In the vast plains of prehistoric Mongolia, roamed one of the most enigmatic and fearsome predators of the Eocene epoch – Andrewsarchus. Often described as wolf-like despite being much larger than any wolf that ever lived, this mysterious mammal has fascinated paleontologists since its discovery nearly a century ago. With limited fossil evidence but abundant scientific speculation, Andrewsarchus represents one of paleontology’s most intriguing puzzles. This massive carnivore, possibly the largest land-dwelling meat-eating mammal that ever lived, occupied a world vastly different from our own, approximately 45-36 million years ago. Let’s explore what we know about this remarkable prehistoric beast, its characteristics, habitat, and the ongoing scientific debate about its true nature.

Discovery and Naming: Unearthing a Prehistoric Giant

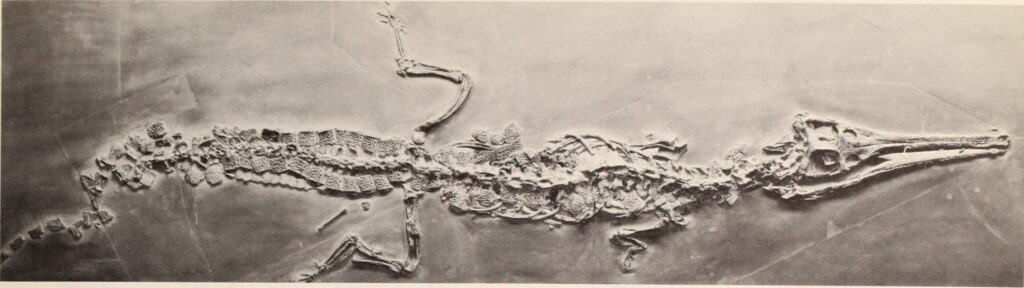

The story of Andrewsarchus begins in 1923 during the famous Central Asiatic Expeditions led by the American Museum of Natural History. During this groundbreaking paleontological venture into the Gobi Desert of Mongolia, expedition member Kan Chuen Pao discovered a massive skull measuring nearly three feet long. This remarkable find was named Andrewsarchus mongoliensis in honor of Roy Chapman Andrews, the expedition leader who would later become the director of the American Museum of Natural History. Interestingly, despite its significance, this single skull remains the only definitive fossil of Andrewsarchus ever discovered, making it one of the most poorly known yet frequently discussed prehistoric mammals in paleontological circles. The lack of additional skeletal material has forced scientists to make educated guesses about its appearance and lifestyle based on comparable creatures and anatomical analysis of the skull alone.

