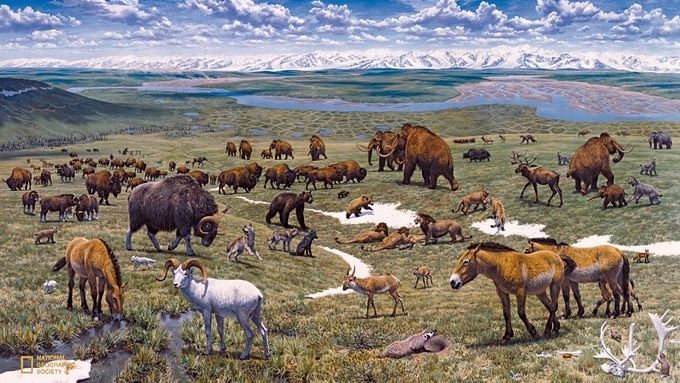

Picture this: Just 15,000 years ago, North America was home to creatures that would make today’s largest animals look like house pets. Massive woolly mammoths thundered across frozen landscapes, saber-toothed cats prowled through ancient forests, and ground sloths the size of small cars lumbered through prehistoric meadows. Then, in what scientists consider the blink of an eye in geological terms, they vanished. The question that haunts researchers today isn’t just how these magnificent beasts disappeared, but whether our own ancestors played the starring role in one of history’s most devastating extinction events.

