In the world of paleontology, the discovery of ancient fossils represents more than just scientific advancement—it often ignites passionate disputes over ownership, cultural heritage, and academic prestige. These “fossil feuds” have shaped museum collections worldwide and continue to influence how we preserve and display our planet’s prehistoric past. From multimillion-dollar dinosaur skeletons to ancient human remains, the question of who rightfully owns these irreplaceable artifacts frequently pits institutions, countries, and indigenous communities against one another in complex legal and ethical battles. This article explores the fascinating and often contentious world of fossil ownership disputes, examining the historical context, modern legal frameworks, and the evolving perspectives on who should ultimately have custody of Earth’s ancient treasures.

The Historical Context of Fossil Collection

The practice of collecting fossils for institutional display dates back to the early 19th century, when museums began assembling natural history collections as symbols of national pride and scientific advancement. During this colonial era, Western institutions frequently removed fossils from their countries of origin with little regard for local claims or interests. The famous “Bone Wars” of the late 1800s between American paleontologists Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh exemplified the competitive, often unethical tactics employed in early fossil hunting. These rivals destroyed specimens, bribed workers, and sabotaged each other’s dig sites in their quest for dinosaur discoveries. This historical foundation of fossil acquisition, often marked by exploitation and opportunism, continues to influence modern disputes as countries and communities increasingly question the legitimacy of collections acquired during colonial periods.

Legal Frameworks Governing Fossil Ownership

Today’s fossil disputes unfold within a complex patchwork of national and international laws that vary dramatically across jurisdictions. The United States treats fossils found on private land as the property of the landowner, creating a robust commercial market, while fossils discovered on federal lands belong to the public and must remain in the public trust. Countries like Argentina, Mongolia, and China have enacted strict laws declaring all fossils national property, prohibiting their export regardless of how they were discovered. International agreements like the 1970 UNESCO Convention on Cultural Property provide some framework for resolving cross-border disputes, but enforcement remains challenging. The legal landscape is further complicated by the fact that many museum specimens were acquired before current laws existed, raising questions about retroactive application of modern ethical standards to historical acquisitions.

The Tyrannosaur Named Sue: A Landmark Case

Perhaps no fossil dispute better illustrates the complexity of ownership claims than the case of Sue, the most complete Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever discovered. Unearthed in 1990 on a South Dakota ranch, Sue became the center of an intense legal battle involving the fossil hunter who discovered her, the landowner, the Sioux tribe who claimed ancestral rights to the land, and the federal government. The FBI eventually seized the skeleton, claiming it had been illegally removed from federal land. After years of litigation, the court ruled that Sue belonged to the landowner, who subsequently sold her at auction for $8.36 million to Chicago’s Field Museum. This unprecedented price tag transformed the fossil market and highlighted the tension between scientific access and commercial interests. Sue’s case established legal precedents that continue to influence fossil ownership disputes today, particularly regarding the rights of private landowners versus scientific institutions.

Repatriation Demands and National Heritage

In recent decades, countries with rich fossil deposits have increasingly demanded the return of specimens housed in foreign museums, viewing these artifacts as integral to their national heritage. Mongolia’s successful campaign to recover numerous dinosaur specimens, including a nearly complete Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton that had been sold at a New York auction for over $1 million, represents a watershed moment in these repatriation efforts. The Mongolian government argued that the specimen had been illegally exported, as all fossils found within Mongolia’s borders legally belong to the state. Similar repatriation claims have emerged from Argentina, China, and Morocco, challenging museums to justify their possession of specimens acquired through previously accepted but now questionable practices. These demands force institutions to confront difficult questions about the origins of their collections and whether historical acquisition methods meet contemporary ethical standards.

Indigenous Perspectives on Ancestral Remains

For indigenous communities worldwide, fossil disputes often transcend scientific and legal considerations, touching on profound spiritual and cultural dimensions. Human remains and artifacts associated with ancestral peoples represent not merely scientific specimens but sacred entities deserving of respectful treatment according to traditional practices. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) in the United States established a legal framework requiring federally-funded institutions to return Native American cultural items and human remains to their descendant communities. Similar legislation has emerged in Australia regarding Aboriginal remains and in New Zealand concerning Māori ancestors. These perspectives challenge the traditional museum approach of displaying human remains as scientific specimens, suggesting that cultural and spiritual considerations may sometimes outweigh research interests. When museums resist repatriation claims, citing scientific importance, deeply emotional conflicts can ensue that reveal fundamentally different worldviews regarding human remains.

