Picture a prehistoric world where death comes not from titanic jaws or crushing feet, but from a creature no bigger than a turkey – yet armed with curved talons that could pierce flesh like knives. For decades, Hollywood painted these killers as scaly monsters the size of bears, prowling in deadly packs. But the truth about Cretaceous raptors is far more fascinating than fiction. They were feathered, warm-blooded predators that bridged the gap between dinosaurs and birds in ways that continue to rewrite paleontology textbooks.

The Turkey-Sized Terror that Changed Everything

Velociraptors weren’t the six-foot giants of blockbuster films – they weighed 31-43 pounds and measured about 1.5 to 2.07 meters long. The real animal was about the size of a Thanksgiving turkey, making them surprisingly small for creatures that have terrorized movie audiences worldwide. Yet this compact size was actually their greatest weapon.

These waist-high predators roamed central and eastern Asia between about 74 million and 70 million years ago, during the late Cretaceous period. Hardly the vicious pack hunters depicted in Jurassic Park, these feathered animals were more similar to modern birds of prey. Their lightweight build and powerful legs made them deadly efficient hunters in ways that would make any eagle proud.

Feathers, Not Scales: The Shocking Truth

In 2007, the discovery of quill knobs on a Velociraptor fossil proved that this dinosaur had long feathers attaching from its second finger and up its arms. This revolutionary finding shattered the old image of scaled reptilian monsters forever. However, they would have looked more like a bird, fully feathered – think of a deadly, flightless hawk with teeth instead of a beak.

The 2007 study hypothesized that Velociraptor’s feathers might have been an evolutionary leftover from smaller ancestors that could fly, or they might have served to attract mates, shield nests from the cold, or maneuver while running. These weren’t just decorative plumes but functional features that helped these predators survive in harsh Cretaceous environments. The discovery changed how we visualize these ancient hunters completely.

The Famous Sickle Claw: Weapon of Precision

Velociraptors are often likened to birds of prey such as eagles and hawks because of the long claw protruding from the second toe of each foot. Although scientists once theorized the claws may have been used for slashing, most now believe that the dinosaur used them to pierce and pin down prey as hawks do. This “killing claw” became the signature weapon that defined the entire raptor family.

The sickle claw did penetrate the abdominal wall, it was unable to tear it open, indicating that the claw was not used to disembowel prey as once believed. This model, known as the “raptor prey restraint” (RPR) model of predation, proposes that dromaeosaurids killed their prey in a manner very similar to extant accipitrid birds of prey: by leaping onto their quarry, pinning it under their body weight, and gripping it tightly with the large, sickle-shaped claws. Like accipitrids, the dromaeosaurid would then begin to feed on the animal while still alive, until it eventually died from blood loss and organ failure. This hunting method was far more sophisticated than simple slashing attacks.

Pack Hunters or Solitary Stalkers?

Although many isolated fossils of Velociraptor have been found in Mongolia, none were closely associated with other individuals. Therefore, while Velociraptor is commonly depicted as a pack hunter, as in Jurassic Park, there is only limited fossil evidence to support this theory for dromaeosaurids in general and none specific to Velociraptor itself. This revelation dismantles one of cinema’s most enduring dinosaur myths.

They found evidence of intraspecies aggression between raptors (one raptor killed another) and also through phylogenetic inference concluded these theropods were “solitary hunters or, at most, foraged in loose associations.” Frederickson et al. found the isotope ratios in young and adult Deinonychus teeth were supportive of asocial animals and were, in fact, very similar to crocodilians. This indicates Deinonychus did not feed their young, so they may not have lived in social groups or hunted in packs.

The evidence suggests these predators were more like modern crocodiles – coming together opportunistically around carcasses but not truly cooperating in organized hunts.

