The comparison between modern crocodiles and dinosaurs has fascinated scientists and nature enthusiasts for generations. With their armored bodies, powerful jaws, and prehistoric appearance, crocodiles certainly seem like living fossils that could have crawled straight out of the Mesozoic Era. This resemblance has led many to casually refer to crocodiles as “living dinosaurs” or even “budget dinosaurs” – implying they’re somehow lesser versions of their extinct relatives. But is this comparison scientifically accurate? Are today’s crocodiles really just watered-down versions of dinosaurs, or is their evolutionary story more complex and fascinating? Let’s dive into the relationship between these ancient reptiles and explore what science tells us about their connections and differences.

The Evolutionary Timeline: When Dinosaurs and Crocodilians Diverged

Contrary to popular belief, crocodiles are not descended from dinosaurs, nor are they “living dinosaurs” in the strict scientific sense. Both groups belong to the larger classification of archosaurs (“ruling reptiles”), but they represent separate evolutionary branches that diverged approximately 240 million years ago during the Triassic period. This split created two distinct lineages: the Dinosauromorpha (which led to dinosaurs and eventually birds) and the Pseudosuchia (which led to crocodilians). While dinosaurs dominated land environments for around 165 million years before most lineages went extinct 66 million years ago, crocodilians evolved along their own separate path. Modern crocodiles are actually more closely related to the crocodylomorphs that lived alongside dinosaurs than to the dinosaurs themselves, making them cousins rather than descendants of dinosaurs.

Anatomical Similarities: More Than Just Coincidence

Despite their separate evolutionary paths, crocodiles and dinosaurs share several anatomical features that reflect their common archosaur ancestry. Both possess what scientists call the “diapsid skull,” characterized by two openings behind each eye socket that house jaw muscles. They also share similar scale patterns, powerful jaws, and certain tooth structures. The archosaurian ankle joint configuration is another shared trait, allowing for more efficient locomotion than found in other reptiles. These similarities aren’t evidence that crocodiles are dinosaurs, but rather demonstrate that both groups inherited certain features from their common ancestors. Some of these shared traits represent solutions to similar evolutionary pressures, while others are ancestral characteristics that have persisted in crocodilians for over 200 million years—a testament to their evolutionary success rather than evidence they’re somehow “lesser dinosaurs.”

Survival Strategies: Why Crocodiles Endured While Dinosaurs Perished

The survival of crocodilians through the catastrophic end-Cretaceous extinction event that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs represents one of evolution’s most remarkable success stories. Their persistence wasn’t due to being “budget” versions of anything, but rather resulted from specialized adaptations that proved advantageous during global catastrophe. Crocodilians possessed semi-aquatic lifestyles that likely buffered them from the worst immediate effects of the asteroid impact. Their ability to remain submerged for extended periods, slow metabolic rates allowing for long periods without food, and behavioral adaptations like scavenging gave them crucial advantages. Additionally, crocodilians had already evolved physiological mechanisms to handle highly acidic conditions in their bodies during long dives—an adaptation that may have helped them survive acidification events following the impact. Rather than representing evolutionary compromises, these traits showcase specialized adaptations that proved extraordinarily valuable for survival.

Metabolic Differences: Cold-Blooded vs. Warm-Blooded

One fundamental difference between most dinosaurs and modern crocodilians lies in their metabolic strategies. Scientific evidence increasingly suggests that many dinosaurs were endothermic (warm-blooded) or maintained elevated body temperatures through a combination of metabolic and behavioral adaptations. Crocodilians, by contrast, are ectothermic (cold-blooded), relying primarily on external heat sources to regulate their body temperature. This metabolic difference represents divergent evolutionary paths rather than any sort of “budget” compromise. The ectothermic strategy allows crocodilians to survive on far less food than a comparably sized endotherm, enabling them to thrive in environments with unpredictable food availability. A large crocodile can potentially survive for months or even a year without eating—an adaptation that has served the lineage extraordinarily well throughout evolutionary history and during extinction events. This metabolic strategy represents a specialized adaptation rather than an inferior or “budget” version of dinosaurian physiology.

Size Comparisons: Ancient Crocodilians vs. Dinosaurs

While modern crocodiles may seem modest compared to the largest dinosaurs, ancient crocodilians included some truly massive species that rivaled dinosaurs in size and predatory capability. Sarcosuchus imperator, often called “SuperCroc,” reached estimated lengths of 39-40 feet (12 meters) and weighed approximately 8 tons—larger than many predatory dinosaurs. Deinosuchus, another prehistoric crocodilian that lived during the Late Cretaceous, grew to lengths of about 33-35 feet (10-10.6 meters) and likely preyed upon dinosaurs. Purussaurus from the Miocene epoch could reach lengths of 41 feet (12.5 meters) with massive skulls nearly 5 feet long. These examples demonstrate that the crocodilian evolutionary path produced apex predators that were hardly “budget” versions of anything. The slightly smaller size of modern crocodilians compared to these giants reflects more recent evolutionary pressures and ecological niches rather than any inherent limitation of the crocodilian body plan.