The Magnificent Giants That Once Ruled Earth

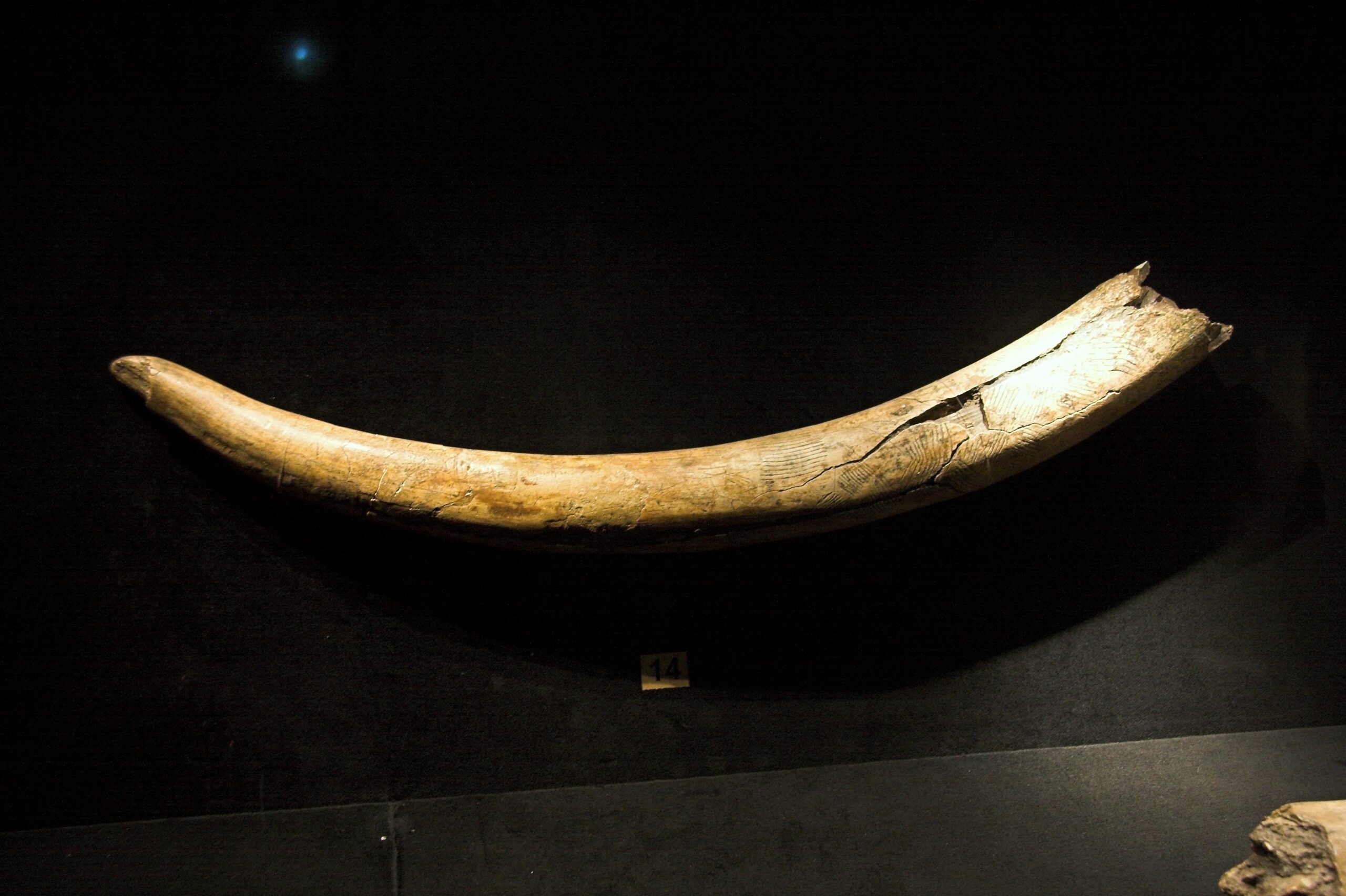

The late Pleistocene epoch showcased nature’s most spectacular creations, with megafauna that defied modern imagination. Woolly mammoths, standing 11 feet tall and weighing up to 8 tons, roamed from Alaska to Siberia in massive herds. These gentle giants possessed curved tusks that could span 16 feet and thick, shaggy coats that protected them from temperatures plummeting to -40°F.

North America hosted an even more diverse cast of colossal characters. Giant ground sloths called Megalonyx reached lengths of 10 feet and possessed claws longer than kitchen knives. The massive cave bear, weighing over 1,500 pounds, dwarfed today’s grizzlies by comparison. Perhaps most terrifying of all was the short-faced bear, standing 12 feet tall on its hind legs and capable of running 40 miles per hour.

Australia’s megafauna included the Diprotodon, a marsupial the size of a hippopotamus, and the fearsome Megalania, a monitor lizard stretching 23 feet long. These creatures had thrived for millions of years, perfectly adapted to their environments and seemingly invincible in their dominance.

The Great Vanishing Act

Between 50,000 and 10,000 years ago, approximately 80% of large mammal species weighing over 100 pounds disappeared from the planet. This extinction event struck with shocking precision, targeting the largest animals while leaving smaller species relatively untouched. The timing wasn’t random – it coincided suspiciously with human migration patterns across the globe.

The scale of this loss was staggering. In North America alone, 33 genera of large mammals vanished, including mammoths, mastodons, giant beavers, and American cheetahs. Europe lost its cave lions, woolly rhinoceros, and giant deer. Australia witnessed the disappearance of over 85% of its megafauna weighing more than 100 pounds.

What makes this extinction particularly mysterious is its selectivity. While giants fell, smaller animals like rabbits, mice, and birds largely survived. This pattern suggests something more targeted than a simple environmental catastrophe, pointing toward a cause that specifically affected large, slow-reproducing species.

Human Arrival: A Deadly Coincidence?

The correlation between human arrival and megafauna extinction is so striking it’s hard to ignore. Archaeological evidence shows that wherever humans first set foot on new continents, mass extinctions followed within a few thousand years. This pattern repeats across the globe with unsettling consistency.

In Australia, humans arrived around 65,000 years ago, and within 20,000 years, the continent’s megafauna was largely extinct. When humans reached North America approximately 15,000 years ago, the extinction wave followed within 2,000 years. Madagascar’s giant lemurs, elephant birds, and hippos all vanished within 1,000 years of human colonization around 2,000 years ago.