Commercial Fossil Markets versus Scientific Access

A central tension in many fossil disputes involves the growing commercial market for specimens and its impact on scientific research. Private collectors willing to pay millions for premium specimens can outbid museums and research institutions, potentially placing scientifically valuable fossils beyond the reach of researchers. The controversial sale of the dinosaur “Dueling Dinosaurs” for $6 million illustrates this dilemma, as paleontologists worried that this important specimen showing what appears to be a predator and prey preserved together might disappear into a private collection. On the other hand, commercial fossil hunting has led to many important discoveries that might otherwise remain buried, and some private collectors collaborate extensively with scientists. Museums increasingly find themselves navigating this complex landscape, sometimes partnering with private collectors or wealthy donors to secure important specimens that would otherwise be financially unattainable, raising questions about whether scientific knowledge should be determined by financial resources.

Digital Technology and Shared Access Solutions

As ownership disputes continue, digital technologies offer potential compromises that could transform how we think about fossil access and preservation. Advanced 3D scanning and printing technologies now allow museums to create highly detailed replicas of fossils that can be shared across institutions worldwide without transferring physical ownership. The African Fossils Virtual Laboratory project, for instance, has created digital models of important hominin fossils from East Africa, making these specimens virtually accessible to researchers globally while the originals remain in their countries of origin. These technologies suggest a future where the physical location of a specimen might become less important than ensuring widespread digital access to its scientific data. Some institutions have begun exploring blockchain technology to create verifiable digital records of provenance and ownership, potentially reducing disputes over specimen origins while facilitating appropriate sharing of scientific information across national boundaries.

The Ethics of Fossil Collecting in Developing Nations

Fossil disputes often reflect broader economic inequalities between wealthy institutions and fossil-rich regions with limited resources for excavation and preservation. Countries like Morocco, Peru, and Mongolia possess extraordinary fossil deposits but may lack the infrastructure to properly excavate, study, and display these finds, creating incentives for local collectors to sell specimens abroad despite export restrictions. Some museums have addressed this imbalance by developing collaborative partnerships with institutions in source countries, providing training, equipment, and funding while ensuring that significant discoveries remain in or return to their countries of origin. The American Museum of Natural History’s partnership with the Mongolian Academy of Sciences exemplifies this approach, combining expertise and resources while respecting Mongolia’s legal claim to its paleontological heritage. These collaborations acknowledge that fossil ownership involves not just possession but responsibility for proper conservation, study, and public education.

When Museums Compete: Institutional Rivalries

Competition between museums for prestigious specimens has historically driven many fossil disputes, with institutions vying for the biggest, most complete, or most scientifically significant examples. The rivalry between Canadian museums over ownership of the “Tumbler Ridge dinosaur trackways,” a series of remarkable dinosaur footprints discovered in British Columbia, demonstrates how even institutions within the same country can become embroiled in bitter ownership conflicts. Similarly, multiple American museums competed intensely for “Scotty,” one of the largest T. rex specimens ever found, with each institution claiming they could provide superior conservation and public access. These institutional rivalries often reflect broader competition for visitors, prestige, and funding in the museum world. As public funding for museums has declined in many countries, the pressure to attract visitors with spectacular displays has intensified, sometimes prioritizing spectacular specimens over comprehensive collections and potentially compromising scientific cooperation.

The Impact of Social Media on Fossil Disputes

The advent of social media has dramatically changed how fossil disputes unfold, bringing previously obscure academic and legal battles into the public sphere. When Brazil demanded the return of a rare pterosaur fossil from a German museum in 2020, the dispute quickly generated international attention through Twitter campaigns and online petitions, putting public pressure on institutions in ways impossible in previous decades. Hashtag campaigns like #ReturnOurBones have united indigenous communities across continents in demanding repatriation of ancestral remains, creating powerful advocacy networks that transcend geographical boundaries. Museums now face unprecedented public scrutiny regarding their acquisition practices, with social media users often investigating and publicizing questionable provenance information. This democratization of information has shifted power dynamics in fossil disputes, giving previously marginalized voices greater influence in debates over who should control prehistoric heritage while forcing institutions to respond more transparently to ownership controversies.

