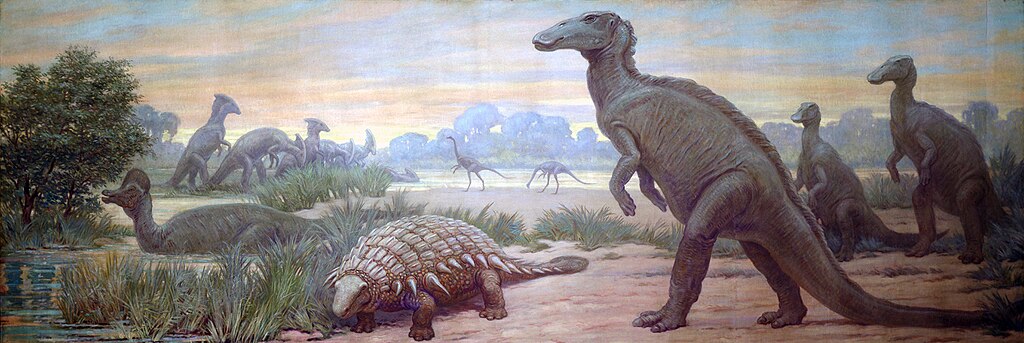

In the shadows of the mighty dinosaurs lived a remarkable creature that has only recently begun to reveal its secrets to paleontologists. Meet Repenomamus, a badger-sized mammal that roamed the forests of what is now northeastern China during the Early Cretaceous period, approximately 125 million years ago. Unlike the stereotype of early mammals as tiny shrew-like creatures scurrying beneath the feet of dinosaurs, Repenomamus boldly challenged the dinosaur-dominated food chain. These hyena-like mammals not only survived alongside dinosaurs but occasionally feasted on them, turning the tables on what we once thought about mammal-dinosaur relationships in the Mesozoic era.

The Discovery That Shocked Paleontologists

The scientific world was stunned in 2005 when researchers announced the discovery of a Repenomamus specimen with the remains of a young dinosaur in its stomach. This groundbreaking fossil, unearthed from the Yixian Formation in Liaoning Province, China, provided direct evidence that some mammals actually ate dinosaurs—a concept that contradicted the long-held belief that early mammals were exclusively insectivores. The specimen contained the unmistakable remains of a juvenile psittacosaur, a small beaked dinosaur common in the region. The dinosaur bones were fragmented but identifiable, with clear bite marks indicating that the Repenomamus had consumed its dinosaurian meal shortly before its own death. This single fossil dramatically changed our understanding of Mesozoic food webs and the ecological role of early mammals.