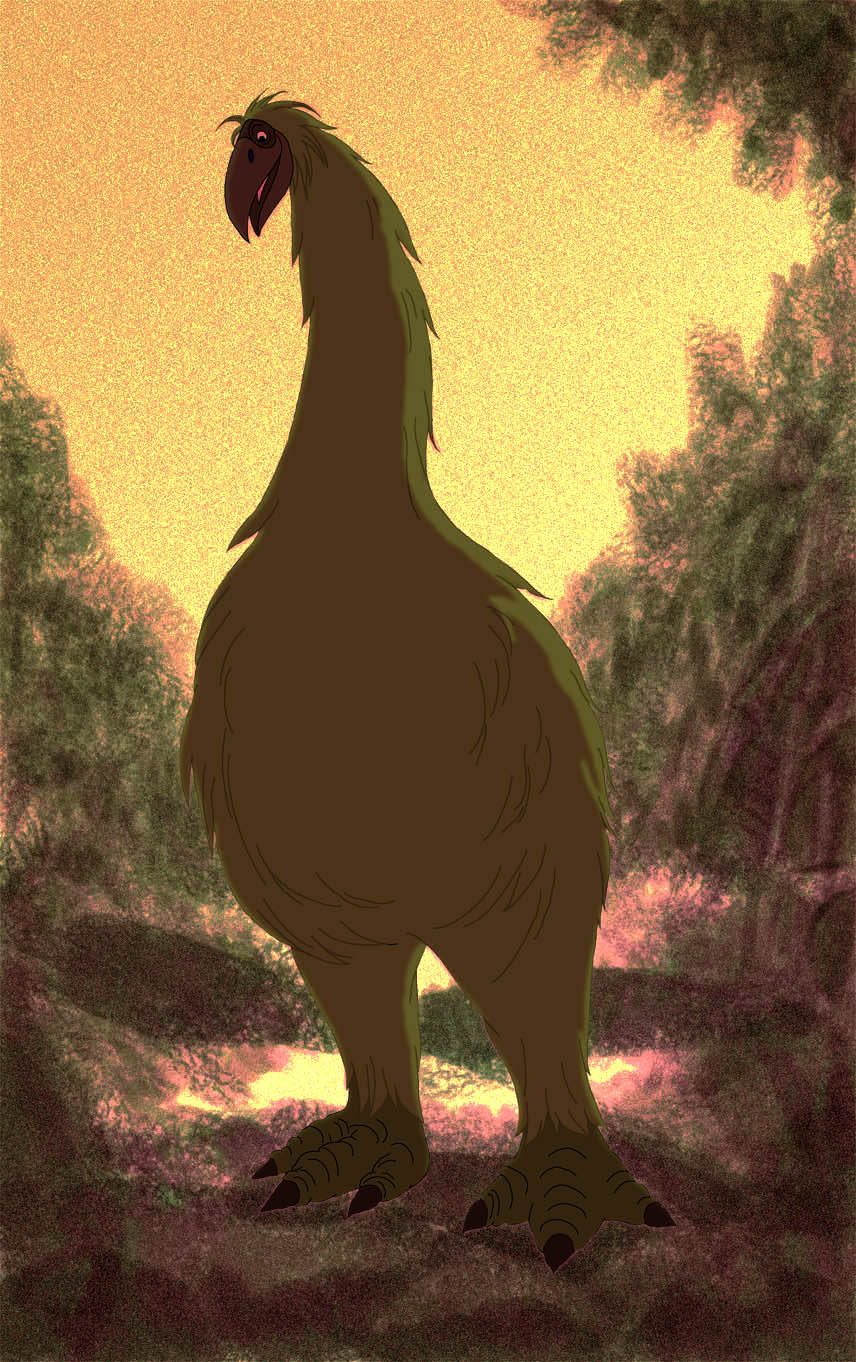

The Pacific islands tell the most dramatic story. When Polynesian settlers reached New Zealand just 700 years ago, the flightless moa birds – some standing 12 feet tall – were completely extinct within 300 years. Similar patterns emerged across dozens of Pacific islands, where human arrival meant immediate doom for large native species.

The Overkill Hypothesis Explained

The overkill hypothesis, championed by paleontologist Paul Martin, suggests that skilled human hunters systematically drove megafauna to extinction. Early humans possessed sophisticated hunting technologies, including spears, atlatls, and coordinated group tactics that made them devastatingly effective predators. These ancient hunters targeted large animals because they provided the most meat with the least effort.

Martin’s theory explains why extinction patterns followed human migration so precisely. As human populations expanded and spread across continents, they encountered naive megafauna that had never faced human predators. These animals lacked the instinctual fear and defensive behaviors needed to survive encounters with intelligent, tool-using hunters.

