Imagine a world where you could walk from New York to South Africa without crossing a single ocean. Picture vast inland deserts stretching for thousands of miles, while massive creatures roamed freely across a unified landmass. This isn’t science fiction – it’s the reality of Pangaea, the supercontinent that existed roughly 299 million to 201 million years ago, when Earth looked nothing like the planet we know today. On this colossal landmass, dinosaurs and their early relatives shared habitats without the barriers of oceans to separate them. Species could spread across entire continents, shaping ecosystems that were both diverse and interconnected. The climate, however, was harsh—ranging from scorching deserts at the interior to lush, wetter regions along the coasts. These extremes influenced how life adapted, forcing creatures to become tougher, more versatile, and ready to seize new opportunities. Pangaea wasn’t just a stage for survival—it was the testing ground for the evolutionary giants that would soon dominate the Mesozoic world.

The Formation of Pangaea: When All Lands Became One

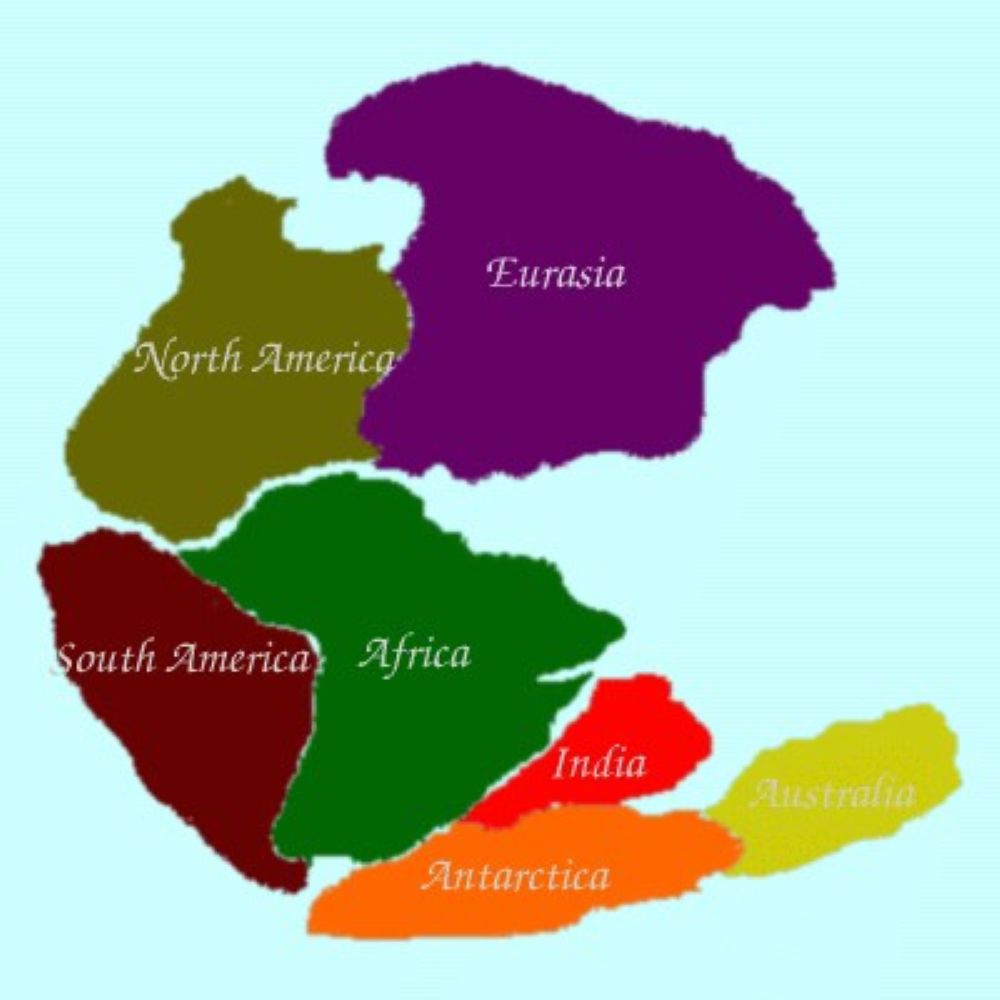

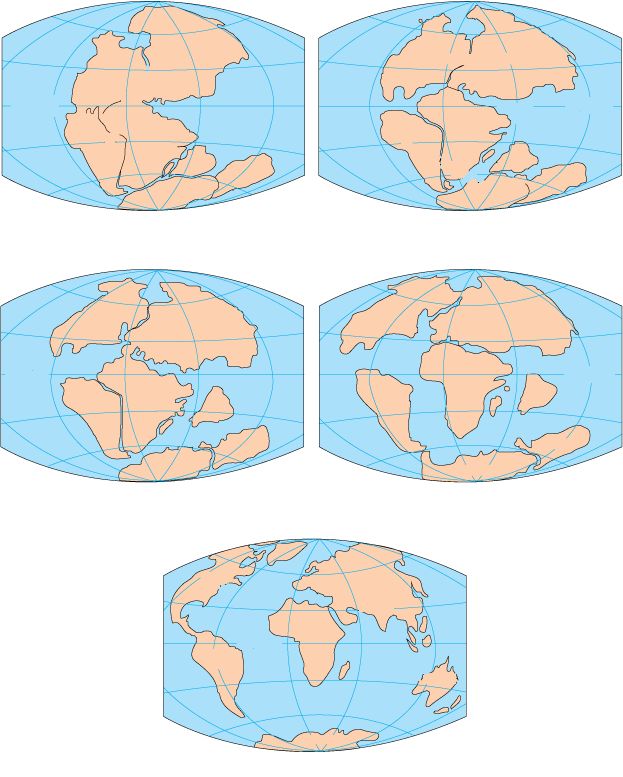

Pangaea assembled from earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous period approximately 299 million years ago. The name itself comes from ancient Greek, meaning “all the Earth,” and it perfectly captured the reality of this massive landmass. Pangaea was C-shaped, with the bulk of its mass stretching between Earth’s northern and southern polar regions. The curve of the eastern edge of the supercontinent contained an embayment called the Tethys Sea.

At that time, Earth didn’t have seven continents, but instead one giant one surrounded by a single ocean called Panthalassa. The sheer scale of this supercontinent is almost impossible to comprehend – it included virtually all of Earth’s land surface area, creating a world fundamentally different from our own.

An Extreme Climate Like No Other

Living on Pangaea would have meant experiencing some of the most extreme weather patterns in Earth’s history. The global climate during the Triassic was mostly hot and dry, with deserts spanning much of Pangaea’s interior. However, the climate shifted and became more humid as Pangaea began to drift apart. The continental interior was particularly harsh – ocean-circulation patterns kept the isolated and vast interior warm and dry. Even the Poles were ice-free.

