The Alberta Badlands stand as one of North America’s most remarkable geological treasures, a landscape where time itself seems carved into the earth. Stretching across southeastern Alberta, Canada, this otherworldly terrain of hoodoos, coulees, and stratified cliffs has yielded some of the most significant paleontological discoveries in history. The region’s unique combination of ancient sedimentary deposits, erosional processes, and fortuitous preservation conditions has created what scientists consider a fossil paradise. From the magnificent Tyrannosaurus rex to the three-horned Triceratops, the Alberta Badlands have revealed countless secrets about life during the Late Cretaceous period, offering an unparalleled window into Earth’s distant past and establishing the region as one of the world’s premier fossil destinations.

The Geological Formation of the Alberta Badlands

The Alberta Badlands weren’t always the rugged, eroded landscape we see today – their story begins approximately 70-75 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous period. At that time, the region was submerged beneath the Western Interior Seaway, a vast inland sea that split North America into eastern and western landmasses. As this ancient sea retreated, it deposited layers of sediment that would eventually form the foundation of the Badlands. The dramatic transformation into today’s landscape began in earnest about 15,000 years ago as the last ice age ended. Massive glacial meltwaters carved through the soft sedimentary rock, creating deep valleys and exposing the distinct layered formations we see today. This rapid erosional process continues even now, with wind and water gradually revealing new fossil material each year as the landscape constantly transforms.

The Perfect Conditions for Fossil Preservation

The Alberta Badlands represent a perfect storm of conditions for exceptional fossil preservation. During the Late Cretaceous period, the region featured lush coastal plains and river deltas that supported abundant plant and animal life, including numerous dinosaur species. When organisms died, many were quickly buried by sediment in river channels, floodplains, or coastal areas, protecting them from scavengers and decomposition. The region’s fine-grained sediments proved ideal for preserving even delicate structures like feathers and skin impressions. Additionally, the relatively stable geological history of the area meant that once buried, many fossils remained undisturbed for millions of years. Perhaps most crucially, the Badlands’ arid modern climate and rapid erosion continuously exposes new fossil material without the heavy vegetation that might conceal specimens in more humid regions, creating a natural laboratory where paleontologists can literally watch as new discoveries emerge from the earth.

Dinosaur Provincial Park: A UNESCO World Heritage Site

Designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979, Dinosaur Provincial Park represents the crown jewel of the Alberta Badlands’ paleontological treasures. Spanning approximately 80 square kilometers along the Red Deer River, this protected area contains some of the richest dinosaur fossil deposits on Earth. The park has yielded remains from over 44 dinosaur species, with more than 500 specimens removed for scientific study and museum display around the world. What makes the park particularly remarkable is the density of fossils – in some areas, researchers can find dozens of specimens within a single square kilometer. The site offers a rare snapshot of a complete Late Cretaceous ecosystem, preserving not just dinosaurs but also ancient turtles, crocodilians, mammals, and plant material. For visitors, the park provides guided tours where paleontologists explain ongoing excavations and the significance of this extraordinary location where new discoveries continue to emerge nearly 150 years after the first documented fossil finds in the region.