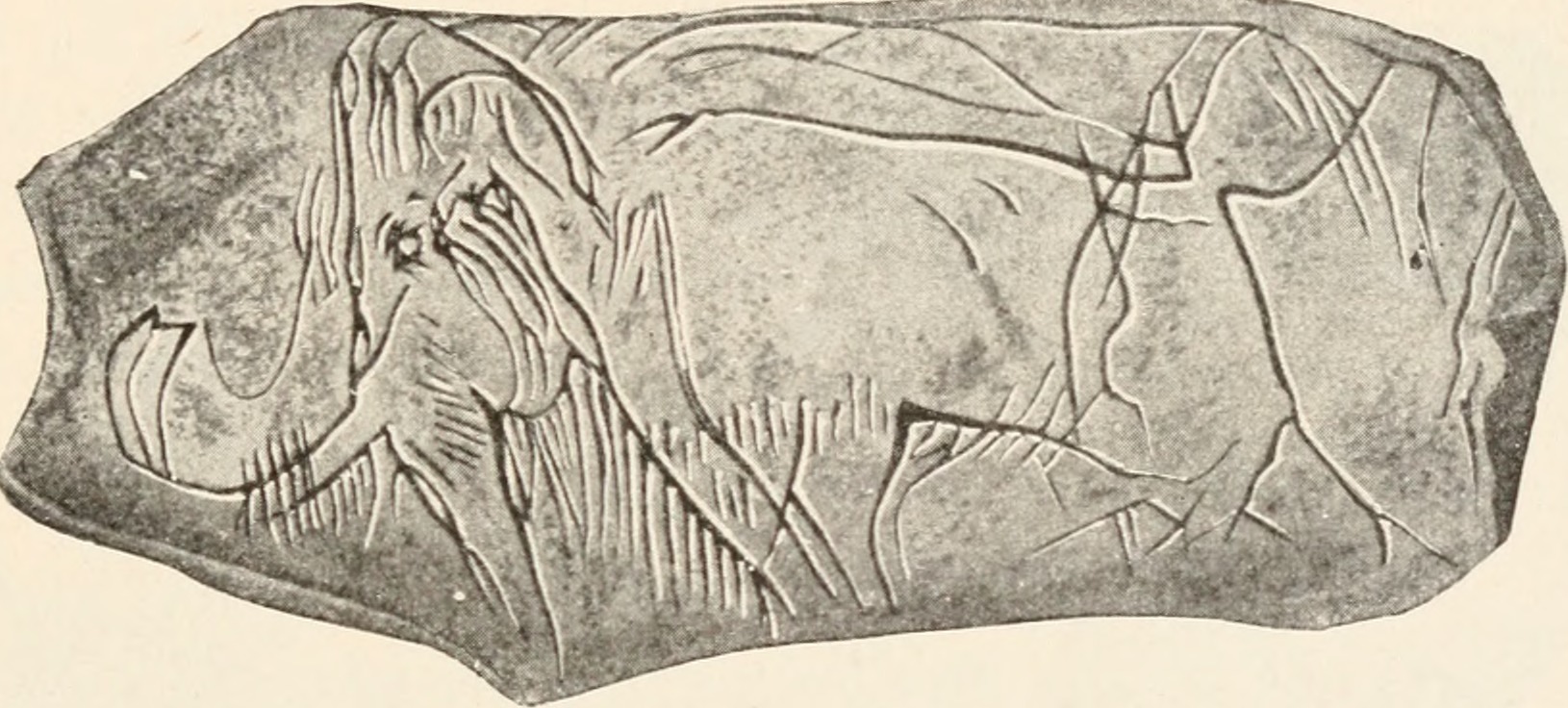

The hypothesis gains support from archaeological sites across North America, where mammoth bones bearing cut marks and spear points tell stories of successful hunts. Sites like Blackwater Draw in New Mexico and Murray Springs in Arizona preserve evidence of humans butchering freshly killed mammoths, suggesting these hunts were regular occurrences rather than rare events.

