Imagine diving into an ancient ocean where massive predators with eyes the size of dinner plates patrol the depths. Picture creatures that look like dolphins but stretch as long as school buses, their razor-sharp teeth glistening as they hunt. This wasn’t fantasy—this was the reality of Earth’s oceans during the Mesozoic Era, when ichthyosaurs ruled the seas like underwater dragons.

The Dawn of Marine Reptile Dominance

The story of ichthyosaurs begins around 250 million years ago, during the Early Triassic period when life on Earth was recovering from the devastating Permian-Triassic extinction event. These remarkable reptiles didn’t start in the water—they were land-dwelling creatures that made an extraordinary evolutionary leap back into the oceans. Think of it like wolves deciding to become whales, except this actually happened.

What makes this transition so fascinating is how quickly these reptiles adapted to marine life. Within just a few million years, they had developed streamlined bodies, powerful tails, and sophisticated hunting abilities. The earliest ichthyosaurs were relatively small, but they laid the foundation for what would become some of the ocean’s most successful predators.

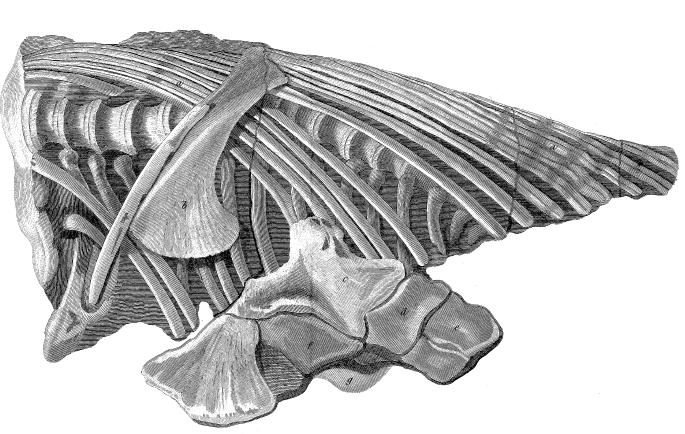

Anatomy of an Ancient Sea Dragon

Ichthyosaurs possessed bodies that seemed almost alien yet perfectly designed for underwater life. Their most striking feature was their enormous eyes—some species had eyes over 10 inches in diameter, making them among the largest eyes of any vertebrate that ever lived. These massive visual organs allowed them to hunt in the murky depths where sunlight barely penetrated.

Their bodies were torpedo-shaped, similar to modern dolphins and sharks, demonstrating a perfect example of convergent evolution. Four powerful flippers propelled them through the water with incredible efficiency. Their tails, unlike those of fish, moved vertically rather than horizontally, powered by a distinctive downward bend in their spine that created a crescent-shaped tail fin.

Perhaps most remarkably, ichthyosaurs had developed a streamlined snout filled with sharp, conical teeth perfectly suited for catching slippery prey. Some species had over 200 teeth, creating a formidable trap for any unfortunate fish or squid that came too close.

The Jurassic Ocean Ecosystem

During the Jurassic period, roughly 200 to 145 million years ago, Earth’s oceans were vastly different from today. Sea levels were much higher, creating vast shallow seas that covered much of what is now Europe and North America. These warm, tropical waters teemed with life—ammonites spiraled through the water column, marine crocodiles lurked in coastal areas, and plesiosaurs patrolled the middle depths.

Into this aquatic paradise, ichthyosaurs inserted themselves as apex predators. They occupied multiple ecological niches, from small fish-eaters to massive deep-sea hunters. The diversity was staggering—some species were no bigger than a person, while others rivaled modern sperm whales in size.

The abundance of prey made the Jurassic seas a perfect hunting ground. Belemnites, ancient relatives of squid, were particularly abundant and formed a crucial part of many ichthyosaur diets. Fish were plentiful, and even other marine reptiles occasionally became prey for the largest ichthyosaur species.