Repenomamus: An Introduction to the Dinosaur Eater

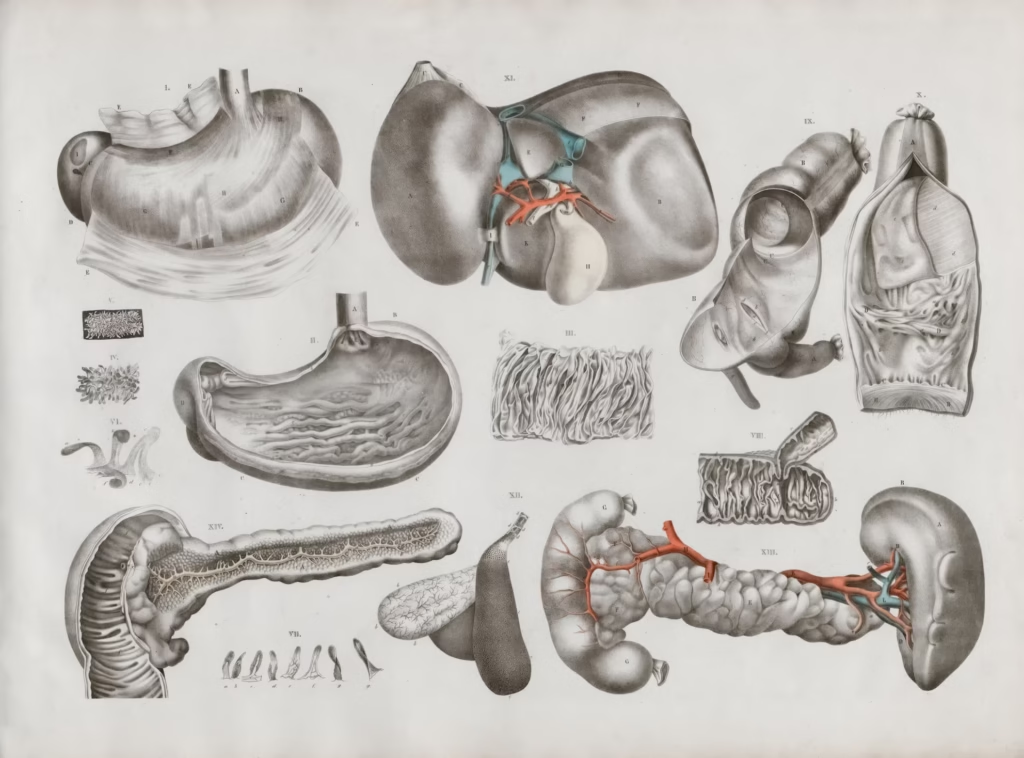

Repenomamus is represented by two known species: Repenomamus giganticus and the slightly smaller Repenomamus robustus. R. giganticus was truly exceptional for its time, reaching sizes of up to 1 meter (3.3 feet) in length and weighing an estimated 12-14 kilograms (26-31 pounds)—dimensions more akin to a modern badger or small dog than the mouse-sized mammals typically associated with the dinosaur era. Its robust skeleton suggests a powerful, muscular build adapted for strength rather than speed. The skull of Repenomamus was large and broad, housing impressive jaws lined with sharp teeth suited for a carnivorous lifestyle. Unlike many contemporary mammals, Repenomamus walked with a more upright gait, with limbs positioned under the body rather than splayed to the sides, allowing it to move efficiently through its Cretaceous habitat.

The Evolutionary Position of Repenomamus

Repenomamus belongs to an extinct group of mammals called triconodonts, which were part of the mammalian lineage but diverged before the emergence of marsupials and placentals. These animals are considered primitive mammals that retained several ancestral features while developing specialized adaptations for their ecological niche. The triconodonts were characterized by their distinctive three-cusped molar teeth arranged in a straight line, an arrangement different from most modern mammals. Repenomamus represents one of the largest and most specialized members of this group, demonstrating that early mammalian evolution included various experiments with size and ecological roles. Its existence challenges the simplified narrative that mammals remained small and unspecialized until after the dinosaur extinction, showing that diverse mammalian body plans and lifestyles emerged much earlier than previously thought.

The Cretaceous Environment: Setting the Stage

During the Early Cretaceous when Repenomamus prowled the landscape, northeastern China was a temperate region dominated by coniferous forests, lakes, and wetlands. The climate was seasonal, with distinct warm and cool periods throughout the year. This environment supported a rich diversity of life, including various dinosaur species like Psittacosaurus, the feathered dinosaur Microraptor, primitive birds, pterosaurs, and a variety of other mammals. Volcanic activity was common in the region, periodically blanketing the area in ash—a destructive force for living creatures but a boon for fossilization. These conditions created the perfect scenario for preserving delicate specimens in remarkable detail, including soft tissues, feathers, fur, and even stomach contents. The exceptional preservation of fossils from this time and place, known as the Jehol Biota, has provided paleontologists with an unprecedented window into this ancient ecosystem.

Hunting Habits and Dietary Preferences

The anatomy of Repenomamus reveals much about its carnivorous lifestyle and hunting strategies. Its powerful jaw muscles, sharp teeth, and robust limbs suggest it was an active predator capable of subduing small prey and tearing flesh. Unlike insectivorous mammals that focus on catching and crushing tiny invertebrates, Repenomamus had the dental and skeletal equipment necessary for processing larger prey, including small vertebrates. Evidence indicates it may have been an opportunistic predator, hunting animals it could overpower while also scavenging larger carcasses when available. The famous specimen containing dinosaur remains could represent either a successful hunt of a juvenile dinosaur or opportunistic scavenging—the debate continues among paleontologists. Whatever the case, Repenomamus had a varied diet that placed it higher in the food web than most of its mammalian contemporaries, allowing it to exploit resources unavailable to smaller, insect-eating mammals.