Climate Change: The Natural Suspect

Climate change presents a compelling alternative explanation for megafauna extinction. The end of the last ice age brought dramatic environmental shifts, including rising temperatures, changing precipitation patterns, and habitat transformation. These changes could have stressed megafauna populations beyond their breaking point.

As glaciers retreated, vast grasslands that supported herds of mammoths and other grazers gave way to forests. This habitat loss would have been particularly devastating for species adapted to open, cold environments. The warming climate also brought new diseases and parasites that could have decimated populations with no natural immunity.

Temperature fluctuations during this period were severe and rapid. Ice core data reveals that temperatures could swing by 10°C within decades, creating environmental chaos that even adaptable species might struggle to survive. Such dramatic changes would have disrupted food webs, breeding cycles, and migration patterns that megafauna had relied upon for millennia.

The Smoking Gun Evidence

Archaeological evidence supporting human involvement continues to mount. Kill sites across North America preserve mammoth skeletons with stone spear points embedded in their bones, clear evidence of human hunting. The Clovis culture, known for their distinctive fluted projectile points, appears in the archaeological record just as megafauna begin disappearing.

Butchery marks on bones tell detailed stories of how humans processed these massive carcasses. Cut marks on mammoth ribs show where humans removed meat, while fractured bones reveal how they extracted nutrient-rich marrow. These sites often contain the remains of multiple animals, suggesting organized hunting expeditions rather than opportunistic scavenging.

The precision of these hunts is remarkable. At the Lehner site in Arizona, researchers found remains of 13 mammoths killed over several years, all showing evidence of human butchery. The hunters clearly understood mammoth behavior, anatomy, and the most effective killing techniques – knowledge that would have made them formidable predators.

Critiques and Counterarguments

The overkill hypothesis faces significant challenges from critics who question whether small human populations could have driven such massive extinctions. Conservative estimates suggest that human populations in North America numbered only in the hundreds of thousands – seemingly too few to hunt millions of megafauna to extinction.

Mathematical models raise doubts about the timeline proposed by overkill advocates. Some researchers argue that even intensive hunting by growing human populations would have required many more millennia to cause complete extinction. The rapid nature of megafauna disappearance suggests other factors must have been involved.

Critics also point out that many megafauna species survived in regions where humans were present for thousands of years before going extinct. If humans were such effective killers, why did it take so long for extinctions to occur in some areas? This delayed extinction pattern suggests more complex causes than simple overhunting.

The Hyperdisease Theory

A fascinating alternative suggests that diseases carried by humans or their domesticated animals triggered megafauna extinctions. The hyperdisease theory proposes that pathogens spread rapidly through naive megafauna populations, causing catastrophic die-offs that made species vulnerable to other stresses.

Humans arriving in new continents would have brought novel pathogens that local wildlife had never encountered. Without natural immunity, these diseases could have swept through megafauna populations like wildfire. Modern examples include the devastating impacts of introduced diseases on island species, which often face extinction when exposed to mainland pathogens.

The theory explains why extinctions were so rapid and widespread. A single pathogen could have spread across entire continents within decades, affecting multiple species simultaneously. This scenario wouldn’t require massive human populations or intensive hunting – just the introduction of a deadly disease that indigenous fauna couldn’t survive.

Habitat Transformation and Human Impact

Beyond direct hunting, humans transformed landscapes in ways that may have doomed megafauna. Early humans used fire as a tool to clear vegetation, drive game, and create favorable hunting conditions. This practice, known as fire-stick farming, fundamentally altered ecosystems across continents.

Repeated burning converted forests into grasslands and grasslands into different types of vegetation. While some species benefited from these changes, many megafauna found their preferred habitats disappearing. Large browsers that depended on specific plant communities would have struggled as humans reshaped the botanical landscape.

The cumulative impact of habitat modification may have been more devastating than direct hunting. Even small changes in vegetation could have reduced carrying capacity for large herbivores, making populations vulnerable to other stresses. This environmental pressure, combined with hunting and climate change, created a perfect storm for extinction.

