Imagine a creature that looked like it raided a construction site for breakfast, swallowing rocks like they were candy. Picture a dinosaur that traded its fearsome fangs for a duck’s bill, yet somehow thrived in one of Earth’s most competitive ecosystems. This isn’t science fiction – it’s the remarkable reality of some of the most fascinating dinosaurs that ever lived.

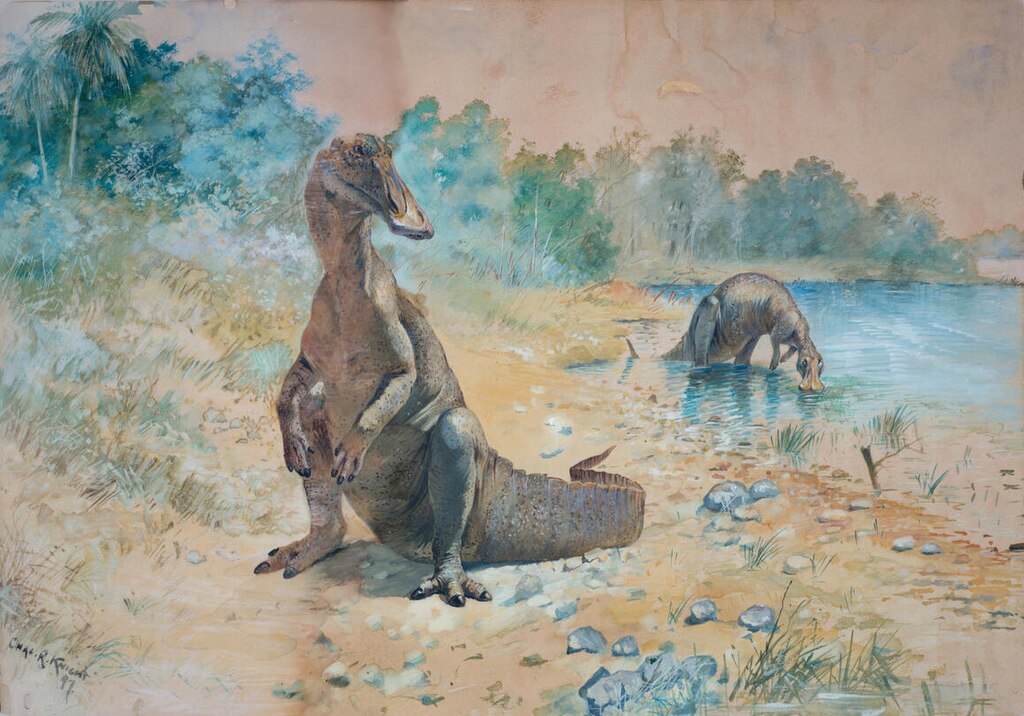

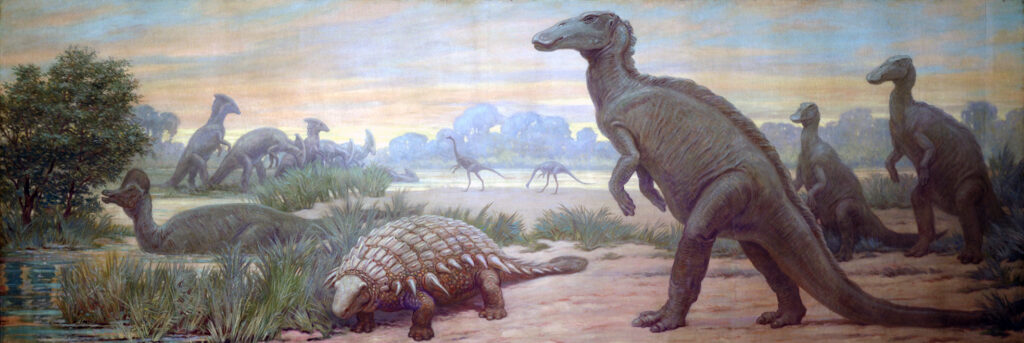

The Duck-Billed Giants That Ruled the Cretaceous

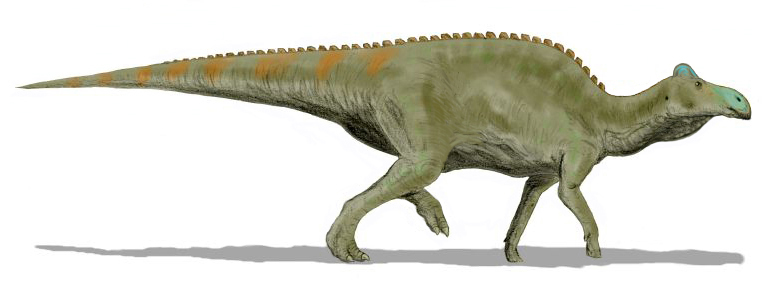

When most people think of dinosaurs, they picture razor-sharp teeth and bone-crushing jaws. But the hadrosaurs, commonly known as duck-billed dinosaurs, threw that rulebook out the window. These massive herbivores dominated the late Cretaceous period with their distinctive flat, elongated snouts that resembled modern waterfowl.

The largest of these gentle giants, like Edmontosaurus, could stretch up to 42 feet long and weigh as much as an elephant. Their duck-like bills weren’t just for show – they were perfectly engineered feeding machines. The broad, flattened structure allowed them to strip vegetation with incredible efficiency, like nature’s own lawn mower.

What made them truly special wasn’t just their size, but their revolutionary approach to eating. While their carnivorous cousins relied on slicing and dicing, these herbivores had discovered something far more sophisticated.

The Mystery of the Missing Teeth

Here’s where things get really interesting. These dinosaurs didn’t actually lack teeth entirely – they had something far more impressive. Hidden behind those duck-like beaks were hundreds of tiny teeth arranged in complex dental batteries. Think of it as having a built-in food processor that could regenerate itself.

Each hadrosaur had between 300 to 1,000 teeth at any given time, constantly growing and replacing themselves as they wore down. Unlike mammals that replace their teeth only once, these dinosaurs were essentially living tooth factories. The worn teeth would fall out, and new ones would immediately take their place.

