In the realm of paleontology, few discoveries have challenged our understanding of prehistoric life quite like the evidence of aquatic dinosaurs. While we’ve long known about marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, true dinosaurs were traditionally considered terrestrial creatures. However, groundbreaking discoveries have revealed compelling evidence that some dinosaur species may have been adapted for a predominantly aquatic lifestyle. These findings have sent ripples through the scientific community, forcing experts to reconsider long-held assumptions about dinosaur evolution and behavior. The most remarkable of these aquatic dinosaurs, Spinosaurus aegyptiacus, has transformed our understanding of dinosaur diversity and adaptation.

The Spinosaurus Mystery Unraveled

Spinosaurus aegyptiacus first entered scientific record in 1915 when German paleontologist Ernst Stromer described fossils found in Egypt. Unfortunately, these original specimens were destroyed during World War II when Allied bombing raids struck the Munich museum housing them. For decades afterward, Spinosaurus remained poorly understood, known primarily for its impressive sail-like structure extending from its back. The mystery deepened as new, fragmentary discoveries emerged, suggesting this creature might be different from other theropod dinosaurs. It wasn’t until 2014, when paleontologist Nizar Ibrahim led a team that discovered more complete remains in Morocco, that the aquatic adaptations of Spinosaurus became clear. This discovery represented one of the most significant revisions to dinosaur science in decades, establishing Spinosaurus as the first known semi-aquatic dinosaur.

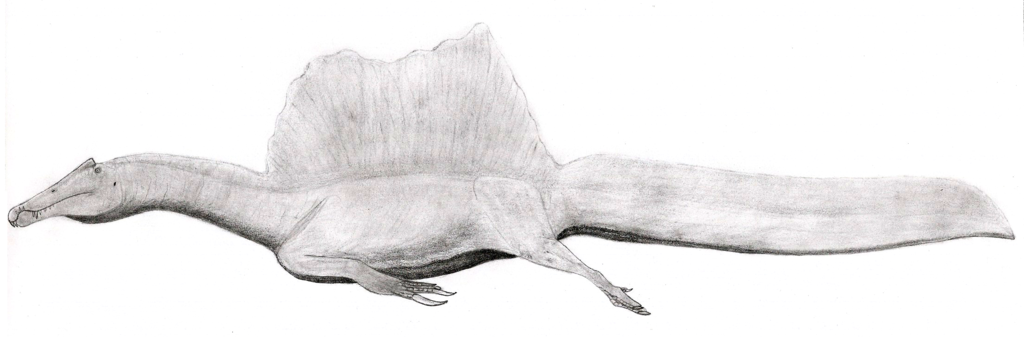

An Unmistakable Profile: Spinosaurus Anatomy

Spinosaurus possessed one of the most distinctive silhouettes in the dinosaur kingdom, growing to an estimated length of 50-59 feet, possibly making it larger than even Tyrannosaurus rex. Its most notable feature was the sail-like structure formed by elongated neural spines projecting from its vertebrae, reaching heights of up to 7 feet. Unlike the compact tails of most theropods, Spinosaurus possessed a deep, flexible tail resembling a paddle or fin, perfectly adapted for powerful swimming movements. Its skull was elongated and crocodile-like, with conical teeth ideal for catching slippery prey. The nostrils were positioned high on the skull, allowing it to breathe while partially submerged. These unique anatomical features collectively paint the picture of a creature supremely adapted to a life spent hunting in water environments, challenging the long-held notion that all dinosaurs were strictly terrestrial.

Density Adaptations: Built for Buoyancy

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence for Spinosaurus’s aquatic lifestyle comes from studies of its bone density. Research published in 2020 revealed that Spinosaurus had remarkably dense bones compared to other theropod dinosaurs. This adaptation, known as pachyostosis, is commonly seen in aquatic mammals like manatees and early whales, helping them maintain buoyancy underwater. Scientists analyzed the bone density of Spinosaurus limbs and compared them with both terrestrial dinosaurs and known aquatic and semi-aquatic animals. The results showed that Spinosaurus bones were significantly denser, with less internal cavity space than terrestrial dinosaurs. This adaptation would have helped the massive creature control its buoyancy in water, allowing it to dive and swim effectively despite its enormous size. Such specialized bone structure provides strong evidence that Spinosaurus spent considerable time in aquatic environments.

The Revolutionary Tail Discovery

Perhaps the most definitive evidence of Spinosaurus’s aquatic lifestyle came with the 2020 discovery and analysis of a remarkably complete tail fossil. This tail revealed a structure utterly unique among dinosaurs – a flexible, fin-like appendage more reminiscent of a crocodile or newt than any known dinosaur. The tall neural spines created a paddle-like shape that would have been perfect for propulsion through water. Computer modeling and fluid dynamics testing confirmed that this tail would have been an efficient swimming apparatus, capable of generating significant thrust with lateral movements. Laboratory experiments with physical models demonstrated that the tail design was specifically optimized for aquatic locomotion rather than terrestrial movement. This tail structure represents one of the most dramatic adaptations ever documented in dinosaur evolution, effectively transforming our understanding of how diverse dinosaur locomotion could be.

