The world of paleontology is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle where most pieces are missing and you have no picture on the box to guide you. Scientists work with fragments of bone weathered by millions of years, trying to piece together creatures so alien that they challenge our understanding of life itself. Sometimes brilliant minds make spectacular mistakes.

These errors have shaped how we think about prehistoric life. Early paleontologists got those terrible lizards terribly : T. rex as a tail-dragging lunk, tank-like Iguanodon, long-necked sauropods submerged in water because surely they were too big to walk on land. One problem early paleontologists faced was that they were limited to merely looking at a fossil and finding a living animal to compare it with visually. Let’s dive into nine spectacular moments when some of history’s brightest scientists got it wonderfully, embarrassingly .

The Brontosaurus That Never Existed

To this day, the Brontosaurus remains one of the most popular and recognizable dinosaurs in history – an impressive feat for an animal that never existed. This mistake began during the heated “Bone Wars” of the late 1800s, when rival paleontologists Othniel Charles Marsh and Edward Drinker Cope raced to discover and name new species.

The confusion started in 1879, when collectors working in Wyoming for paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh found two nearly complete – yet headless – sauropod dinosaur skeletons. Wanting to display them, Marsh fitted one specimen with a skull found nearby, and the other with a skull he found in Colorado. Voila! – the Brontosaurus was born. It was simply a more complete Apatosaurus – one that Marsh, in his rush to one-up Cope, carelessly and quickly mistook for something new.

Iguanodon’s Misplaced Horn

Picture this: a massive rhinoceros-like beast with a horn jutting from its nose, lumbering through prehistoric forests on all fours. Unfortunately, that vision was terribly, terribly . Among the mistakes? The animal walked on all fours (it turned out to be a biped) and had a horn on its nose (the hornlike bone was actually a spiked thumb).

Some say Mary Ann Mantell discovered the first evidence of Iguanodon (some giant petrified teeth). Others believe it was her doctor husband, Gideon. Regardless, when Gideon presented the fossils, found in Sussex, to the Royal Society of London in 1822, the crowd was dumbfounded and assumed the teeth must belong to some as yet undiscovered huge fish, or possibly a rhinoceros. Scientists had no framework for understanding such creatures because the very concept of dinosaurs hadn’t been invented yet.