This dental conveyor belt system allowed them to process the toughest plant materials without ever running out of grinding power. It was like having a self-sharpening industrial grinder in your mouth.

Gastroliths: The Stones That Powered Digestion

But here’s where the story gets truly bizarre. Many of these duck-billed dinosaurs deliberately swallowed stones – not accidentally, but as part of their daily routine. These rocks, called gastroliths, weren’t just random pebbles. They were carefully selected smooth stones that served as an internal grinding system.

Picture your stomach as a rock tumbler, constantly churning and grinding. That’s exactly what happened inside these dinosaurs. The stones would roll around in their muscular stomachs, pulverizing tough plant fibers that even their impressive teeth couldn’t fully break down. It was like having a built-in food processor that never needed batteries.

Modern birds still use this same system today, but imagine scaling it up to an animal the size of a school bus. Some hadrosaur gastroliths were as large as tennis balls, and paleontologists have found fossil evidence of these stone collections still intact inside dinosaur remains.

The Engineering Marvel of Hadrosaurid Skulls

The skull of a duck-billed dinosaur was a masterpiece of biological engineering. The elongated premaxilla and maxilla bones formed that characteristic duck-like bill, but the real magic happened behind the scenes. The skull was designed with multiple chambers and passages that may have enhanced their sense of smell or even helped with sound production.

Some species, like Parasaurolophus, took this even further with elaborate hollow crests that functioned like built-in trumpets. These weren’t just decorative features – they were sophisticated communication devices that could produce different tones and pitches. Scientists have actually recreated the sounds these dinosaurs made by studying the internal structure of their crests.