Giants of the Deep: Temnodontosaurus

Among the most impressive ichthyosaurs was Temnodontosaurus, a massive predator that could reach lengths of up to 40 feet—roughly the size of a modern humpback whale. These giants prowled the Early Jurassic seas with an almost mythical presence, their enormous bulk moving through the water with surprising grace.

What made Temnodontosaurus truly fearsome was its combination of size and speed. Despite their massive bulk, these creatures were built for pursuit hunting, capable of sudden bursts of speed that would make them formidable predators. Their teeth, some over 4 inches long, could deliver devastating bites to prey or rivals.

Fossil evidence suggests these giants were successful hunters, with stomach contents revealing they fed on a variety of prey including fish, squid, and even smaller marine reptiles. Their success in the Early Jurassic seas demonstrates just how effectively ichthyosaurs had adapted to their marine environment.

The Speed Demons: Ophthalmosaurus

If Temnodontosaurus was the heavyweight champion of Jurassic seas, then Ophthalmosaurus was the speed demon. This medium-sized ichthyosaur, measuring around 15 feet in length, was built for one thing: speed. Its body was even more streamlined than its larger cousins, with reduced limbs and a perfectly hydrodynamic shape.

The name Ophthalmosaurus literally means “eye lizard,” and for good reason. These creatures possessed proportionally enormous eyes that dominated their skull, suggesting they were specialized for hunting in low-light conditions. They might have been the world’s first deep-sea specialists, diving to depths where their incredible vision gave them a crucial advantage.

Recent studies suggest Ophthalmosaurus could dive to depths of over 1,600 feet, rivaling modern deep-diving whales. Their ribcage was specially adapted to compress under pressure, allowing them to explore parts of the ocean that remained off-limits to other marine reptiles of their time.

Fossilized Motherhood: Reproductive Revelations

One of the most remarkable discoveries in ichthyosaur paleontology came from perfectly preserved fossils showing female ichthyosaurs giving birth. These incredible specimens revealed that ichthyosaurs didn’t lay eggs like most reptiles—instead, they gave birth to live young, tail-first, just like modern whales and dolphins.

The fossil record shows baby ichthyosaurs were born remarkably well-developed, ready to swim and hunt almost immediately. This live-birth strategy was a major evolutionary advantage in the open ocean, where eggs would be vulnerable to predators and environmental changes.

Some fossils even show what appears to be family groups, suggesting these ancient sea dragons may have had complex social behaviors. The care and protection of young would have been crucial for species survival in the competitive Jurassic seas.

The Hunting Strategies of Ancient Predators

Ichthyosaurs employed a variety of hunting strategies that would make modern marine predators envious. Their excellent vision and streamlined bodies made them perfect pursuit predators, capable of chasing down fast-moving prey over long distances. Some species likely hunted in coordinated groups, similar to modern dolphins or orcas.

The diversity in tooth shapes and jaw structures suggests different species specialized in different prey types. Some had long, narrow snouts perfect for catching fish, while others had shorter, more powerful jaws designed for crushing hard-shelled prey like ammonites.

Perhaps most impressively, the largest ichthyosaurs may have been capable of suction feeding, using their powerful jaws to create a vacuum that would draw prey directly into their mouths. This technique, also used by modern sperm whales, would have made them incredibly efficient predators in the deep ocean.