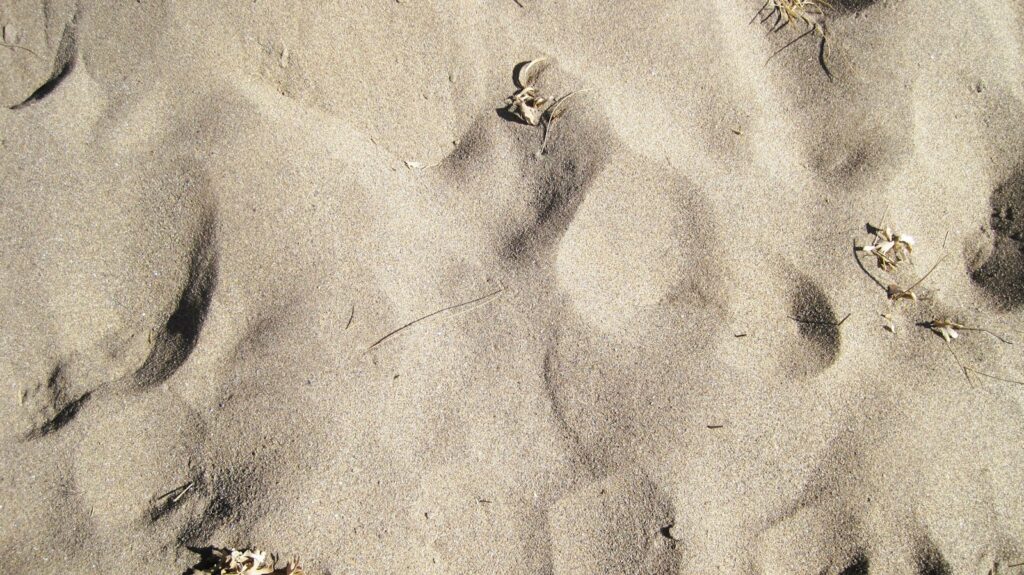

Case Study: The Mongolian Dinosaur Smuggling Ring

One of the most dramatic fossil ownership disputes of recent years involved an international smuggling network that illegally exported numerous dinosaur specimens from Mongolia’s Gobi Desert. The case began in 2012 when paleontologists noticed a Tarbosaurus bataar skeleton up for auction in New York that could only have come from Mongolia, where export of fossils is strictly prohibited. This discovery triggered a multi-year investigation revealing a sophisticated operation that had been smuggling fossils through multiple countries by falsifying documents and obscuring their origins. The investigation resulted in the repatriation of more than 30 dinosaur specimens to Mongolia and a prison sentence for commercial fossil dealer Eric Prokopi, who pleaded guilty to smuggling charges. This case highlighted the challenges of enforcing national ownership laws across international boundaries and the critical importance of museum due diligence in verifying the provenance of potential acquisitions. It also demonstrated how scientific expertise could be crucial in identifying illegally exported specimens, as the distinctive characteristics of the fossils provided key evidence of their Mongolian origin.

The Future of Fossil Ownership and Sharing

The landscape of fossil ownership continues to evolve rapidly, with new approaches emerging that may resolve long-standing disputes. Some experts advocate for a “scientific patrimony” model that recognizes fossils as part of humanity’s shared heritage while respecting the special relationship between specimens and their countries of origin. Under this framework, physical ownership might remain with the source country, but the scientific knowledge derived from fossils would be considered a global resource. International repositories or “fossil banks” could potentially provide neutral storage for disputed specimens while legal questions are resolved. The development of international standards for fossil acquisition and display, similar to existing protocols for art museums, could help prevent future disputes by establishing clear ethical guidelines that transcend national boundaries. As technological capabilities for creating and sharing digital specimens continue to advance, the concept of ownership itself may gradually shift from exclusive physical possession toward models of shared stewardship and global access to scientific information.

Conclusion: Balancing Science, Heritage, and Ethics

Fossil feuds between museums reflect deeper questions about how we value and share our planet’s prehistoric heritage. These disputes rarely have simple solutions, requiring careful balancing of scientific interests, national heritage claims, indigenous perspectives, and practical considerations of preservation capability. The most promising path forward appears to involve collaborative approaches that respect the legitimate interests of all stakeholders while prioritizing both scientific advancement and appropriate cultural respect. Museums increasingly recognize that building lasting relationships with source communities and countries serves their long-term interests better than clinging to disputed specimens acquired through questionable means. As our understanding of ethical collecting evolves, so too must our institutional practices and legal frameworks. Ultimately, the goal should be ensuring that Earth’s remarkable fossil record receives the study, protection, and appreciation it deserves, while acknowledging that these irreplaceable windows into our planet’s past belong in some sense to all of humanity—past, present, and future.