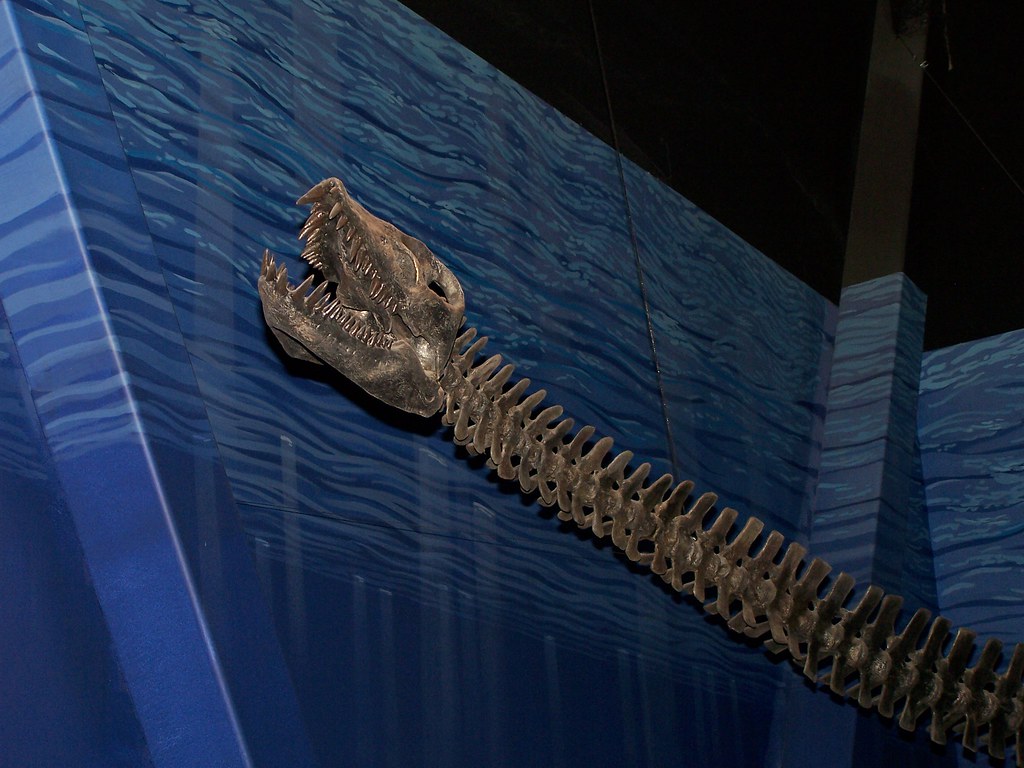

Elasmosaurus’s Backwards Head

In 1868, Edward Drinker Cope incorrectly restored the type specimen of Elasmosaurus platyurus, by placing the skull at the end of the animal’s tail. His error haunted him the rest of his career. Imagine trying to explain a giraffe-necked sea monster when nobody had ever seen anything like it before.

When Cope described Elasmosaurus in 1869, he placed its head at the end of its tail so that it looked like it had a short neck and a really long tail instead of the other way around. The bones were all jumbled together and the jaws had ended up at the end of the skeleton when it was covered over with sediment and the fossilization process began. Another paleontologist pointed out Cope’s mistake only a few months later. Cope’s nemesis Marsh got hold of a copy of the original article and was absolutely gleeful. He never would let Cope forget his mistake, and in fact it was the final straw in the relationship between the two.

The -Headed Apatosaurus

For decades, museums displayed their prized Apatosaurus skeletons with completely heads attached. For decades, Carnegie Museum of Natural History and other institutions displayed Apatosaurus with incorrect skulls. We now know that the long-displayed Apatosaurus was a construct, a figment of scientific imagination.

But the correct skull wasn’t identified and mounted until 1915 because paleontologist O.C. Marsh made another mistake a century earlier. When he published his reconstruction, no skull had ever been found attached to a body of the animal that we now call apatosaurus. So when Marsh went to publish a reconstruction of this animal in 1883, he used the head of another dinosaur to complete the skeleton. Visitors to major museums unknowingly admired chimeras – creatures cobbled together from different animals entirely.

Hypsilophodon the Tree-Climber

Swinton believed Hypsilophodon could climb with ease and probably lived in trees. Following recent studies of the dinosaur’s musculo-skeletal structure, this opinion is now universally regarded as incorrect. Hypsilophodon is now known to have used its two hind legs to run quickly on the ground.

This mistake persisted because scientists looked at the dinosaur’s grasping hands and assumed they worked like those of tree-dwelling animals they knew. The reality was far more dynamic – instead of a cautious tree-dweller, Hypsilophodon was a swift ground runner, perfectly adapted for life on open plains.

Sauropods as Aquatic Giants

Many scientists in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries considered sauropods to be much too large to fully support their weight on land and so showed them at least partially submerged in water. However, studies have since shown that their air-filled bones and small feet would not have been suited to a life in water.

Early paleontologists couldn’t imagine how such massive creatures could possibly support themselves on dry land. Parker shows Cetiosaurus as a semi-aquatic dinosaur. Although its long neck and tail are correctly drawn here, scientists now believe that, like other sauropods such as Diplodocus and Brachiosaurus, Cetiosaurus lived on land and held its tail in the air, rather than dragging it along the floor. These giants weren’t wallowing in ancient swamps – they were striding across continents.

Hallucigenia’s Upside-Down Life

One of these was Hallucigenia, so named because it looked like, well, a hallucination. It had at least seven pairs of rigid spikes on its back, seven pairs of weirdly floppy ‘legs’, and what appeared to be a large, bulbous head at one end. Many fossils were discovered without this head, which baffled scientists. Why were so many Hallucigenia getting decapitated?

The answer came during closer examination of what scientists thought was the butt end of the animal. It revealed teeth and eyes, leading researchers to a startling realization. They had misidentified the butt as the head. Scientists had literally been looking at this bizarre Cambrian creature completely backwards for years.

Tetrapodophis: The Non-Snake

Tetrapodophis amplectus, revealed in 2015, was a paleontological marvel. A fossil from 110 million years ago, the sinuous skeleton was, scientists said, something long-sought. The snake-like body had four tiny legs, marking the first discovery of the missing link between snakes and lizards. It was named accordingly and celebrated, but not everyone was convinced.

