For millions of years, dinosaurs roamed the Earth as the dominant terrestrial vertebrates. While we’ve learned much about their anatomy, evolution, and extinction, some aspects of their daily lives remain shrouded in mystery. Among these enigmas is a seemingly simple question: How did dinosaurs sleep? Recent paleontological discoveries involving fossilized nests are providing fascinating new insights into dinosaur slumber patterns, parental care, and nocturnal behaviors. These findings help paint a more complete picture of how these magnificent creatures lived when they weren’t hunting, migrating, or engaging in other activities that often capture our imagination.

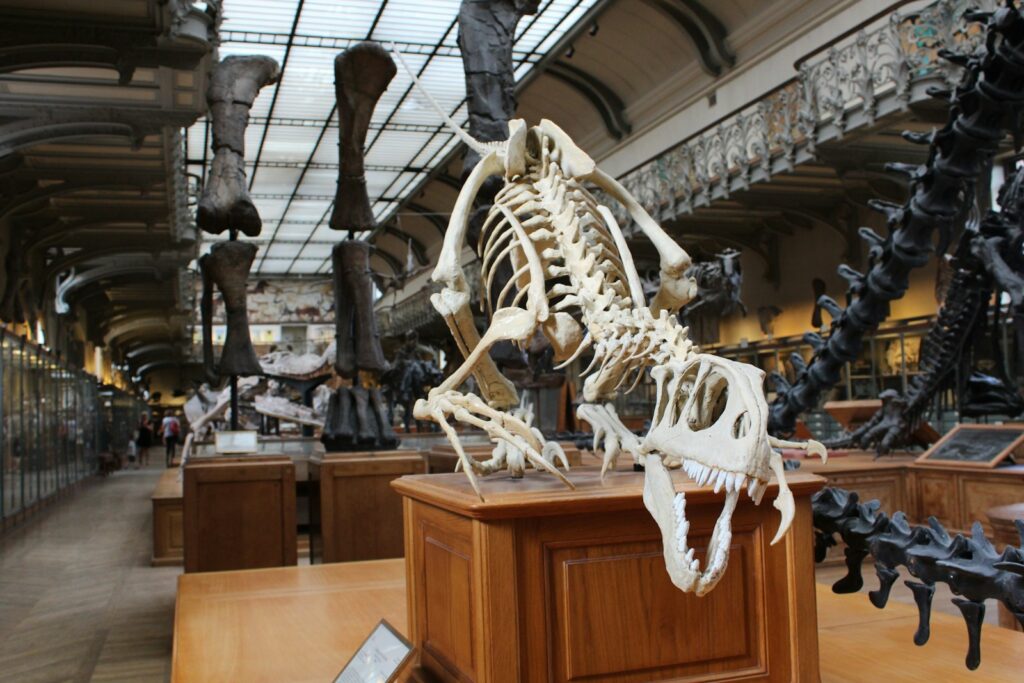

The Challenge of Studying Prehistoric Sleep

Image by Blond Fox, via Unsplash

Studying how extinct animals slept presents unique challenges for paleontologists since sleep doesn’t typically leave direct fossil evidence. Unlike bones, teeth, or even footprints, the act of sleeping doesn’t create preserved impressions in the fossil record that scientists can easily identify. Researchers must instead rely on indirect evidence, comparative anatomy with modern relatives, and rare fossil finds that capture dinosaurs in what appear to be resting positions.

Additionally, soft tissues like brains, which could provide clues about sleep cycles, rarely fossilize, forcing scientists to make careful inferences based on limited data. Despite these obstacles, paleontologists have developed innovative approaches to uncovering the sleeping habits of these ancient reptiles through careful analysis of fossilized nests, sleeping postures, and environmental contexts.

Remarkable Fossilized Nest Discoveries

Image by Adam Mathieu, via Unsplash

Fossilized nests represent some of the most information-rich discoveries for understanding dinosaur sleep patterns and parental behavior. In Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, paleontologists uncovered an Oviraptor specimen fossilized while apparently brooding its nest, suggesting a bird-like sleeping position over eggs. Another significant find in Argentina revealed multiple juvenile Mussaurus specimens nestled together in what appears to be a communal sleeping arrangement, indicating social sleeping behaviors similar to many modern birds.

Perhaps most remarkable was the discovery of a Mei long specimen in China’s Liaoning Province, preserved in what scientists call the “avian sleeping position” with its head tucked under its limb. These exceptional fossils provide rare glimpses into moments when dinosaurs were caught in sleeping or resting postures, offering direct evidence of their sleeping behaviors preserved for over 65 million years.

The Bird Connection: Clues from Modern Relatives

Image by David Valentine, via Unsplash

Birds, as the living descendants of theropod dinosaurs, provide crucial insights into potential dinosaur sleeping habits. Modern birds exhibit distinctive sleeping postures, with many tucking their heads under wings or limbs for warmth and protection while sleeping perched on branches. Neurological studies of birds reveal they experience both REM and non-REM sleep, sometimes even with unihemispheric sleep where one brain hemisphere remains alert while the other rests—a valuable adaptation for predator detection.

