuring dinosaur motifs can be found throughout Pittsburgh, from playground equipment to corporate lobby sculptures, reflecting the creatures’ significance to the community’s self-image. The dinosaur connection even extends to Pittsburgh’s sports culture, with informal dinosaur mascots occasionally appearing alongside the official team symbols of the Steelers, Pirates, and Penguins during championship celebrations. This cultural integration demonstrates how thoroughly the dinosaur legacy established by Andrew Carnegie has been embraced as a distinctive element of Pittsburgh’s character, distinguishing it from other industrial cities of the American Midwest.

Field Expeditions: From Wyoming to Antarctica

The tradition of Carnegie-sponsored dinosaur expeditions that began in the late 19th century continues today, with Pittsburgh-based paleontologists conducting fieldwork across the globe. Modern Carnegie expeditions utilize advanced technologies like ground-penetrating radar and photogrammetry alongside traditional excavation techniques, yet maintain the meticulous documentation standards established by the museum’s early fossil hunters. Recent decades have seen Carnegie teams working in Madagascar, where they discovered several previously unknown dinosaur species that have revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur evolution in the southern hemisphere. Particularly significant are the museum’s ongoing excavations in the Cretaceous formations of Utah and Montana, which have yielded specimens that help bridge evolutionary gaps in the dinosaur family tree. Perhaps most ambitious are the Carnegie Museum’s participation in expeditions to Antarctica, where researchers brave extreme conditions to recover fossils that provide crucial evidence about dinosaur adaptation to polar environments and continental drift. These continuing field programs ensure a steady flow of new specimens to Pittsburgh, maintaining the city’s relevance in contemporary paleontological research.

Digital Dinosaurs: Technology and Pittsburgh’s Fossil Heritage

The Carnegie Museum has embraced cutting-edge digital technologies to study, preserve, and share Pittsburgh’s dinosaur treasures with audiences worldwide. High-resolution 3D scanning projects have created detailed digital models of key specimens in the collection, allowing researchers to study fossil morphology without physically handling fragile bones and enabling precise comparisons between specimens housed in different institutions. The museum’s online digital collections database makes information about thousands of specimens accessible to researchers and dinosaur enthusiasts globally, extending Pittsburgh’s influence far beyond physical visitors to the museum. Virtual reality experiences developed by the museum’s digital team allow visitors to “interact” with dinosaurs in their prehistoric environments, based on the latest scientific understanding of how these animals lived and moved. Particularly innovative is the museum’s use of CT scanning technology to examine the internal structure of fossils without damaging them, revealing details about dinosaur biology that would remain hidden using traditional research methods. These digital initiatives represent the evolution of Andrew Carnegie’s original vision of making Pittsburgh’s dinosaur resources accessible to the widest possible audience.

Local Fossil Sites: Pennsylvania’s Own Prehistoric Past

While the Carnegie Museum is best known for its dinosaur specimens from the American West, Pittsburgh’s status as a fossil hotspot is reinforced by significant paleontological sites within Pennsylvania itself. The region’s rich coal deposits preserve extensive fossils from the Carboniferous period, some 300 million years ago, when western Pennsylvania was covered by vast swampy forests populated by giant amphibians and early reptiles that predated dinosaurs. Carnegie researchers have documented several important fossil sites in the surrounding counties, including the famous Redstone Quarry, which has yielded exceptionally preserved plant fossils that help reconstruct the prehistoric environments of the region. Although true dinosaur fossils are rare in Pennsylvania due to geological factors, the state has produced significant specimens of other prehistoric creatures, including the giant prehistoric ground sloth Megalonyx jeffersonii, first described by Thomas Jefferson and now studied extensively by Carnegie paleontologists. The museum maintains active excavation programs at several Pennsylvania sites, engaging local volunteers and creating opportunities for residents to participate directly in uncovering the region’s fossil heritage.

Education Programs: Nurturing Future Paleontologists

Pittsburgh’s dinosaur legacy continues through robust educational programs that inspire the next generation of paleontologists and fossil enthusiasts. The Carnegie Museum offers specialized workshops where children and adults can learn fossil preparation techniques under expert guidance, working with actual specimens from the museum’s teaching collection. The institution’s Paleontological Field Programs allow high school students and adult amateurs to participate in actual dinosaur digs in Wyoming and Montana, creating hands-on experiences that go far beyond typical museum education. Particularly innovative is the museum’s “Paleo Passport” program, which creates a structured curriculum for aspiring young paleontologists to develop increasingly sophisticated skills and knowledge about fossils. The museum also partners with the University of Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University to offer college-level courses in paleontology, utilizing the museum collections as teaching resources and providing opportunities for undergraduate research projects. These educational initiatives ensure Pittsburgh’s dinosaur expertise is transmitted to new generations who will continue the scientific legacy established by Carnegie over a century ago.

Future Excavations: Pittsburgh’s Ongoing Dinosaur Quest

The search for new dinosaur specimens continues to drive Pittsburgh’s paleontological community forward, with ambitious plans for future excavations that will expand the city’s fossil legacy. The Carnegie Museum has recently secured permits for new excavation sites in previously unexplored regions of the Morrison Formation, targeting areas predicted to contain specimens that could fill important gaps in our understanding of Jurassic ecosystems. Particularly exciting are the museum’s planned expeditions to the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, following in the footsteps of the famous Roy Chapman Andrews expeditions but using modern techniques to locate fossil-bearing deposits. Museum scientists are also developing new partnerships with institutions in Argentina to explore the rich dinosaur deposits of Patagonia, which contain unique southern hemisphere species that evolved separately from their northern counterparts. These future excavations rely on a combination of traditional field techniques and cutting-edge technologies like drone-based aerial surveys and AI-assisted fossil identification systems developed in partnership with Pittsburgh’s technology sector. The continued investment in field exploration ensures that Pittsburgh will remain at the forefront of dinosaur discoveries well into the 21st century, building upon the foundation laid by Andrew Carnegie’s original vision.

Conclusion

Andrew Carnegie’s passion for dinosaurs transformed an industrial steel town into an unexpected paleontological powerhouse that continues to influence our understanding of prehistoric life. From the iconic Diplodocus carnegii that became a global ambassador to cutting-edge research and education programs, Pittsburgh’s dinosaur connection has evolved far beyond mere museum displays into a comprehensive scientific and cultural legacy. As the Carnegie Museum of Natural History continues its tradition of fieldwork, research, and public engagement, Pittsburgh maintains its status as a genuine fossil hotspot that bridges the gap between industrial heritage and natural history, creating a unique identity that distinguishes it among American cities. This enduring dinosaur legacy stands as perhaps the most unexpected yet enduring contribution of the Steel City to world culture and scientific knowledge.