Ecological Roles: Specialized Predators, Not Lesser Dinosaurs

Modern crocodilians occupy specialized ecological niches as semi-aquatic ambush predators—roles that are fundamentally different from those filled by most dinosaurs. Saltwater crocodiles, for instance, are supremely adapted apex predators capable of taking down virtually any animal that enters their territory, including large mammals. Their bite force, measured at up to 3,700 pounds per square inch (psi), exceeds that of any living animal and rivals or surpasses estimates for large theropod dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex. American alligators function as ecosystem engineers, creating and maintaining “alligator holes” that provide crucial water sources for countless other species during dry periods. Gharials have evolved specialized fish-catching snouts that represent extreme specialization. These ecological roles don’t represent “budget” versions of dinosaurian niches but rather showcase the unique evolutionary path crocodilians have taken—one that has proven remarkably successful across hundreds of millions of years.

Evolutionary Conservatism: Why Change a Winning Formula?

The basic crocodilian body plan has remained relatively unchanged for over 80 million years, leading some to mistakenly view them as “primitive” or “living fossils.” However, evolutionary biologists recognize this stability not as evidence of inferiority but as a testament to the effectiveness of their adaptations. When an organism is exceptionally well-adapted to its ecological niche, natural selection tends to maintain those successful traits rather than drastically altering them—a phenomenon called evolutionary stasis or conservatism. Modern crocodilians have certainly continued to evolve at the genetic and physiological levels, but their fundamental body plan has proven so effective for their semi-aquatic predatory lifestyle that major morphological changes haven’t been necessary. This evolutionary conservatism represents success rather than stagnation or any sense of being a “budget” version of another taxon. Their persistence across multiple mass extinction events further validates the effectiveness of their evolutionary strategy.

Birds: The True Living Dinosaurs

If we’re looking for “living dinosaurs” in the modern world, we should direct our attention not to crocodiles but to birds. Modern birds are not just related to dinosaurs—they are, in the strictest cladistic sense, actual dinosaurs, having evolved directly from small theropod dinosaurs during the Jurassic period. The evidence for this relationship is overwhelming, including hundreds of shared anatomical features, behavioral similarities, and the presence of feathers in many non-avian dinosaur fossils. The evolutionary transition from non-avian dinosaurs to birds is one of the most well-documented evolutionary sequences in the fossil record, with remarkable transitional fossils like Archaeopteryx, Microraptor, and many others. So while crocodilians evolved alongside dinosaurs as a separate branch of archosaurs, birds represent the surviving dinosaur lineage. Rather than thinking of crocodiles as “budget dinosaurs,” it would be more accurate to recognize the sparrow outside your window as a living representative of the dinosaur lineage.

Advanced Sensory Systems: Specialized, Not Simplified

Modern crocodilians possess remarkably sophisticated sensory adaptations that are far from “budget” versions of dinosaurian capabilities. They feature specialized pressure receptors called dome pressure receptors (DPRs) distributed across their faces that can detect minute pressure changes in water, allowing them to locate prey even in complete darkness. Crocodilian eyes contain a tapetum lucidum that enhances night vision, specialized color vision, and protective third eyelids (nictitating membranes). Their ears are highly adapted for detecting both airborne and underwater sounds, with specialized valves that close when submerged. Perhaps most impressive are integumentary sense organs (ISOs) that cover their skin, particularly concentrated around their jaws. These specialized receptors are so sensitive they can detect a single drop of water rippling the surface from meters away. These sophisticated sensory adaptations represent specialized evolutionary developments rather than simplified or “budget” versions of dinosaurian capabilities—they’re precisely calibrated for the crocodilian semi-aquatic hunting strategy.

Parental Care: Sophisticated Behaviors Shared with Dinosaurs

One fascinating area where crocodilians and dinosaurs show intriguing parallels is in their parental care behaviors. Crocodilians display remarkably sophisticated parental care, with mothers guarding their nests vigilantly during incubation, responding to the calls of hatchlings by helping them emerge from their eggs, and carrying newly hatched young in their mouths to water. Many species continue protecting their young for months or even years after hatching. These behaviors closely resemble parental care strategies inferred for many dinosaur species based on fossil evidence, including nest guarding and potential extended care of young. This similarity likely reflects the common archosaurian heritage of both groups, as advanced parental care was probably present in their shared ancestors. Far from representing a “budget” version of dinosaurian behavior, crocodilian parental care demonstrates sophisticated social behaviors that have proven highly adaptive and successful across millions of years of evolution.