The discovery of dinosaur fossils in bird-like sleeping positions strongly suggests that some dinosaur species, particularly those most closely related to birds, may have slept in similar ways. This evolutionary connection allows paleontologists to make informed hypotheses about dinosaur sleep positions, brain activity during rest, and even the possibility that some dinosaurs may have slept in trees like many contemporary avian species.

Sleeping Postures Revealed Through Fossils

Image by Adam Mathieu, via Unsplash

Rare fossil specimens caught in sleeping positions have provided direct evidence of dinosaur resting postures. The most famous example is the small troodontid dinosaur Mei long, whose name appropriately means “soundly sleeping dragon” in Chinese. This remarkable specimen was preserved with its head tucked beneath its forearm and its tail curled around its body—strikingly similar to the sleeping posture of modern birds. Another notable example came from Montana, where a young Tyrannosaurus rex specimen named “Tinker” showed evidence of a resting position with limbs folded beneath its body.

The oviraptorid dinosaur Citipati was fossilized while apparently sitting on its nest with its limbs spread over the eggs in a protective posture, suggesting it may have slept in this position while incubating its offspring. These fossilized sleeping postures reveal not just how dinosaurs physically positioned themselves for rest, but also offer clues about their physiology and behavior.

Nesting Behaviors and Parental Care

Fossilized nests have transformed our understanding of dinosaur parental care and sleeping arrangements. Evidence from numerous sites worldwide indicates many dinosaur species created elaborate nests, sometimes in colonies, where adults would likely have slept while guarding their eggs. The discovery of adult Maiasaura specimens positioned near nests with worn tooth evidence suggests these “good mother lizards” remained with their nests for extended periods, potentially sleeping nearby while protecting their offspring.

Oviraptor nests show particularly compelling evidence, with adults fossilized directly atop nests in brooding positions, indicating they likely slept while incubating eggs similar to modern birds. These nesting sites also reveal that some dinosaur species, particularly ornithischians like Protoceratops, arranged their eggs in specific patterns within nests, suggesting sophisticated nesting behaviors that would have required extended periods of attentive care, including overnight presence and protection.

Communal vs. Solitary Sleeping Habits

Image by Amy-Leigh Barnard, via Unsplash

Fossil evidence increasingly suggests dinosaurs exhibited diverse sleeping arrangements ranging from solitary to highly social. Multiple juvenile specimens found together in what appear to be sleeping positions provide compelling evidence for communal sleeping in some species. The discovery of fifteen juvenile Mussaurus patagonicus specimens clustered together in Argentina suggests these young dinosaurs slept in groups, possibly for warmth or protection. Similarly, fossils of the small theropod Sinornithoides found in close proximity suggest pack sleeping behaviors.

In contrast, large predatory theropods like Tyrannosaurus rex likely slept alone as adults, based on their relatively solitary lifestyles and territorial behaviors inferred from fossil evidence. This diversity in sleeping arrangements mirrors the variety seen in modern animals, where sleeping habits often correlate with broader social structures, habitat requirements, and predator-prey relationships.

Sleep Adaptations for Different Dinosaur Body Types

Image by Narciso Arellano, via Unsplash

Dinosaur sleeping positions likely varied dramatically based on their diverse body plans and physical constraints. Massive sauropods like Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, with their enormous weight and long necks, may have slept standing up or leaning against trees, similar to how elephants sometimes rest. This hypothesis is supported by the biomechanical challenges these giants would have faced in lying down and standing back up repeatedly.

In contrast, with their quadrupedal stance and relatively low center of gravity, ceratopsians like Triceratops could likely rest on their sides or in a kneeling position without difficulty. Bipedal theropods such as Velociraptor probably slept in positions more reminiscent of modern birds, possibly with their heads tucked and limbs folded beneath them. These variations in sleeping postures reflect their skeletal anatomy and adaptations to their environment and predator-prey relationships.

Thermoregulation During Sleep

How dinosaurs managed body temperature during sleep provides fascinating insights into their physiology. Fossil evidence of dinosaurs sleeping in groups, particularly juveniles, suggests they may have huddled together for warmth during rest, similar to many modern birds and mammals. This behavior would be particularly important if dinosaurs possessed some degree of endothermy (warm-bloodedness) as current research increasingly suggests. Nest structures themselves often show evidence of materials that could provide insulation, with some fossilized nests containing remnants of vegetation that might have helped maintain egg and parent temperatures during overnight brooding.

For larger dinosaurs, their significant body mass would provide thermal inertia, helping them maintain relatively stable body temperatures through the night without dramatic cooling. The Mei long specimen’s bird-like sleeping posture, with limbs tucked close to the body and tail wrapped around, further suggests conservation of body heat was important during dinosaur sleep periods.

Nocturnal vs. Diurnal Dinosaurs

Image by Rafał Danhoffer, via Unsplash

Recent studies of dinosaur scleral rings—bones that surrounded their eyes—have provided compelling evidence about their daily activity patterns and how this might have influenced their sleeping habits. By comparing these structures with modern animals, researchers have determined that many dinosaur species were likely diurnal (active during daylight), making them predominantly nighttime sleepers.