Comparing Repenomamus to Modern Predators

In many ways, Repenomamus occupied an ecological niche similar to today’s medium-sized carnivores like foxes, badgers, and small wild cats. Its body proportions and estimated capabilities suggest a lifestyle perhaps most comparable to that of the Tasmanian devil—an opportunistic predator and scavenger with powerful jaws and a stocky build. Like modern mesopredators, Repenomamus likely played an important role in its ecosystem by controlling populations of smaller animals while itself serving as potential prey for larger predators. The comparison to hyenas is particularly apt when considering its likely scavenging behavior and powerful jaw apparatus, though Repenomamus was considerably smaller than modern hyenas. Understanding these ecological parallels helps paleontologists reconstruct the complex web of interactions that characterized Mesozoic ecosystems, moving beyond the simplified view of dinosaurs as the only significant players in these ancient food webs.

Locomotion and Daily Life

The postcranial skeleton of Repenomamus provides important clues about how this animal moved through its environment. Unlike many early mammals that were primarily arboreal (tree-dwelling), Repenomamus appears to have been predominantly terrestrial, spending most of its time on the ground. Its limbs were relatively short but powerful, with feet adapted for walking and digging rather than climbing or swimming. Paleontologists believe it may have been capable of short bursts of speed when hunting or evading predators, but was not built for sustained running. The animal likely had a home range or territory that it patrolled regularly in search of food. With its powerful forelimbs and claws, Repenomamus may have been capable of digging simple burrows or modifying existing cavities for shelter, though no direct evidence of such behavior has been preserved. Its daily activities probably centered around finding food, avoiding larger predators, and potentially defending territory from competitors.

Reproduction and Life History

Details about the reproductive biology of Repenomamus remain speculative, as direct evidence of its reproductive habits has not been discovered. However, based on what we know about related mammals and its evolutionary position, paleontologists can make educated guesses about its life history. As a triconodont, Repenomamus likely reproduced by laying eggs, similar to modern monotremes like the platypus, rather than giving live birth like marsupials and placental mammals. Young Repenomamus would have been relatively undeveloped at hatching, requiring extended parental care until they were capable of independent survival. Growth was probably relatively rapid compared to modern mammals of similar size, with individuals potentially reaching sexual maturity within a year or two. The lifespan of Repenomamus in the wild was likely short by modern mammalian standards—perhaps 5-8 years—due to the harsh realities of living alongside predatory dinosaurs and other threats in the Cretaceous ecosystem.

Repenomamus in the Context of Mammalian Evolution

The existence of Repenomamus forces us to reconsider traditional narratives about mammalian evolution during the Mesozoic Era. Far from being an age where mammals were uniformly small, nocturnal, and ecologically constrained, the discovery of this badger-sized predator demonstrates that mammals had already begun exploring diverse body sizes and ecological roles while dinosaurs still dominated the landscape. This evolutionary experimentation was happening at least 60 million years before the extinction event that would eventually clear the way for mammalian dominance. Repenomamus represents an early, independent attempt at filling a medium-sized predator niche—a trial run, so to speak, for the mammalian predators that would proliferate after the dinosaurs’ disappearance. While this particular evolutionary lineage ultimately ended without leaving direct descendants, it demonstrates that the capability for mammals to evolve larger body sizes and more specialized predatory adaptations was present long before the end of the Cretaceous period.

The Significance of Stomach Contents in Paleontology

The discovery of dinosaur remains in the stomach of Repenomamus represents one of the most important examples of preserved stomach contents in the fossil record. Such direct evidence of feeding behavior is exceedingly rare and provides invaluable insights into ancient food webs that cannot be obtained through other means. While tooth marks on bones and coprolites (fossilized feces) can provide indirect evidence of predator-prey relationships, preserved stomach contents offer unambiguous proof of what an animal actually consumed shortly before death. The Repenomamus specimen contained numerous bones from a juvenile Psittacosaurus, including limb fragments and ribs, arranged in a way that clearly indicated they were inside the mammal’s digestive tract. The bones show signs of being broken down by stomach acids but were not fully digested, suggesting the mammal died relatively soon after its meal. This remarkable preservation was possible because of the rapid burial and exceptional fossilization conditions of the Yixian Formation, where volcanic ash often entombed animals quickly after death, preventing decomposition and scavenging.