Physical Appearance: Reconstructing a Beast from a Single Skull

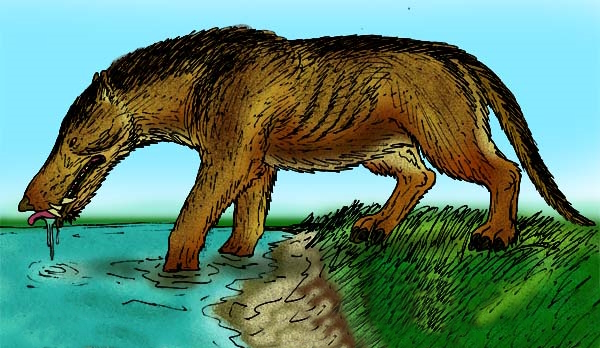

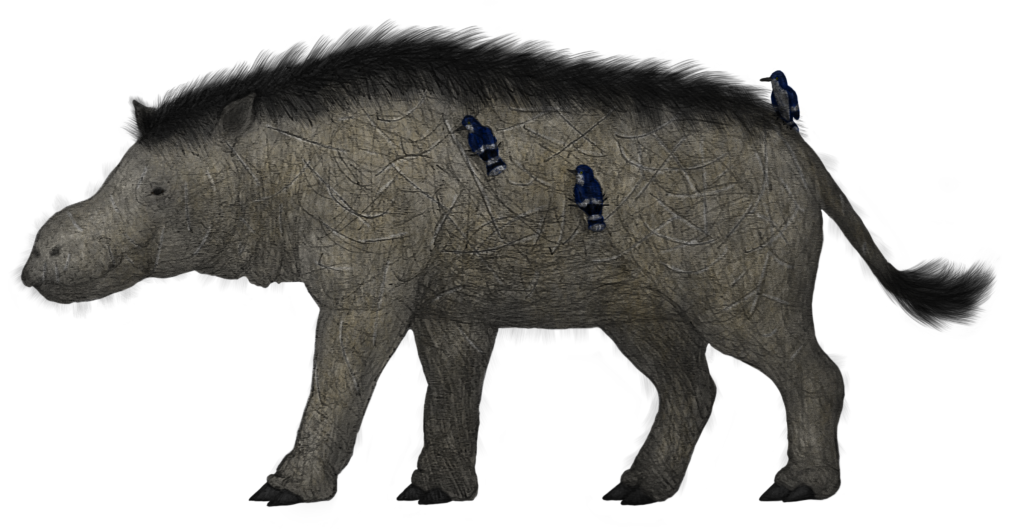

Reconstructing the complete appearance of Andrewsarchus presents a significant challenge for paleontologists, given the limited fossil evidence. Based on the massive skull (approximately 83 cm or 33 inches long), scientists estimate that Andrewsarchus likely measured between 3.5 and 4.5 meters (11-15 feet) from nose to tail and stood approximately 1.8 meters (6 feet) tall at the shoulder. Weight estimates range dramatically from 250 to over 1,000 kilograms (550-2,200 pounds), reflecting the uncertainty in its overall body proportions. Most reconstructions depict Andrewsarchus with a somewhat wolf-like body, powerful limbs, and a long tail, though these details remain speculative. The creature likely had a large head relative to its body, with powerful jaw muscles anchored to the prominent sagittal crest visible on the skull. Its coat and coloration remain entirely unknown, though many artistic representations show it with a shaggy, wolf-like or bear-like coat suitable for the variable climate of its time.

Taxonomic Classification: Finding Its Place in the Mammalian Family Tree

The taxonomic classification of Andrewsarchus has been subject to considerable debate and revision over the decades since its discovery. Initially, Andrewsarchus was classified among the mesonychids, an extinct group of hoofed predators that were once thought to be closely related to whales. However, more recent analysis has suggested alternative classifications. Some researchers now place Andrewsarchus among the artiodactyls (even-toed ungulates), making it more closely related to modern hippopotamuses, pigs, and cetaceans (whales and dolphins) than to wolves or other carnivores. This reclassification is based on subtle features of the skull and teeth that align more closely with artiodactyl anatomy than with true carnivores. The ongoing uncertainty about its classification highlights the challenges in paleontology when working with limited fossil evidence and demonstrates how our understanding of prehistoric life continues to evolve with new analytical techniques and discoveries.

Fearsome Dentition: The Teeth of a Specialized Feeder

The dentition of Andrewsarchus provides crucial clues about its dietary habits and evolutionary relationships. Its impressive dental array included large, pointed canines suitable for seizing prey or tearing flesh, combined with broad, crushing premolars and molars that could process tough materials. Unlike true carnivores, which have specialized shearing teeth (carnassials), Andrewsarchus possessed more generalized teeth, suggesting an omnivorous or durophagous (shell-crushing) diet. The wear patterns on its teeth indicate that Andrewsarchus may have used its powerful jaws to crush hard materials such as bones, shells, or tough plant matter. Each tooth was firmly anchored in powerful jaws that could exert tremendous bite force, estimated to be among the strongest of any mammalian predator. This combination of piercing and crushing teeth made Andrewsarchus a versatile feeder that could exploit various food sources in its environment, potentially giving it an advantage in the competitive ecosystems of Eocene Mongolia.

Habitat and Environment: The Mongolian Landscape of the Eocene

During the Eocene epoch, when Andrewsarchus roamed, Mongolia presented a dramatically different environment from today’s arid landscape. The region experienced a much warmer and more humid climate, with expansive forests and woodlands interspersed with open grasslands. Rivers and floodplains created diverse habitats supporting a rich variety of life. Paleoenvironmental studies indicate that Andrewsarchus inhabited coastal environments along an ancient body of water known as the Tethys Sea, which once covered parts of what is now central Asia. The fossil-bearing formation where Andrewsarchus was discovered, the Irdin Manha Formation, contains sediments consistent with floodplains and estuarine environments. This coastal habitat would have provided diverse hunting and scavenging opportunities, including marine animals that may have washed ashore or semi-aquatic creatures inhabiting the shoreline. The combination of terrestrial and marine food sources in this environment aligns with theories about Andrewsarchus’s omnivorous dietary adaptations.