However, some smaller theropods appear to have had adaptations for low-light vision, suggesting nocturnal or crepuscular (dawn and dusk) activity patterns, which would have required daytime sleeping adaptations. The small predator Velociraptor, for example, shows eye structures consistent with nocturnal hunting, suggesting it may have slept during daylight hours. This diversity in activity patterns indicates dinosaurs likely filled various ecological niches throughout the day and night, with sleeping patterns timed accordingly, similar to the varied sleep schedules seen in modern ecosystems.

The Sleep-Wake Cycle and Dinosaur Brains

Image by Tofan Teodor, via Unsplash

Understanding dinosaur sleep cycles requires examining what we know about their brain structures through endocasts—natural molds of their brain cavities. Though limited, this evidence suggests dinosaurs possessed brain regions analogous to those governing sleep in modern animals. Theropod dinosaurs, particularly those closely related to birds, had relatively large brains with developed visual processing centers, suggesting sophisticated sensory processing that would require restorative sleep.

Some research indicates dinosaurs likely experienced sleep cycles similar to their modern relatives, potentially including both REM and non-REM sleep phases. The brain size relative to body mass in many dinosaur species suggests they required regular sleep for cognitive function, similar to both reptiles and birds today. However, the exact nature of dinosaur sleep neurologically remains speculative due to the limitations of the fossil record in preserving soft tissue structures.

Predator-Prey Dynamics and Sleep Vulnerability

Sleep represents a period of vulnerability for any animal, and dinosaurs would have faced significant predation risks while resting. Fossil evidence suggests many dinosaur species developed strategies to minimize these risks, including sleeping in groups where multiple individuals could maintain vigilance or nesting in difficult-to-access locations.

The discovery of dinosaur nests on cliff faces and in dense vegetation suggests the selection of protected sleeping areas to avoid predators. Some smaller dinosaurs may have slept in burrows or tree hollows, as evidenced by fossilized burrows containing dinosaur remains in positions suggesting they were using these spaces as shelters. Larger predatory dinosaurs, facing fewer threats, could sleep more openly but might have developed lighter sleep patterns, allowing them to remain alert to opportunities or dangers. These varied sleeping strategies reflect the complex predator-prey relationships that shaped dinosaur behavior and evolution throughout the Mesozoic Era.

Modern Technologies Revealing Ancient Sleep

Cutting-edge technologies are revolutionizing how paleontologists study dinosaur sleep patterns. CT scanning of fossilized dinosaur skulls allows scientists to create detailed models of brain cavities, providing insights into the neurological structures that would have governed sleep. These scans have revealed that many dinosaurs, particularly theropods, had brain structures similar to those in modern birds, supporting hypotheses about bird-like sleep patterns.

Biomechanical modeling using computer simulations helps researchers test hypotheses about physically possible sleeping postures for different dinosaur body types, accounting for their unique anatomical constraints. Geochemical analyses of fossilized nests and surrounding sediments can reveal seasonal patterns and environmental conditions, helping scientists understand when and where dinosaurs might have slept.

Additionally, comparative studies of sleep in modern reptiles and birds using EEG monitoring provide reference points for understanding the evolutionary development of sleep patterns in the dinosaur lineage.

Implications for Dinosaur Behavior and Evolution

Image by Jordyn St. John, via Unsplash

Our emerging understanding of dinosaur sleep patterns has profound implications for interpreting their broader behaviors and evolutionary history. The discovery of bird-like sleeping postures in some dinosaur species provides additional evidence for the evolutionary link between dinosaurs and birds, supporting the now well-established theory that birds evolved from theropod dinosaurs. Sleep behaviors also offer insights into dinosaur social structures, suggesting some species formed complex social groups with cooperative behaviors extending to sleep and protection.

The apparent care many dinosaurs showed for their nests, including sleeping nearby or directly on them, indicates sophisticated parental care strategies evolved early in dinosaur evolution. Moreover, the variety of sleeping adaptations across different dinosaur clades demonstrates how sleep strategies diversified alongside physical adaptations, allowing dinosaurs to occupy numerous ecological niches across the planet for over 160 million years.

Conclusion

Image by Michael Herren, via Unsplash

The study of dinosaur sleep patterns represents a fascinating frontier in paleontology, where fossil evidence, comparative anatomy, and new technologies combine to illuminate previously unseen aspects of prehistoric life. Fossilized nests and rare sleeping posture specimens provide direct glimpses into these intimate moments of dinosaur behavior, while comparisons with modern birds offer valuable context for interpretation.

As research continues, our understanding of how dinosaurs slept will undoubtedly evolve, potentially challenging current assumptions and revealing new insights about these magnificent creatures. What remains clear is that dinosaur sleep, far from being a simple biological necessity, represented a complex behavior shaped by physical constraints, environmental pressures, and evolutionary history—adding another dimension to our appreciation of these remarkable animals that once ruled our planet.