Island Extinctions: The Clearest Evidence

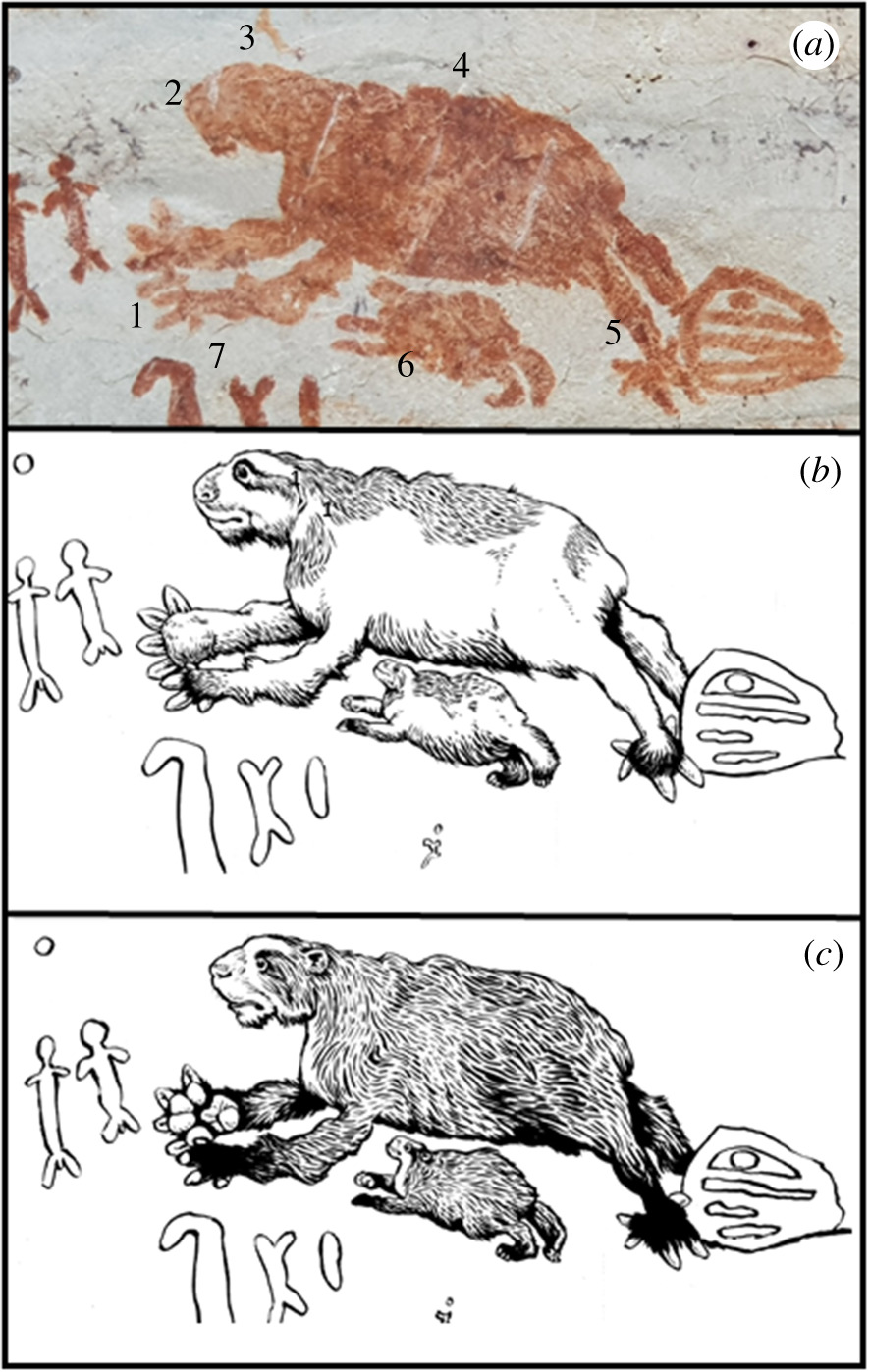

Island extinctions provide the strongest evidence for human-caused megafauna loss. When humans reached Madagascar around 2,000 years ago, the island was home to elephant birds standing 10 feet tall and weighing 1,000 pounds. Within 1,000 years, these giants were extinct, along with giant lemurs, Malagasy hippos, and numerous other large species.