The Aquatic Predator’s Diet

Spinosaurus’s feeding ecology reflects its specialization as an aquatic predator. Isotope analysis of Spinosaurus teeth reveals chemical signatures consistent with a diet rich in aquatic prey, particularly fish. Its long, conical teeth were ideal for snaring slippery prey underwater, functioning more like those of crocodilians than the serrated, blade-like teeth of terrestrial predators like Tyrannosaurus. Fossil evidence suggests that Spinosaurus hunted both massive prehistoric fish like the car-sized Onchopristis (a sawfish relative) and lungfish that inhabited its North African river systems. Some fossils even show direct evidence of predation, with Spinosaurus teeth found embedded in the remains of large fish. Unlike most theropod dinosaurs, which were adapted for pursuing terrestrial prey, Spinosaurus appears to have been specialized for a piscivorous lifestyle, with its long snout and specialized teeth perfect for hunting in the water column.

The Habitat: Ancient North African Waterways

During the mid-Cretaceous period approximately 95-100 million years ago, Northern Africa presented a dramatically different landscape than today’s Sahara Desert. Spinosaurus inhabited a vast system of rivers, deltas, and coastal marshlands often referred to as the “River of Giants” due to the enormous aquatic creatures that thrived there. This environment resembled today’s Amazon Basin or Everglades, with extensive waterways cutting through lush forests. The region supported a rich ecosystem including massive crocodilians, car-sized fish, turtles, and other aquatic species. Geological evidence indicates frequent seasonal flooding, creating expansive wetlands that would have provided perfect hunting grounds for a semi-aquatic predator. Fossil evidence of Spinosaurus has been recovered primarily from the Kem Kem beds of Morocco and equivalent formations in Egypt, areas that preserve ancient river systems where this unique dinosaur once reigned as the apex predator.

Controversial Locomotion: How Did It Move?

The question of how Spinosaurus moved both on land and in water remains one of the most hotly debated aspects of this dinosaur’s biology. While the paddle-like tail provides compelling evidence for swimming capabilities, paleontologists disagree about how competent Spinosaurus would have been on land. Some researchers argue it was primarily quadrupedal, using all four limbs to move on land due to its front-heavy build and unusual proportions. Others maintain it remained bipedal but awkward on land, perhaps moving more like a modern penguin. The most extreme position suggests Spinosaurus was so specialized for aquatic life that it was nearly helpless on land, similar to modern seals. Biomechanical studies of its limb proportions, center of gravity, and muscle attachment points continue to fuel this scientific debate. Regardless of the specifics, most experts now agree that Spinosaurus was better adapted for movement in water than on land, representing a dramatic evolutionary experiment in dinosaur locomotion.

The Evolutionary Significance

The discovery of Spinosaurus’s aquatic adaptations represents a watershed moment in our understanding of dinosaur evolution. Previously, paleontologists had drawn a clear line between true dinosaurs, which were thought to be exclusively terrestrial, and marine reptiles like plesiosaurs and ichthyosaurs, which weren’t dinosaurs at all. Spinosaurus blurs this distinction, demonstrating that at least some dinosaur lineages experimented with aquatic lifestyles. This revelation suggests that dinosaur adaptation was more diverse and flexible than previously recognized. From an evolutionary perspective, Spinosaurus represents a unique case of convergent evolution, developing features similar to those seen in unrelated aquatic animals through adaptation to similar environmental pressures. This example of a dinosaur lineage independently evolving aquatic adaptations provides valuable insights into the evolutionary processes that drive specialization and niche exploitation in vertebrate evolution.

Comparisons to Other Water-Adapted Reptiles

Spinosaurus represents just one evolutionary approach to an aquatic lifestyle among reptiles. Unlike fully aquatic prehistoric reptiles such as plesiosaurs, ichthyosaurs, and mosasaurs, which evolved paddle-like limbs and lost their connection to land, Spinosaurus retained limbs that could still function on land, albeit less efficiently. Modern analogues to Spinosaurus’s semi-aquatic lifestyle might include crocodilians, which dominate in water but can move on land, or marine iguanas, which feed in water but return to land. Other dinosaurs like the duck-billed hadrosaurs show some adaptations for swimming and wading but nothing approaching Spinosaurus’s level of aquatic specialization. Notably, while many prehistoric reptiles evolved flippers for swimming, Spinosaurus took a different evolutionary approach by modifying its tail for aquatic propulsion while maintaining limbs for potential terrestrial movement. This unique evolutionary solution highlights the diversity of adaptations that can emerge when different animal groups independently adapt to similar ecological niches.