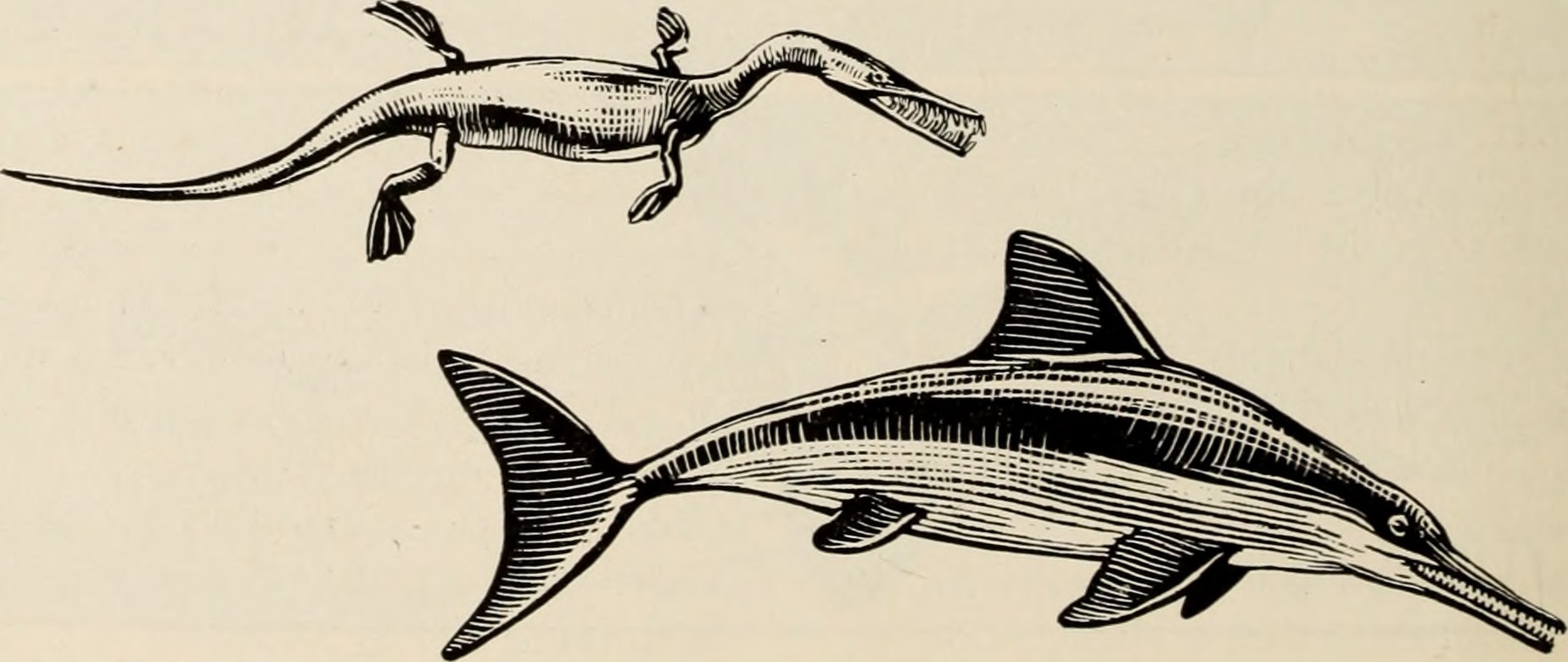

Evolutionary Convergence: Nature’s Repeated Success Story

The similarities between ichthyosaurs and modern marine mammals are so striking that they represent one of the best examples of convergent evolution in the fossil record. Both groups independently evolved streamlined bodies, powerful tails, and sophisticated echolocation abilities—proving that certain body plans are simply optimal for marine life.

This convergence extends beyond just physical appearance. Both ichthyosaurs and modern whales evolved live birth, complex social behaviors, and deep-diving capabilities. It’s as if nature had a blueprint for successful marine predators and followed it twice, separated by millions of years.

The fact that two completely different groups of animals—reptiles and mammals—independently evolved such similar solutions to marine life challenges our understanding of evolutionary inevitability. It suggests that certain environmental pressures consistently produce similar biological solutions.

The Mysterious Decline

Despite their incredible success, ichthyosaurs began to decline during the Late Jurassic period, long before the famous asteroid impact that ended the dinosaurs. This mysterious decline has puzzled scientists for decades, especially given how well-adapted these creatures were to marine life.

Several factors may have contributed to their downfall. Competition from other marine reptiles, particularly plesiosaurs and marine crocodiles, may have reduced their available ecological niches. Changes in ocean chemistry and temperature could have affected their prey base, making survival increasingly difficult.