The eye sockets were positioned to give them excellent peripheral vision, crucial for spotting predators while their heads were down feeding. Every aspect of their skull design served a specific purpose in their plant-eating lifestyle.

How Duck Bills Became Nature’s Perfect Harvesting Tools

The duck-like bill wasn’t just a quirky evolutionary accident – it was a precision tool honed by millions of years of natural selection. The broad, flat surface was perfect for cropping low-growing vegetation, while the slightly hooked tip could strip leaves from branches with surgical precision.

Unlike the narrow snouts of carnivores designed for grabbing prey, these bills were optimized for maximum surface area contact with plant material. They could effectively “mow” through fields of ferns, conifers, and flowering plants that were beginning to diversify during the Cretaceous period.

The edges of their bills were also lined with a horny covering, similar to what we see in modern ducks and geese. This gave them additional cutting power and helped prevent wear on the underlying bone structure.

The Sophisticated Chewing Mechanism

What truly set these dinosaurs apart was their revolutionary chewing mechanism. While most reptiles simply swallow their food whole, hadrosaurs developed a complex system of jaw movement that allowed for true mastication. They could move their jaws not just up and down, but also side to side, creating a grinding motion that thoroughly processed plant material.

This wasn’t just simple chewing – it was a sophisticated pulverizing system. The multiple rows of teeth worked together like a biological mill, breaking down cellulose and other tough plant compounds that would otherwise be indigestible. The jaw muscles were incredibly powerful, capable of generating enormous pressure to crush even the toughest vegetation.

Their skulls show clear evidence of the muscle attachment points needed for this complex chewing action. The temporal and masseter muscles were massive, giving these dinosaurs the jaw power of a industrial crusher.

Digestive Powerhouses of the Mesozoic

The digestive system of duck-billed dinosaurs was nothing short of extraordinary. Their stomachs were multi-chambered affairs, similar to modern ruminants like cows, but taken to an extreme level. The first chamber was where those carefully selected gastroliths did their work, grinding and churning plant material into a digestible paste.

The sheer volume of their digestive tract was staggering. Some estimates suggest that a large hadrosaur’s gut could hold over 1,000 pounds of plant material at any given time. That’s like having a small car’s worth of salad in your stomach, constantly being processed and churned.

But unlike modern ruminants that regurgitate and re-chew their food, these dinosaurs got it right the first time. Their combination of extensive chewing and gastrolith grinding meant that plant material was thoroughly processed before moving through the rest of their digestive system.

The Social Dynamics of Herd Feeding

These duck-billed giants weren’t solitary creatures – they lived and fed in massive herds that could number in the thousands. Imagine the sight of hundreds of these 30-foot-long dinosaurs moving across the landscape like a prehistoric cattle drive, their duck bills constantly working as they stripped vegetation bare.

Fossil evidence shows clear signs of herd behavior, with trackways revealing groups of different-aged individuals moving together. The younger dinosaurs stayed in the center of the herd, protected by the adults on the outside. This social feeding strategy allowed them to efficiently process vast areas of vegetation while maintaining safety in numbers.

Their herding behavior also meant they had to be incredibly efficient feeders. With so many mouths to feed in one area, they couldn’t afford to be picky eaters. Their versatile bills and powerful digestive systems allowed them to consume almost any plant material available.

Survival Strategies in a Predator-Rich World

Living in the same time and place as Tyrannosaurus rex and other massive predators required some serious survival strategies. The duck-billed dinosaurs’ feeding adaptations weren’t just about efficiency – they were about staying alive long enough to reproduce.

Their ability to quickly process low-quality plant material meant they could feed in areas where other herbivores couldn’t survive. While other dinosaurs might need to spend all day searching for the choicest vegetation, hadrosaurs could make do with whatever was available and spend more time watching for danger.

The gastrolith system also provided an unexpected advantage – it allowed them to extract maximum nutrition from minimal food. In times of scarcity or when hiding from predators, they could survive on tough, fibrous plants that other animals couldn’t digest.