Earlier in 2021, a different team of paleontologists revealed the fruits of their long labor re-examining the remains: Tetrapodophis was no snake at all, but a member of an extinct genus of marine lizard called Dolichosaurus. The supposed missing link between snakes and lizards turned out to be neither snake nor evolutionary bridge.

Scleromochlus: The Misidentified Flying Reptile

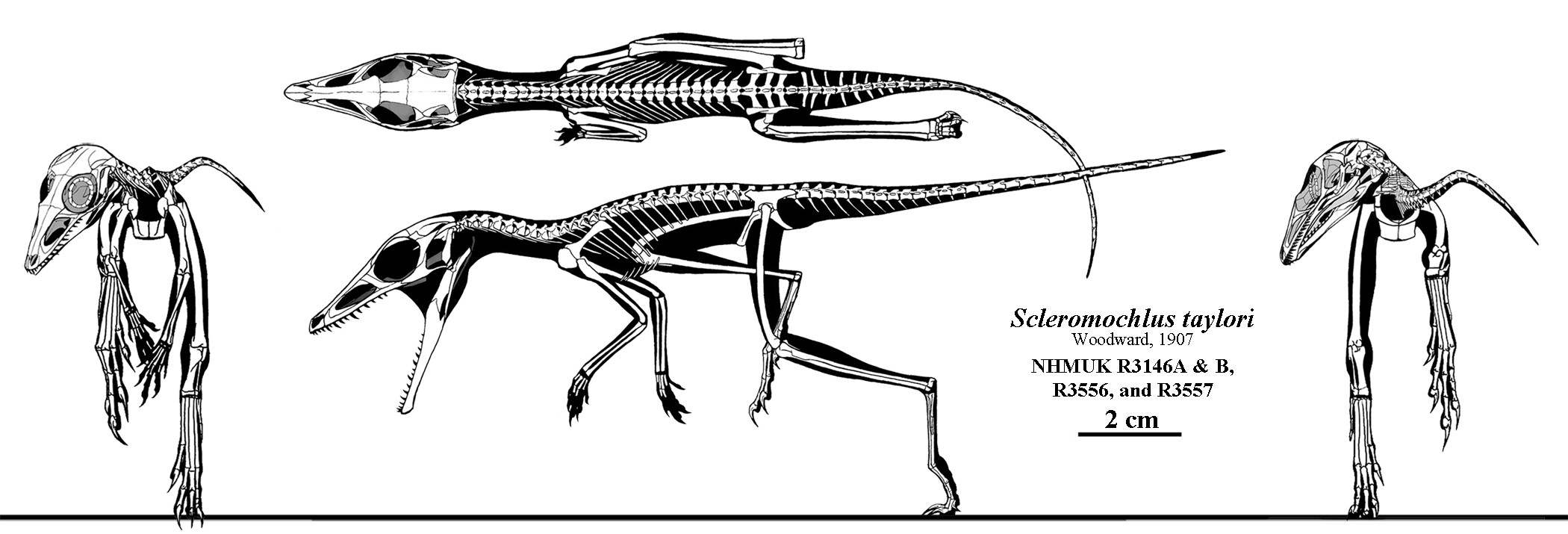

Parker based his creative reconstruction of Scleromochlus on a partial skeleton found in Scotland. At the time Swinton thought it was a theropod dinosaur, like Tyrannosaurus rex. However, although this extinct animal roamed the Earth 200 million years ago, Scleromochlus was not a dinosaur.

However, although this extinct animal roamed the Earth 200 million years ago, Scleromochlus was not a dinosaur. It is now thought to be closely related to the flying reptiles, pterosaurs. What seemed like an early dinosaur was actually something entirely different – a relative of creatures that would eventually take to the skies.

Conclusion

These spectacular mistakes remind us that science is a process of discovery, not a collection of unchanging facts. Lamanna is more cautious: “I’m sure we’re doing things now that we’ll regret one day, too.” Each error taught paleontologists something valuable about how to approach the next puzzle.

The most beautiful part? These mistakes didn’t diminish science – they made it stronger. Every turn led to better methods, more careful analysis, and deeper understanding. Today’s paleontologists use advanced scanning techniques, chemical analysis, and computer modeling that would amaze their predecessors.

What do you think the next generation of scientists will discover we got completely ? Share your thoughts in the comments.