In the late 19th century, American paleontology was forever transformed by one of the most bitter and destructive scientific rivalries in history. The “Bone Wars,” as they came to be known, pitted two brilliant but deeply flawed paleontologists against each other in a decades-long battle for scientific supremacy. Othniel Charles Marsh of Yale University and Edward Drinker Cope of the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia spent nearly 30 years locked in a ferocious competition, discovering hundreds of new dinosaur species while simultaneously attempting to destroy each other’s reputations, careers, and lives. Their rivalry drove unprecedented advancements in paleontology but came at tremendous personal and scientific cost. The story of the Bone Wars reveals how ambition, ego, and ruthlessness can both advance and impede scientific progress.

The Unlikely Scientific Combatants

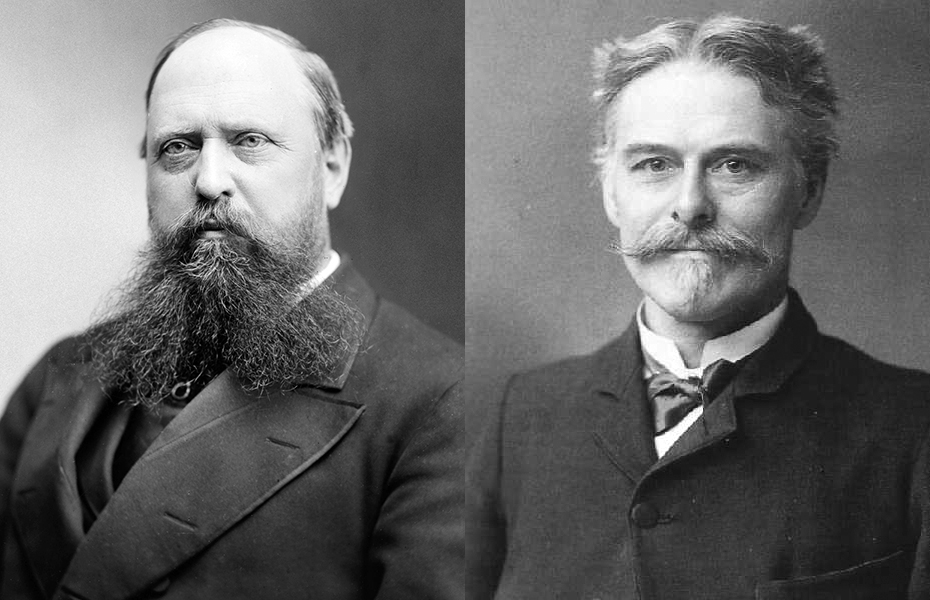

The two men at the center of the Bone Wars could hardly have been more different in personality and background. Othniel Charles Marsh, born to humble beginnings in 1831, was methodical, reserved, and detail-oriented. He leveraged his wealthy uncle George Peabody’s fortune to secure a position at Yale University and build the institution’s first paleontology program. Edward Drinker Cope, born into a wealthy Quaker family in 1840, was brilliant but impulsive, publishing his first scientific paper at age 18. Where Marsh was calculating and patient, Cope was passionate and quick to publish. Their contrasting approaches would later fuel their bitter rivalry, with Marsh meticulously collecting and studying specimens before publishing, while Cope rushed to print with his discoveries. These fundamental differences in scientific methodology and personality laid the groundwork for what would become a three-decade feud that transformed American paleontology.

The Initial Friendship

Before their legendary rivalry began, Marsh and Cope initially maintained a cordial professional relationship. They first met in Berlin in 1864 while both were studying in Europe to advance their knowledge of natural sciences. At this early stage, they exchanged letters and even named species after each other as a sign of mutual respect. Cope introduced Marsh to important fossil sites in New Jersey, sharing his knowledge generously with his colleague. Their early correspondence reveals two ambitious scientists united by their passion for paleontology at a time when the field was still in its infancy in America. This period of collegiality, however, would prove short-lived. The seeds of conflict were planted during these early interactions, as each man began to recognize the other as both a brilliant mind and a potential competitor in their quest for scientific recognition and prestige.