The Evolutionary Arms Race

The development of these sophisticated feeding mechanisms wasn’t happening in isolation. As plants evolved better defenses – tougher leaves, toxic compounds, thorns and spines – the duck-billed dinosaurs evolved better ways to process them. It was an evolutionary arms race that lasted millions of years.

The rise of flowering plants during the Cretaceous period provided new opportunities and challenges. These new plants often had different nutritional profiles and defense mechanisms than the conifers and ferns that had dominated earlier periods. The hadrosaurs’ adaptable feeding system allowed them to take advantage of this botanical revolution.

Their success is evident in the fossil record – duck-billed dinosaurs became some of the most abundant and diverse herbivores of the late Cretaceous. They had found a winning formula that allowed them to thrive in changing environments.

Modern Echoes of Ancient Feeding Strategies

Remarkably, we can see echoes of these ancient feeding strategies in modern animals. Many birds still use gastroliths to aid digestion, though none approach the scale of what the hadrosaurs achieved. Ducks and geese, with their similar bill shapes, show us how effective this feeding strategy can be.

Even some modern herbivorous mammals have convergently evolved similar solutions. Horses, for example, have developed complex dental batteries and powerful jaw muscles for processing grass – though they achieve this through different evolutionary pathways than the dinosaurs did.

The principle remains the same: to successfully exploit low-quality plant food, you need specialized equipment for harvesting, processing, and digesting it. The hadrosaurs had perfected this system long before mammals even began to diversify.

The Great Extinction and Its Aftermath

The duck-billed dinosaurs’ reign came to an abrupt end 66 million years ago with the mass extinction event that ended the Mesozoic Era. Despite their sophisticated feeding adaptations and apparent success, they couldn’t survive the catastrophic environmental changes that followed the asteroid impact.

Ironically, their specialized feeding system may have contributed to their downfall. When plant communities collapsed following the extinction event, these highly efficient but specialized feeders may have been less adaptable than more generalized animals. The very traits that made them successful in stable environments became liabilities in a rapidly changing world.

Their ecological niche was eventually filled by mammals, but it took millions of years for any herbivore to achieve the same level of feeding sophistication. The hadrosaurs had set a standard that wouldn’t be matched again until the evolution of modern grazing animals.

What We’re Still Learning

New discoveries continue to reveal surprising details about these remarkable dinosaurs. Advanced imaging techniques have allowed scientists to study the internal structure of fossilized gastroliths, revealing wear patterns that tell us exactly how they functioned. CT scans of skulls have revealed previously unknown details about their chewing mechanisms and sensory capabilities.

Recent finds have also shown that some duck-billed dinosaurs had more complex social behaviors than previously thought. Evidence of parental care, communication systems, and even possible seasonal migrations paint a picture of intelligent, socially complex animals that were far more than simple eating machines.

Perhaps most intriguingly, some researchers are investigating whether these dinosaurs might have had some form of fermentation-based digestion, similar to what we see in modern ruminants. If true, it would represent yet another level of sophistication in their feeding strategy.

The Legacy of the Duck-Billed Dinosaurs

The duck-billed dinosaurs represent one of evolution’s most successful experiments in herbivory. They proved that you don’t need massive teeth or powerful claws to dominate an ecosystem – sometimes the most effective strategy is to simply be really, really good at eating plants.

Their legacy lives on in the modern world through the animals that have adopted similar strategies. From the gastrolith-using birds to the complex dental systems of grazing mammals, the solutions pioneered by hadrosaurs continue to influence how animals extract nutrition from plant material.

These dinosaurs showed that innovation in feeding strategy could be just as important as size or strength in determining evolutionary success. They found a way to turn one of the most abundant but difficult-to-digest food sources on Earth into the foundation for a thriving ecosystem. When you think about it, that’s pretty impressive for an animal that looked like it had raided a duck pond for its head and a quarry for its breakfast.