What if the secret to one of evolution’s greatest success stories wasn’t about being the strongest or the smartest, but simply about staying warm? The rise of dinosaurs from humble beginnings to planetary dominance is a tale of survival against impossible odds, where feathers proved mightier than fangs. In the aftermath of the Permian-Triassic extinction—the deadliest event in Earth’s history—life struggled to rebuild. Harsh climates, unstable ecosystems, and fierce competition defined the Triassic world. Yet small, warm-blooded proto-dinosaurs had a hidden edge: insulation and adaptability that allowed them to outlast many rivals. As reptiles and amphibians faltered, dinosaurs seized new opportunities, spreading across the supercontinent of Pangaea. Their triumph wasn’t overnight, but step by step, these survivors set the stage for a dynasty that would dominate the planet for over 160 million years.

The Great Dying Sets the Stage

The Permian–Triassic extinction event, colloquially known as the Great Dying, was an extinction event that occurred approximately 252 million years ago, at the boundary between the Permian and Triassic geologic periods. It is Earth’s most severe known extinction event, with the extinction of 57% of biological families, 62% of genera, 81% of marine species, and 70% of terrestrial vertebrate species. This catastrophe was so severe that it nearly wiped life from Earth entirely.

The scientific consensus is that the main cause of the extinction was the flood basalt volcanic eruptions that created the Siberian Traps, which released sulfur dioxide and carbon dioxide. The aftermath left a planet eerily quiet, with vacant ecosystems waiting to be filled. Land vertebrates took an unusually long time to recover from the P–Tr extinction; paleontologist Michael Benton estimated the recovery was not complete until 30 million years after the extinction, i.e. not until the Late Triassic, when the first dinosaurs had risen from bipedal archosaurian ancestors.

Dinosaurs Emerge in a Changed World

The Triassic Period (252-201 million years ago) began after Earth’s worst-ever extinction event devastated life. The Permian-Triassic extinction event, also known as the Great Dying, took place roughly 252 million years ago. Into this recovering world stepped the ancestors of what would become the most successful group of land animals ever to walk the Earth.

It was around 230-233 million years ago that the first dinosaurs appear in the fossil record. These dinosaurs were small, bipedal creatures that would have darted across the variable landscape. Think of them not as the mighty T. rex or towering sauropods of later periods, but as agile, crow-sized creatures scurrying through a landscape still healing from catastrophe.

Small Players in a Crowded Field

The early dinosaurs weren’t the dominant force we might expect. These early dinosaurs were mostly small, lightly built two-legged carnivores, including animals such as Coelophysis and its close relatives. Dinosaurs were not a major part of Late Triassic faunas. Instead, the Triassic world was ruled by other reptilian groups.