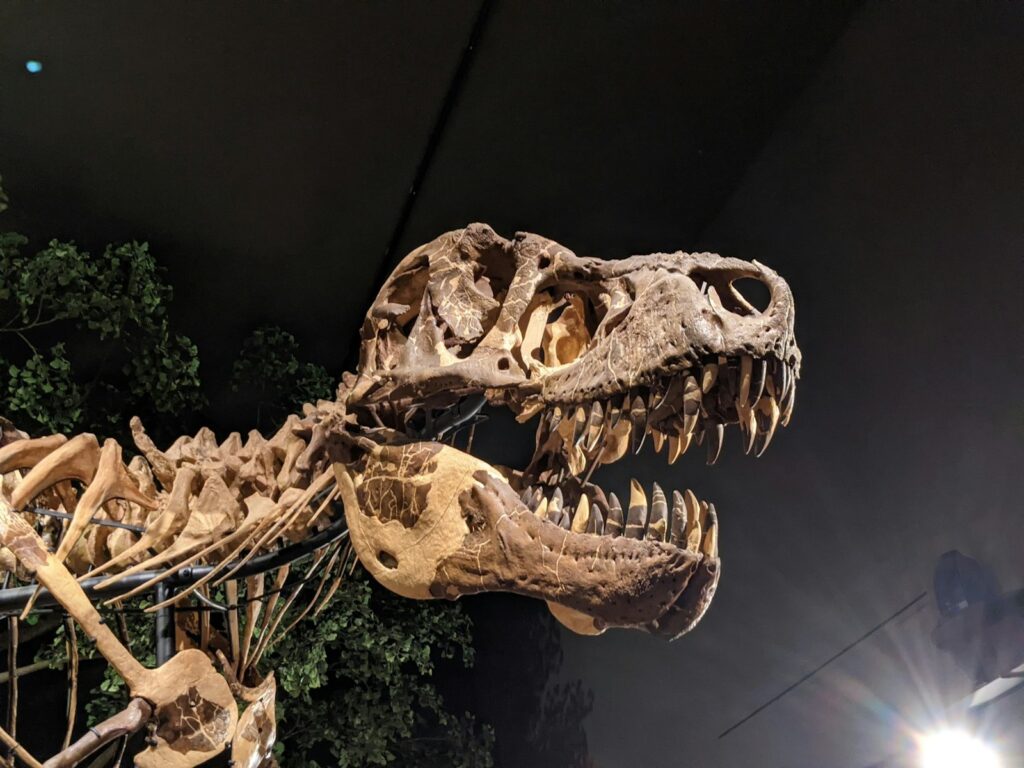

The Royal Tyrrell Museum: Showcasing Alberta’s Fossil Legacy

Located in Drumheller, the heart of the Alberta Badlands, the Royal Tyrrell Museum stands as Canada’s premier paleontological institution and a testament to the region’s extraordinary fossil wealth. Named after Joseph Burr Tyrrell, who discovered the first dinosaur remains in the area in 1884, the museum houses one of the world’s largest displays of dinosaurs with over 160,000 cataloged specimens. The facility combines cutting-edge research laboratories with public exhibitions that bring the ancient world to life through innovative displays and reconstructions. Beyond mere exhibition, the museum serves as an active research center where scientists prepare and study new discoveries, often working in laboratories visible to visitors. The Royal Tyrrell’s “Preparation Lab” allows guests to observe technicians meticulously freeing fossils from surrounding rock matrix, while the “Dinosaur Hall” features more than 40 mounted dinosaur skeletons, including “Black Beauty,” one of the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex specimens ever discovered, which emerged from the Badlands in 1980.

Famous Dinosaur Discoveries in the Badlands

The Alberta Badlands have produced some of paleontology’s most significant dinosaur discoveries, fundamentally reshaping our understanding of these ancient creatures. In 1910, American paleontologist Barnum Brown unearthed the first substantially complete Albertosaurus skeleton, a slightly smaller relative of Tyrannosaurus rex that would later become emblematic of Alberta’s fossil heritage. The region has yielded exceptional specimens of horned dinosaurs, including numerous Centrosaurus bone beds that suggest these animals died in massive herds during flooding events. Perhaps most spectacular was the 1980 discovery of “Black Beauty,” a remarkably preserved Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton with nearly 85% of its bones intact, including rare skull material. In more recent years, the 2010 identification of Regaliceratops peterhewsi, nicknamed “Hellboy” for its difficult excavation, represented an entirely new genus of horned dinosaur with a distinctive frill pattern. These discoveries continue to emerge from the Badlands’ eroding slopes, with each new find potentially rewriting what we know about dinosaur evolution, behavior, and ecosystems.