Climate models confirm that the continental interior of Pangaea was extremely seasonal. The researchers used biological and physical data from the Moradi Formation, a region of layered paleosols (fossil soils) in northern Niger, to reconstruct the ecosystem and climate during the time period when Pangaea existed. This seasonality created a world of extremes that would have challenged any form of life attempting to survive in the interior regions.

The Rise of the Dinosaur Empire

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of life on Pangaea was witnessing the very beginning of the dinosaur age. At the beginning of the age of dinosaurs (during the Triassic Period, about 230 million years ago), the continents were arranged together as a single supercontinent called Pangea. These early dinosaurs emerged in a world dramatically different from the fragmented continents they would later dominate.

The evolution of dinosaurs and the first mammals began in the late Triassic, starting around 230 million years ago. Among the first dinosaurs was the two-footed carnivore Coelophysis, which was about 10 feet (3 meters) long, weighed about 33-44 pounds (15-20 kilograms), and probably fed on small reptiles and amphibians. It showed up about 225 million years ago. The unified landmass provided these early dinosaurs with unprecedented opportunities for expansion and evolution.

Migration Highways Across a Unified World

One of the most significant advantages of living on Pangaea was the ease of movement across vast distances. Land bridges between regions provided critical migration pathways for different species. These bridges allowed species, including early dinosaurs, to move across the continent and adapt to local environments. These migration corridors were crucial for the development of diverse ecosystems within the supercontinent, as species could spread quickly to favorable regions.

The transport of plant and animal species into new territories is facilitated by their proximity. Seeds are more easily transported by wind and animals if they need not cross barriers such as oceans, as they must today. This created a world where evolution could occur on a truly continental scale, with genetic material flowing across thousands of miles without the barriers that separate species today.

Lush Tropical Forests in an Otherwise Desert World

Despite the harsh interior conditions, certain regions of Pangaea supported incredibly rich ecosystems. Coal deposits found in the United States and Europe reveal that parts of the ancient supercontinent near the equator must have been a lush, tropical rainforest, similar to the Amazonian jungle. (Coal forms when dead plants and animals sink into swampy water, where pressure and water transform the material into peat, then coal.) “The coal deposits are essentially telling us that there was plentiful life on land”.