Feeding Behavior: Predator, Scavenger, or Omnivore?

The feeding behavior of Andrewsarchus remains a subject of scientific debate, with several competing theories based on its unusual dental and cranial anatomy. Some paleontologists propose that Andrewsarchus was primarily a scavenger, using its powerful jaws to crack open bones and extract nutritious marrow after other predators had finished with their kills. Others suggest it may have been an active predator capable of bringing down large prey with its strong bite and robust build. A third possibility, gaining increasing support, is that Andrewsarchus was an omnivorous shore-dweller that fed opportunistically on beached marine animals, shellfish, turtles, and various plant materials. The structure of its teeth, particularly the broad molars capable of crushing hard materials, supports this theory of dietary flexibility. Comparative studies with modern animals like hyenas and certain bears, which combine predatory and scavenging behaviors with omnivorous tendencies, may provide the best analogs for understanding Andrewsarchus’s feeding ecology.

Size Comparison: How Andrewsarchus Measured Up to Other Predators

Andrewsarchus stands as potentially the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammal ever known, though this claim depends on both its exact size and how strictly “carnivorous” ly was. If the upper size estimates are accurate, Andrewsarchus would have dwarfed modern predators like tigers and polar bears, which typically weigh between 300-700 kg (660-1,540 pounds). It would have been comparable in size to some of the smaller species of Tyrannosaurus that lived millions of years earlier, though with a completely different body plan and ecological niche. Among its contemporaries, Andrewsarchus would have been significantly larger than other predatory mammals of the Eocene, including creodonts and early carnivores. Its closest competitors in size may have been certain species of entelodonts (sometimes called “hell pigs”), which were similarly built omnivorous mammals that could exceed 1,000 kg (2,200 pounds). This exceptional size would have made Andrewsarchus virtually immune to predation as an adult and capable of dominating feeding sites when competing with other carnivores.

Locomotion and Movement: How Did This Giant Travel?

Without post-cranial skeletal remains, reconstructing the locomotion of Andrewsarchus involves considerable speculation based on related animals and biomechanical principles. Most paleontologists believe Andrewsarchus was primarily terrestrial and likely moved with a characteristically mammalian gait, probably similar to bears or large ungulates rather than wolf-like canids. Its feet may have featured hooves or hoof-like structures rather than paws with claws, based on its possible relationship to artiodactyls. Given its substantial body mass, Andrewsarchus was likely not built for sustained high-speed pursuit but instead may have relied on ambush tactics or simply overwhelming smaller prey with its size and power. Its relatively short, muscular limbs would have provided stability and strength rather than speed or agility. Like many large predators, Andrewsarchus probably conserved energy when possible, moving deliberately through its territory and covering considerable distances in search of food opportunities rather than engaging in energetically costly chases.

Social Structure: Lone Hunter or Pack Animal?

The social behavior of Andrewsarchus remains entirely speculative due to the lack of multiple specimens found together or any preserved evidence of social interactions. Some paleontologists suggest that, like many modern large predators such as tigers and bears, Andrewsarchus may have been primarily solitary, maintaining large individual territories and coming together only for mating. Others propose that, given its possible relationship to artiodactyls like hippos and pigs, which often demonstrate complex social behaviors, Andrewsarchus might have lived in small family groups or loose associations. The creature’s large size and presumed metabolic requirements suggest it would have needed substantial hunting territories if carnivorous, potentially favoring a solitary lifestyle. However, if Andrewsarchus was more of an omnivore or scavenger than an active predator, social living might have been more energetically feasible. Until more fossils are discovered, particularly in assemblages suggesting group living, the social structure of Andrewsarchus will remain one of the many mysteries surrounding this enigmatic prehistoric giant.

Significance in Evolution: Andrewsarchus’s Place in Mammalian History

Andrewsarchus occupies a fascinating position in mammalian evolutionary history, representing a time when mammals were experimenting with various ecological niches following the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs. If current classifications linking it to artiodactyls are correct, Andrewsarchus provides an extraordinary example of how dramatically body plans and ecological roles can evolve within a lineage. Its existence demonstrates that the ancestors of today’s hoofed herbivores once included massive predatory forms, highlighting the remarkable plasticity of mammalian evolution. Andrewsarchus lived during a crucial transitional period when modern mammalian groups were becoming established, and ancient groups were beginning their decline. The Middle to Late Eocene epoch witnessed significant global cooling and habitat changes that drove many evolutionary adaptations and extinctions. Understanding Andrewsarchus’s true relationship to other mammals could help clarify important evolutionary transitions, particularly the early radiation of artiodactyls that eventually gave rise to such diverse creatures as giraffes, hippos, and whales.