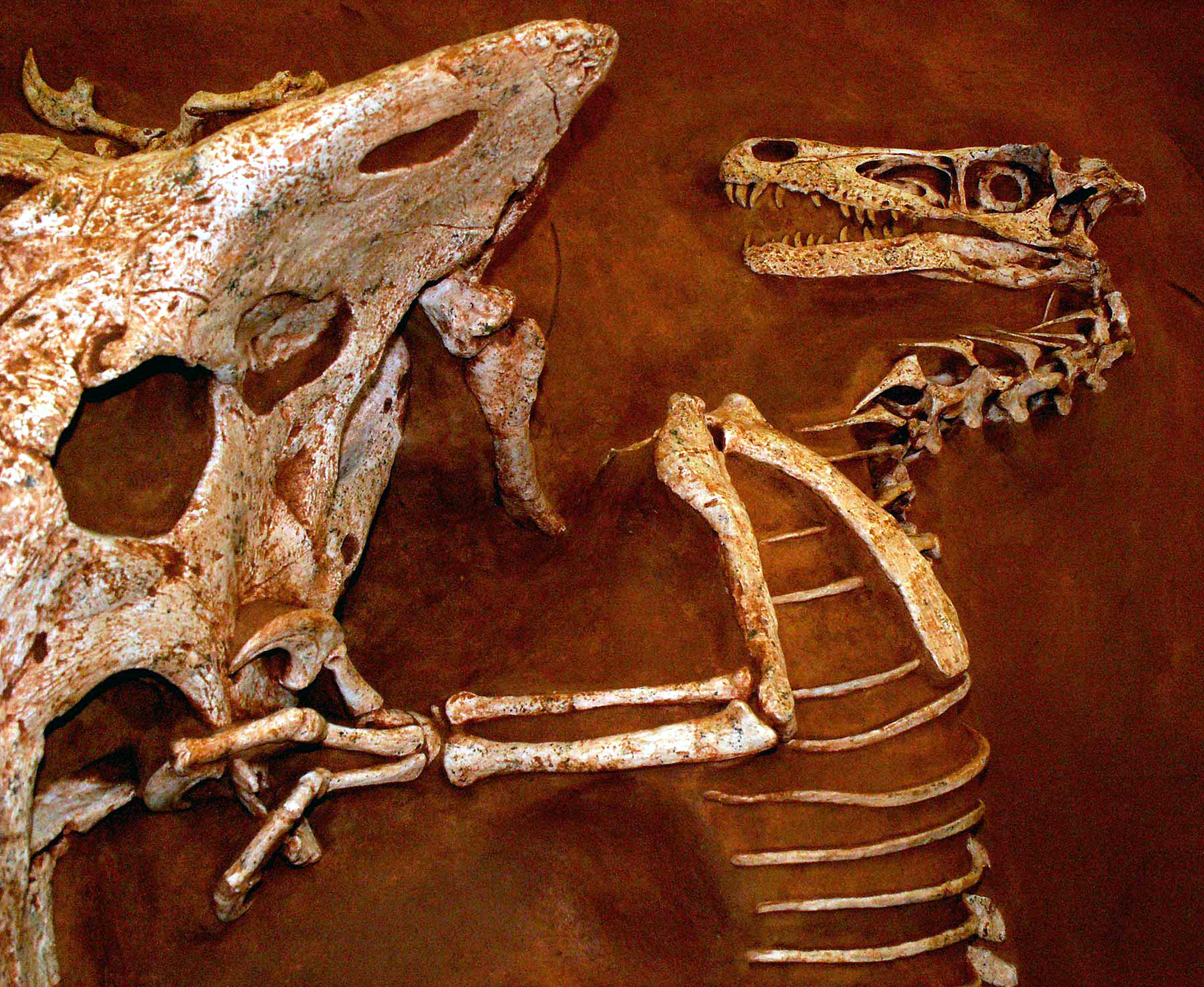

The Fighting Dinosaurs: A Moment Frozen in Time

The famous fighting dinosaurs specimen from Mongolia shows Velociraptor and the early ceratopsian Protoceratops engaged in battle. The Velociraptor’s deadly foot claw is in the Protoceratops’s throat, and the Velociraptor’s arm is crushed in the Protoceratops’s mouth. It appears they were preserved in this pose because they were buried by a sandstorm or collapsing sand dune in the middle of their struggle.