The pattern repeats across the Pacific with stunning consistency. New Zealand’s moa birds, some of the largest birds that ever lived, vanished within 300 years of Polynesian arrival. Hawaii lost its flightless geese and giant eagles shortly after human colonization. The Caribbean islands saw the extinction of giant ground sloths and other megafauna following human settlement.

Islands provide natural laboratories for studying extinction because they’re isolated systems with clear timelines. The rapid disappearance of island megafauna immediately following human arrival creates compelling evidence for human causation. These extinctions happened too quickly to be explained by gradual climate change or disease spread.

The Role of Domesticated Animals

Domesticated animals that accompanied human migrations may have played crucial roles in megafauna extinction. Dogs, the first domesticated animals, were formidable hunting partners that could track, chase, and harass large prey. Archaeological evidence shows that humans and dogs worked together to hunt mammoths, making them a deadly combination.

Later domesticated animals like pigs, goats, and cattle competed with native megafauna for resources. These introduced species often thrived in their new environments, outcompeting indigenous animals for food and habitat. On islands, introduced pigs destroyed ground-nesting bird colonies, while goats stripped vegetation that native species depended upon.

The diseases carried by domesticated animals may have been equally devastating. Cattle, pigs, and other livestock harbor pathogens that can jump to wild species. When these diseases encountered naive populations with no natural immunity, the results could be catastrophic. This biological warfare may have softened up megafauna populations for the final blow.

Survival Stories: Why Some Made It

Not all megafauna succumbed to extinction, and their survival stories offer clues about what went wrong for their less fortunate relatives. African megafauna like elephants, rhinoceros, and hippos survived because they evolved alongside humans for millions of years. These species developed behaviors and instincts that helped them avoid human predators.

Bison in North America came perilously close to extinction but survived in small populations. Their survival demonstrates that megafauna could coexist with humans under certain conditions. Bison herds were so massive that even intensive hunting couldn’t immediately drive them extinct, though European colonization nearly finished the job.

Some megafauna survived in refugia – isolated areas where human pressure was reduced. Woolly mammoths persisted on Wrangel Island until 4,000 years ago, thousands of years after their mainland cousins disappeared. These island populations show that megafauna could survive when protected from human hunting pressure.

Modern Parallels and Lessons

Today’s ongoing extinction crisis mirrors many patterns seen in megafauna loss. Large animals remain the most vulnerable to human activities, with elephants, rhinoceros, and great apes facing severe population declines. The same combination of hunting pressure, habitat loss, and human expansion that doomed ice age giants threatens modern megafauna.

Conservation efforts provide hope and demonstrate that extinction isn’t inevitable. Successful programs have brought species like the California condor, black-footed ferret, and Arabian oryx back from the brink of extinction. These successes show that with sufficient effort and resources, humans can reverse the damage we’ve caused.

The lessons from megafauna extinction extend beyond conservation. They remind us that human activities have profound and lasting impacts on natural systems. Understanding how our ancestors triggered these extinctions helps us recognize and address similar threats facing today’s wildlife. Every species we save today represents a victory against the same forces that claimed the ice age giants.

The Verdict: Multiple Culprits

The evidence suggests that no single factor caused megafauna extinction. Instead, multiple stressors worked together to push these magnificent creatures over the edge. Climate change weakened populations and altered habitats, human hunting provided direct mortality pressure, and diseases introduced by humans or their animals delivered the final blow.

This multi-factor explanation makes the most sense given the available evidence. Different regions experienced different combinations of these stressors, explaining why extinction patterns varied across continents. In some areas, hunting may have been the primary driver, while in others, habitat loss or disease played larger roles.

The timing of extinctions supports this complex causation model. Most megafauna extinctions occurred during periods of environmental stress when multiple pressures converged. These species had survived previous climate changes and other challenges, but the addition of human-related stressors proved too much to overcome.

The disappearance of ice age megafauna represents one of the most dramatic ecological transformations in Earth’s history. While we may never know exactly how much responsibility humans bear for these extinctions, the evidence strongly suggests our ancestors played a significant role. This realization carries profound implications for how we approach conservation today. The same intelligence and technology that made our ancestors such effective hunters now gives us the power to protect rather than destroy. The question isn’t whether we can prevent future extinctions, but whether we will choose to do so. What would our world look like today if those ancient giants had survived alongside us?