Imagine discovering perfectly polished stones nestled inside the fossilized ribcage of a massive, ancient creature. Picture scientists puzzling over these mysterious rocks for over a century, debating whether they’re evidence of sophisticated digestion or just geological accidents. This isn’t science fiction – this is the fascinating world of gastroliths, the “stomach stones” that unlock secrets about how dinosaurs processed their meals millions of years ago.

What Are Gastroliths? The Stones That Tell Stories

Gastroliths get their name from ancient Greek words meaning “stomach” and “stone,” but these aren’t just any ordinary rocks. These are stones that have been in the digestive system of an animal, transformed by their journey through prehistoric guts into polished, rounded treasures that paleontologists prize today.

Some species retain gastroliths in their muscular gizzard and use them to grind food, while others simply swallow them temporarily. The process is surprisingly similar to what happens in a rock tumbler – constant friction and movement gradually smooths rough edges until jagged chunks become perfectly rounded pebbles.

The Great Stone Mystery: How Scientists First Discovered Gastroliths

The story begins in the early 1900s when puzzled paleontologists started finding something odd. In 1906, George Reber Wieland reported the presence of worn and polished quartz pebbles associated with the remains of plesiosaurs and sauropod dinosaurs, marking the first official recognition of these mysterious stones.

In 1907, Barnum Brown found gravel in close association with the fossil remains of the duck-billed hadrosaur Claosaurus and interpreted it as gastroliths. Brown was among the first paleontologists to recognize that dinosaurs used gastroliths in their digestive systems to aid in the grinding of food. However, not everyone was convinced by these early interpretations.

Modern Animals That Swallow Rocks: Nature’s Living Examples

Before we dive deeper into dinosaur digestion, it’s worth looking at creatures alive today that use this same strategy. Among living vertebrates, gastroliths are common among crocodiles, alligators, herbivorous birds, seals and sea lions. Your backyard chickens are actually following an ancient practice when they peck at gravel.

Stones swallowed by ostriches can reach lengths of up to 8-9 centimeters, with exceptional cases potentially exceeding this – that’s bigger than a golf ball! These modern examples help scientists understand how gastroliths might have functioned in prehistoric times, though the comparison isn’t always straightforward.

The Morrison Formation: A Treasure Trove of Ancient Stomach Stones

The American West’s Morrison Formation has become ground zero for gastrolith discoveries. Gastroliths have been found in the Morrison Formation, particularly in association with sauropod dinosaurs like Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus. These stones offer evidence of the digestive strategies used by these large herbivores to process fibrous plant material.

What makes these discoveries so remarkable is their context. Within the Morrison Formation, exotic pebble and cobble-size durable clasts of quartzite, chert and vein quartz weather out of the mudstone paleosols, and these exotic clasts are interpreted as gastroliths, carried within the gastric mills of dinosaurs. These weren’t just random rocks – they were carefully selected digestive aids.