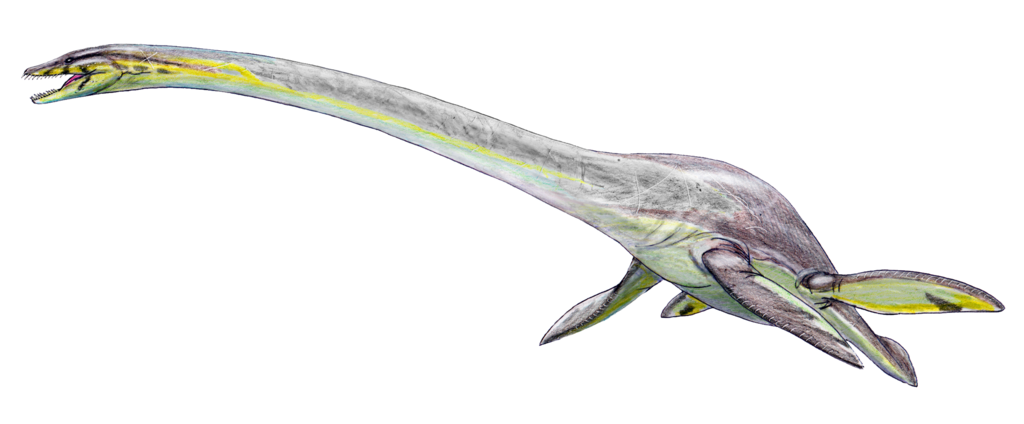

The Elasmosaurus Incident

The first major crack in their relationship appeared in 1868 with what became known as the “Elasmosaurus incident.” Cope had reconstructed and published a description of a plesiosaur fossil, Elasmosaurus platyurus, but made a critical error—he placed the skull on the end of the tail rather than the neck. When visiting Cope’s collection, Marsh noticed this mistake but initially said nothing directly to Cope. Instead, he pointed out the error to paleontologist Joseph Leidy, who publicly humiliated Cope by revealing the mistake. Cope was so mortified that he reportedly attempted to purchase and destroy all copies of the published journal containing his error. This public embarrassment deeply wounded Cope’s pride and marked the beginning of his animosity toward Marsh. The incident revealed both men’s true characters—Marsh’s willingness to undermine a colleague and Cope’s intense pride and sensitivity to criticism—setting the stage for their escalating conflict.