This extraordinary fossil tells a dramatic story of predator and prey locked in mortal combat. David says it’s hard to determine why the animals were fighting. Was the Velociraptor hunting the Protoceratops? If so, it was probably desperate or inexperienced. The specimen provides rare behavioral evidence that these raptors were willing to take on dangerous prey when circumstances demanded it.

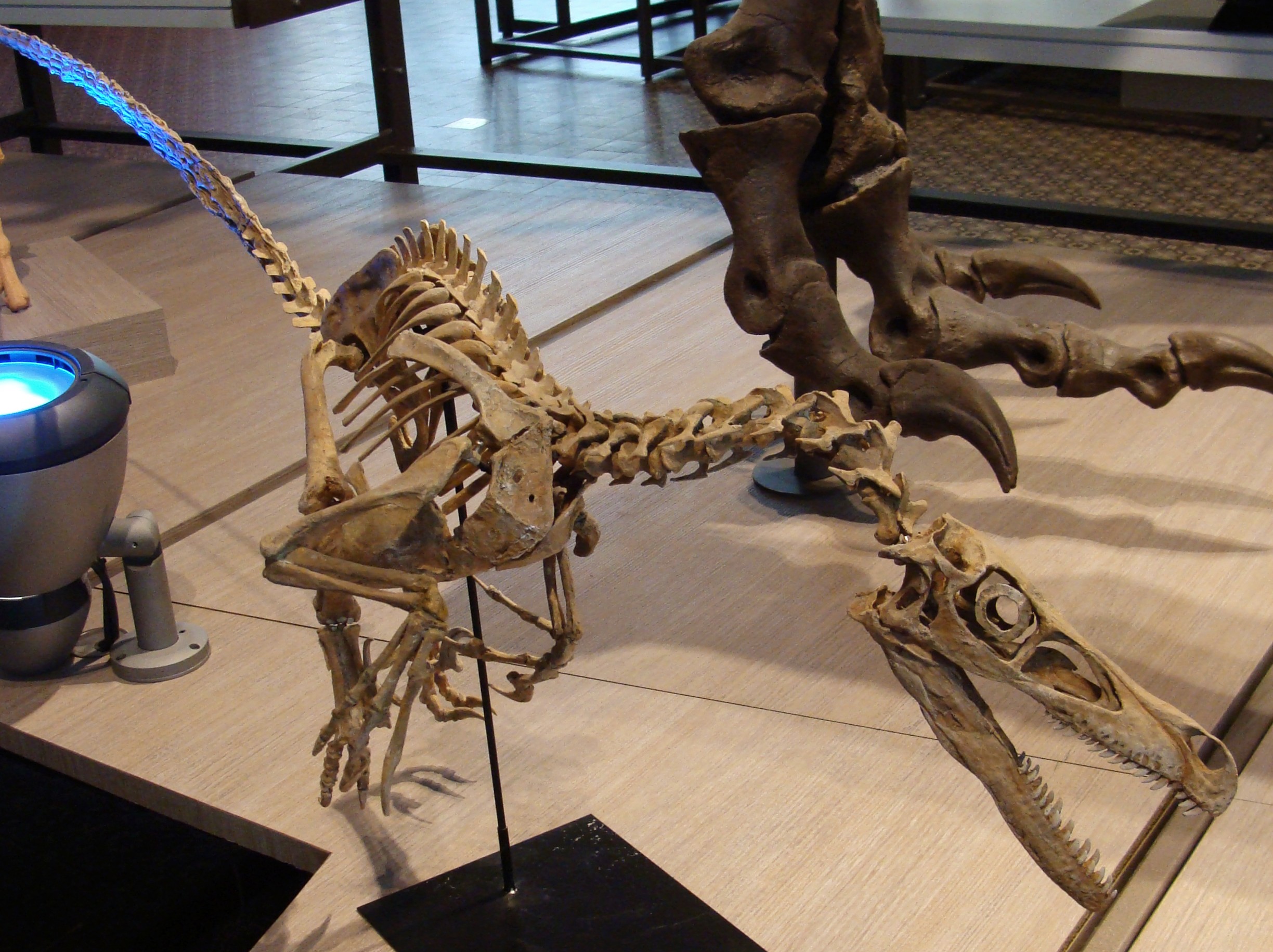

Giants Among Raptors: The Larger Cousins

While Velociraptor remained relatively small, other members of the raptor family reached truly intimidating sizes. Utahraptor is the largest known member of the family Dromaeosauridae, measuring about 6–7 metres (20–23 ft) long and typically weighing around 500 kilograms (1,100 lb). As a heavily built, ground-dwelling, bipedal carnivore, its large size and variety of unique features have earned it attention in both pop culture and the scientific community.