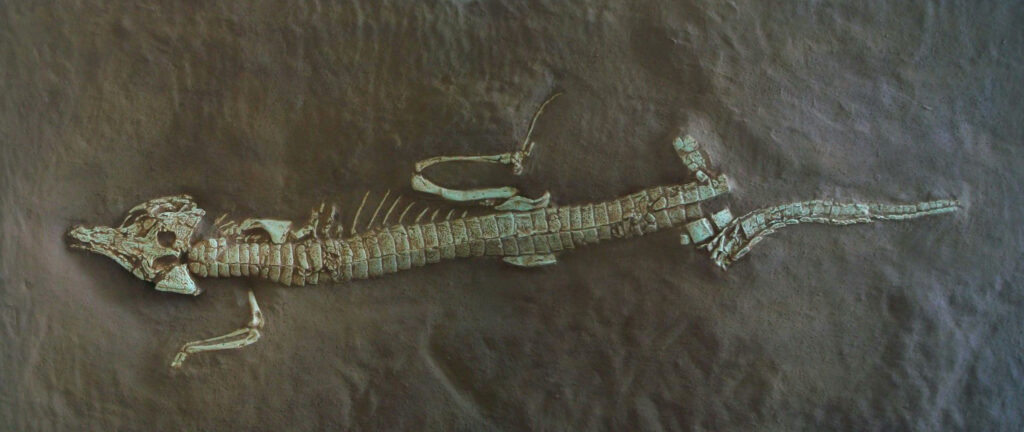

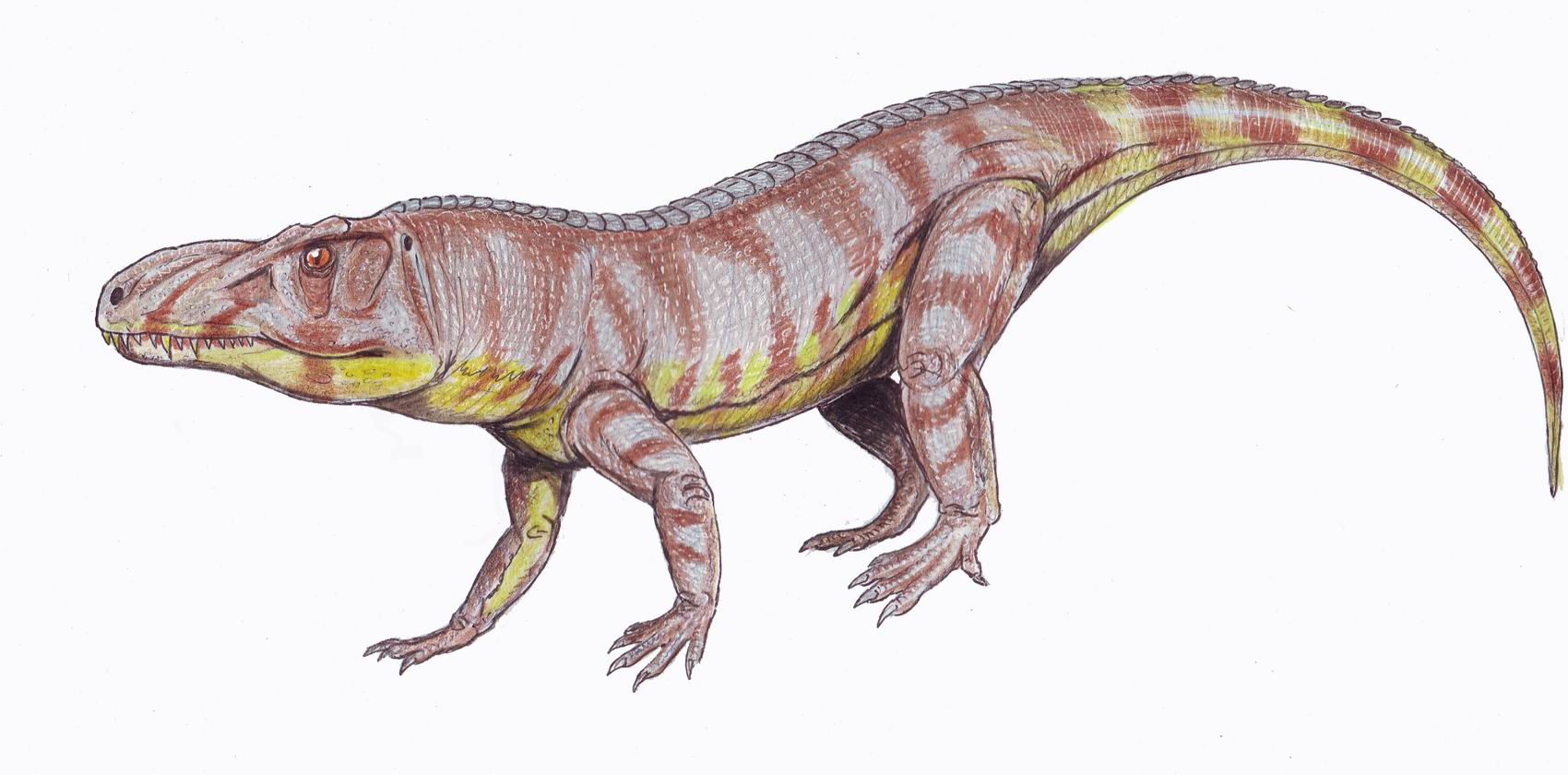

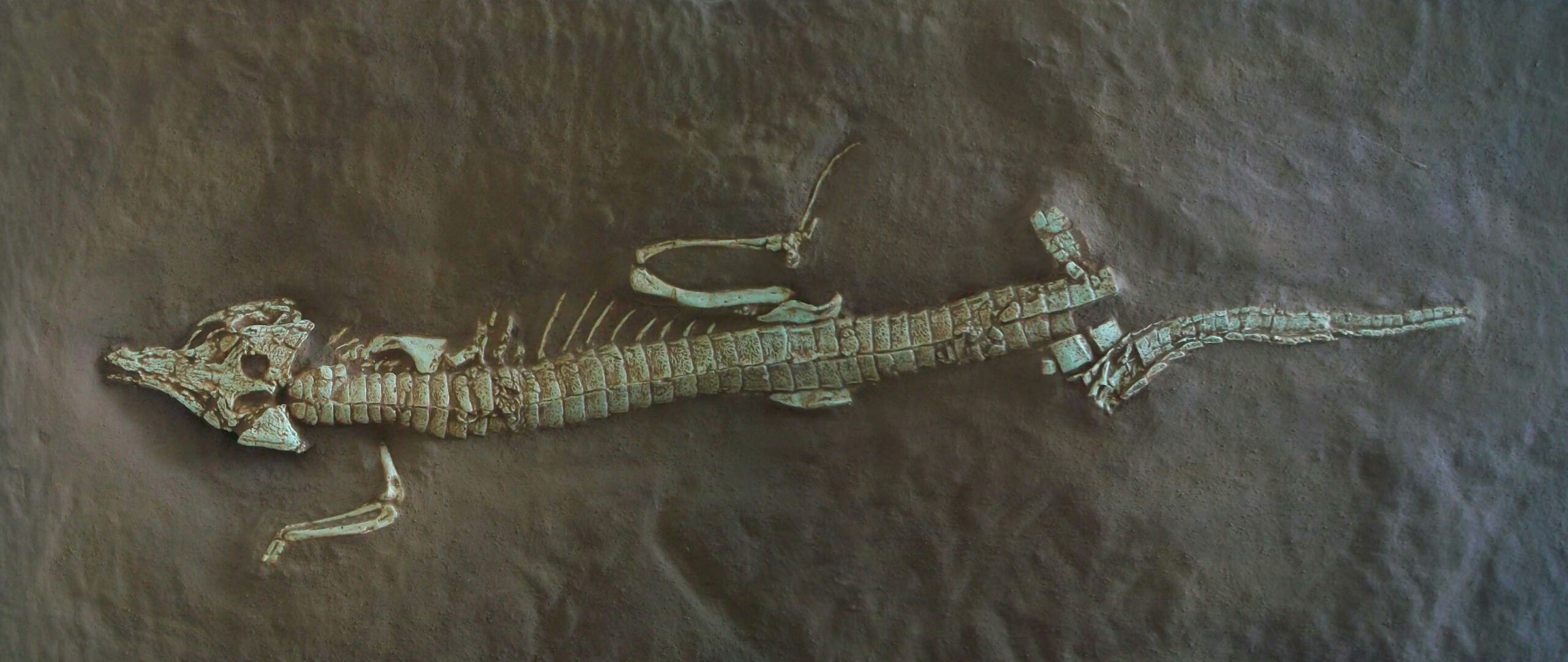

Pseudosuchians were far more ecologically dominant in the Triassic, including large herbivores (such as aetosaurs), large carnivores (“rauisuchians”), and the first crocodylomorphs. “rauisuchians” (formally known as paracrocodylomorphs) were the keystone predators of most Triassic terrestrial ecosystems. These massive crocodile-like creatures ruled the warm lowlands while early dinosaurs remained relatively minor players in the ecological drama.