The Western Fossil Rush

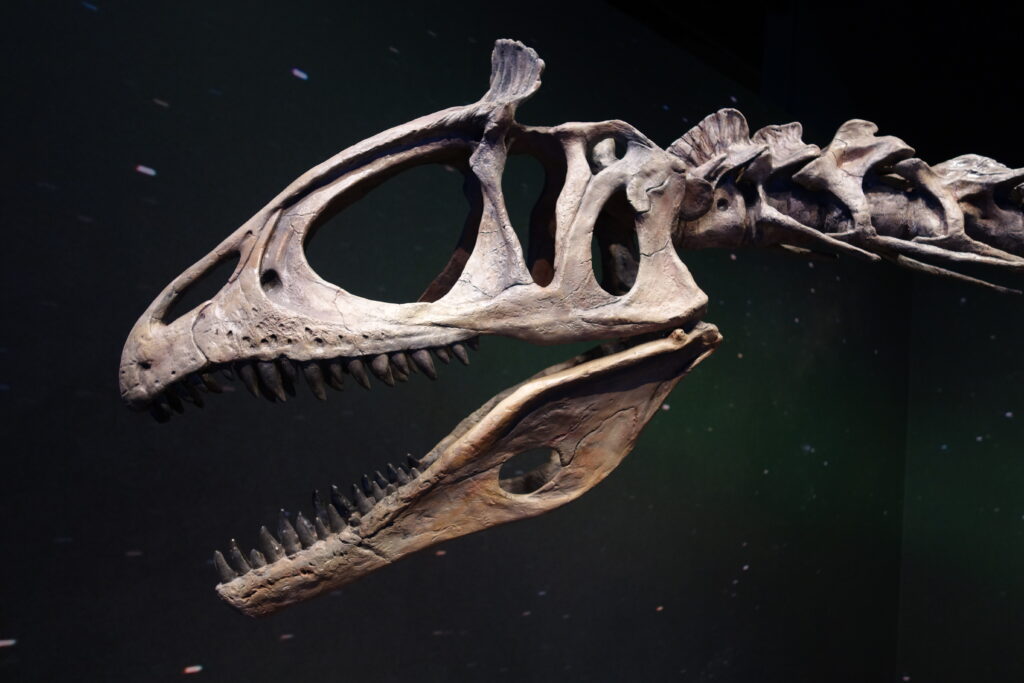

The rivalry truly ignited in 1877 when both men turned their attention to the fossil-rich beds of the American West. The completion of the transcontinental railroad had opened up vast new territories for fossil hunting, particularly in Colorado, Nebraska, Wyoming, and the Dakotas. What followed was essentially a paleontological gold rush, with both Marsh and Cope racing to claim the richest fossil sites and discover new species. Marsh, with greater financial resources from Yale and his uncle’s fortune, hired teams of collectors to scour the landscape and send specimens back east. Cope, working with more limited funds but incredible personal energy, often conducted fieldwork himself under harsh conditions. The western fossil beds proved extraordinarily productive, yielding remains of previously unknown dinosaurs that would revolutionize understanding of prehistoric life. This period saw the discovery of iconic dinosaurs like Stegosaurus, Allosaurus, Diplodocus, and Triceratops, many first described by either Marsh or Cope in their race for scientific priority.

Espionage and Sabotage Tactics

As the rivalry intensified, both men resorted to increasingly underhanded tactics to gain an advantage. Marsh, with his superior financial resources, bribed railroad workers to alert him to fossil discoveries and diverted shipments of Cope’s fossils to his facilities. He also paid Cope’s fossil hunters to secretly work for him instead, essentially creating a network of spies within his rival’s operation. Cope, meanwhile, rushed his findings into print, sometimes with hasty and error-filled descriptions, to claim priority over discoveries. Both men sent agents to infiltrate each other’s dig sites, with reports of workers destroying fossils they couldn’t take just to prevent their rival from claiming them. In one notorious incident, Marsh’s men allegedly dynamited a site after extracting the best specimens to ensure Cope would find nothing of value. These tactics moved well beyond scientific competition into the realm of personal vendetta and sabotage, with the advancement of knowledge becoming secondary to personal victory.

The Publication War

The battlefield of the Bone Wars extended beyond the fossil beds to scientific journals, where both men engaged in a frenzied publication race. The volume of their output was staggering—Cope published nearly 1,400 papers during his lifetime, while Marsh produced fewer but often more comprehensive works describing hundreds of new species. This rush to publish led to numerous errors, with both men naming the same species multiple times or creating species based on incomplete specimens that later proved invalid. They frequently criticized each other’s work in print, pointing out mistakes and questioning methodologies. Marsh, with his more deliberate approach, often accused Cope of carelessness, while Cope charged Marsh with deliberately delaying publication to incorporate others’ discoveries without credit. Their publication battle became so heated that some journals became reluctant to publish their increasingly vitriolic papers, concerned about the damage to scientific discourse. This aspect of their rivalry tragically undermined the scientific value of much of their work, creating a taxonomic tangle that later paleontologists would spend decades sorting out.

Financial and Personal Ruin

The obsessive nature of the rivalry eventually led to devastating personal consequences for both men. Cope, who had inherited considerable wealth, gradually spent his entire fortune funding expeditions and publications to outdo Marsh. By the 1880s, he was forced to sell much of his fossil collection and eventually his family home to continue his work, living in reduced circumstances in his later years. Marsh, while financially secure through his Yale position and family connections, became increasingly isolated and paranoid, alienating colleagues with his secretive and controlling behavior. Both men sacrificed personal relationships and health in pursuit of their feud. Cope’s marriage suffered irreparable damage, while Marsh never married, devoting himself entirely to his work and the rivalry. The all-consuming nature of their conflict transformed what should have been triumphant careers into cautionary tales about the destructive power of unchecked ambition and personal animosity.