Scientific Controversy and Competing Theories

The aquatic interpretation of Spinosaurus has not been embraced without controversy in the scientific community. Some paleontologists remain skeptical about the degree of aquatic adaptation, suggesting Spinosaurus may have been more of a shoreline wader that hunted from riverbanks, similar to modern herons or storks. Critics point to certain anatomical features, such as the placement of the nostrils at the end of the snout rather than on top of the head, which might complicate a highly aquatic lifestyle. Others question whether the limb proportions would have allowed effective swimming or diving. Some researchers propose alternative functions for the sail, suggesting it served primarily for display or thermoregulation rather than aquatic locomotion. These ongoing debates reflect the challenge of interpreting behavior and ecology from fossil evidence alone. Despite these disagreements, the scientific consensus has increasingly shifted toward accepting Spinosaurus as at least partially aquatic, though the exact degree of aquatic specialization remains under investigation.

Recreating Spinosaurus: Challenges in Paleoart

The evolving understanding of Spinosaurus has created unique challenges for artists attempting to accurately depict this unusual dinosaur. For decades, Spinosaurus was portrayed as a fairly conventional theropod with a sail, similar to a larger version of Allosaurus or other well-known predatory dinosaurs. Following the 2014 discovery suggesting more aquatic adaptations, paleoartists began reimagining Spinosaurus with crocodile-like features, showing it hunting in shallow water. The 2020 tail discovery prompted another round of dramatic revisions, with artists now depicting Spinosaurus swimming with its paddle-like tail propelling it through deep water. This rapid evolution in scientific understanding has required artists to repeatedly update their interpretations, highlighting the dynamic nature of paleontological knowledge. Modern paleoartists must balance scientific accuracy with the inherent uncertainties that come with recreating an animal known only from incomplete fossil remains. The most current reconstructions typically show Spinosaurus as a crocodile-like swimmer with a deep tail, high-set eyes, and a lifestyle predominantly spent in water – a far cry from how this dinosaur was envisioned just a decade ago.

The Search for Other Aquatic Dinosaurs

The confirmation of Spinosaurus as an aquatic dinosaur has sparked renewed interest in searching for other dinosaur species that might have adapted to life in water. Paleontologists are reexamining fossils of related spinosaurids like Baryonyx and Suchomimus, which show some adaptations for fishing but appear less specialized for aquatic life than Spinosaurus. Some duck-billed hadrosaurs show adaptations that might have facilitated swimming, including compressed tails that could have aided in aquatic propulsion. Certain theropods found in coastal or riverine deposits are now being scrutinized for potential aquatic adaptations that might have been overlooked. The search extends beyond obvious anatomical features to include chemical analysis of bones and teeth that might reveal dietary patterns consistent with aquatic feeding. While no other dinosaur has yet been found with Spinosaurus’s degree of aquatic specialization, the discovery has fundamentally changed how paleontologists approach the question of dinosaur habitat and behavior, opening the possibility that other dinosaur lineages may have experimented with aquatic lifestyles to varying degrees.

Future Research and Unanswered Questions

Despite significant advances in our understanding of Spinosaurus, numerous questions remain unanswered about this remarkable dinosaur. Paleontologists continue searching for more complete skeletons that could resolve debates about its posture, locomotion, and degree of aquatic adaptation. Advanced technologies are being deployed to analyze existing fossils, including CT scanning to examine internal bone structure and digital modeling to test locomotion hypotheses. One major unanswered question concerns reproduction – did Spinosaurus lay eggs on land like other dinosaurs, and if so, how did this highly aquatic creature manage this terrestrial activity? Scientists also seek to better understand the evolutionary pathway that led to Spinosaurus’s unique adaptations and whether these represented a brief evolutionary experiment or a successful strategy maintained over millions of years. The ongoing exploration of fossil beds in North Africa offers the potential for new discoveries that could further illuminate the biology of this most unusual dinosaur. As research continues, our understanding of Spinosaurus will undoubtedly continue to evolve, perhaps with further surprises that challenge our conceptions of dinosaur diversity.

The discovery of Spinosaurus as an aquatic dinosaur stands as one of paleontology’s most significant revelations of the 21st century. It has fundamentally altered our understanding of dinosaur adaptation and diversity, demonstrating that these remarkable animals conquered not just terrestrial environments but aquatic ones as well. As research continues, Spinosaurus serves as a powerful reminder that despite centuries of fossil collecting and decades of intense scientific study, the world of dinosaurs still holds profound surprises. This unexpected aquatic dinosaur challenges us to reconsider our assumptions about prehistoric life and remains an emblem of how new discoveries can dramatically reshape our understanding of Earth’s ancient past.