Perhaps most significantly, the rise of new predators, including early sharks and bony fish, may have outcompeted ichthyosaurs for resources. The oceans were becoming increasingly crowded with efficient predators, and ichthyosaurs may have simply been squeezed out of their traditional roles.

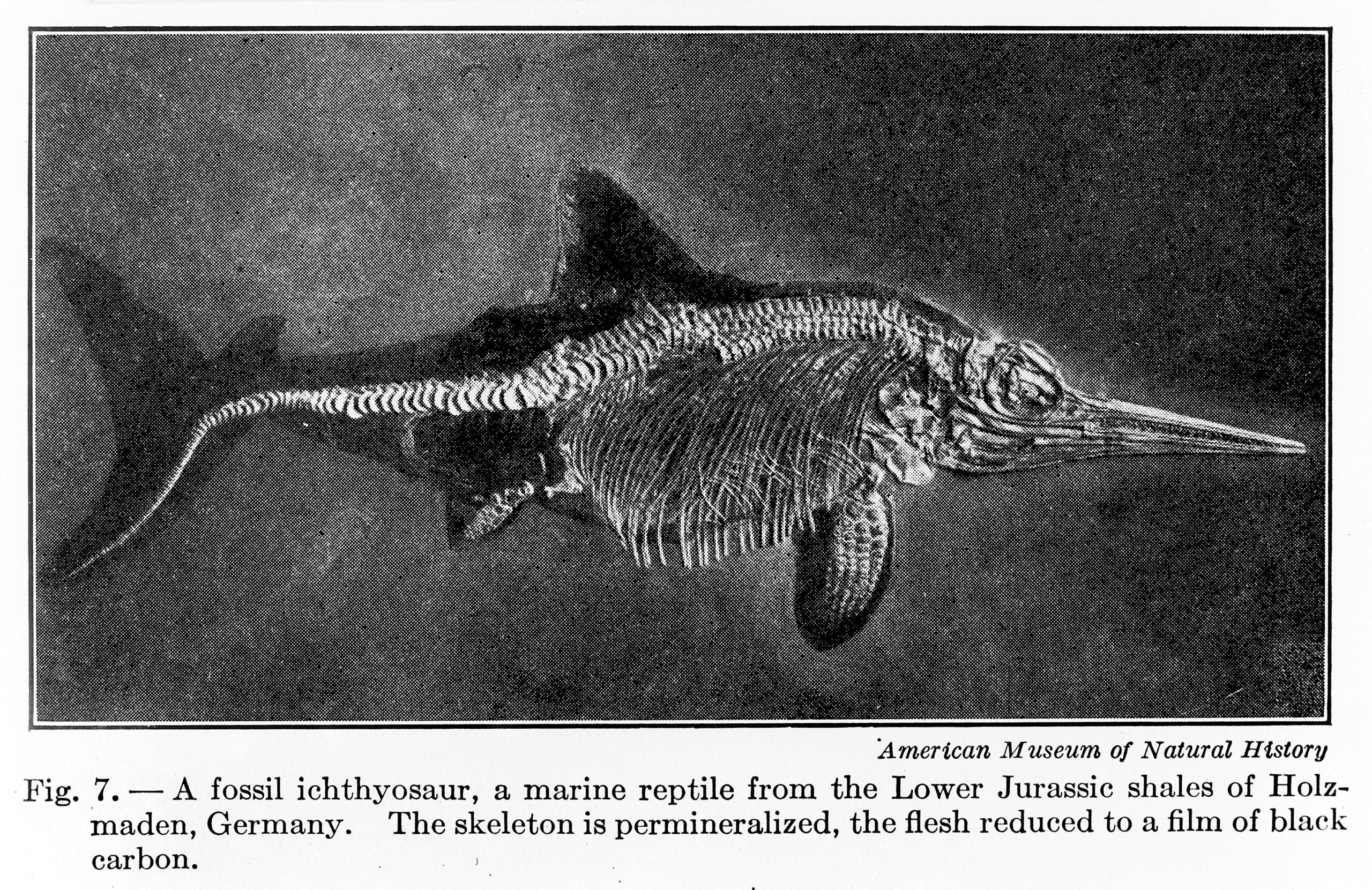

Fossil Discoveries That Changed Everything

The study of ichthyosaurs has been revolutionized by spectacular fossil discoveries, particularly in Germany’s Holzmaden formation and England’s Jurassic Coast. These sites have yielded fossils of unprecedented quality, preserving not just bones but also soft tissues, stomach contents, and even skin impressions.