The Secret Weapon: Feathers in the Cold

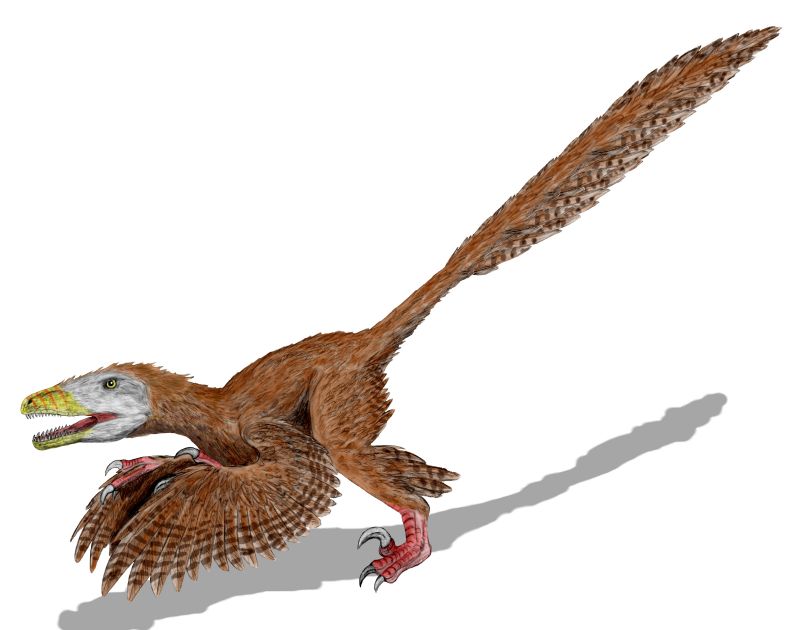

While their competitors basked in tropical warmth, early dinosaurs were developing something revolutionary. Early dinosaurs had developed insulating coats of feathers to access the rich vegetation found closer to the poles. This adaptation may have led them to survive the extinction and populate the Earth during the Jurassic.

We infer through phylogenetic bracket analysis that dinosaurs were primitively born with feathers, not for flying, but most likely for insulation. The paper showed that the feathers, or protofeathers, were filamentous integumentary coverings, which enabled the dinosaurs to access rich deciduous and evergreen Arctic vegetation, even under freezing winter conditions. These weren’t the complex flight feathers we see in modern birds, but simple, downy coverings that trapped warm air close to their bodies.

Living on the Edge of the World

Dinosaurs first appeared in temperate southerly latitudes roughly 230-233 million years ago during the Triassic period, back when Earth’s continents were still joined together to form a supercontinent called Pangea. By around 214 million years ago, dinosaurs had spread northwards toward Arctic regions, but they still remained a minor group compared to other species on Earth.

This northward migration wasn’t accidental – it was evolutionary genius. The researchers of this new study were exploring the modern-day Junggar basin in northwest China because, as they confirmed, the region was located up in the arctic about 200 million years ago, and was covered in forests that regularly endured frigid winters. They found a sedimentary layer that also included lake ice-rafted debris with footprints of feathered herbivore dinosaurs. While their competitors dominated the balmy tropics, dinosaurs were quietly mastering life in Earth’s polar regions.

The End-Triassic Catastrophe Strikes

Then, disaster struck again. The Triassic–Jurassic (Tr-J) extinction event (TJME), often called the end-Triassic extinction, marks the boundary between the Triassic and Jurassic periods, 201.3 million years ago. It represents one of five major extinction events during the Phanerozoic, profoundly affecting life on land and in the oceans.

The end-Triassic extinction, global extinction event occurring at the end of the Triassic Period (252 million to 201 million years ago) resulted in the demise of some 76 percent of all marine and terrestrial species and about 20 percent of all taxonomic families. This extinction was different from its predecessor – instead of the slow-burning volcanic hell of the Siberian Traps, this catastrophe brought something worse: volcanic winter.

When Fire Brought Ice

As the Americas pulled away from Africa and Eurasia, magma erupted at the margins. The episode, now known as the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP), was one of the largest volcanic events in Earth’s history. But unlike typical volcanic warming, these eruptions had a chilling effect.

Widespread volcanic eruptions likely blocked out the sun roughly 202 million years ago for long periods. The resulting chill triggered a mass extinction event. Three-fourths of the planet’s species died off. These included many large reptiles. The massive eruptions spewed sulfur aerosols into the atmosphere, creating a planet-wide winter that could last for decades or even centuries.