Cedarosaurus: The Most Famous Gastrolith Discovery

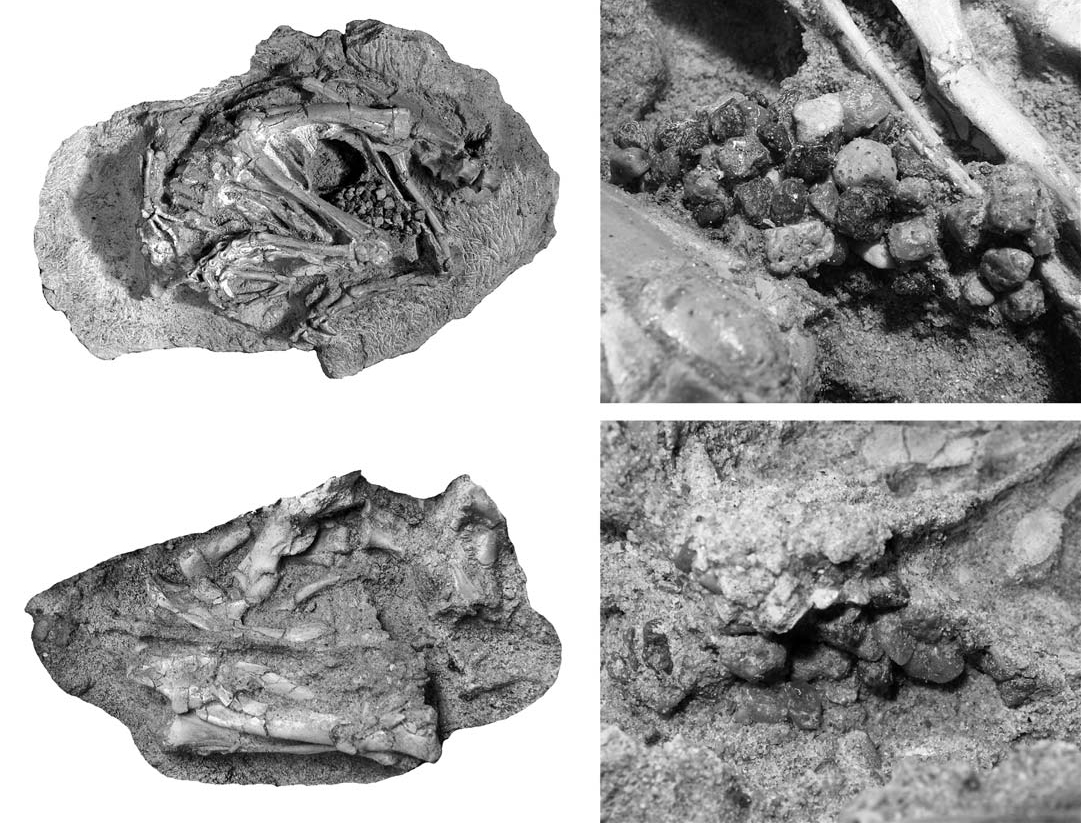

Perhaps no discovery has captured scientists’ imagination quite like the Cedarosaurus find. In 2001, Frank Sanders, Kim Manley, and Kenneth Carpenter published a study on 115 gastroliths discovered in association with a Cedarosaurus specimen. The stones were identified as gastroliths on the basis of their tight spatial distribution, partial matrix support, and an edge-on orientation indicative of their being deposited while the carcass still had soft tissue.

The numbers are staggering: nearly all of the Cedarosaurus gastroliths were found within a .06 cubic meter volume of space in the gut region of the skeleton. The total mass of the gastroliths themselves was 7 kilograms. That’s like finding 15 pounds of rocks concentrated in what would have been this dinosaur’s stomach!

The Detective Work: How Scientists Identify True Gastroliths

Not every smooth stone found near dinosaur bones gets the gastrolith label. Geologists usually require several pieces of evidence before they will accept that a rock was used by a dinosaur to aid its digestion. First, it should be rounded on all edges and some are polished because inside a dinosaur’s gizzard any genuine gastrolith would have been acted upon by other stones and fibrous materials in a process similar to the action of a rock tumbler.

Second, the stone must be unlike the rock found in its geological vicinity. Many gastroliths have been found in fine-grained lake, mud, and swamp deposits. When you find granite pebbles in a mudstone formation, you know something unusual happened – like a dinosaur carrying them there in its belly.

The Travel Bug: Dinosaurs as Ancient Stone Collectors

Some of the most mind-blowing gastrolith discoveries reveal dinosaurs as unexpected long-distance travelers. In early 2021, Joshua Malone and fellow researchers from the USA reported pink quartzite gastroliths from Wyoming that most likely came from the gut of a large sauropod such as Barosaurus or Diplodocus. When they crushed the stones to examine and get ages for the minerals inside, the closest geological match they could find was around 1000 kilometers to the east of the discovery site.

Malone and his team concluded that these huge dinosaurs may have carried the stones from at least that far away, as part of a long-distance migration. Picture these colossal creatures trekking across prehistoric landscapes, their stomachs filled with rocks picked up along the way – nature’s ultimate travel souvenirs!

The Great Debate: Did Sauropods Really Need These Stones?

Here’s where things get controversial. Recent research has thrown a wrench into our understanding of sauropod gastroliths. Based on feeding experiments with ostriches and comparative data for relative gastrolith mass in birds, sauropod gastroliths do not represent the remains of an avian-style gastric mill. Feeding experiments with farm ostriches showed that bird gastroliths experience fast abrasion in the gizzard and do not develop a polish.

The math is telling. Relative gastrolith mass in sauropods is much less than 0.1% of body mass, at least an order of magnitude less than that in ostriches and other herbivorous birds where gastrolith mass approximates 1% of body mass – suggesting these massive dinosaurs weren’t using stones the same way modern birds do.

Alternative Theories: Why Dinosaurs Might Have Swallowed Stones

If not for grinding food, then why did dinosaurs eat rocks? Scientists have proposed several intriguing alternatives. Possible alternatives include accidental or pathologic ingestion, or intentional ingestion for mineral uptake, especially calcium supply. While the calcium-rich limestone would have been quickly dissolved, acid-resistant rock types, such as quartz, could have remained in the stomach and may have accumulated as gastroliths, thereby developing polish through prolonged exposure to mild abrasion.

Another possibility involves buoyancy control. Aquatic animals, such as plesiosaurs, may have used gastroliths as ballast, to help balance themselves or to decrease their buoyancy, as crocodiles do. Though this theory faces its own challenges when scientists crunch the numbers on stone-to-body-weight ratios.

Beyond Dinosaurs: The Surprising Diversity of Ancient Stone Swallowers

Dinosaurs weren’t the only prehistoric creatures with a taste for rocks. In 2013, Laura Codorniú and her team published the first report of gastroliths in two pterosaurs (Pterodaustro guinazui). The stones were concentrated in the animal’s abdominal cavity and had likely been packaged inside a single organ, while the surrounding fine-grained claystone didn’t contain any similar pebbles.

Even more surprising, some gastroliths tell tales of the ancient food chain. Kenshu Shimada examined the remains of the Late Cretaceous shark Cretoxyrhina mantelli and found several polished black pebbles among the fossilized remains of one shark from Kansas. Since sharks don’t swallow stones, the most likely explanation was that this top predator had eaten something that did – giving us a fossil record of prehistoric predation.

The discovery reveals that gastroliths are a fundamental part of an animal’s digestion, for those that need them, and shouldn’t surprise us that they are also part of the wider circle of this-eats-that life. It’s a reminder that ancient ecosystems were just as interconnected as modern ones.

These mysterious stones continue to reshape our understanding of prehistoric life, proving that sometimes the smallest details – like a handful of polished pebbles – can unlock the biggest secrets about creatures that vanished 65 million years ago. What other secrets might be waiting in museum collections, disguised as ordinary rocks but holding extraordinary tales of ancient digestion and prehistoric behavior?