These tropical regions would have been like islands of biodiversity in an otherwise arid landscape. The contrast between the desert interior and these lush coastal and equatorial zones created a world of dramatic ecological diversity, where life thrived in scattered oases of moisture and abundance.

The Permian Extinction: A World Reborn

Life on Pangaea began under the shadow of one of the most catastrophic events in Earth’s history. The start of the Triassic period was a desolate time in Earth’s history. Something – a bout of violent volcanic eruptions, climate change, or perhaps a fatal run-in with a comet or asteroid – had triggered the extinction of over 90 percent of marine species and about 70 percent of terrestrial vertebrate species. Life that survived the so-called Great Dying repopulated the planet, diversified into freshly exposed ecological niches, and gave rise to new creatures, including rodent-size mammals and the first dinosaurs.

This mass extinction created a blank slate for evolution, allowing surviving species to rapidly diversify and fill empty ecological niches. The unified nature of Pangaea meant that successful survivors could quickly spread across the entire landmass, establishing global populations in ways impossible on our fragmented modern world.

Ocean Life in the Age of Panthalassa

While land life was adapting to the challenges of Pangaea, the surrounding ocean – Panthalassa – teemed with its own remarkable creatures. The oceans teemed with the coiled-shelled ammonites, mollusks, and sea urchins that survived the Permian extinction and were quickly diversifying. The first corals appeared, though other reef-building organisms were already present. Giant reptiles such as the dolphin-shaped ichthyosaurs and the long-necked and paddle-finned plesiosaurs preyed on fish and ancient squid.

The single global ocean created unique circulation patterns that affected both marine and terrestrial life. Without the complex system of separate oceans we have today, Panthalassa’s currents operated on a truly global scale, distributing heat and nutrients in ways that profoundly influenced climate patterns across Pangaea.

Provincial Life Despite Global Connection

Surprisingly, even with all land connected, life on Pangaea wasn’t uniformly distributed. There is evidence that many Pangaean species were provincial, with a limited geographical range, despite the absence of geographical barriers. This may be due to the strong variations in climate by latitude and season produced by the extreme monsoon climate. For example, cold-adapted pteridosperms (early seed plants) of Gondwana were blocked from spreading throughout Pangaea by the equatorial climate, and northern pteridosperms ended up dominating Gondwana in the Triassic.

This provincialism shows that even on a unified continent, climate and environmental conditions created invisible barriers that were just as effective as oceans in preventing species migration. The extreme seasonal variations and temperature gradients across Pangaea’s massive expanse created distinct biogeographic regions that fostered unique evolutionary paths.

The Carnian Pluvial Episode: A Climate Revolution

One of the most dramatic events during Pangaea’s existence was a sudden shift in global climate that changed the trajectory of life on Earth. The CPE of the earliest Late Triassic marks a global increase in effective precipitation (precipitation minus evaporation) for at least 1–2 Myr, causing major floristic and faunal turnovers and possibly triggering the rise of the dinosaurs. This period, known as the Carnian Pluvial Episode, transformed vast arid regions into more hospitable environments.

Around 234-232 Ma, a 10 Myr eccentricity maximum caused a paludification of Pangaea and a reduction in the size of arid climatic zones. This dramatic climate shift created new opportunities for life to flourish in previously barren regions, potentially providing the environmental pressure that drove dinosaur evolution and diversification.

The Beginning of the End: Pangaea’s Breakup

As successful as life became on Pangaea, the supercontinent wasn’t destined to last forever. Pangaea began to break up toward the end of the Triassic, first along the boundary between North America and Africa. The original continental boundary wasn’t exactly reproduced; instead, North America gained a chunk of land that today includes Florida and nearby parts of the southeastern United States. As the two continents began to move in different directions, long narrow rift valleys formed along the seam.

Pangaea’s breakup had the opposite effect: more shallow water habitat emerged as overall shoreline length increased, and new habitats were created as channels between the smaller landmasses opened and allowed warm and cold ocean waters to mix. On land, the breakup separated plant and animal populations, but life-forms on the newly isolated continents developed unique adaptations to their new environments over time, and biodiversity increased.

When we think about life on Pangaea, we’re glimpsing a world that operated by completely different rules than our own. It was a place where a single species could potentially inhabit an area larger than all of today’s continents combined, where climate extremes shaped evolution in ways we can barely imagine, and where the first stirrings of the dinosaur age began to transform the planet. The legacy of this ancient supercontinent lives on in the distribution of species, the similarities we see in fossils across different continents, and the very DNA of creatures that trace their origins back to those distant days when all the world was one.

How different might life have been if Pangaea had never broken apart?