The Media Spectacle

By the 1890s, the Bone Wars had escaped the confines of academic circles to become a public spectacle. The New York Herald published a series of interviews with Cope in 1890 in which he openly attacked Marsh’s character and scientific integrity. Eager for a sensational story, newspapers across the country picked up on the feud, portraying the two scientists as bitter enemies locked in a fierce battle for dinosaur supremacy. The public was fascinated by tales of fossil theft, espionage, and academic backstabbing set against the romantic backdrop of the American frontier. This media attention brought paleontology into the public consciousness like never before, creating widespread interest in dinosaurs and prehistoric life. Ironically, while their conflict damaged their scientific legacy, the publicity it generated helped establish American paleontology as a field of significant public interest and importance, laying the groundwork for the popular fascination with dinosaurs that continues today.

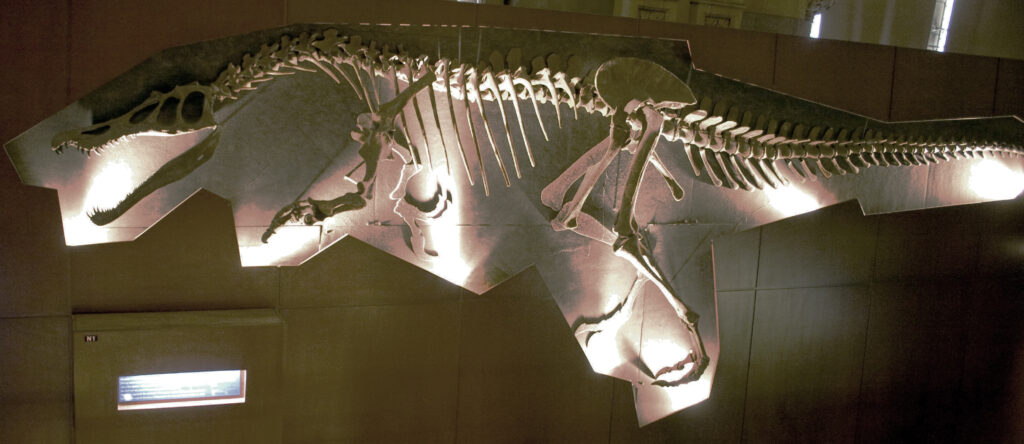

Scientific Impact and Discoveries

Despite the destructive nature of their rivalry, the scientific output of the Bone Wars was undeniably impressive. Together, Marsh and Cope discovered and named more than 136 new species of dinosaurs, effectively creating the foundation of North American paleontology. Marsh’s discoveries included iconic dinosaurs such as Triceratops, Stegosaurus, Apatosaurus (which he incorrectly named Brontosaurus), and Allosaurus. Cope described important finds including Dimetrodon, Camarasaurus, and Coelophysis. Beyond dinosaurs, they identified countless other prehistoric creatures, including mammals, fish, and reptiles, greatly expanding scientific understanding of ancient life. Their work helped establish evolutionary patterns and relationships between species that supported Darwin’s then-controversial theory of evolution. The sheer volume of fossil material they collected created invaluable museum collections that continue to serve researchers today. Despite their failings and the questionable methods they sometimes employed, their collective contributions revolutionized paleontology and fundamentally changed how we understand prehistoric life on Earth.