Challenging Scientific Assumptions

The discovery of Repenomamus and its dinosaur-eating habits forced paleontologists to reassess long-held assumptions about Mesozoic ecosystems. Prior to this finding, the prevailing view was that mammals during the “Age of Dinosaurs” were strictly small, nocturnal creatures that posed no threat to even the smallest dinosaurs. Mammals were generally characterized as occupying marginal ecological niches, feeding primarily on insects and occasionally small vertebrates like lizards or amphibians. Repenomamus dramatically challenged this paradigm by demonstrating that some mammals were large enough and powerful enough to prey on dinosaurs, albeit young ones. This discovery exemplifies how single, well-preserved fossils can overturn decades of scientific consensus and open new avenues for research. The reassessment of mammal-dinosaur interactions has led paleontologists to look more closely at other Mesozoic mammals, revealing a greater diversity of sizes, diets, and ecological roles than previously appreciated, and painting a more complex picture of life during this fascinating period of Earth’s history.

Extinction and Legacy

Despite its impressive adaptations, Repenomamus and its relatives eventually disappeared from the fossil record, leaving no direct descendants among modern mammals. The extinction of these triconodonts occurred well before the end-Cretaceous mass extinction that claimed the non-avian dinosaurs, suggesting their disappearance was not related to that catastrophic event. Instead, they may have been outcompeted by other emerging mammal groups with more efficient anatomies or reproductive strategies. Though Repenomamus itself vanished, its ecological niche—that of a medium-sized opportunistic predator—would be filled repeatedly throughout mammalian evolution by various lineages. The legacy of Repenomamus lives on in our enhanced understanding of Mesozoic ecosystems and early mammalian capabilities. Its discovery fundamentally altered how scientists view the relationship between mammals and dinosaurs, creating a more nuanced appreciation for the complex ecological interactions that characterized life during the Cretaceous period. In many ways, Repenomamus foreshadowed the ecological diversification that mammals would undergo after the dinosaur extinction, showcasing the evolutionary potential that was waiting in the wings.

Future Research Directions

The study of Repenomamus continues to evolve as new specimens are discovered and existing fossils are reexamined with cutting-edge technologies. Paleontologists are particularly interested in finding more specimens with preserved stomach contents to further elucidate the dietary habits of this unusual mammal. Advanced imaging techniques like micro-CT scanning are being employed to examine the internal anatomy of Repenomamus fossils in unprecedented detail, revealing aspects of brain structure, inner ear morphology, and other soft tissue features that provide insights into sensory capabilities and behavior. Stable isotope analyses of teeth and bones may offer clues about the animal’s diet and habitat preferences. Additionally, researchers are searching for evidence of other large mammals that might have coexisted with Repenomamus, potentially revealing a greater diversity of sizeable Mesozoic mammals than currently recognized. The continued investigation of the Jehol Biota more broadly promises to yield further surprises about the ecological relationships between early mammals and their dinosaurian contemporaries, perhaps uncovering additional examples of mammals that defied conventional expectations about their place in Mesozoic food webs.

Conclusion

The story of Repenomamus represents a fascinating chapter in the history of life on Earth—one that rewrites our understanding of the relationship between mammals and dinosaurs during the Mesozoic Era. This badger-sized mammal, with its powerful jaws and predatory lifestyle, demonstrates that the ecological roles of early mammals were more diverse and significant than previously thought. While dinosaurs undoubtedly dominated the terrestrial ecosystems of the Cretaceous, mammals like Repenomamus were not merely living in their shadows but were active participants in the complex food web, occasionally even turning the tables on smaller dinosaurs. As paleontologists continue to unearth and analyze fossils from this distant era, our picture of life during the Age of Dinosaurs becomes increasingly nuanced, revealing a world where the seeds of mammalian diversity and ecological significance were already being sown, long before mammals would inherit the Earth.