Being a carnivore, Utahraptor was adapted to hunt the other animals of the Cedar Mountain Formation ecosystem such as ankylosaurs and iguanodonts. Evidence from the leg physiology supports the idea of Utahraptor being an ambush predator, in contrast to other dromaeosaurs that were pursuit predators. These giants represented a different ecological strategy – overwhelming power rather than speed and agility.

Night Hunters with Eagle Eyes

Recent research shows they had large eyes, indicative of good night vision, so they may have been nocturnal hunters. This discovery adds another layer to our understanding of raptor behavior. In 2011, scientists also theorized that these predators were nocturnal, as their scleral ring – a bony disc that reinforces the eye – was wide and would have let in enough light to see at night.

They also have forward facing eyes for good stereo vision. To accommodate their extra motor skills and superb vision, their brains were relatively larger than other dinosaurs (but still much smaller than mammal brains). These adaptations suggest raptors were sophisticated hunters capable of stalking prey in low-light conditions when many other predators would be blind.

The Intelligence Question: Clever or Instinctive?

Velociraptor also probably wasn’t as intelligent as popular culture has made it out to be. It’s true that this dinosaur had a large brain in proportion to its body, making it one of the more intelligent dinosaurs. But that’s a level of brainpower likely on par with average birds rather than the likes of chimps or parrots. The Hollywood portrayal of problem-solving geniuses was pure fiction.

The relatively large brains of dromaeosaurs enabled them to carry out these complex movements with a degree of coordination unusual among reptiles but quite expected in these closest relatives of birds. While not criminal masterminds, they possessed the cognitive abilities needed for sophisticated predatory behaviors and complex movements during hunting.

Diet and Feeding: Scavengers or Active Predators?

In 2012, Hone and colleagues published a paper that described a Velociraptor specimen with a long bone of an azhdarchid pterosaur in its gut. This was interpreted as showing scavenging behaviour. It is theorized by the authors that high bite force resistance was an adaptation towards obtaining food through scavenging more often than through active predation in Velociraptor. This suggests these predators weren’t above taking easy meals when available.

Despite the famous fossilization of a battle to the death between a Velociraptor and a much-larger Protoceratops, paleontologists believe that Velociraptors mainly preyed on small mammals and reptiles. Their diet was likely more opportunistic than previously thought, combining active hunting with scavenging when circumstances allowed.

The Modern Discoveries: New Insights from Recent Research

Recent fossil discoveries continue to expand our understanding of raptor diversity and distribution across various formations in Asia.