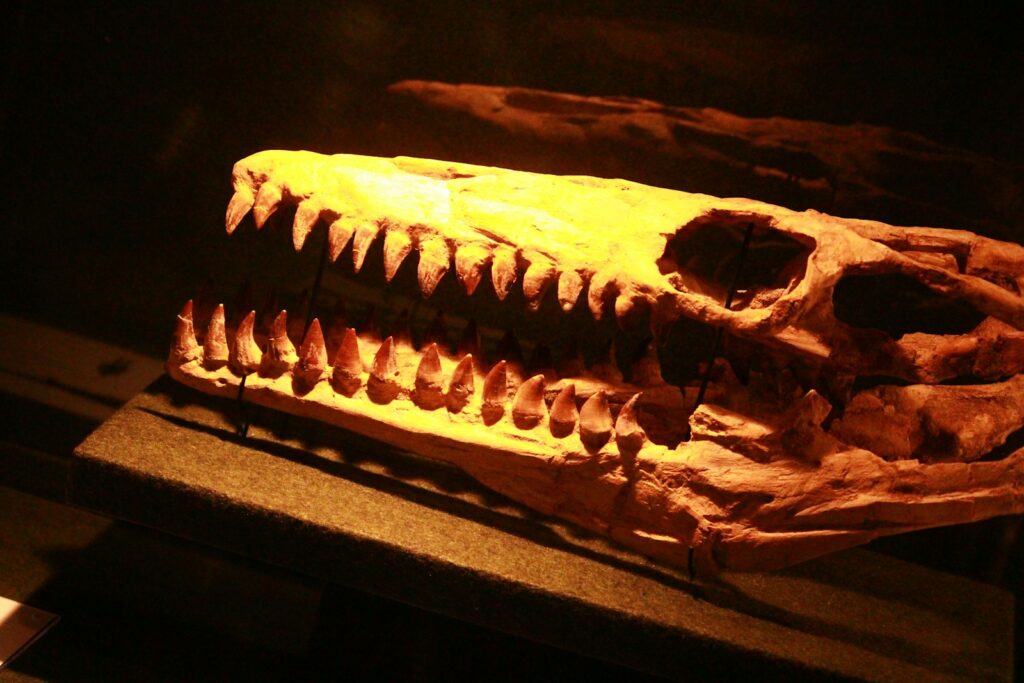

Beyond Dinosaurs: The Diversity of Badlands Fossils

While dinosaurs capture the public imagination, the Alberta Badlands preserve a much broader spectrum of ancient life that creates a comprehensive picture of Late Cretaceous ecosystems. The region has yielded exceptional specimens of prehistoric turtles, including Basilemys, a land-dwelling tortoise the size of a coffee table that roamed alongside dinosaurs. Aquatic environments are represented by fossils of champsosaurs (crocodile-like reptiles), bowfins, gars, and other fish species that inhabited ancient rivers and coastal waters. Remarkably preserved plant fossils document ancient forests of metasequoia, magnolia, and palm-like cycads that once thrived in Alberta’s formerly subtropical climate. Even small, fragile specimens rarely preserved elsewhere have been found, including early mammals no larger than modern shrews, delicate dragonfly wings, and even coprolites (fossilized feces) that provide insights into ancient diets. This extraordinary diversity creates a rare opportunity for scientists to reconstruct entire prehistoric food webs and understand the complex ecological relationships that shaped life during the twilight of the dinosaur era.

The Mystery of the K-T Boundary

The Alberta Badlands hold particular scientific significance due to their preservation of the Cretaceous-Tertiary (K-T) boundary, the geological layer marking the mass extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs approximately 66 million years ago. In certain locations within the Badlands, researchers can literally place their finger on the thin, clay-rich layer containing elevated levels of iridium – an element rare on Earth but abundant in asteroids – supporting the theory that a massive impact triggered this extinction event. Above this boundary, dinosaur fossils abruptly disappear from the geological record, while mammal fossils become increasingly common, documenting the dramatic ecological shift that followed. The Badlands’ extensive exposure of rocks spanning both before and after this catastrophic event provides scientists with valuable insights into how ecosystems collapsed and subsequently recovered. Ongoing research in the region continues to refine our understanding of extinction dynamics, including whether dinosaurs were already in decline before the asteroid impact or if they remained thriving until their sudden demise.

The Science of Fossil Hunting in the Badlands

Fossil hunting in the Alberta Badlands combines meticulous science with a dash of wilderness adventure, requiring specialized techniques adapted to the region’s unique conditions. Paleontologists typically begin their search during spring and summer when winter erosion has exposed new material but before summer storms can damage freshly revealed specimens. The process often starts with prospecting – systematically scanning exposed hillsides for bone fragments that might indicate larger specimens nearby. When promising material is identified, researchers carefully remove the overburden (overlying rock and soil) using tools ranging from bulldozers for large-scale operations to dental picks for delicate specimens. Most fossils emerge encased in a protective plaster jacket to prevent damage during transport to laboratory facilities. The region’s bentonite clay, which expands when wet and contracts when dry, presents particular challenges as it can quickly fracture fossils exposed to the elements. Consequently, many expeditions operate under time pressure, racing to recover specimens before natural weathering processes destroy them, adding urgency to the scientific endeavor.

The Hoodoos: Sentinels of Geological Time

The Alberta Badlands’ most iconic features, the towering hoodoos, serve as both striking landmarks and important geological indicators of the processes that make this region a fossil treasury. These distinctive pillars, typically standing 5-7 meters tall, form when erosion-resistant capstones of harder sandstone protect columns of softer sedimentary rock beneath them from rainfall and weathering. As surrounding material gradually washes away, these sentinel-like formations emerge from the landscape, often revealing fossil material in their stratified layers. Each hoodoo represents millions of years of geological history, with distinct bands of color indicating different depositional environments and time periods. The most famous collection near Drumheller showcases the Horseshoe Canyon Formation, deposited approximately 70-73 million years ago when the region alternated between coastal plains and shallow seas. Though striking in their permanence, hoodoos are actually temporary features on a geological timescale – eventually, even their protective caps will erode, causing their collapse and continuing the cycle of exposure that makes the Badlands such productive fossil hunting grounds.