Intelligence and Learning: Smarter Than You Might Think

Crocodilians display surprising cognitive abilities that challenge any notion of them being “budget” versions of dinosaurs or primitive reptiles. Research has documented their capacity for complex learning, tool use, cooperative hunting, and long-term memory. Studies have shown that crocodilians can learn to respond to specific sound frequencies, recognize individual humans, and remember training cues for years. Some species have been observed using sticks as lures to attract nesting birds—placing the sticks on their snouts during bird nesting seasons when birds collect materials, then snapping up birds that approach to take the sticks. American alligators and mugger crocodiles have been documented engaging in coordinated group hunting behaviors. While dinosaur intelligence is difficult to assess directly, brain endocast studies suggest varying levels of cognitive ability among dinosaur species. The sophisticated learning abilities of crocodilians likely evolved independently along their separate evolutionary branch, representing specialized adaptations rather than simplified dinosaurian traits.

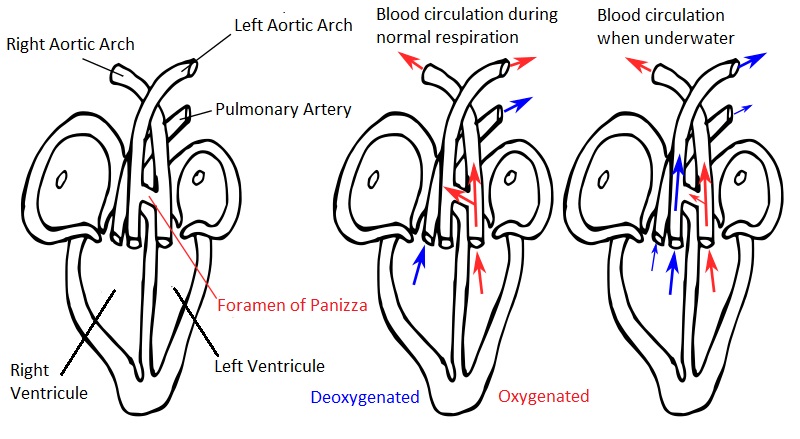

Cardiovascular Sophistication: Advanced Biological Engineering

Crocodilian cardiovascular systems display remarkable adaptations that far surpass the “budget” label some might apply to these animals. Unlike most reptiles, crocodilians possess a four-chambered heart similar to mammals and birds (including dinosaurs), but with a crucial difference: they can bypass this system when needed. Through a specialized valve called the foramen of Panizza, crocodilians can shunt blood away from their lungs during extended dives, effectively switching between completely separated circulation (like mammals and birds) and partially separated circulation (like other reptiles). This physiological flexibility represents an adaptive advantage rather than an evolutionary compromise. Crocodilians also possess a hepatic piston breathing mechanism that allows them to breathe while most of their body remains submerged—a sophisticated adaptation for their semi-aquatic lifestyle. These cardiovascular specializations demonstrate that crocodilian physiology represents a highly refined system for their specific ecological niche rather than a simplified version of dinosaurian physiology.

The Verdict: Evolutionary Cousins, Not Budget Versions

The framing of crocodiles as “budget dinosaurs” fundamentally misunderstands both evolutionary relationships and the nature of adaptation. Crocodilians aren’t simplified or less-evolved versions of dinosaurs—they represent a separate, highly successful branch of archosaurs that followed their own evolutionary path. Their body plan, physiology, and behaviors aren’t compromised or inferior versions of dinosaurian traits, but rather specialized adaptations perfectly suited to their semi-aquatic predatory lifestyle. The remarkable 200+ million year success story of crocodilians, surviving multiple mass extinction events including the one that eliminated non-avian dinosaurs, testifies to the effectiveness of their evolutionary strategy. If anything, their persistence while most dinosaur lineages perished might suggest their adaptations were more versatile and resilient in certain contexts. Modern crocodilians represent the culmination of a distinct and incredibly successful evolutionary lineage that deserves appreciation on its own terms, not as a comparison to their distant archosaur cousins.

In conclusion, crocodiles are not “budget dinosaurs” but rather represent one of Earth’s most successful evolutionary experiments—a lineage that has maintained its ecological dominance for over 200 million years through specialized adaptations perfectly suited to their environment. While dinosaurs and crocodilians share a common ancestry as archosaurs, they followed separate evolutionary paths, each developing unique specializations. The proper comparison isn’t that crocodiles are lesser dinosaurs, but that both groups exemplify the incredible diversity and adaptability of the archosaur lineage. Modern birds, not crocodiles, are the true living dinosaurs among us. Rather than viewing crocodilians through the lens of what they’re not, we should appreciate them for what they are: evolutionary masterpieces whose design has stood the ultimate test—time.