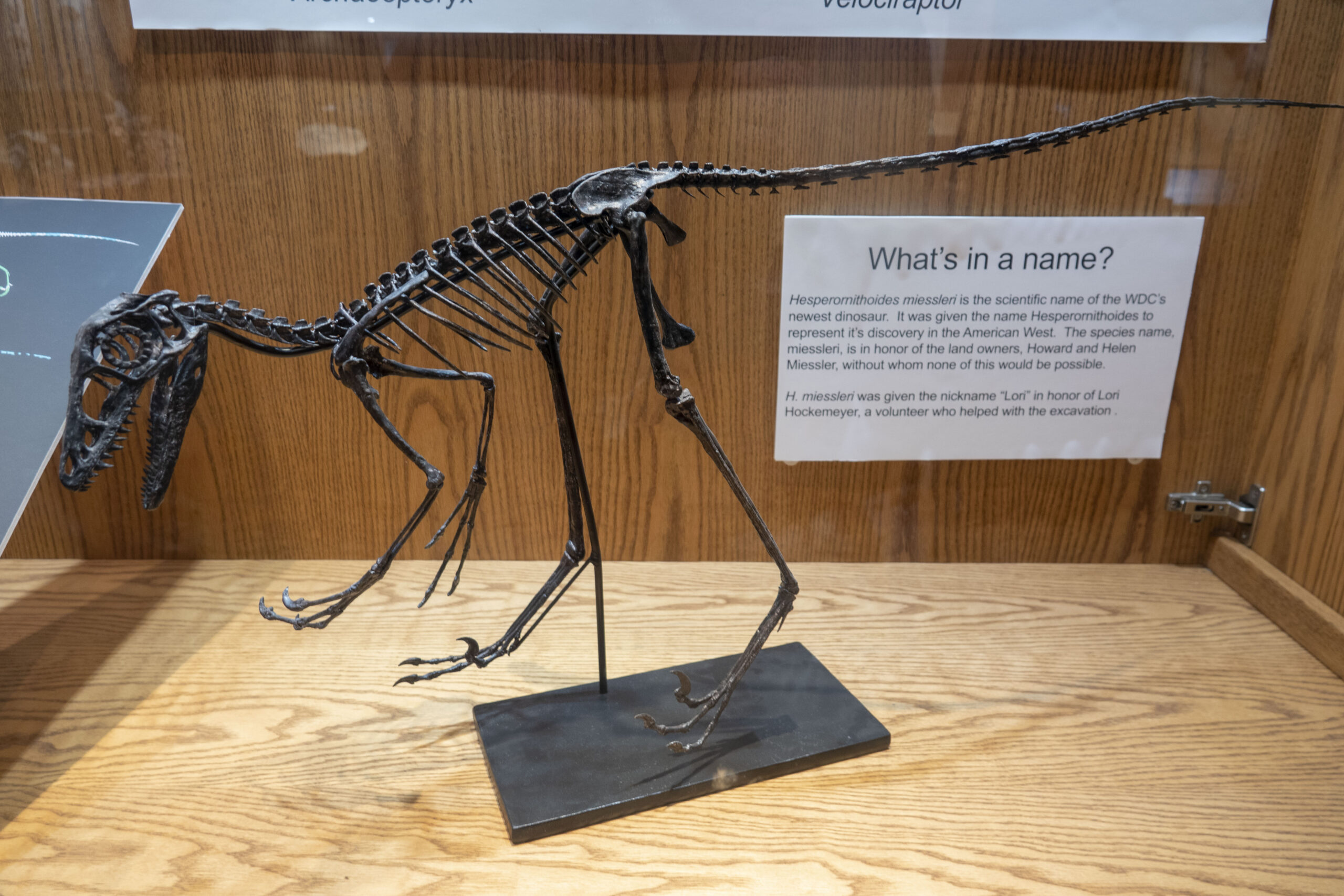

More recently, scientists discovered Velociraptor’s oldest known relative: a three-foot-long fluffy dinosaur named Hesperornithoides miessleri. Covered in feathers and sporting a sickle-shaped claw on each foot, this little hunter lived in the late Jurassic period, about 164 million to 145 million years ago. Though Hesperornithoides miessleri was apparently unable to fly, its existence suggests that dinosaurs began to evolve feathers and wing-like arms millions of years before the first birds appeared. This discovery pushes back the timeline of feather evolution significantly.

Conclusion: Separating Myth from Reality

The real story of Cretaceous raptors is far more nuanced than Hollywood’s version. These weren’t oversized pack-hunting monsters but sophisticated, feathered predators that combined bird-like intelligence with deadly precision. Velociraptor disappeared from the fossil record about 70 million years ago. A few million years later, a cataclysmic asteroid strike sparked an extinction event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs.

Yet their legacy lives on in every bird that soars overhead. From turkey-sized terrors to bear-sized giants, these remarkable predators bridged the evolutionary gap between reptiles and birds in ways that continue to amaze scientists today. The next time you watch a hawk snatch its prey with surgical precision, remember – you’re witnessing the hunting strategy perfected by raptors over 70 million years ago.

Who would have thought that the most fearsome predators of the Cretaceous were actually feathered, warm-blooded creatures more similar to birds than lizards?