One of the most famous discoveries was made by Mary Anning, a pioneering fossil collector who found the first scientifically recognized ichthyosaur fossil in 1811. Her discoveries helped establish paleontology as a legitimate scientific discipline and challenged contemporary understanding of Earth’s history.

Modern discoveries continue to surprise scientists. Recent finds have revealed ichthyosaurs with preserved coloration, showing that at least some species had dark backs and light bellies—a pattern called countershading that’s common in modern marine animals.

The Exceptional Preservation of Soft Tissues

What makes ichthyosaur fossils truly extraordinary is the preservation of soft tissues that normally decay quickly after death. Some specimens preserve skin, muscles, and even internal organs, providing unprecedented insights into how these ancient creatures lived and died.

The preservation of ichthyosaur skin has revealed that these reptiles had a smooth, rubbery texture similar to modern dolphins. Some fossils even show the outline of dorsal fins and tail flukes, structures that were completely unknown from skeletal remains alone.

Perhaps most remarkably, scientists have discovered ichthyosaur fossils with preserved liver tissue, allowing them to understand how these creatures processed the massive amounts of food they needed to sustain their active lifestyles. These discoveries have transformed our understanding of ancient marine ecosystems.

Modern Technology Reveals Ancient Secrets

Today’s paleontologists use cutting-edge technology to unlock secrets that early fossil hunters could never have imagined. CT scanning allows scientists to peer inside fossil skulls without damaging them, revealing brain structures and inner ear anatomy that provides clues about ichthyosaur behavior and sensory capabilities.

Chemical analysis of fossil bones has revealed information about ichthyosaur body temperature, diving behavior, and even migration patterns. These techniques have shown that ichthyosaurs were warm-blooded, active predators rather than the cold-blooded reptiles scientists once assumed them to be.

3D modeling and computational fluid dynamics now allow researchers to test theories about ichthyosaur swimming abilities and hunting strategies. These studies have confirmed that ichthyosaurs were among the most efficient swimmers in Earth’s history, capable of both high-speed pursuits and energy-efficient long-distance travel.

The Legacy of Jurassic Sea Dragons

The story of ichthyosaurs is more than just an account of ancient predators—it’s a testament to life’s incredible adaptability and the power of evolution to find solutions to environmental challenges. These remarkable creatures proved that reptiles could be just as successful in marine environments as any mammal or fish.

Their legacy lives on in modern marine ecosystems, where their ecological roles have been filled by whales, dolphins, and other marine mammals. The convergent evolution between ichthyosaurs and modern marine mammals demonstrates that certain body plans and behaviors are simply optimal for ocean life.

Understanding ichthyosaurs also provides crucial insights into how modern marine ecosystems might respond to environmental changes. Their mysterious decline serves as a reminder that even the most successful species can face extinction when environmental conditions change rapidly.

Conclusion: Echoes from the Deep

The ichthyosaurs of the Jurassic seas were more than just ancient reptiles—they were evolutionary pioneers that pushed the boundaries of what was possible for life on Earth. Their success story lasted over 150 million years, far longer than humans have existed, and their influence can still be seen in today’s oceans.

These sea dragons remind us that evolution is not a ladder leading to predetermined outcomes, but rather a web of possibilities where life finds remarkable solutions to environmental challenges. The next time you watch a dolphin gracefully arc through the waves, remember that you’re witnessing the echo of an ancient design perfected by reptiles that ruled the seas when dinosaurs walked the land.

What other secrets might these ancient oceans still hold, waiting to be discovered in the rocks beneath our feet?