Extinction Theories: Why Did Andrewsarchus Disappear?

The extinction of Andrewsarchus, like many aspects of its biology, remains speculative due to limited fossil evidence. Most researchers place its disappearance within the broader context of Eocene-Oligocene extinction events, particularly the “Grande Coupure” or “Great Break” around 33.9 million years ago. This period marked a significant cooling of global climates, leading to the expansion of grasslands and the expansion of forests worldwide. Such habitat transformation likely affected the prey base and ecological niche that Andrewsarchus exploited. Additionally, the evolution of more specialized carnivorous mammals, including early representatives of today’s carnivore groups (Carnivora), may have created competition that Andrewsarchus couldn’t overcome. Its specialized feeding apparatus may have become a liability as environments changed. Large-bodied predators are particularly vulnerable to ecosystem disruptions due to their low population densities and high energy requirements, factors that might have contributed to Andrewsarchus’s ultimate demise as its preferred habitats and prey species diminished.

Modern Research: New Insights into an Ancient Beast

Despite being known from a single skull, Andrewsarchus continues to be the subject of ongoing scientific investigation using cutting-edge technologies and analytical approaches. Recent studies have employed CT scanning to examine the internal structure of the fossil skull, revealing details about brain size, sensory capabilities, and bite mechanics that weren’t visible to earlier researchers. Comparative genomics of living artiodactyls and other mammals has helped refine our understanding of Andrewsarchus’s possible evolutionary relationships, though without DNA from the creature itself, these remain hypothetical. Improved dating techniques have better placed Andrewsarchus in its temporal context, while advanced paleoenvironmental reconstructions have enhanced our understanding of its habitat. Computer modeling of biomechanics has allowed researchers to estimate Andrewsarchus’s bite force and feeding capabilities with greater precision than ever before. Future research directions might include renewed expeditions to the fossil-bearing strata of Mongolia in search of additional specimens, particularly post-cranial elements that would resolve many outstanding questions about this remarkable animal’s anatomy and lifestyle.

Cultural Impact: Andrewsarchus in Popular Science and Media

Despite its obscurity compared to dinosaurs and Ice Age mammals, Andrewsarchus has captured the imagination of paleontology enthusiasts and has featured in numerous popular science books, television documentaries, and museum exhibitions. Its massive skull on display at the American Museum of Natural History has become an iconic specimen, inspiring generations of visitors. Andrewsarchus gained broader public recognition following its appearance in the BBC’s “Walking with Beasts” documentary series, where it was portrayed as a fierce scavenger capable of driving other predators from their kills. The creature has been featured in various prehistoric-themed video games, toy lines, and educational materials. Its appeal lies partly in its mysterious nature—the combination of impressive size, fearsome appearance, and scientific uncertainty makes Andrewsarchus a perfect canvas for scientific speculation and artistic interpretation. As one of paleontology’s enigmatic “one-hit wonders” (species known from minimal fossil material), Andrewsarchus embodies the detective work inherent in reconstructing prehistoric life and continues to inspire both scientific inquiry and public fascination with the strange creatures that preceded modern mammals.

Conclusion

Andrewsarchus remains one of paleontology’s most tantalizing mysteries—a creature known from a single massive skull that hints at a remarkable predator unlike anything alive today. As science advances, our understanding of this prehistoric giant continues to evolve, shifting from early conceptions of a wolf-like predator to more nuanced views of a possible shoreline omnivore related to the ancestors of today’s hippopotamuses and whales. While much about Andrewsarchus remains speculative, its existence reminds us of the remarkable diversity of mammalian evolution and the strange, magnificent creatures that have walked our planet through deep time. Until new fossils emerge from the ancient sediments of Mongolia or neighboring regions, Andrewsarchus will continue to occupy a special place in paleontology—a testament to how much we can learn from fragmentary evidence and how much remains to be discovered about Earth’s prehistoric past.