The Great Dying of the Archosaurs

The volcanic winter was devastating for the dominant reptiles of the Triassic. On land, all archosauromorph reptiles other than crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, and pterosaurs became extinct. Crocodylomorphs, dinosaurs, pterosaurs, and mammals were left largely untouched, allowing them to become the dominant land animals for the next 135 million years.

Other animals, including crocodilians and their relatives, were dominant land animals in tropical and temperate regions but didn’t have insulation and therefore didn’t fare nearly as well. In fact, “they were almost completely wiped out” during the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event. But dinosaurs generally did just fine, and that’s why they became the dominant species on land during the Jurassic. The rulers of the warm Triassic world found themselves defenseless against the cold.

Feathered Survivors Inherit the Earth

While their naked competitors froze, dinosaurs thrived in the volcanic winter. But the secret to their survival may have been how well adapted they were to the cold, unlike other reptiles of the time. The dinosaurs’ warm coats of feathers could have helped the creatures weather relatively brief but intense bouts of volcanic winter associated with the massive eruptions.

“Dinosaurs were there during the Triassic under the radar all the time,” lead author Paul Olsen, a professor of biology and paleo environment at Columbia University’s Columbia Climate School said. “The key to their eventual dominance was very simple. They were fundamentally cold-adapted animals. When it got cold everywhere, they were ready, and other animals weren’t.” This adaptation gave them an enormous advantage when the world plunged into darkness and cold.

The Jurassic Takeover

At the end of the Triassic Period there was a mass extinction, the causes of which are still hotly debated. Many large land animals were wiped out but the dinosaurs survived, giving them the opportunity to evolve into a wide variety of forms and increase in number. As the volcanic winter ended and the world warmed again, dinosaurs found themselves the inheritors of a largely empty planet.

Dinosaurs might then have been able to spread rapidly during the Jurassic, occupying niches left vacant by less hardy reptiles. They didn’t just survive – they exploded into every conceivable ecological role. From tiny insectivores to massive plant-eaters, from swift predators to armored tanks, dinosaurs filled every available niche with remarkable speed and efficiency.

The Evolutionary Advantage of Being Prepared

Because organisms aren’t adapted for very rare global events, survival is more a matter of luck than some innate “superiority”. Dinosaurs survived the mass extinction at the end of the Triassic, but that doesn’t mean they were superior to the animals that went extinct or somehow “deserved” to succeed. However, their cold adaptations weren’t just luck – they were the result of millions of years of evolution in harsh polar environments.

Scientists argue that dinosaurs must already have been adapted to cold weather, perhaps even living in environments with seasonal winters, in advance of the Triassic extinction. Then, when the volcanic winters came, they were able to move south and deal with the colder temperatures. Their competitors, on the other hand, the uninsulated reptiles more closely related to crocodiles had already adapted to the warmest places on the planet, and when the world got colder, they had nowhere to go. They died out and the surviving dinosaurs were able to move into the niches they left behind.

Lessons from Deep Time

The dinosaur survival story offers profound insights into evolution and extinction. It has been suggested that feathers had originally functioned as thermal insulation, as it remains their function in the down feathers of infant birds prior to their eventual modification in birds into structures that support flight. What began as a simple adaptation to cold became the foundation for one of evolution’s most spectacular innovations – powered flight.

In the mid to late Triassic, the dinosaurs evolved from one group of archosaurs, and went on to dominate terrestrial ecosystems during the Jurassic and Cretaceous. This “Triassic Takeover” may have contributed to the evolution of mammals by forcing the surviving therapsids and their mammaliform successors to live as small, mainly nocturnal insectivores. The dinosaurs’ success reshaped the entire trajectory of life on Earth, pushing our own mammalian ancestors into the shadows for over 150 million years.

The story of dinosaur survival is ultimately a reminder that evolution doesn’t always favor the strongest or largest. Sometimes it rewards the most adaptable – those creatures humble enough to live in the margins, tough enough to endure the cold, and lucky enough to have the right tools when catastrophe strikes. Did you ever think that something as simple as staying warm would change the course of life on Earth forever?