The Taxonomic Legacy and Cleanup

The hasty nature of many publications during the Bone Wars created a taxonomic nightmare that took generations of paleontologists to resolve. In their rush to claim priority, both men frequently named species based on fragmentary remains, sometimes creating multiple names for the same animal or combining bones from different species into fictional creatures. Cope was particularly guilty of rushing descriptions into print with insufficient evidence. After their deaths, paleontologists spent decades sorting through their collections, correcting errors, and resolving the confusing tangle of names they left behind. Notable examples include Marsh’s Brontosaurus, which was later determined to be the same as the previously described Apatosaurus (though recent research has suggested they may be distinct genera after all). The cleanup process continued well into the 20th century, with some taxonomic issues stemming from the Bone Wars remaining unresolved even today. This messy legacy serves as a cautionary tale about the dangers of prioritizing speed and competition over careful, collaborative scientific methods.

The Bitter End

The rivalry continued unabated until Cope died in 1897, by which time both men were shadows of their former selves. Cope, financially ruined and in poor health, made a final peculiar competitive gesture by donating his body to science, challenging Marsh to do the same so that their brain sizes could be compared—a last attempt to prove his intellectual superiority. Marsh, however, declined this final contest and was buried conventionally when he died two years later in 1899. In his final years, Cope lived in a small apartment surrounded by fossil specimens, working until nearly his last day despite deteriorating health. Marsh, though financially secure, became increasingly isolated at Yale, his reputation damaged by Cope’s public attacks and his difficult personality. Neither man ever expressed regret for the excesses of their rivalry or reconciled before death. Their lives ended much as they had been lived—in competition, bitterness, and an unquenchable passion for paleontology that ultimately consumed them both.

Modern Assessment and Ethical Reflections

From a modern scientific perspective, the methods and ethics of the Bone Wars represent a cautionary tale about how not to conduct research. Contemporary paleontologists emphasize careful excavation, precise documentation, collaboration, and peer review—practices often ignored during the heated rivalry. Modern excavations focus on preserving contextual information about fossils that Marsh and Cope frequently disregarded in their haste. The scientific community now recognizes that their approach, while productive in terms of raw discoveries, damaged the scientific value of many specimens and created long-lasting confusion. Their rivalry also established problematic precedents in paleontology, including the rush to name new species and the privatization of fossil resources that continues to challenge the field today. Despite these criticisms, there’s recognition that their work occurred in a different era with different standards, and that their passion, however misdirected, laid crucial groundwork for modern paleontology. Their legacy reminds scientists of the importance of balancing competitive drive with ethical responsibility and collaborative spirit.

Popular Culture and Lasting Legacy

The dramatic story of the Bone Wars has captured public imagination for generations, inspiring books, documentaries, museum exhibits, and even fictional portrayals. The 2018 film “The Dinosaur Hunters” dramatized their rivalry, while numerous popular science books have recounted the tale for general audiences. Museums housing collections from both men, including the Yale Peabody Museum and the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, continue to highlight their contributions alongside the more problematic aspects of their methods. The rivalry has become a staple case study in the history of science, illustrating how personal ambition can both drive and distort scientific progress. Perhaps most importantly, the Bone Wars created a lasting public fascination with dinosaurs and fostered an American tradition of paleontology that continues to this day. The dramatic nature of their conflict brought paleontology into public consciousness in ways that more measured scientific work might never have achieved, helping to ensure ongoing public support for and interest in the field of paleontology more than a century after their deaths.

The Lasting Legacy and Lessons of the Bone Wars

The story of the Bone Wars represents one of science’s great paradoxes—a rivalry so destructive it nearly ruined both participants while simultaneously advancing their field in unprecedented ways. Marsh and Cope’s legacy is deeply ambivalent, combining remarkable scientific achievements with cautionary lessons about ego, ethics, and the human elements that shape scientific progress. Their discoveries forever changed our understanding of Earth’s prehistoric past, populating museums worldwide and igniting public fascination with dinosaurs that endures to this day. Yet their methods and the personal costs of their rivalry remind us that science at its best is a collaborative, careful enterprise, not a battlefield for personal vendettas. As we continue to benefit from their discoveries while working to correct their errors, the Bone Wars stand as a complex chapter in scientific history—one that reveals both the heights of human curiosity and the depths of human failing.