The Role of Amateur Fossil Hunters

Amateur fossil enthusiasts have played a crucial role in the exploration and discovery of the Alberta Badlands’ paleontological treasures, often making finds that might otherwise remain hidden. In 1884, Joseph Burr Tyrrell, a geologist primarily searching for coal deposits, made the region’s first documented dinosaur discovery – a partial Albertosaurus skull that would eventually help establish Alberta’s reputation for exceptional fossils. More recently, in 2010, commercial fossil hunter Wendy Sloboda spotted unusual bones protruding from a riverbank that led to the discovery of Regaliceratops, an entirely new genus of horned dinosaur. While Alberta strictly regulates fossil collection – all vertebrate fossils legally belong to the province – authorities have created programs that harness amateur enthusiasm while protecting scientific resources. The Royal Tyrrell Museum’s “Day Digs” and guided excavations allow visitors to participate in actual fieldwork under professional supervision, while their “Fossil Finder” program encourages hikers to photograph and report potential discoveries without removing specimens. These collaborative approaches have significantly expanded the reach of formal paleontological efforts while fostering public appreciation for the scientific importance of the region’s natural heritage.

Climate Change and the Future of Badlands Fossils

The very erosional processes that make the Alberta Badlands such a productive fossil region also create vulnerabilities in the face of climate change. Scientists have documented increasing weather extremes in the region, with more frequent intense rainfall events accelerating erosion in some areas. This double-edged phenomenon can expose new fossils but also potentially damage specimens before they can be discovered and properly excavated. Rising temperatures have extended the annual field season but also increased the risk of rapid weathering for newly exposed fossils. Conservation paleontologists now employ advanced mapping technologies, including LiDAR and drone surveys, to monitor high-potential fossil sites for emerging specimens that might require urgent recovery. Some research teams have begun implementing erosion control measures around particularly significant discoveries that cannot be immediately excavated. The changing climate also affects the Badlands’ vegetation patterns, with some areas experiencing increased plant growth that could potentially obscure fossil-bearing exposures that have traditionally remained bare. These evolving conditions have prompted paleontological institutions to develop new strategies for systematic monitoring and prioritized excavation to ensure that irreplaceable specimens aren’t lost to accelerating environmental changes.

Tourism and Education in the Badlands

The Alberta Badlands have transformed from remote badlands to international tourism destination largely because of their extraordinary fossil heritage. Approximately 400,000 visitors annually travel to Drumheller and the surrounding region specifically for paleontological attractions, generating significant economic activity for local communities. Beyond the Royal Tyrrell Museum, the region offers numerous educational experiences, including the self-guided Dinosaur Trail driving route that showcases geological formations spanning millions of years. For those seeking hands-on experiences, several outfitters offer guided fossil hunting excursions where visitors can search for (though not collect) vertebrate fossils while learning about identification and documentation techniques. The World’s Largest Dinosaur, a 26-meter tall Tyrannosaurus rex statue in Drumheller, has become an unlikely ambassador for paleontological education, drawing families who then engage with more substantive scientific content. Educational programs have expanded to include virtual options, with the Royal Tyrrell Museum’s distance learning initiatives reaching over 10,000 students annually across North America. This blend of tourism and education has created a unique environment where entertainment seamlessly integrates with scientific learning, making complex paleontological concepts accessible to visitors of all ages.

Preserving the Badlands for Future Generations

The scientific importance of the Alberta Badlands has prompted comprehensive conservation efforts to balance research access with long-term preservation. Alberta’s Historical Resources Act provides strong legal protection for paleontological resources, making it illegal to collect vertebrate fossils without proper permits and ensuring significant discoveries remain within public institutions. Dinosaur Provincial Park employs a dual management approach with strictly protected “Preservation Zones” accessible only to researchers with permits, alongside “Public Zones” where visitors can experience the landscape while minimizing impact on fossil resources. Conservation officials conduct regular monitoring of erosion patterns and fossil exposure using both traditional field surveys and emerging technologies like aerial photogrammetry to identify priority areas for scientific intervention. Local communities have increasingly embraced their role as stewards of this natural heritage, with ranchers and landowners participating in reporting programs that alert authorities when significant fossils appear on private lands. These multifaceted conservation efforts aim to ensure that the Alberta Badlands continue revealing their prehistoric secrets for generations to come, maintaining the delicate balance between scientific discovery and environmental protection in this remarkable landscape where the past literally emerges from the earth.

Conclusion

The Alberta Badlands represent a rare confluence of geological processes, preservation conditions, and modern accessibility that has created one of Earth’s most significant windows into prehistoric life. From towering museum displays to ongoing field discoveries, the region continues to expand our understanding of the Late Cretaceous world. As erosional forces constantly reshape this dramatic landscape, new fossils emerge annually, promising future revelations about ancient ecosystems and extinct creatures. The scientific importance of these finds extends far beyond mere curiosity about dinosaurs – they provide crucial insights into evolution, extinction dynamics, and ecosystem responses to environmental change, offering potential lessons relevant to our own era of climate uncertainty. Through careful management balancing research, education, and conservation, the Alberta Badlands stand as both a natural laboratory for paleontologists and an extraordinary destination where visitors can experience the tangible evidence of Earth’s deep history, preserved in stone and continuing to emerge from this remarkable fossil goldmine.